Eleventh Circuit ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

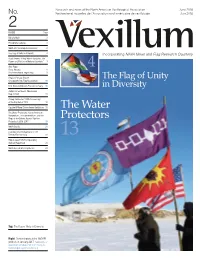

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Union of South Africa

ECUADOR Flag Description: three horizontal bands of yellow (top, double width), blue, and red with the coat of arms superimposed at the center of the flag; similar to the flag of Colombia, which is shorter and does not bear a coat of arms. Background. The "Republic of the Equator" was one of three countries that emerged from the collapse of Gran Colombia in 1830 (the others are Colombia and Venezuela). Between 1904 and 1942, Ecuador lost territories in a series of conflicts with its neighbors. A border war with Peru that flared in 1995 was resolved in 1999. Although Ecuador marked 25 years of civilian governance in 2004, the period has been marked by political instability. Seven presidents have governed Ecuador since 1996. Geography Ecuador. Location: Western South America, bordering the Pacific Ocean at the Equator, between Colombia and Peru. Area: total: 283,560 sq km. Area - comparative: slightly smaller than Nevada. Land boundaries: total: 2,010 km. Border countries: Colombia 590 km, Peru 1,420 km. Coastline: 2,237 km. Climate: tropical along coast, becoming cooler inland at higher elevations; tropical in Amazo- nian jungle lowlands. Terrain: coastal plain (costa), inter-Andean central highlands (sierra), and flat to rolling eastern jungle (oriente). Natural resources: petroleum, fish, timber, hydropower. Natural hazards: frequent earthquakes, landslides, volcanic activity; floods; periodic droughts. Military: Army, Navy (includes Naval Infantry, Naval Aviation, Coast Guard), Air Force (Fuerza Aerea Ecuatoriana, FAE) (2007) (Source CIA Fact Book 2006) 1943 Veh, Recce. M3A1 Scout Car. 1990 Carr, Pers, Armd, 4x4. UNIMOG UR-416. Remarks: Between 1943 and 1946, the US de- Remarks: As of 1990 Ecuador was reported by livered 12 M3A1s to Ecuador as part of the the UN to have 10 UR-416s in service. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

World Map Flag of Ecuador

From North to South World map 2007/7/22 Flag of Ecuador Ecuador’s flag 2007/7/22 1 Scene in the highway Ecuador in general 2007/7/22 Houses in the field 2007/7/22 2 Full Load? 2007/7/22 Friut stand 2007/7/22 3 Clothes washing 2007/7/22 Street in Quito Street in Quito 2007/7/22 4 Catholic church Catholic church 2007/7/22 Catholic church 2007/7/22 5 The true Equator line? The Equator Monument 2007/7/22 The Equator The Middle of the World 2007/7/22 6 North or South? Clockwise or anticlockwise? 2007/7/22 The burial The burial 2007/7/22 7 The Sierra Scene from the Sierra 2007/7/22 The corn field The corn field 2007/7/22 8 A process of yucca drink A yucca drink 2007/7/22 The local huts A native hut 2007/7/22 9 Seeking for gold Find any gold? 2007/7/22 Flowers in the jungle Flowers in the jungle 2007/7/22 10 2007/7/22 2007/7/22 11 Trees in the jungle 2007/7/22 2007/7/22 12 The waterfall 2007/7/22 Making candies Candies man? 2007/7/22 13 One kind of a tour bus Tour bus 2007/7/22 The market place 2007/7/22 14 Meet with the natives The country side 2007/7/22 In Machala 2007/7/22 15 In Guayaquil 2007/7/22 Imports Their business 2007/7/22 16 2007/7/22 Bike shops 2007/7/22 17 Hardware stores 2007/7/22 Farms 2007/7/22 18 Gas stations 2007/7/22 The Chinese ministry: Iquique, Chile 2007/7/22 19 2007/7/22 The Chinese ministry: Guayaquil,Ecuador 2007/7/22 20 2007/7/22 2007/7/22 21 2007/7/22 2007/7/22 22 2007/7/22 2007/7/22 23 Quevedor Quevedo, Ecuador 2007/7/22 2007/7/22 24 Machala Machala, Ecuador 2007/7/22 2007/7/22 25 TheThe lost sheepChinese-The lost -

Magical Realism and Latin America Maria Eugenia B

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2003 Magical Realism and Latin America Maria Eugenia B. Rave Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Latin American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rave, Maria Eugenia B., "Magical Realism and Latin America" (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 481. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/481 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. MAGICAL REALISM AND LATIN AMERICA BY Maria Eugenia B. Rave A.S. University of Maine, 1991 B.A. University of Maine, 1995 B.S. University of Maine, 1995 A MASTER PROJECT Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2003 Advisory Committee: Kathleen March, Professor of Spanish, Advisor Michael H. Lewis, Professor of Art James Troiano, Professor of Spanish Owen F. Smith, Associate Professor of Art Copyright 2003 Maria Eugenia Rave MAGICAL REALISM AND LATIN AMERICA By Maria Eugenia Rave Master Project Advisor: Professor Kathleen March An Abstract of the Master Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) May, 2003 This work is an attempt to present a brief and simple view, both written and illustrated, concerning the controversial concept of Magical Realism for non-specialists. This study analyzes Magical Realism as a form of literary expression and artistic style by some Latin American authors and two artists. -

Colombia, Latin America

Colombia, Latin America The flag of Colombia was officially adopted on November 26, 1861. The yellow band takes up half the flag and signifies the gold found in the Colombian land. The blue stripe represents the seas off its shores and red stands for the blood spilled on the battlegrounds for freedom. Other interpretations of the colors include the sovereignty and justice (yellow), loyalty and vigilance (blue) and valor and generosity (red). Colombia is located near the equator. Therefore, the majority of the time the weather is very hot. The climate is tropical and it is humid along the coast and WEATHER eastern plains. In the highlands of the Andes Mountains it’s significantly cooler. Colombia has five natural regions, each region usually maintains a constant temperature throughout the year. LIFESPAN Life expectancy on average is 75 years old (males 71 years, females 78 years). Despite a serious armed conflict, Colombia has experienced positive growth over the past several years. However, high unemployment is a major concern ECONOMY and is contributing to extreme inequality in the income distribution of the population. Over 45% of the population is below the poverty line. RELIGION Catholic 90% and others 10%. The educational experience of many Colombian children begins with preschool academy until the age of 5. Basic education is compulsory and has two stages (primary and secondary). In many rural areas teachers are poorly qualified and only five years of primary schooling are offered. Basic education is followed by SCHOOLING Middle vocational education. After the successful completion of all the basic and middle education years, a high-school diploma is awarded. -

Let the Water Run

University: University of Twente Host organization: Neverland Organic Farm Supervisor: Joy Clancy Mentor: Tina Marshall September – December 2012 Let the water run Design and implementation of a micro hydropower project in Tumianuma, Chirusco valley, Ecuador Annegreet Ottow-Boekeloo Student number: s0176311 Study: Sustainable Energy Technology Faculty: CTW Research group: CSTM Preface Around the world many people live in areas where streams and rivers are located. Water is an important source of life, what everyone will agree. Also in the Chirusco valley in Ecuador water is highly valued. Even though there is a lot of water available, no water can be spoiled. This mindset is already there from way before the Inca’s, where the indigenous people valued water as the most important source of life. Besides using the water for drinking, the force of the water can be used. Streams and rivers are potential sources of energy for lighting, communication and processes industries. This natural resource can be exploited by the building of small hydro-power schemes. The water in the river will be borrowed and not be consumed. The force of the water can make a turbine run which can be transferred to the generator that will convert it into electricity. And then you will have a green source of energy. The Neverland farm, located in Tumianuma in the Chirusco valley, started building such a micro-hydro scheme three years ago. By the time I came to work on this project they got new funds and new hope to finally finish this project. Being a student from Sustainable Energy Technology, University of Twente, I was highly interested in renewable energies and especially the application in rural areas. -

Post-Colonial Relationships on the Flagpole

Middle States Geographer, 2018, 51: 77-86 IMPERIAL BANNERS? POST-COLONIAL RELATIONSHIPS ON THE FLAGPOLE Noah Anders Carlen Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering United States Military Academy West Point, NY 10997 ABSTRACT: This research was conducted to examine trends in the flags of post-colonial nations around the world, grouping them by the empire to which they belonged. A flag is the preeminent symbol of a nation, typically representing a country’s most important values. As empires broke up, dozens of new countries struggled to find and establish common identities. As expected, countries that went through similar colonial experiences produced flags with similar values, reflecting their history with imperialism. This research compiled data of what was represented on the national flag of every former colonial country and tallied how many from each empire (Portuguese, Spanish, French, and British) included certain values or ideas. The resulting information showed that the institution of independence was much more prominent in Portuguese and Spanish countries than it was in French and British countries, caused by greater struggles during their colonial period. This project reveals how flags can be used collectively as a powerful tool to analyze geographic and historical trends, using national symbols as a point of comparison between countries across the globe. Keywords: Flags, vexillology, colonialism, identity INTRODUCTION Flags are strongly connected to the concepts of patriotism and national identity, and as such they reveal a lot about who they represent. Like any symbol, they are dynamic over time, depicting only a snippet of a people’s values and how they define their country. -

Geography and Vexillology: Landscapes in the Flags

Geography and vexillology: landscapes in flags By Tiago José Berg Abstract This paper aims to present how the national flags have on its symbo - lism a representation of landscape. In geography, both in academic levels as well as in school teaching, landscape takes on a central theme that has so far been the subject of scientific debate of great importance by geographers as a way of seeing the world and a form of representing a specific surface of the Earth. In vexillology, the symbolism of the modern nation-state has developed a number of examples where the arrangement of stripes (or even the coat of arms) of some national flags bring certain aspects that are not immediately apparent, but they may become beautiful examples of a stylized representation of the landscape. Therefore, in this paper we seek a dialogue between geography and vexillology, showing how the representation of landscape in the flags can become a relevant theme to be used in academic research and a fascinating resource to enrich the teaching in schools. Introduction The last decades of the twentieth century saw the revival of interest in studies of the landscape geographers, both the number of publications, the associations made with the theme. The landscape, rather than a return to “classical geography” or even the new perspectives presented by the cultural geography, back to being inserted in geographical studies with a different approach. Both in academic level as well as in school education, the landscape takes on a theme that has been the subject of scien - tific debate of great importance by geographers as a way of seeing the world and a way of representing the specific surface of the Earth. -

Ecuador by Ben and Tam Flag of Ecuador Red Stands for the Blood Shed, by the Soldiers and Martyrs of the Independence Battles

Ecuador By Ben and Tam Flag of Ecuador Red stands for the blood shed, by the soldiers and martyrs of the independence battles. Blue represents the colour of the sea and sky. Yellow symbolize the abundance and fertility of the crops and land. Capital City Quito, capital of Ecuador, is located on a horizontal strip of land which extends from North to South. It is an enclave between beautiful mountains, which combined with the warmth of their people, their attractive squares, streets, parks and historical monuments, make it one unique and unforgettable place. Borders around Ecuador Ecuador is a republic in north western South America, bordered by the Pacific Ocean in west, by Colombia in north and by Peru in south east and south and it shares maritime borders with Costa Rica. Sea and Oceans around Ecuador Ecuador is around at the Pacific ocean and Atlantic Ocean Largest city Guayaquil is the largest and most populous city in Ecuador, with around 21.69 million people. Main rivers of Ecuador Almost all of the rivers in Ecuador rise in the Sierra region and flow east toward the Amazon River or west toward the Pacific Ocean. Major rivers include: Pastaza River Napo River Putumayo River. Religion Ecuador Religion. The main Ecuador religion is Roman Catholicism, as is true throughout much of Latin America. Over 90% of Ecuadorians are Catholic. The church is a predominate feature of just about any town square in Ecuador. Their Catholic faith has been mixed with the beliefs of the indigenous people. Facts about Ecuador Ecuador was colonized by the Spanish in 1563. -

Universidad Nacional De Chimborazo Facultad De

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE CHIMBORAZO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN, HUMANAS Y TECNOLOGÍAS CARRERA DE IDIOMAS Research work previous obtaining the professional degree as: “Licenciada en Ciencias de la Educación, profesora de Idiomas; Inglés” TEMA: ―Aplicación de técnicas de enseñanza para el aprendizaje de la destreza oral en los niños del Primer Año de Educación General Básica, de la Escuela de Educación Básica Fiscomisional ‗Dr. Gabriel García Moreno‘ del Cantón Guano, Provincia de Chimborazo; durante el año lectivo 2013-2014‖. AUTHORS: Vargas Vimos Amparo Isabel Shiguango Calapucha Bexy Diana TUTOR: Ing. Luis Machado Riobamba - Ecuador 2014 I UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE CHIMBORAZO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN, HUMANAS Y TECNOLOGÍAS CARRERA DE IDIOMAS Research work previous to obtain the professional degree as: “Licenciada en Ciencias de la Educación, profesora de Idiomas; Inglés” THEME: ―Application of teaching techniques to develop the oral skill in the students of Primer Año de Educación General Básica, at Escuela de Educación Básica Fiscomisional ‗Dr. Gabriel García Moreno‘, Guano canton, Chimborazo province; during the school year 2013-2014‖. II CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINALITY We hereby declare that the thesis entitled ―Application of teaching techniques to develop the oral skill in the students of Primer Año de Educación Básica, at Escuela de Educación Básica Fiscomisional ‗Dr. Gabriel García Moreno‘, Guano canton, Chimborazo province, durin ig the school year 2013-2014‖ is our own work and to the best of our knowledge. We also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of our own work, except to the contributions of other authors which are correctly cited. -

This Is the Project Gutenberg Etext of the CIA World Factbook* *****This File Should Be Named World12.Txt Or World12.Zip******

*This is the Project Gutenberg Etext of The CIA World Factbook* *****This file should be named world12.txt or world12.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, xxxxx11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, xxxxx10a.txt. Information about Project Gutenberg (one page) We produce about one million dollars for each hour we work. One hundred hours is a conservative estimate for how long it we take to get any etext selected, entered, proofread, edited, copyright searched and analyzed, the copyright letters written, etc. This projected audience is one hundred million readers. If our value per text is nominally estimated at one dollar, then we produce a million dollars per hour; next year we will have to do four text files per month, thus upping our productivity to two million/hr. The Goal of Project Gutenberg is to Give Away One Trillion Etext Files by the December 31, 2001. [10,000 x 100,000,000=Trillion] This is ten thousand titles each to one hundred million readers. We need your donations more than ever! All donations should be made to "Project Gutenberg/IBC", and are tax deductible to the extent allowable by law ("IBC" is Illinois Benedictine College). (Subscriptions to our paper newsletter go to IBC, too) Send to: David Turner, Project Gutenberg Illinois Benedictine College 5700 College Road Lisle, IL 60532-0900 All communication to Project Gutenberg should be carried out via Illinois Benedictine College unless via email. This is for help in keeping me from being swept under by paper mail as follows: 1.