The Eastern Asian–Eastern North American Floristic Disjunction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Fern Journal

AMERICAN FERN JOURNAL QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN FERN SOCIETY Broad-Scale Integrity and Local Divergence in the Fiddlehead Fern Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Todaro (Onocleaceae) DANIEL M. KOENEMANN Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, CA 91711-3157, e-mail: [email protected] JACQUELINE A. MAISONPIERRE University of Vermont, Department of Plant Biology, Jeffords Hall, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, e-mail: [email protected] DAVID S. BARRINGTON University of Vermont, Department of Plant Biology, Jeffords Hall, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, e-mail: [email protected] American Fern Journal 101(4):213–230 (2011) Broad-Scale Integrity and Local Divergence in the Fiddlehead Fern Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Todaro (Onocleaceae) DANIEL M. KOENEMANN Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, CA 91711-3157, e-mail: [email protected] JACQUELINE A. MAISONPIERRE University of Vermont, Department of Plant Biology, Jeffords Hall, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, e-mail: [email protected] DAVID S. BARRINGTON University of Vermont, Department of Plant Biology, Jeffords Hall, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—Matteuccia struthiopteris (Onocleaceae) has a present-day distribution across much of the north-temperate and boreal regions of the world. Much of its current North American and European distribution was covered in ice or uninhabitable tundra during the Pleistocene. Here we use DNA sequences and AFLP data to investigate the genetic variation of the fiddlehead fern at two geographic scales to infer the historical biogeography of the species. Matteuccia struthiopteris segregates globally into minimally divergent (0.3%) Eurasian and American lineages. -

Palaeogeograph Y, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology , 17(1975): 157--172 © Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam -- Printed in the Netherlands

Palaeogeograph y, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology , 17(1975): 157--172 © Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam -- Printed in The Netherlands CLIMATIC CHANGES IN EASTERN ASIA AS INDICATED BY FOSSIL FLORAS. II. LATE CRETACEOUS AND DANIAN V. A. KRASSILOV Institute of Biology and Pedology, Far-Eastern Scientific Centre, U.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok (U.S.S.R.) (Received June 17, 1974; accepted for publication November 11, 1974) ABSTRACT Krassilov, V. A., 1975. Climatic changes in Eastern Asia as indicated by fossil floras. II. Late Cretaceous and Danian. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol., 17:157--172. Four Late Cretaceous phytoclimatic zones -- subtropical, warm--temperate, temperate and boreal -- are recognized in the Northern Hemisphere. Warm--temperate vegetation terminates at North Sakhalin and Vancouver Island. Floras of various phytoclimatic zones display parallel evolution in response to climatic changes, i.e., a temperature rise up to the Campanian interrupted by minor Coniacian cooling, and subsequent deterioration of cli- mate culminating in the Late Danian. Cooling episodes were accompanied by expansions of dicotyledons with platanoid leaves, whereas the entire-margined leaf proportion increased during climatic optima. The floristic succession was also influenced by tectonic events, such as orogenic and volcanic activity which commenced in Late Cenomanian--Turonian times. Major replacements of ecological dominants occurred at the Maastrichtian/Danian and Early/Late Danian boundaries. INTRODUCTION The principal approaches to the climatic interpretation of fossil floras have been outlined in my preceding paper (Krassilov, 1973a). So far as Late Creta- ceous floras are concerned, extrapolation (i.e. inferences from tolerance ranges of allied modern taxa) is gaining in importance and the entire/non-entire leaf type ratio is no less expressive than it is in Tertiary floras. -

(Polypodiales) Plastomes Reveals Two Hypervariable Regions Maria D

Logacheva et al. BMC Plant Biology 2017, 17(Suppl 2):255 DOI 10.1186/s12870-017-1195-z RESEARCH Open Access Comparative analysis of inverted repeats of polypod fern (Polypodiales) plastomes reveals two hypervariable regions Maria D. Logacheva1, Anastasiya A. Krinitsina1, Maxim S. Belenikin1,2, Kamil Khafizov2,3, Evgenii A. Konorov1,4, Sergey V. Kuptsov1 and Anna S. Speranskaya1,3* From Belyaev Conference Novosibirsk, Russia. 07-10 August 2017 Abstract Background: Ferns are large and underexplored group of vascular plants (~ 11 thousands species). The genomic data available by now include low coverage nuclear genomes sequences and partial sequences of mitochondrial genomes for six species and several plastid genomes. Results: We characterized plastid genomes of three species of Dryopteris, which is one of the largest fern genera, using sequencing of chloroplast DNA enriched samples and performed comparative analysis with available plastomes of Polypodiales, the most species-rich group of ferns. We also sequenced the plastome of Adianthum hispidulum (Pteridaceae). Unexpectedly, we found high variability in the IR region, including duplication of rrn16 in D. blanfordii, complete loss of trnI-GAU in D. filix-mas, its pseudogenization due to the loss of an exon in D. blanfordii. Analysis of previously reported plastomes of Polypodiales demonstrated that Woodwardia unigemmata and Lepisorus clathratus have unusual insertions in the IR region. The sequence of these inserted regions has high similarity to several LSC fragments of ferns outside of Polypodiales and to spacer between tRNA-CGA and tRNA-TTT genes of mitochondrial genome of Asplenium nidus. We suggest that this reflects the ancient DNA transfer from mitochondrial to plastid genome occurred in a common ancestor of ferns. -

Flora of New Zealand Ferns and Lycophytes Onocleaceae Pj Brownsey

FLORA OF NEW ZEALAND FERNS AND LYCOPHYTES ONOCLEACEAE P.J. BROWNSEY & L.R. PERRIE Fascicle 28 – DECEMBER 2020 © Landcare Research New Zealand Limited 2020. Unless indicated otherwise for specific items, this copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence Attribution if redistributing to the public without adaptation: "Source: Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research" Attribution if making an adaptation or derivative work: "Sourced from Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research" See Image Information for copyright and licence details for images. CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Brownsey, P. J. (Patrick John), 1948– Flora of New Zealand : ferns and lycophytes. Fascicle 28, Onocleaceae / P.J. Brownsey and L.R. Perrie. -- Lincoln, N.Z.: Manaaki Whenua Press, 2020. 1 online resource ISBN 978-0-947525-68-2 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-478-34761-6 (set) 1.Ferns -- New Zealand – Identification. I. Perrie, L. R. (Leon Richard). II. Title. III. Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd. UDC 582.394.742(931) DC 587.30993 DOI: 10.7931/rjn3-hp32 This work should be cited as: Brownsey, P.J. & Perrie, L.R. 2020: Onocleaceae. In: Breitwieser, I. (ed.) Flora of New Zealand — Ferns and Lycophytes. Fascicle 28. Manaaki Whenua Press, Lincoln. http://dx.doi.org/10.7931/rjn3-hp32 Date submitted: 18 Jun 2020; Date accepted: 21 Jul 2020; Date published: 2 January 2021 Cover image: Onoclea sensibilis. Herbarium specimen of cultivated plant from near Swanson, Auckland. CHR 229544. Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................................................1 -

A Molecular Phylogeny with Morphological Implications and Infrageneric Taxonomy

TAXON 62 (3) • June 2013: 441–457 Wei & al. • Phylogeny and classification of Diplazium SYSTEMATICS AND PHYLOGENY Toward a new circumscription of the twinsorus-fern genus Diplazium (Athyriaceae): A molecular phylogeny with morphological implications and infrageneric taxonomy Ran Wei,1,2 Harald Schneider1,3 & Xian-Chun Zhang1 1 State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, The Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, P.R. China 2 University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, P.R. China 3 Department of Botany, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, U.K. Author for correspondence: Xian-Chun Zhang, [email protected] Abstract Diplazium and allied segregates (Allantodia, Callipteris, Monomelangium) represent highly diverse genera belong- ing to the lady-fern family Athyriaceae. Because of the morphological diversity and lack of molecular phylogenetic analyses of this group of ferns, generic circumscription and infrageneric relationships within it are poorly understood. In the present study, the phylogenetic relationships of these genera were investigated using a comprehensive taxonomic sampling including 89 species representing all formerly accepted segregates. For each species, we sampled over 6000 DNA nucleotides of up to seven plastid genomic regions: atpA, atpB, matK, rbcL, rps4, rps4-trnS IGS, and trnL intron plus trnL-trnF IGS. Phylogenetic analyses including maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods congruently resolved Allantodia, Cal- lipteris and Monomelangium nested within Diplazium; therefore a large genus concept of Diplazium is accepted to keep this group of ferns monophyletic and to avoid paraphyletic or polyphyletic taxa. Four well-supported clades and eight robust sub- clades were found in the phylogenetic topology. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

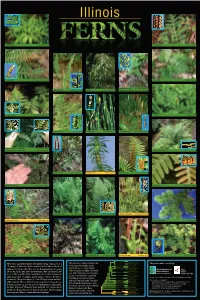

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

A Revised Family-Level Classification for Eupolypod II Ferns (Polypodiidae: Polypodiales)

TAXON 61 (3) • June 2012: 515–533 Rothfels & al. • Eupolypod II classification A revised family-level classification for eupolypod II ferns (Polypodiidae: Polypodiales) Carl J. Rothfels,1 Michael A. Sundue,2 Li-Yaung Kuo,3 Anders Larsson,4 Masahiro Kato,5 Eric Schuettpelz6 & Kathleen M. Pryer1 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, Box 90338, Durham, North Carolina 27708, U.S.A. 2 The Pringle Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology, University of Vermont, 27 Colchester Ave., Burlington, Vermont 05405, U.S.A. 3 Institute of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei, 10617, Taiwan 4 Systematic Biology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyv. 18D, 752 36, Uppsala, Sweden 5 Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science, Tsukuba 305-0005, Japan 6 Department of Biology and Marine Biology, University of North Carolina Wilmington, 601 South College Road, Wilmington, North Carolina 28403, U.S.A. Carl J. Rothfels and Michael A. Sundue contributed equally to this work. Author for correspondence: Carl J. Rothfels, [email protected] Abstract We present a family-level classification for the eupolypod II clade of leptosporangiate ferns, one of the two major lineages within the Eupolypods, and one of the few parts of the fern tree of life where family-level relationships were not well understood at the time of publication of the 2006 fern classification by Smith & al. Comprising over 2500 species, the composition and particularly the relationships among the major clades of this group have historically been contentious and defied phylogenetic resolution until very recently. Our classification reflects the most current available data, largely derived from published molecular phylogenetic studies. -

Fern Gazette

FERN GAZ. 17(5): 279-286. 2006 279 FILICALEAN FERNS FROM THE TERTIARY OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA: OSMUNDA L. (OSMUNDACEAE : PTERIDOPHYTA), WOODWARDIA SM. (BLECHNACEAE : PTERIDOPHYTA) AND ONOCLEOID FORMS (FILICALES : PTERIDOPHYTA) K.B. PIGG1, M.L. DEVORE2 & W.C. WEHR3† 1School of Life Sciences, PO Box 874501, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-4501, USA; 2Department of Biological & Environmental Sciences, 135 Herty Hall, Georgia College & State University, Milledgeville, GA 31061, USA; 3Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, PO Box 353010, Seattle, WA 98195-3010, USA †deceased, 12 April, 2004 Key words: Blechnaceae, fossil fern, Osmunda, Osmundaceae, Tertiary, wessiea, woodwardia ABSTRACT Recently discovered frond remains assignable to Osmunda wehrii Miller (Osmundaceae), as well as several new records of woodwardia (Blechnaceae), and a new onocleoid fern are reported from the Tertiary of western North America. Pinnule morphology of O. wehrii supports the inclusion of this species in Osmunda subgenus Osmunda, as originally proposed by Miller and suggests a close affinity to O. regalis L. and O. japonica Thunb. New occurrences of the woodwardia aerolata clade are noted for the Late Paleocene of western North Dakota and of a highly reticulate-veined form from the Miocene of western Washington. Re-evaluation of specimens of w. deflexipinna H. Smith (Succor Creek, Miocene) confirms its close affinity to w. virginica J. Smith. A fern with onocleoid anatomy is recognized from the middle Eocene Clarno Nut Beds of Oregon. Together, these examples demonstrate that the presence of critical taxonomic features, even in fragmentary remains, can increase our knowledge of filicalean fern evolution, biogeography and ecology in the Tertiary. -

The Marattiales and Vegetative Features of the Polypodiids We Now

VI. Ferns I: The Marattiales and Vegetative Features of the Polypodiids We now take up the ferns, order Marattiales - a group of large tropical ferns with primitive features - and subclass Polypodiidae, the leptosporangiate ferns. (See the PPG phylogeny on page 48a: Susan, Dave, and Michael, are authors.) Members of these two groups are spore-dispersed vascular plants with siphonosteles and megaphylls. A. Marattiales, an Order of Eusporangiate Ferns The Marattiales have a well-documented history. They first appear as tree ferns in the coal swamps right in there with Lepidodendron and Calamites. (They will feature in your second critical reading and writing assignment in this capacity!) The living species are prominent in some hot forests, both in tropical America and tropical Asia. They are very like the leptosporangiate ferns (Polypodiids), but they differ in having the common, primitive, thick-walled sporangium, the eusporangium, and in having a distinctive stele and root structure. 1. Living Plants Go with your TA to the greenhouse to view the potted Angiopteris. The largest of the Marattiales, mature Angiopteris plants bear fronds up to 30 feet in length! a.These plants, like all ferns, have megaphylls. These megaphylls are divided into leaflets called pinnae, which are often divided even further. The feather-like design of these leaves is common among the ferns, suggesting that ferns have some sort of narrow definition to the kinds of leaf design they can evolve. b. The leaflets are borne on stem-like axes called rachises, which, as you can see, have swollen bases on some of the plants in the lab. -

VI. Ferns I: the Marattiales and the Polypodiales, Vegetative Features We Now Take up the Ferns, Two Orders That Together Inclu

VI. Ferns I: The Marattiales and the Polypodiales, Vegetative Features We now take up the ferns, two orders that together include about 12,000 species. Members of these two orders have megaphylls that bear sporangia either abaxially or (rarely) on the margin of the leaf. In addition, they are all spore-dispersed. In this lab, we'll consider the Marattiales, a group of large tropical ferns with primitive features, and the vegetative features of the Polypodiales, the true ferns. A. Marattiales, an Order of Eusporangiate Ferns The Marattiales have a well-documented history. They first appear as tree ferns in the coal swamps right in there with Lepidodendron and Calamites. The living species are prominent in some hot forests, both in tropical America and tropical Asia. They are very like the true ferns (Polypodiales), but they differ in having the common, primitive, thick-walled sporangium, the eusporangium, and in having a distinctive stele and root structure. 1. Living Plants The large ferns on the tables in the lab this week are members of two genera of the Marattiales, Marattia and Angiopteris. a.These plants, like all ferns, have megaphylls. These megaphylls are divided into leaflets called pinnae, which are often divided even further. The feather-like design of these leaves is common among the ferns, suggesting that ferns have some sort of narrow definition to the kinds of leaf design they can evolve. b. The leaflets are borne on stem-like axes called rachises, which, as you can see, have swollen bases on some of the plants in the lab. -

Tracheophyte of Xiao Hinggan Ling in China: an Updated Checklist

Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e32306 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.7.e32306 Taxonomic Paper Tracheophyte of Xiao Hinggan Ling in China: an updated checklist Hongfeng Wang‡§, Xueyun Dong , Yi Liu|,¶, Keping Ma | ‡ School of Forestry, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China § School of Food Engineering Harbin University, Harbin, China | State Key Laboratory of Vegetation and Environmental Change, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China ¶ University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Corresponding author: Hongfeng Wang ([email protected]) Academic editor: Daniele Cicuzza Received: 10 Dec 2018 | Accepted: 03 Mar 2019 | Published: 27 Mar 2019 Citation: Wang H, Dong X, Liu Y, Ma K (2019) Tracheophyte of Xiao Hinggan Ling in China: an updated checklist. Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e32306. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.7.e32306 Abstract Background This paper presents an updated list of tracheophytes of Xiao Hinggan Ling. The list includes 124 families, 503 genera and 1640 species (Containing subspecific units), of which 569 species (Containing subspecific units), 56 genera and 6 families represent first published records for Xiao Hinggan Ling. The aim of the present study is to document an updated checklist by reviewing the existing literature, browsing the website of National Specimen Information Infrastructure and additional data obtained in our research over the past ten years. This paper presents an updated list of tracheophytes of Xiao Hinggan Ling. The list includes 124 families, 503 genera and 1640 species (Containing subspecific units), of which 569 species (Containing subspecific units), 56 genera and 6 families represent first published records for Xiao Hinggan Ling. The aim of the present study is to document an updated checklist by reviewing the existing literature, browsing the website of National Specimen Information Infrastructure and additional data obtained in our research over the past ten years. -

Cutting Back Ferns – the Art of Fern Maintenance Richie Steffen

Cutting Back Ferns – The Art of Fern Maintenance Richie Steffen When I am speaking about ferns, I am often asked about cutting back ferns. All too frequently, and with little thought, I give the quick and easy answer to cut them back in late winter or early spring, except for the ones that don’t like that. This generally leads to the much more difficult question, “Which ones are those?” This exposes the difficulties of trying to apply one cultural practice to a complicated group of plants that link together a possible 12,000 species. There is no one size fits all rule of thumb. First of all, cutting back your ferns is purely for aesthetics. Ferns have managed for millions of years without being cut back by someone. This means that for ferns you may not be familiar with, it is fine to not cut them back and wait to see how they react to your growing conditions and climate. There are three factors to consider when cutting back ferns: 1. Is your fern evergreen, semi-evergreen, winter-green or deciduous? Deciduous ferns are relatively easy to decide whether to cut back – when they start to yellow and brown in the autumn, cut them to the ground. Some deciduous ferns have very thin fronds and finely divided foliage that may not even need to be cut back in the winter. A light layer of mulch may be enough to cover the old, withered fronds, and they can decay in place. Semi-evergreen types are also relatively easy to manage.