Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bassin Minierdu

Bassin minier du Nord-Pas de Calais Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO Bassin minier du Nord-Pas de Calais I Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO Le 30 juin 2012, lors de sa session annuelle à Saint-Pétersbourg, le Comité du patrimoine mondial a inscrit le Bassin minier du Nord-Pas de Calais sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial, ayant reconnu « la valeur universelle exceptionnelle de ses paysages culturels évolutifs vivants […] ainsi que sa place exceptionnelle dans l’histoire événementielle et sociale du monde de la mine. » (rapport ICOMOS mai 2012) Ce document est une synthèse de la proposition d’inscription co-produite par l’Association Bassin Minier Uni (BMU) et la Mission Bassin Minier (MBM), avec l’appui scientifique du Centre Historique Minier de Lewarde, du CPIE-Chaîne des Terrils et du Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Direction régionale des affaires culturelles. Pour télécharger la proposition d’inscription : http://whc.unesco.org/fr/list/1360/ Sommaire 1 Le Bassin minier, un paysage culturel évolutif vivant page 3 Un ouvrage combiné de l’homme et de la nature Un paysage culturel évolutif Un territoire vivant 2 La Valeur Universelle Exceptionnelle du Bassin minier page 7 La dimension universelle du Bassin minier Son caractère exceptionnel Les critères d’inscription 3 Près de trois siècles d’histoire page 13 4 Le(s) patrimoine(s) du Bassin minier page 17 Le système minier L’empreinte des Compagnies minières et des HBNPC L’héritage technique L’héritage social L’héritage culturel 5 Une mosaïque de paysages page 55 Le socle topographique -

Recueil Des Actes Administratifs

PRÉFET DU PAS-DE-CALAIS RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS RECUEIL n° 23 du 5 avril 2019 Le Recueil des Actes Administratifs sous sa forme intégrale est consultable en Préfecture, dans les Sous-Préfectures, ainsi que sur le site Internet de la Préfecture (www.pas-de-calais.gouv.fr) rue Ferdinand BUISSON - 62020 ARRAS CEDEX 9 tél. 03.21.21.20.00 fax 03.21.55.30.30 PREFECTURE DU PAS-DE-CALAIS.......................................................................................3 - Arrêté préfectoral accordant la médaille d’honneur communale, départementale et régionale..........................................3 - Arrêté préfectoral accordant la médaille d’honneur agricole............................................................................................53 MINISTERE DE LA JUSTICE-DIRECTION INTERREGIONALE DES SERVICES PENITENTIAIRES...................................................................................................................61 Maison d’arrêt d’Arras........................................................................................................................................................61 Décision du 2 avril 2019 portant délégation de signature...................................................................................................61 DIRECCTE HAUTS-DE-FRANCE..........................................................................................62 - Modifications apportées à la décision du 30 novembre 2018 portant affectation des agents de contrôle dans les unités de contrôle et organisation -

Mouvement Départemental Du Pas-De-Calais Enseignants Du 1Er Degré Public 2021

MOUVEMENT DÉPARTEMENTAL DU PAS-DE-CALAIS ENSEIGNANTS DU 1ER DEGRÉ PUBLIC 2021 LISTE N°2 REGROUPEMENTS GÉOGRAPHIQUES ET COMMUNES RATTACHÉES ACHICOURT et ARRAS Sud ACHICOURT FICHEUX ADINFER HENDECOURT LES RANSART AGNY HENINEL BEAUMETZ LES LOGES HENIN SUR COJEUL BEAURAINS MERCATEL BERNEVILLE NEUVILLE VITASSE BLAIRVILLE RANSART BOIRY BECQUERELLE RIVIÈRE BOIRY ST MARTIN SAINT MARTIN SUR COJEUL BOIRY STE RICTRUDE TILLOY LES MOFFLAINES BOISLEUX AU MONT WAILLY BOYELLES WANCOURT AIRE SUR LA LYS AIRE SUR LA LYS ROQUETOIRE BLESSY WARDRECQUES RACQUINGHEM WITTES ANNEZIN ANNEZIN VENDIN LES BÉTHUNE HINGES ARDRES ARDRES NORDAUSQUES BALINGHEM RODELINGHEM BRÈMES TOURNEHEM SUR LA HEM LANDRETHUN LES ARDRES ZOUAFQUES LOUCHES ARQUES et LONGUENESSE ARQUES LONGUENESSE CAMPAGNE LES WARDRECQUES ARRAS Ville ARRAS ARRAS Nord ACQ MONT ST ÉLOI ANZIN ST AUBIN SAINTE CATHERINE DAINVILLE THELUS DUISANS VIMY MAROEUIL AUBIGNY AGNIERES FREVILLERS AMBRINES FREVIN CAPELLE AUBIGNY EN ARTOIS HERMAVILLE BAJUS IZEL LES HAMEAUX BERLES MONCHEL MAGNICOURT EN COMTE BETHONSART PENIN CAMBLIGNEUL SAVY BERLETTE CAMBLAIN L’ABBÉ TILLOY LES HERMAVILLE CHELERS TINCQUES LA COMTE VILLERS BRULIN ESTREE CAUCHY VILLERS CHATEL AUCHEL AMES FERFAY AMETTES LOZINGHEM AUCHEL LIÈRES CAUCHY A LA TOUR AUCHY LES HESDIN AUCHY LES HESDIN LE PARCQ BLANGY SUR TERNOISE ROLLANCOURT GRIGNY WAMIN AUCHY LES MINES AUCHY LES MINES GIVENCHY LES LA BASSÉE CAMBRIN HAISNES CUINCHY VIOLAINES AUDRUICQ AUDRUICQ RECQUES SUR HEM MUNCQ NIEURLET RUMINGHEM NORTKERQUE SAINTE MARIE KERQUE POLINCOVE ZUTKERQUE AUXI LE CHÂTEAU AUXI -

Liste Des Communes Situées Sur Une Zone À Enjeu Eau Potable

Liste des communes situées sur une zone à enjeu eau potable Enjeu eau Nom commune Code INSEE potable ABANCOURT 59001 Oui ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Oui ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Oui ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Oui ACHICOURT 62004 Oui ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Oui ADINFER 62009 Oui AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Oui AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Oui AIBES 59003 Oui AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Oui AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Oui AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Oui AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Oui AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Oui AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Oui ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Oui ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non Page 1/59 Liste des communes situées sur une zone à enjeu eau potable Enjeu eau Nom commune Code INSEE potable ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Oui ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Oui ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Oui AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Oui AMY 60011 Oui ANDAINVILLE 80022 Non ANDECHY 80023 Oui ANDRES 62031 Oui ANGRES 62032 Oui ANHIERS 59007 Non ANICHE 59008 Oui ANNAY 62033 -

Arrêté Du 25 Septembre 2017 Portant Dissolution De La Brigade Territoriale

OK mauvais BULLETIN OFFICIEL DU MINISTÈRE DE L’INTÉRIEUR MINISTÈRE DE L’INTÉRIEUR _ Direction générale de la gendarmerie nationale _ Direction des soutiens et des finances _ Arrêté du 25 septembre 2017 portant dissolution de la brigade territoriale de Houdain (Pas-de-Calais) NOR : INTJ1731365A Le ministre d’État, ministre de l’intérieur, Vu le code de la défense ; Vu le code de procédure pénale, notamment ses articles 15-1 et R. 15-22 à R. 15-26 ; Vu le code de la sécurité intérieure, notamment son article L. 421-2, Arrête : Article 1er La brigade territoriale de Houdain (Pas-de-Calais) est dissoute à compter du 1er novembre 2017. Corrélativement, les circonscriptions des brigades territoriales de Hersin-Coupigny et de Béthune sont modifiées à la même date dans les conditions précisées en annexe. Article 2 Les officiers, gradés et gendarmes des brigades territoriales de Hersin-Coupigny et de Béthune exercent les attributions attachées à leur qualité d’officier ou d’agent de police judiciaire dans les conditions fixées aux articles R. 13 à R. 15-2 et R. 15-24 (1°) du code de procédure pénale. Article 3 Le directeur général de la gendarmerie nationale est chargé de l’exécution du présent arrêté, qui sera publié au Bulletin officiel du ministère de l’intérieur. FFi l 25 septembre 2017. Pour le ministre d’État et par délégation : Le général de corps d’armée, directeur des soutiens et des finances, L. TAVEL 15 DÉCEMBRE 2017. – INTÉRIEUR 2017-12 – PAGE 185 BULLETIN OFFICIEL DU MINISTÈRE DE L’INTÉRIEUR ANNEXE BRIGADE TERRITORIALE CIRCONSCRIPTION -

Saveurs Savoir-Faire

Saveurs & savoir-faire en Côte d’Opale GUIDE 2020 des producteurs locaux Edito En cette année particulière, le confinement nous a fait redécouvrir nos producteurs locaux et combien nous avons besoin d’eux. Parce qu’ils sont gage de proximité, de qualité mais aussi de convivialité et de partage. Avec ce nouveau rapport au temps pendant cette longue parenthèse, petits et grands, parents et enfants se sont réappropriés les plaisirs simples d’une recette partagée, réalisée avec de bons produits. Retrouvez tous les producteurs agricoles et artisanaux dans ce guide, pour faciliter l’approvisionnement de chacun, touriste ou habitant. Fromages, fruits et légumes, yaourts et autres produits laitiers, boissons, gourmandises, viandes et poissons, la gamme est large pour se faire plaisir, bien manger et soutenir notre économie locale. Même avec distanciation, les producteurs sauront vous accueillir pour vous faire découvrir et déguster leurs produits. Daniel Fasquelle Président de l’Agence d’Attractivité Opale&CO Les produits locaux font partie de la richesse et de l’identité des territoires. Pendant cette période inédite, les agriculteurs ont montré leur capacité d’adaptation pour continuer de produire et vous approvisionner en produits locaux de qualité. Nous sommes heureux de leur mise en lumière à travers ce guide «Saveurs et Savoir Faire» réalisé par Opale&Co. A nous citoyens, d’être consomm’acteurs afin de faire vivre nos producteurs et artisans. Sur les marchés, dans les magasins, en direct à la ferme, via des distributeurs automatiques ou encore avec le Drive fermier du Montreuillois, les agriculteurs vous donnent rendez-vous tout au long de l’année pour vous proposer leurs produits pleins de saveurs. -

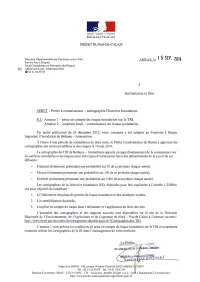

ARRAS Le F 5 SEP, 2014

Liberré • Egalité • Fraternité •RÉPUBLI QUE FRANÇAISE PRÉFET DU PAS-DE-CALAIS Direction Dépa rtementale des Tenitoires et de la Mer ARRAS , le f 5 SEP, 2014 Service Eau et Risques Unité Connaissance et Prévention des Risques セ@ Affaire suivie par : Emmanuel Duée w 03.2 1.22.99. 78 à destinataires in fine OBJET : Porter à connaissance - cartographie Directive Inondation. P.J.: Annexe 1 - prise en compte du risque inondation sur le TRI. Annexe 2 - contexte local - connaissance du risque inondation. Par arrêté préfectoral du 26 décembre 201 2, votre commune a été intégrée au Territoire à Risque Important d'inondation de Béthune - Armentières. À l' issue d'une période de consultation de deux mois, le Préfet Coordonnateur de Bassin a approuvé les cartographies des zones inondables et des risques le 16 mai 2014. La cartographie du TRI de Béthune - Armentières apporte un approfondissement de la connaissance sur les surfaces inondables et les risques pour trois types d'événements liés à des débordements de la Lys et de ses affluents : Fréquent (événement présentant une probabilité sur 10 de se produire chaque année). Moyen (événement présentant une probabilité sur 100 de se produire chaque année). Extrême (événement présentant une probabilité sur 1000 de se produire chaque année). Les cartographies de la Directive Inondation (DI), élaborées pour être exploitées à l'échelle l/25000e, ont pour obj ectifs de contribuer : 1. à l'élaboration des plans de gestion du risque inondation et des stratégies locales, 2. à la sensibilisation du public, 3. à la prise en compte du risque dans l'urbanisme et l'application du droit des sols. -

Juillet 2017

Informations aux Employeurs Juillet 2017 Ce qui change au 1er juillet 20117 Versement de la cotisation • Communauté urbaine d’Arras : Adhésion des communes suivantes Basseux, Boiry St Martin, Boiry Ste Rictrude, Ficheux, Ransart, Rivière et Roeux au 1er janvier 2017 (taux de 0,90 % appliqué au 1er juillet 2017). Pas de changement pour les autres communes : 0,90 %. • Syndicat Mixte des Transports Artois Gohelle : Pour les communes de Allouagne, Ames, Amettes, Auchy au Bois, Blessy, Bourecq, Burbure, Busnes, Calonne sur la Lys, Ecquedecques, Estree Blanche, Ferfay ; Gonnehem, Guarbecque, Ham en Artois, Isbergues, Lambres Lez Aire, Lespesses, Lieres, Liettres, Ligny Les Aire, Lilliers, Linghem, Mazinghem, Mont Bernenchon, Norrent Fontes, Quernes, Rely, Robecq, Rombly, St-Floris, St-Hilaire Cottes, St Venant, Westrehem et Witternesse, le taux de transport est de 0,20 %. Pas de changement pour les autres communes : 1,60 %. • Métropole Européenne de Lille : Pour les communes de Aubers, Bois Grenier, Fromelles, Le Maisnil et Radinghem en Weppes, le taux est fixé à 0,17 %. Pas de changement de taux pour les autres communes : 2 % Régime de prévoyance des ETAR du Nord – Pas de Calais A compter du 1er juillet 2017, l’accord prévoyance des ETAR passe en référencement. Désormais, l’employeur choisit son organisme assureur. L’organisme assureur Agri prévoyance (Agrica) a confié à la MSA le recouvrement des cotisations prévoyance pour les salariés non cadres. Les taux de cotisations évoluent au 1er juillet 2017 : Branche Part ouvrière Part patronale -

Recensement Des Études Pédologiques Réalisées Pour Les Études De Drainage Ou Assainissement, Base De Données DRAF

Recensement des études pédologiques réalisées pour les études de drainage ou assainissement, Base de données DRAF ARTOIS (15) Nb études Et DR Et SDA Aix Noulette 0 Billy-Berclaux 0 Bouvigny Boyeffles 3 2 1 Bully les Mines 0 Douvrin 0 Givenchy-La Bassée 0 Grenay 0 Haisnes 0 Hersin Coupigny 1 0 1 Lorgies 1 0 1 Mazingarbe 0 Noyelles les Vermelles 0 Vermelles 0 Violaines 5 5 0 Sains en Gohelle 0 0 0 TOTAL 10 7 3 PAYS D'AIRE (51) Nb études Et DR Et SDA Aire sur la Lys 5 3 2 Ames 1 0 1 Amettes 1 0 1 Auchy au Bois 0 Aumerval 1 0 1 Bailleul les Pernes 1 0 1 Berguette 0 Blessy 2 1 1 Bourecq 3 2 1 Campagne les W. 0 Clarques 0 Delette 0 Dohem 0 Ecquedecques 4 3 1 Ecques 1 1 0 Enguinegatte 1 0 1 Enquin les Mines 1 0 1 Erny Saint Julien 1 0 1 Estree Blanche 1 0 1 Ferfay 1 0 1 Fontaine les Hermans 1 0 1 Ham en Artois 4 3 1 Herbelles 0 Heuringhem 0 Inghem 0 Isbergues 0 Lambres 1 1 0 Lespesse 1 0 1 Lieres 1 0 1 Liettres 1 0 1 Ligny les Aires 1 0 1 Linghem 1 0 1 Mametz 0 Mazhinghem 1 0 1 Molinghem 1 0 1 Nedon 1 0 1 Nedonchel 1 0 1 Norrent Fonte 1 0 1 Quernes 1 0 1 Questede 1 0 1 Racquinghem 4 4 0 Rebecques 1 1 0 Rely 1 0 1 Rombly 2 1 1 Roquetoire 3 2 1 Saint Hilaire Cottes 1 0 1 Therouanne 0 Wardrecques 2 2 1 Westrehem 1 0 1 Wittes 0 Witternesse 2 1 1 TOTAL 59 25 35 HAUT PI D'ARTOIS Nb études Et DR Et SDA Audincthun 1 0 1 Beaumetz-lès-Aires 0 Bomy 1 0 1 Canlers 1 0 1 Coupelle Neuve 1 0 1 Coupelle vieille 0 Coyecques 1 0 1 Dennebroeucq 1 0 1 Febvin Palfard 1 0 1 Flechin 1 0 1 Fruges 1 1 0 Hezecques 1 1 0 Laires 1 0 1 Lisbourg 2 1 1 Lugy 1 1 0 Matringhem -

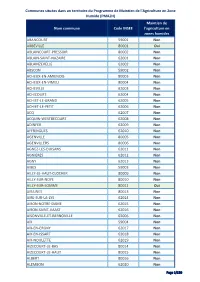

(PMAZH) Nom Commune Code INSEE

Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ABANCOURT 59001 Non ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Non ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Non ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Non ACHICOURT 62004 Non ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Non ADINFER 62009 Non AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Non AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Non AIBES 59003 Non AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Non AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Non AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Non AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Non AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Non AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Non Page 1/130 Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Non ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Non ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Non ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Non AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Non AMY -

La Ferme Seigneuriale Et La Ferme-Manoir

La ferme seigneuriale et Fiche la ferme-Manoir Patrimoine Bezinghem - Manoir du Pucelart ’insécurité constante qui rLègne dans le Mon - treuillois et le Boulon - nais jusqu’au XVII e siècle est à l’origine d’un type d’habitat sei - gneurial spécifique qui croise les fonctions d’habitation noble et d’exploitation agri - cole. Cette double vocation a généré une disposition typique. Le corps de logis, généralement à étage, est divisé en deux maisons distinctes, la résidence du seigneur et celle du fermier, chacune signalée par un accès propre. Les deux logis sont parfois distincts comme au manoir du Pucelart à Bezinghem où la maison du fermier en torchis faisait corps avec l’écurie. Leur architecture es constructions massives et dépourvues de confort sont élevées par une aristocratie peu fortunée aux XVI e et XVII e siècle. Le Pucelart, daté de 1511 par les ancres est peut-être l’une des plus anciennes. Dans le fronton qui coiffe la pCorte du manoir de Thubeauville est inscrite en relief la date de 1635. Les façades sont sobres et peu Parenty - Manoir de Thubeauville ornementées, les ouvertures peu nombreuses et de petites dimensions. A la Beauce, sur les hauteurs de Neuville-sous- Montreuil, et au Ménage d’Alette, un jeu de briques foncées crée un décor de losanges entre les baies de l'étage. A Thubeauville, la porte est surmontée d’un fronton triangulaire. Au hameau de Zélucques à Tubersent, une niche moulurée surmontée d’un arc en accolade et un larmier ornent un pignon. Lefaux - Manoir du Fayel Les Matériaux Outre ces analogies dans les volumes et la dis - position intérieure, les logis seigneuriaux du Montreuillois sont majoritairement élevés en briques comme le manoir du Fayel à Lefaux. -

Official Journal C 337 Volume 37 of the European Communities 1 December 1994

ISSN 0378-6986 Official Journal C 337 Volume 37 of the European Communities 1 December 1994 English edition Information and Notices Notice No Contents Page I Information Council 94/C 337/01 Council notice 1 Commission 94/C 337/02 Ecu 2 94/C 337/03 Average prices and representative prices for table wines at the various marketing centres 3 94/C 337/04 Notice to the Member States establishing the list of areas for assistance in the framework of a Community initiative concerning the economic conversion of coal mining areas (Rechar II) 4 EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AREA EFTA Surveillance Authority 94/C 337/05 Notice pursuant to Article 19 (3) of Chapter II of Protocol 4 to the Agreement between the EFTA States on the establishment of a Surveillance Authority and Court of Justice concerning Case No COM 0006 — Metsäteollisuus Ry — Skogs industrin Rf and Case No COM 0105 — Maa- ja metsataloustuottajain Keskusliitto MTK ry 21 1 (Continued overleaf) Notice No Contents (continued) Page II Preparatory Acts Council 94/C 337/06 Assent No 30/94 given by the Council, acting unanimously pursuant to the second paragraph of Article 54 of the Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community, for the granting of a global loan to Mediocredito Centrale, Rome (Italy) to finance investment programmes which contribute to facilitating the marketing of Community steel 23 III Notices Commission 94/C 337/07 Amendment to notice of invitation to tender for the refund for the export of milled medium-grain and long-grain A rice to certain third countries 24 94/C 337/08