Chapter 4: the Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

Today We Are Interviewing Mr

1 CENTER FOR FLORIDA HISTORY ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: HOMER HOOKS INTERVIEWER: JAMES M. DENHAM PLACE: LAKELAND, FLORIDA DATE: JULY 29, 2003 M= JAMES M. DENHAM (Mike) H= HOMER HOOKS M: Today we are interviewing Mr. Homer Hooks and we are going to talk today about the legacy of Lawton Chiles and hopefully follow this up with future discussions of Mr. Hooks’ business career and career in politics. Good morning Mr. Hooks. H: Good morning, Mike. M: As I mentioned, we, really, in the future want to talk about your service in World War II and also your business career, but today we would like to focus on your memories of Lawton Chiles. Even so, can you tell us a little bit about where you were born as well as giving us a brief biographical sketch? H: Yes, Mike. I was born in Columbia, South Carolina, on January 10, 1921. My family moved to Lake County actually in Florida when I was a child. I was 4 or 5 years old, I guess. We lived in Clermont in south Lake County. My grandfather was a pioneer. He platted the town of Clermont. The rest of the family also lived north of Clermont in the Leesburg area, but we considered ourselves pioneer Florida residents. Those were the days in 1926, ‘27 and ‘28 days and so forth. I grew up in Clermont - grammar school and high school and then immediately went to the University of Florida in 1939 and graduated in 1943, as some people have said, when the earth’s crust was still cooling, so long ago. -

Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources

Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources Everglades National Park was created primarily because of its unique flora and fauna. In the 1920s and 1930s there was some limited understanding that the park might contain significant prehistoric archeological resources, but the area had not been comprehensively surveyed. After establishment, the park’s first superintendent and the NPS regional archeologist were surprised at the number and potential importance of archeological sites. NPS investigations of the park’s archeological resources began in 1949. They continued off and on until a more comprehensive three-year survey was conducted by the NPS Southeast Archeological Center (SEAC) in the early 1980s. The park had few structures from the historic period in 1947, and none was considered of any historical significance. Although the NPS recognized the importance of the work of the Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs in establishing and maintaining Royal Palm State Park, it saw no reason to preserve any physical reminders of that work. Archeological Investigations in Everglades National Park The archeological riches of the Ten Thousand Islands area were hinted at by Ber- nard Romans, a British engineer who surveyed the Florida coast in the 1770s. Romans noted: [W]e meet with innumerable small islands and several fresh streams: the land in general is drowned mangrove swamp. On the banks of these streams we meet with some hills of rich soil, and on every one of those the evident marks of their having formerly been cultivated by the savages.812 Little additional information on sites of aboriginal occupation was available until the late nineteenth century when South Florida became more accessible and better known to outsiders. -

Hugh Taylor Birch State Park 05-2020

Ron DeSantis FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF Governor Jeanette Nuñez Environmental Protection Lt. Governor Marjory Stoneman Douglas Building Noah Valenstein 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard Secretary Tallahassee, FL 32399 Memorandum TO: James Parker Office of Environmental Services Division of State Lands FROM: Yasmine Armaghani Office of Park Planning Division of Recreation and Parks SUBJECT: Hugh Taylor Birch State Park Ten Year Management Plan Update (Lease No. 3624) Acquisition and Restoration Council (ARC) Public Hearing DATE: May 12, 2020 Attached for your convenience and use are five discs with the subject management plan update file. Contained on the discs is the ARC executive summary, the Division of State Lands checklist and a copy of the subject management plan update. This plan is being submitted for the Division of State Lands’ compliance review and for review by ARC members at their August 2020 meeting. An electronic version of the document is available on the DEP Park Planning Public Participation webpage at the following link: https://floridadep.gov/parks/parks-office-park- planning/documents/hugh-taylor-birch-state-park-05-2020-arc-draft-unit. Please contact me by email at [email protected] if there are any questions related to this amendment. Thank you for your assistance. YA:dpd Attachments cc: Deborah Burr Land ManageMent PLan ComplianCe CheCkList → Required for State-owned conservation lands over 160 acres ← Instructions for managers: Complete each item and fill in the applicable correlating page numbers and/or appendix where the item can be found within the land management plan (LMP). If an item does not apply to the subject property, please describe that fact on a correlating page number of the LMP. -

Vegetation Trends in Indicator Regions of Everglades National Park Jennifer H

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons GIS Center GIS Center 5-4-2015 Vegetation Trends in Indicator Regions of Everglades National Park Jennifer H. Richards Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, [email protected] Daniel Gann GIS-RS Center, Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/gis Recommended Citation Richards, Jennifer H. and Gann, Daniel, "Vegetation Trends in Indicator Regions of Everglades National Park" (2015). GIS Center. 29. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/gis/29 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the GIS Center at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GIS Center by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Final Report for VEGETATION TRENDS IN INDICATOR REGIONS OF EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK Task Agreement No. P12AC50201 Cooperative Agreement No. H5000-06-0104 Host University No. H5000-10-5040 Date of Report: Feb. 12, 2015 Principle Investigator: Jennifer H. Richards Dept. of Biological Sciences Florida International University Miami, FL 33199 305-348-3102 (phone), 305-348-1986 (FAX) [email protected] (e-mail) Co-Principle Investigator: Daniel Gann FIU GIS/RS Center Florida International University Miami, FL 33199 305-348-1971 (phone), 305-348-6445 (FAX) [email protected] (e-mail) Park Representative: Jimi Sadle, Botanist Everglades National Park 40001 SR 9336 Homestead, FL 33030 305-242-7806 (phone), 305-242-7836 (Fax) FIU Administrative Contact: Susie Escorcia Division of Sponsored Research 11200 SW 8th St. – MARC 430 Miami, FL 33199 305-348-2494 (phone), 305-348-6087 (FAX) 2 Table of Contents Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

Michael Gannon Endowment Supports Florida History

SPRING 2019 FOR FRIENDS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GEORGE A. SMATHERS LIBRARIES Michael Gannon Endowment supports Florida history The Smathers Libraries have photographs, biographical materials enjoyed a screening of a spoof film, launched an initiative to build an and other documents of Gannon, the Return of the Creature, written and endowment in honor of the late noted historian, radio commentator filmed by a 27-year-old Michael Distinguished Service Professor and former priest. He was an Gannon at Marineland in 1954. Emeritus, Dr. Michael Gannon. expert on Florida history from its Annually, the endowment will Spanish founding through the U.S. Those interested in making a gift sponsor a prominent speaker on Civil War, and on World War II. to support the Michael Gannon the subject of Florida history or the Endowment can use the pledge history of World War II. A Guide to the Michael Gannon card at https://cms.uflib.ufl. Papers can be found at http://ufdc. edu/portals/communications/ Gannon donated his papers to ufl.edu/gannon. GannonPledgeCard.pdf. the Smathers Libraries and they officially opened at a reception The Libraries hosted an inaugural in November 2016. The Michael fundraising event with Genevieve Gannon Papers include writings, (Gigi) Haugen Gannon on March 27 research notes, correspondence, at the Flagler College Solarium in St. Augustine, Florida. The guests ABOVE: Scene from the 1954 Michael Gannon spoof, Return of the Creature. Gannon is on the right. LEFT: Dean of University Libraries Judith Russell, with co-hosts of the St. Augustine reception, Allen & Delores Lastinger, Genevieve Haugen Gannon, Kathleen Deagan and Mark & Alecia Bailey. -

Report SFRC-83/01 Status of the Eastern Indigo Snake in Southern Florida National Parks and Vicinity

Report SFRC-83/01 Status of the Eastern Indigo Snake in Southern Florida National Parks and Vicinity NATIONAL b lb -a'*? m ..-.. # .* , *- ,... - . ,--.-,, , . LG LG - m,*.,*,*, Or 7°C ,"7cn,a. Q*Everglades National Park, South Florida Research Center, P.O.Box 279, Homestead, Florida 33030 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ........................... 1 STUDYAREA ............................ 1 METHODS .............................. 3 RESULTS .............................. 4 Figure 1. Distribution of the indigo snake in southern Florida ..... 5 Figure 2 . Distribution of the indigo snake in the Florida Keys including Biscayne National Park ............. 6 DISCUSSION ............................. 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................ 13 LITERATURE CITED ......................... 14 APPENDIX 1. Observations of indigo snakes in southern Florida ....... 17 APPENDIX 2 . Data on indigo snakes examined in and adjacent to Everglades National Park ................. 24 APPENDIX 3. Museum specimens of indigo snakes from southern Florida ... 25 4' . Status of the Eastern Indigo Snake in Southern Florida National Parks and Vicinity Report ~F~~-83/01 Todd M. Steiner, Oron L. Bass, Jr., and James A. Kushlan National Park Service South Florida Research Center Everglades National Park Homestead, Florida 33030 January 1983 Steiner, Todd M., Oron L. Bass, Jr., and James A. Kushlan. 1983. Status of the Eastern Indigo Snake in Southern Florida National Parks and Vicinity. South Florida Research Center Report SFRC- 83/01. 25 pp. INTRODUCTION The status and biology of the eastern indigo snake, Drymarchon corais couperi, the largest North American snake (~awler,1977), is poorly understood. Destruction of habitat and exploitation by the pet trade have reduced its population levels in various localities to the point that it is listed by the Federal government as a threatened species. -

MERCHANTS BANK 1 Sale

BARBER SHOP W. C. SMITH DR. W. R DAVEY 5J5?S I5E(Si i:: TCLACavyORX IMC mm haapttal cMNMham -- ttANUFACTUnSnS C?TtCil 3 f cr: CHOP IN THE CITY GINGER ALE AND CLU3 CODA srr pooa to poctotwcb J L- C C BOMANNON. M?? 151 SsKtfc r-rNo.- 37J Daytona, Florida MondaViJanuary 15, 1917 1 "CUR CALOT-O- " I.QLJ ILJtL. A , . - 1 1 vv-M- , LJ' L . 11 1111 r J 111 I Hi CU1 III III , " , 1: J JV J "V B UaVC III - lZr'v u; II! U W v - v v - ' eolers from the most cblicate to some 17 0 DDF reds like the "fair ones" faces show. - 0:7S CZ2I LAS Ql Si LL TO o:ty 4C0 FEET GRUBER-MORIU- CII-STOCICED-Y OClt S HARDWARE CO. a COW OF YEARS SWEEP- SGUTll OF THE FERilY innEffTivouMS CONVICTION OF F. CC- -1 ER TENNESSEE, ARKANSAS Ctt ETTI AND UAUHV L CRICC3 CF f-- D NORTHERN MISSISSIPPI FERRY LOCATION IS AT BEND Deutcchlcmd Coieved Again BE CALIFORNIA COKFIRZTSD BY APP- CTCSSI GENERAL IN WEST. OF RIVER AND WAR DEPART- WILL .CERTIFIED, ADVERTIS- ED AND AND ELLATE COURT. (Tfci Associated Press.) MENT WANTS DIFFERENT LO Newring Shores of America SOLD WORK ON t - rtonm j ar swooping the CATION. (The Associated Press.) THAT PORTION OF DIXIE .HIGH- WASHINGTON. Jan. IS. Proseco--. Cr-- tr frtton of tho northern and WAY COMPLETED AT ONCE. tions are transporting women firocs. -- states, attended by a cold Michael Sholtz will in all probabil- NEW YORK. Jan. 15. An unidenti- - ing here today from Bordeaux. -

Restoring Southern Florida's Native Plant Heritage

A publication of The Institute for Regional Conservation’s Restoring South Florida’s Native Plant Heritage program Copyright 2002 The Institute for Regional Conservation ISBN Number 0-9704997-0-5 Published by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue Miami, Florida 33170 www.regionalconservation.org [email protected] Printed by River City Publishing a division of Titan Business Services 6277 Powers Avenue Jacksonville, Florida 32217 Cover photos by George D. Gann: Top: mahogany mistletoe (Phoradendron rubrum), a tropical species that grows only on Key Largo, and one of South Florida’s rarest species. Mahogany poachers and habitat loss in the 1970s brought this species to near extinction in South Florida. Bottom: fuzzywuzzy airplant (Tillandsia pruinosa), a tropical epiphyte that grows in several conservation areas in and around the Big Cypress Swamp. This and other rare epiphytes are threatened by poaching, hydrological change, and exotic pest plant invasions. Funding for Rare Plants of South Florida was provided by The Elizabeth Ordway Dunn Foundation, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and the Steve Arrowsmith Fund. Major funding for the Floristic Inventory of South Florida, the research program upon which this manual is based, was provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Steve Arrowsmith Fund. Nemastylis floridana Small Celestial Lily South Florida Status: Critically imperiled. One occurrence in five conservation areas (Dupuis Reserve, J.W. Corbett Wildlife Management Area, Loxahatchee Slough Natural Area, Royal Palm Beach Pines Natural Area, & Pal-Mar). Taxonomy: Monocotyledon; Iridaceae. Habit: Perennial terrestrial herb. Distribution: Endemic to Florida. Wunderlin (1998) reports it as occasional in Florida from Flagler County south to Broward County. -

For Indian River County Histories

Index for Indian River County Histories KEY CODES TO INDEXES OF INDIAN RIVER COUNTY HISTORIES Each code represents a book located on our shelf. For example: Akerman Joe A, Jr., M025 This means that the name Joe Akerman is located on page 25 in the book called Miley’s Memos. The catalog numbers are the dewey decimal numbers used in the Florida History Department of the Indian River County Main Library, Vero Beach, Florida. Code Title Author Catalog No. A A History of Indian River County: A Sense of Sydney Johnston 975.928 JOH Place C The Indian River County Cook Book 641.5 IND E The History of Education in Indian River Judy Voyles 975.928 His County F Florida’s Historic Indian River County Charlotte 975.928.LOC Lockwood H Florida’s Hibiscus City: Vero Beach J. Noble Richards 975.928 RIC I Indian River: Florida’s Treasure Coast Walter R. Hellier 975.928 Hel M Miley’s Memos Charles S. Miley 975.929 Mil N Mimeo News [1953-1962] 975.929 Mim P Pioneer Chit Chat W. C. Thompson & 975.928 Tho Henry C. Thompson S Stories of Early Life Along the Beautiful Indian Anna Pearl 975.928 Sto River Leonard Newman T Tales of Sebastian Sebastian River 975.928 Tal Area Historical Society V Old Fort Vinton in Indian River County Claude J. Rahn 975.928 Rah W More Tales of Sebastian Sebastian River 975.928 Tal Area Historical Society 1 Index for Indian River County Histories 1958 Theatre Guild Series Adam Eby Family, N46 The Curious Savage, H356 Adams Father's Been to Mars, H356 Adam G, I125 John Loves Mary, H356 Alto, M079, I108, H184, H257 1962 Theatre Guild -

Florida Jewish History Month January

Florida Jewish History Month January Background Information In October of 2003, Governor Jeb Bush signed a historic bill into law designating January of each year as Florida Jewish History Month. The legislation for Florida Jewish History Month was initiated at the Jewish Museum of Florida by, the Museum's Founding Executive Director and Chief Curator, Marcia Zerivitz. Ms. Zerivitz and State Senator Gwen Margolis worked closely with legislators to translate the Museum's mission into a statewide observance. It seemed appropriate to honor Jewish contributions to the State, as sixteen percent, over 850,000 people of the American Jewish community lives in Florida. Since 1763, when the first Jews settled in Pensacola immediately after the Treaty of Paris ceded Florida to Great Britain from Spain, Jews had come to Florida to escape persecution, for economic opportunity, to join family members already here, for the climate and lifestyle, for their health and to retire. It is a common belief that Florida Jewish history began after World War II, but in actuality, the history of Floridian Jews begins much earlier. The largest number of Jews settled in Florida after World War II, but the Jewish community in Florida reaches much further into the history of this State than simply the last half-century. Jews have actively participated in shaping the destiny of Florida since its inception, but until research of the 1980s, most of the facts were little known. One such fact is that David Levy Yulee, a Jewish pioneer, brought Florida into statehood in 1845, served as its first U.S. -

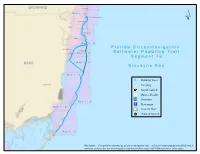

Segment 16 Map Book

Hollywood BROWARD Hallandale M aa p 44 -- B North Miami Beach North Miami Hialeah Miami Beach Miami M aa p 44 -- B South Miami F ll o r ii d a C ii r c u m n a v ii g a tt ii o n Key Biscayne Coral Gables M aa p 33 -- B S a ll tt w a tt e r P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll S e g m e n tt 1 6 DADE M aa p 33 -- A B ii s c a y n e B a y M aa p 22 -- B Drinking Water Homestead Camping Kayak Launch Shower Facility Restroom M aa p 22 -- A Restaurant M aa p 11 -- B Grocery Store Point of Interest M aa p 11 -- A Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Segment 16: Biscayne Bay Little Pumpkin Creek Map 1 B Pumpkin Key Card Point Little Angelfish Creek C A Snapper Point R Card Sound D 12 S O 6 U 3 N 6 6 18 D R Dispatch Creek D 12 Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve 3 ´ Ocean Reef Harbor 12 Wednesday Point 12 Card Point Cut 12 Card Bank 12 5 18 0 9 6 3 R C New Mahogany Hammock State Botanical Site 12 6 Cormorant Point Crocodile Lake CR- 905A 12 6 Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park Mosquito Creek Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge Dynamite Docks 3 6 18 6 North Key Largo 12 30 Steamboat Creek John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park Carysfort Yacht Harbor 18 12 D R D 3 N U O S 12 D R A 12 C 18 Basin Hills Elizabeth, Point 3 12 12 12 0 0.5 1 2 Miles 3 6 12 12 3 12 6 12 Segment 16: Biscayne Bay 3 6 Map 1 A 12 12 3 6 ´ Thursday Point Largo Point 6 Mary, Point 12 D R 6 D N U 3 O S D R S A R C John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park 5 18 3 12 B Garden Cove Campsite Snake Point Garden Cove Upper Sound Point 6 Sexton Cove 18 Rattlesnake Key Stellrecht Point Key Largo 3 Sound Point T A Y L 12 O 3 R 18 D Whitmore Bight Y R W H S A 18 E S Anglers Park R 18 E V O Willie, Point Largo Sound N: 25.1248 | W: -80.4042 op t[ D A I* R A John Pennekamp State Park A M 12 B N: 25.1730 | W: -80.3654 t[ O L 0 Radabo0b.