Trapped in the Hot Box 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1953 Topps, a Much Closer Look

In 1984, Lew Lipset reported that Bob Sevchuk reconstructed the first print run Sheets A and B. 1953 Topps, a much closer look By George Vrechek Tom Billing of Springfield, Ohio, is a long-time collector of vintage baseball cards. Billing is among a small group of collectors who continue to stay enthused about old cardboard by discovering and collecting variations, printing differences and other oddities. Often such discoveries are of interest to a fairly limited audience. Occasionally though, such discoveries amount to a loose string that, if pulled, unravel mysteries of interest to many. I pulled on one of Tom’s strings recently. Sid Hudson throws the first curve The “string” that Billing sent me was an image of a miscut 1953 Topps of Sid Hudson. The right edge of the base of the off-centered card had a tiny sliver of black to the right of the otherwise red base nameplate. Was this a variation, a printing difference or none of the above? Would anyone care? As I thought about it, I voted for none of the above since it was really just a miscut card showing some of the adjacent card on the print sheet. But wait a minute! That shouldn’t have happened with the 1953 Topps. Why not? We will see. The loose string was an off-center Lou Hudson showing an adjacent black border. An almost great article Ten years ago I wrote an SCD article about the printing of the 1952 Topps. I received some nice feedback on that effort in which I utilized arithmetic, miscuts and partial sheets to offer an explanation of how the 1952 set was printed and the resulting scarcities. -

Win, Lose Or Draw

Farm and Garden J&undai} Jfclaf ISpaffe Obituaries C ** TWELVE PAGES. WASHINGTON, D. C., APRIL 4, 1954 Senators' Six-Run Splurge in Ninth Downs Cincinnati, 12 to 7 V me Win, Lose or Draw Royal Bay Gem Umphlett Goes By FRANCIS STANN * • ¦ • Star Staff Correspondent Wins at Laurel On Hitting Spree AT LEAST SOME of the baseball writers traveling with the Yankees are wondering anew and aloud if President Dan Topping is planning to unload the club in a manner similar to the way he and Co-Owner Del Webb unloaded the With Late Spurt With Five RBI s big stadium a few months ago. General Manager George Weiss, one scribe suggests, Dinner Winner Runs Tom Clouts Homer is scurrying about as if he is looking for §»pP|||HL f Paradise Along With Schmitz a fresh angel with plenty of moola. I|BP Second, Mr. Miami’s general expansion is impressive but §|| ' Third in Handicap And Roy Sievers it doesn’t extend to golf facilities and SM By Lewis F. Atchison By Burton Hawkins winter visitors are warned that in the near § j»X Star Staff Corratpandant Mp Star Staff Correspondent * future it might be wise not to bring a bag LAUREL, Md., COLUMBIA. S.C., April 3 of clubs unless they have solid connections. April 3.—Royal Senators, specializ- Bay Gem, a The surging whom come-from-behind late-inning Ben Hogan, thousands of hackers horse who hasn’t had much luck ing in rallies these 111 mV Jr days, fought five- will try to “beat” on the third annual JR this season, found a situation jk. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

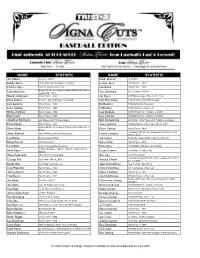

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

NEALTINE and Meat De(Lt. Chi^Roll »69 Pot Roast 3 5 5 9 6 9 '

■t W i ' r ■' V . i >'/: •/ ¥s..I' i ^OBTWmY-FOUB THURSDAY, OCTOBER 11,1966 Avaragir Daily Net PreM Run Tha Waatkar. F m - the W m V Kad#d ^attrliP0t(r lEtt^nins ISmtUt Oot a. itM ' - ■ It .e V. 8. Wi FiUr. Helen Da'vldirdn Lodge, No. M, Miss Zlisabeth Bonturl's first Miaa Jean Macfarlan, Garden u oO tm U m g Daughters .of • Scolla,'wtir hold 'a grade .won the-attendance banner Apta., Had aa weekend guests Mrs. 1 2 ,2 8 3 tonight m M tetn tia y . A bou t Tow n meeting at the Masonic Temple et the Nathan Hale PTA meeting Aghea DeRemer, her, niece and M tm h» mt tk. Avdit tonight. I.OTr S«-«a^ tomorrow night at 7:46., ' this week Instead of the fifth nephew, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Bu n m . f OUcalatiMi •a-86. ' "lly faltlj In My Job,” the lec- grade, as previously reported. ^ Hin, and Masters James and ' Pinehurst at PE^Mam.s.O aiid Friday Nights Till 9d)0 M ancheMter-—^A City o f Village Charm oa d ln • ••tie* of dlscuMion*. will Brendan Shea, son of Mr. and George Hln, all of Paterson, N. J. be belli tonight *t « o’clock in the Mrs. William J. Shea. Boulder Rd., The American . Legion ., Auxil yiMlenUon room »t Center Con- has recently been pledged to Alpha iary will meet .Monday nlghj, at 8 The legular weekly meeting of i T0fc^t.xxvf, NO. 11 , / (TWENTY PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, OCTOBER^, 1956 (ClnNlfled Advertlilng on Pago 18) PRICE. -

![Branch Rickey Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7421/branch-rickey-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-2197421.webp)

Branch Rickey Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered

Branch Rickey Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2001 Revised 2018 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms998023 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm82037820 Prepared by Connie L. Cartledge with the assistance of Paul Colton, Amy Kunze, and Susie H. Moody Expanded and revised by Connie L. Cartledge Collection Summary Title: Branch Rickey Papers Span Dates: 1890-1969 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1936-1965) ID No.: MSS37820 Creator: Rickey, Branch, 1881-1965 Extent: 29,400 items ; 87 containers ; 34.2 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Correspondence, family papers, speeches and writings, memoranda, scouting and other reports, notes, subject files, scrapbooks, and other papers, chiefly from 1936 to 1965, documenting Branch Rickey's career as a major league baseball manager and executive. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Aaron, Hank, 1934- Barber, Red, 1908- --Correspondence. Brock, Lou, 1939- Brown, Joe L.--Correspondence. Campanella, Roy, 1921-1993--Correspondence. Carey, Archibald J.--Correspondence. Carlton, Steve, 1944- Carroll, Louis F. (Louis Francis), 1905-1971--Correspondence. Clemente, Roberto, 1934-1972. Cobb, Robert H.--Correspondence. Colbert, Lester L.--Correspondence. Cooke, Jack Kent--Correspondence. Crosby, Bing, 1903-1977--Correspondence. -

Dec 11 Cover.Qxd 11/5/2020 2:39 PM Page 1 Allall Starstar Cardscards Volumevolume 2828 Issueissue #5#5

ASC080120_001_Dec 11 cover.qxd 11/5/2020 2:39 PM Page 1 AllAll StarStar CardsCards VolumeVolume 2828 IssueIssue #5#5 We are BUYING! See Page 92 for details Don’t Miss “CyberMonday” Nov. 30th!!! It’s Our Biggest Sale of theYear! (See page 7) ASC080120_001_Dec 11 cover.qxd 11/5/2020 2:39 PM Page 2 15074 Antioch Road To Order Call (800) 932-3667 Page 2 Overland Park, KS 66221 Mickey Mantle Sandy Koufax Sandy Koufax Willie Mays 1965 Topps “Clutch Home Run” #134 1955 Topps RC #123 Centered! 1955 Topps RC #123 Hot Card! 1960 Topps #200 PSA “Mint 9” $599.95 PSA “NM/MT 8” $14,999.95 PSA “NM 7” $4,999.95 PSA “NM/MT 8” Tough! $1,250.00 Lou Gehrig Mike Trout Mickey Mantle Mickey Mantle Ban Johnson Mickey Mantle 1933 DeLong #7 2009 Bowman Chrome 1952 Bowman #101 1968 Topps #280 1904 Fan Craze 1953 Bowman #59 PSA 1 $2,499.95 Rare! Auto. BGS 9 $12,500.00 PSA “Good 2” $1,999.95 PSA 8 $1,499.95 PSA 8 $899.95 PSA “VG/EX 4” $1,799.95 Johnny Bench Willie Mays Tom Brady Roger Maris Michael Jordan Willie Mays 1978 Topps #700 1962 Topps #300 2000 Skybox Impact RC 1958 Topps RC #47 ‘97-98 Ultra Star Power 1966 Topps #1 PSA 10 Low Pop! $999.95 PSA “NM 7” $999.95 Autographed $1,399.95 SGC “NM 7” $699.95 PSA 10 Tough! $599.95 PSA “NM 7” $850.00 Mike Trout Hank Aaron Hank Aaron DeShaun Watson Willie Mays Gary Carter 2011 Bowman RC #101 1954 Topps RC #128 1964 Topps #300 2017 Panini Prizm RC 1952 Bowman #218 1981 Topps #660 PSA 10 - Call PSA “VG/EX 4” $3,999.95 PSA “NM/MT 8” $875.00 PSA 10 $599.95 PSA 3MK $399.95 PSA 10 $325.00 Tough! ASC080120_001_Dec 11 cover.qxd -

Sl[[ INI ■Eph’A Cathedral, Hartford, Will Be Robbed Package Store Noon Today

/ ■ ■ -, ' ■ ‘.y ■ ' ' ' F B ID A Y .M A Y 1 , 196S A rong* Daily Ntt Prass Run P ^ E EIGHTEEN For «N Waak Caded ■fU...... V.-.-.V.. JEfirttittfl Hwalii April U, ISAS The branch office is only open for 10,952 Oecaaional Hght rain tonight. MHS Postpones Baseball Suspension Eased a period before expiration date as Biyona Photo Record Total m Cloudy, ehowen and eooL tonwpiw A b o u t T o w n Game and Track Meet a convenience for local motorists Member e( D AudH On Princess Grill vvho'Otherwise would have to. go W a ll K— p Your Bureau of dreulutleun to Hartford. Mancheater-^A Cky of VtUhge Charm '8 t. Mary’s Men's Club will hold b Identified today's scheduled CX3IL . F o r L ice n se s Procious Furs Its monthly meeting Monday^ night first place battle at Mt'. Nebo at 6;M at the church. A southern _Five days of a )5 days liquor between Manchester and Bris* VOL. LXXIL N0..181 (ClaaoMed AfiverMalag an Page M) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, MAY 2, 1953 ftiad chicken dinner will be en DeCiantis Asserts New tol High School nines was license suspension against the Kerr Notes 11,729 Re X (FOURTEEN PAGES) PRICE FIVE c u m ? joyed by the members. Princess restaurant has been ms- postponed by Coach Tom Kel ____ ______________ __________ York Man I» One Who ley and Faculty Advisor pended by the State Liquor Control newals Issued Here; > TOYS V. Rev. John J. Bennett of St. Jo- Dwight D. -

TASTE- Whether Pearson Let Any Fly Ball Fall? You Know, Like

Owls Next for Terps Roberts' Bow CLASSIFIED ADS—FEATURE PAGE—RADIO-TV—COMICS In NCAATitle Offsets Phils' flicfuming SPORTS $ Quest Big Splurges WASHINGTON, D. C., WEDNESDAY, MARCH 12, 1958 By the Auocleted Frees § The Phillies, in winning three ssp mm , JUMMya BC Victimized of their first four exhibitions, yJHHI - jhl jS are coming up with some big gmßmmmmmßmmMßMmmmmmmHmHMmmuif'<¦ West Virginia Loss • As Maryland innings, but Manager Mayo Smith is more concerned about Gains Regionals Robin Roberts. NCAA Surprise Perhaps the 31-year-old Rob- Big BY MERRELL erts, who had his WHITTLESEY worst season Otar BUS Writer in 10 years in the major leagues By the Auocleted Prea Ivy League champions, who NEW last year.'will snap back and The lineup for the week won the Garden opener from YORK, Mar. 12 end’s Maryland’s assignment become the 20-game winner of four class-packed regional play- Connecticut, 75-64. Maryland's next is far-flung NCAA against Temple, the Middle At- old. He won 20 or more games offs in the Atlantic Coast Conference for six straight seasons, 19 i HPli champion, won tournament will be champions play streaking lantic Conference in basketball will Friday’s NCAA regionals in 1956, and slumped to a 10-22 completed tonight with a pair Temple, which drew first- at *mr jppPHK a Charlotte, C., record in 1957. of games on the West Coast, round bye. in the other game N. and the Ter- rapins are playing a brand of Roberts made his first ap- but most attention still is at Charlotte. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 113 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 113 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 159 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 23, 2013 No. 8 Senate (Legislative day of Thursday, January 3, 2013) The Senate met at 9:30 a.m., on the U.S. SENATE, As Governor Adlai Stevenson said: expiration of the recess, and was called PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, Patriotism is not short, frenzied outbursts to order by the Honorable HEIDI Washington, DC, January 23, 2013. of emotion, but the tranquil and steady dedi- To the Senate: HEITKAMP, a Senator from the State of cation of a lifetime. Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, That is true. Patriotism is not short, North Dakota. of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby appoint the Honorable HEIDI HEITKAMP, a frenzied outbursts of emotion, but the PRAYER Senator from the State of North Dakota, to tranquil and steady dedication of a The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- perform the duties of the Chair. lifetime. If we look at the records, the fered the following prayer: PATRICK J. LEAHY, careers of these new Senators, that is Let us pray. President pro tempore. the way it is. Each person coming here reminds me Eternal Lord God, we shout praises Ms. HEITKAMP thereupon assumed of my first few weeks in the House of to You, for Your love never fails. You the chair as Acting President pro tem- Representatives when Tip O’Neill—we rescue us from trouble with Your lov- pore. -

2011 Baseball MG Covers

Joe Cook Dominic Favazza Bryan Penalo Mike Plakis 2011 BASEBALL 2011 Outlook . 2-3 Head Coach Fritz Hamburg . 4-5 QUICK FACTS Assistant Coaches. 6-7 The University Campbell’s Field . 8 Location . Philadelphia, Pa. 19131 2011 Roster . 9 Founded . 1851 Senio r Profiles. 10-15 Enrollment . 4,600 Junior Profiles . 16-19 Denomination . Roman Catholic (Jesuit) Sophomore Profiles . 19-22 Nickname . Hawks Newcomers. 23-25 Colors . Crimson and Gray 2010 Year in Review . 26 Athletic Affiliation . NCAA Division I 2010 Statistics . 27 Conference . Atlantic 10 Atlantic 10 Conference . 28 The Team 2010 Atlantic 10 Review . 29 Head Coach. Fritz Hamburg (Ithaca ‘89) 2011 Atlantic 10 Composite Schedule . 29 Baseball Office . 610-660-1718 Philadelphia Big 5 Baseball . 30 Career Record/Years . 34-59-1/2 years Liberty Bell Classic . 30 Record at SJU/Years . same The Hawk . 30 Assistant Coaches. Jacob Gill (Stanford ‘00) – Third season 2011 Atlantic 10 Opponents. 31 Greg Manco (Rutgers ‘92) – Seventh season 2011 Non-Conference Opponents . 32-33 Joe Tremoglie (Saint Joseph’s ‘96) – First season SJU Baseball History. 34-35 Captains . Mike Coleman, Chad Simendinger Jamie Moyer. 36 Letterwinners Returning/Lost . 20/14 2011 Hall of Fame Induction. 37 Position Starters Returning/Lost . 5/4 Starting Pitchers Returning/Lost . 4/1 SJU Baseball Hall of Fame . 38 2010 Overall Record . 18-29 Hawks in the Professional Ranks . 38 2010 Atlantic 10 Record. 13-14 Year-by-Year Results . 39 2010 Atlantic 10 Finish . T-8th All-Time Offensive Top Tens. 40 Home Field . Campbell’s Field (Camden, N.J.) All-Time Pitching Top Tens . -

Countdown to 500 Most Joyous Part of Mr

Photo credit Leo Bauby. Countdown to 500 most joyous part of Mr. Cub’s career By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Saturday, January 24, 2015 Pure joy. All the retrospectives putout immediately after Ernie Banks’ death at 83 on January 23 focus on Mr. Cub’s unbridled enthusiasm for life, mostly in the 43 years after he played his final game. What about the joy fans in Chicago and beyond took in Banks the ballplayer? Scores of Cubs rooters and others simply picked up Banks’ love of life by osmosis and ended up exulting in eve- ry career move – especially his pursuit of his 500th homer. You’d have to be a Baby Boomer at the least to remember the hoopla and countdown to Banks reaching the vaunted measurement of career power prowess. Five-hundred homers was a spec- tacular sports achievement in the mid-20th century. Only a couple of handfuls of big leaguers had reached the 500 mark by 1970: Babe Ruth, Willie Mays, Henry Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams, Mel Ott, Jimmie Foxx and Eddie Mathews. Gifted sluggers like Lou Gehrig, Stan Musial, Hank Greenberg, Ralph Kiner and Duke Snider never got to 500. It was not easy to hit a home run, and statistics were not watered down by a slew of outside factors. www.ChicagoBaseballMuseum.org [email protected] Ten years into his Hall of Fame career that began late in 1953, Banks was regarded as the Cubs’ best-ever and acquired his Mr. Cub title. He was the most beloved Cub even though by the mid- 1960s he typically ranked No.