1953 Topps, a Much Closer Look

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In, Lose, Or Draw Arcade Pontiac

SPORTS CLASSIFIED ADS P 7hl>1trttlT AvlA A A2) CLASSIFIED ADS JUNE 1951 ^t-UvIUIly JJU WEDNESDAY, 20, ** White Sox Finally Convince Yankees They re the Team to Beat I Holmes Preparing to Play About w or Draw Worrying in, Lose, as By FRANCIS STANN As Well Manage Braves DESPITE THOSE RUMORS that Billy Southworth may turn Wrong Fellows/ up with the Pirates next season, odds are that Billy is finished for keeps as a manager—just as Joe McCarthy is retired. Here were two of the best of all managers in their heydays, but they Stengel Thinks punished themselves severely. It’s odd, too, that .both careers were broken off in Boston. 60,441 Fans Thrilled They made a grim pair on the field. Maybe that’s why they were successful. McCarthy By Chicago's Rally won one pennant for the Cubs and eight for the To Split Twin Bill Yankees. Southworth won three pennants •y tha Associated Press in a row for the Cardinals, another for the Braves. When they were winning they were Those fighting White Sox ari tops' as managers. But adversity and advancing making believers of their oppo years eventually took their toll on the nervous nents—team by team, manager b; systems of these intense men. manager. McCarthy quit the Yankees in 1946 when Now it’s New York and Manage the third it became evident that, for straight Casey Stengel singing the praise to win. He sat on his year, he wasn’t going of the spectacular Sox. at Buffalo for two and was called porch years "Maybe we’ve been worryini back the Red Sox. -

LOS ANGELES DODGERS (92-52) at San Francisco Giants (57-89) LHP Clayton Kershaw (16-3, 2.15) Vs

LOS ANGELES DODGERS (92-52) at San Francisco Giants (57-89) LHP Clayton Kershaw (16-3, 2.15) vs. RHP Johnny Cueto (7-7, 4.43) Tuesday, September 12, 2017 | 7:15 p.m. PT | AT&T Park | San Francisco, CA Game 145 | Road Game 70 (40-29) | Night Game 104 (66-37) TV: KTLA/SNLA/SNLA Spanish | Radio: AM 570 (Eng.); 1020 AM (Span.) THE MIDNIGHT SPECIAL: Following last night’s marathon MATCHUP vs. GIANTS st th night at the ballpark, the Dodgers this evening continue a 10-game Dodgers: 1 , NL West (9.0 GA) Giants: 5 , NL West (36.0 GB) All-Time: LA trails series, 1,206-1,239-17 (76-87 at AT&T Park) road trip (0-1) with the second of three games against their rivals to 2017: Series tied, 7-7 (3-5 at AT&T Park) the north, the San Francisco Giants. Los Angeles has lost 11 4/24 at SF: L, 1-2 W: Cain L: Ryu S: Melancon consecutive games, which is the longest losing streak in L.A. Dodger 4/25 at SF: W, 1-2 W: Kershaw L: Blach S: Jansen history. The Dodgers have lost 16 of 17 games and five consecutive 4/26 at SF: L, 3-4 (10) W: Law L: Stripling series. Following their stay in San Francisco, the Dodgers will fly 4/27 at SF: W, 5-1 (10) W: Jansen L: Gearrin across the country to finish their road trip in Washington, D.C. (3 5/1 vs. SF: L, 3-4 W: Cueto L: Kershaw S: Law 5/2 vs. -

Nats Rushing Newsom to Mound Against Chisox

I Nats Rushing Newsom to Mound Against Chisox 4 Fifth in Row Battle of Undefeated ose or Triumph Ennis' Punch Tells for Phillies; Uline Gets Franchise Over Chicago Is Goal; Nines Bosox Maintain Lead By FRANCIS E. STANN Midget Tops Strong In Newly Formed Which Was the Best Batting Team? Hudson Foils Tribe Boys' Card Pro Court "If you were a pitcher,” asked one of the young Nats the other Loop Loop The two undefeated night, "would you rather pitch to the 1946 Red Sox or to some of those By Burton Hawkins teams In the Special Dispatch to Tha Star other like midget class of the Western Division great hitting teams, the Yankees of 1927, the Athletics of Double-O Bobo NEW Newsom, the air- of the Club of YORK, June 7.—Mike 1929 or the Yankees of 1937? I never saw any of these teams, Boys’ Washington except conditioned who was last owner the Red Sox we pia> today,” pitcher in Baseball League clash in the feature Uline, of Uline Arena in line of tomorrow’s Now there s posing a little question that could when modesty was being dis- five-game schedule. Washington, D. C., has purchased a stir a few It will be Eastern winners up arguments. If I were a pitcher I’d tributed, will establish a beachhead Quins, franchise in a new professional bas- to the Mexican of four straight, against Alexandria jump League, temporarily, any on Griffith Stadium’s ket mound to- B. undefeated in three ball league organized here yes- time these clubs came to town. -

November 13, 2010 Prices Realized

SCP Auctions Prices Realized - November 13, 2010 Internet Auction www.scpauctions.com | +1 800 350.2273 Lot # Lot Title 1 C.1910 REACH TIN LITHO BASEBALL ADVERTISING DISPLAY SIGN $7,788 2 C.1910-20 ORIGINAL ARTWORK FOR FATIMA CIGARETTES ROUND ADVERTISING SIGN $317 3 1912 WORLD CHAMPION BOSTON RED SOX PHOTOGRAPHIC DISPLAY PIECE $1,050 4 1914 "TUXEDO TOBACCO" ADVERTISING POSTER FEATURING IMAGES OF MATHEWSON, LAJOIE, TINKER AND MCGRAW $288 5 1928 "CHAMPIONS OF AL SMITH" CAMPAIGN POSTER FEATURING BABE RUTH $2,339 6 SET OF (5) LUCKY STRIKE TROLLEY CARD ADVERTISING SIGNS INCLUDING LAZZERI, GROVE, HEILMANN AND THE WANER BROTHERS $5,800 7 EXTREMELY RARE 1928 HARRY HEILMANN LUCKY STRIKE CIGARETTES LARGE ADVERTISING BANNER $18,368 8 1930'S DIZZY DEAN ADVERTISING POSTER FOR "SATURDAY'S DAILY NEWS" $240 9 1930'S DUCKY MEDWICK "GRANGER PIPE TOBACCO" ADVERTISING SIGN $178 10 1930S D&M "OLD RELIABLE" BASEBALL GLOVE ADVERTISEMENTS (3) INCLUDING COLLINS, CRITZ AND FONSECA $1,090 11 1930'S REACH BASEBALL EQUIPMENT DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $425 12 BILL TERRY COUNTERTOP AD DISPLAY FOR TWENTY GRAND CIGARETTES SIGNED "TO BARRY" - EX-HALPER $290 13 1933 GOUDEY SPORT KINGS GUM AND BIG LEAGUE GUM PROMOTIONAL STORE DISPLAY $1,199 14 1933 GOUDEY WINDOW ADVERTISING SIGN WITH BABE RUTH $3,510 15 COMPREHENSIVE 1933 TATTOO ORBIT DISPLAY INCLUDING ORIGINAL ADVERTISING, PIN, WRAPPER AND MORE $1,320 16 C.1934 DIZZY AND DAFFY DEAN BEECH-NUT ADVERTISING POSTER $2,836 17 DIZZY DEAN 1930'S "GRAPE NUTS" DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $1,024 18 PAIR OF 1934 BABE RUTH QUAKER -

Suspect Arrested After High-Speed Pursuit, Foot Chase Last Weekend's

Your Hometown Newspaper since 1949 Albany, KY 42602 - Single Copy 50¢ Thursday, March 8, 2012 Phone: 606-387-5144 - Email: [email protected] - USPS 118-480 One Section • 14 pages Between Lake Cumberland & Dale Hollow Lake Volume 62 • Number 21 Theft of City of Albany owned utility truck puts chain of events into motion Suspect arrested after high-speed pursuit, foot chase A county-wide man hunt ended peacefully Albany Police Department, Glover saw the stolen Sunday afternoon and led to the arrest of James, vehicle in the vicinity of the high school and called Easterly, 44, of Crossville, Tenn. it in to the local 911 dispatch center and began a According to Albany Police Chief Ernest pursuit. Guffey, Easterly had been passing through Albany The Clinton County Sheriff’s Department joined and could have been dropped off by another in the pursuit of the fl eeing vehicle and the suspect person. led offi cers on nearly an hour long chase that ended Unknown as to whether or not it is directly with a foot pursuit near the Teal Neathery Rd. close related, at about that same time, a report came in of to Grider Hill Dock. an attempted auto theft that had occurred at Save- A-Lot, but was unsuccessful. During the foot chase, Albany Police Offi cer Ricky Marcum came into contact with Easterly on “Someone tried to steal a vehicle at Save-A- a rock ledge near Lake Cumberland and held him Lot, but I don’t know whether it was him or not,” at gunpoint until Deputy Jim Guffey and Glover Guffey said. -

Postseaason Sta Rec Ats & Caps & Re S, Li Ecord Ne S Ds

Postseason Recaps, Line Scores, Stats & Records World Champions 1955 World Champions For the Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1955 World Series was not just a chance to win a championship, but an opportunity to avenge five previous World Series failures at the hands of their chief rivals, the New York Yankees. Even with their ace Don Newcombe on the mound, the Dodgers seemed to be doomed from the start, as three Yankee home runs set back Newcombe and the rest of the team in their opening 6-5 loss. Game 2 had the same result, as New York's southpaw Tommy Byrne held Brooklyn to five hits in a 4-2 victory. With the Series heading back to Brooklyn, Johnny Podres was given the start for Game 3. The Dodger lefty stymied the Yankees' offense over the first seven innings by allowing one run on four hits en route to an 8-3 victory. Podres gave the Dodger faithful a hint as to what lay ahead in the series with his complete-game, six-strikeout performance. Game 4 at Ebbets Field turned out to be an all-out slugfest. After falling behind early, 3-1, the Dodgers used the long ball to knot up the series. Future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella and Duke Snider each homered and Gil Hodges collected three of the club’s 14 hits, including a home run in the 8-5 triumph. Snider's third and fourth home runs of the Series provided the support needed for rookie Roger Craig and the Dodgers took Game 5 by a score of 5-3. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1945-04-11

1945 • - --== IIIEAT!!, PATS, ,ed II.mpa, TI Ihroo,h U 18' A! I./I,ou,' I·~ n.. 'u.... .aOCE88ED rooDs, bl .. ..mp., C~ 111, ..,11 XI ....... (lUGAa, b.ok f ..,. ••• ." " n .... , •• II.. ........ IIHO&', ••• ~ """ Cloudy, ity ....... I, I .D' a'.... ,... 11011017. GASOLINE, 15-A ~''''.D' ,1041 t.r toa, ,aU •••••• a .... , 8·'1 C.... aD. Co, ••1111 ,., II.. ..nODI. J'UIiL OIL. p.rl... ODO IOWA: ParUy cloud,T and &br ••,b flv. CG.pID. • •••, allo la,. y •••-'. ,erlo. THE DAILY IOWAN windy. Continued WanDo. ,.... 18' II•• roo'. Iowa CItY'1 Morning Uewlpaper eel FIVE CENTS 'I''' A.IOO1A'I'U ...... IOWA CITY, IOWA WEDNESDAY. APRU. II. 1945 VOLUME XXI NUMBER 168 township the Blue recenuy n .COUnty )mght at annover Fa s to • • iht rmy I hotel. heir sup. I entitled German Frontline News Hints- YANKS SEE OWN HANDIWORK will be Soviets Jab · . Yanks (ripple ,- Yank Drive , direclor II service End of Or9on__i_ze_d_W_' a_rf_o_re__ Nea_ r Luftwaffe Moines To Cut Vienna Now 110 Miles benefl~ prisoners allied taken in the last for a junction with allied torces By Klrke L. SlmPllOn two weeks lell small doubt of what Associated Press War Analyst at the Elbe Is launched. Berlin has I H R 'd au memo most of their comrades would do. illsisted for weeks it was impend- n, uge al Lee Nit. Escape Route, There are broad hints in front "Those still wi Uing to die for ing if not in progress but without From Berlin n Rarick line news from Germany that the tuehrer are few and tar be confirmation from Moscow. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Prices Realized

SPRING 2014 PREMIER AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot# Title Final Price 1 C.1850'S LEMON PEEL STYLE BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $2,421.60 2 1880'S FIGURE EIGHT STYLE BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $576.00 3 C.1910 BASEBALL STITCHING MACHINE (NSM COLLECTION) $356.40 4 HONUS WAGNER SINGLE SIGNED BASEBALL W/ "FORMER PIRATE" NOTATION (NSM COLLECTION) $1,934.40 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO JUNE 30TH, 1909 FORBES FIELD (PITTSBURGH) OPENING GAME AND 5 DEDICATION CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $7,198.80 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO JUNE 30TH, 1910 FORBES FIELD OPENING GAME AND 1909 WORLD 6 CHAMPIONSHIP FLAG RAISING CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $1,065.60 1911 CHICAGO CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES (WHITE SOX VS. CUBS) PRESS TICKET AND SCORERS BADGE AND 1911 COMISKEY 7 PARK PASS (NSM COLLECTION) $290.40 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO MAY 16TH, 1912 FENWAY PARK (BOSTON) OPENING GAME AND DEDICATION 8 CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $10,766.40 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO APRIL 18TH, 1912 NAVIN FIELD (DETROIT) OPENING GAME AND DEDICATION 9 CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $1,837.20 ORIGINAL INVITATION TO AUGUST 18TH, 1915 BRAVES FIELD (BOSTON) OPENING GAME AND 1914 WORLD 10 CHAMPIONSHIP FLAG RAISING CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $939.60 LOT OF (12) 1909-1926 BASEBALL WRITERS ASSOCIATION (BBWAA) PRESS PASSES INCL. 6 SIGNED BY WILLIAM VEECK, 11 SR. (NSM COLLECTION) $580.80 12 C.1918 TY COBB AND HUGH JENNINGS DUAL SIGNED OAL (JOHNSON) BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $11,042.40 13 CY YOUNG SINGLE SIGNED BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $42,955.20 1929 CHICAGO CUBS MULTI-SIGNED BASEBALL INCL. ROGERS HORNSBY, HACK WILSON, AND KI KI CUYLER (NSM 14 COLLECTION) $528.00 PHILADELPHIA A'S GREATS; CONNIE MACK, CHIEF BENDER, EARNSHAW, EHMKE AND DYKES SIGNED OAL (HARRIDGE) 15 BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $853.20 16 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED 1948 FIRST EDITION COPY OF "THE BABE RUTH STORY" (NSM COLLECTION) $7,918.80 17 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $15,051.60 18 DIZZY DEAN SINGLE SIGNED BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $1,272.00 1944 & 1946 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ST. -

Inside Center Opens New Tower This Issue

The Weekly Newspaper of Torrance Herald Publications - Torrance, El Segundo, Manhattan Beach, Hawthorne, Lawndale, & Inglewood Community Newspapers Since 1911 - (310) 322-1830 - Vol. 4, No. 39 - September 25, 2014 Torrance Memorial Medical Inside Center Opens New Tower This Issue Calendar...............................3 Certified & Licensed Professionals ....................10 Classifieds ...........................4 Crossword/Sudoku ............4 Food ......................................5 Legals ...................................9 Pets .....................................11 Actors portraying Torrance Memorial founders Jared Sidney Torrance and Helena Childs Torrance with Torrance Memorial nurses dressed in 1920s uniforms and members of the Torrance Fire Department Police Reports ....................3 in front of a Ford Model A, at the grand opening celebration of the new Melanie and Richard Lundquist Tower. See more photos, page 2. Photo credit: Diedre Davidson. Politically Speaking ...........7 Herring and Tsao Join City Real Estate. .......................12 Council Planning Commission By Dylan Little for the entire Council. He encouraged all assessed value of their property. Measure T The Torrance City Council selected Milton the candidates to try again in January when will be used to update facilities and equipment Sports ...................................6 Herring and Richard Tsao to fill the vacancies the Council will be selecting commissioners to accommodate advanced courses in math, on the city’s Planning Commission during for all the city’s various committees. “This science and technology, improve the energy their September 23 meeting. While normally was a very difficult one,” said Furey. “There and water efficiency of the district’s schools, commissioners are appointed in January, these were only two positions open and we had provide safety infrastructure and disaster two commissioners will be replacing two that ten very well qualified candidates. -

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Media Relations Phone: (718) 579-4460 • [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2012 (Postseason) 2012 AMERICAN LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES – GAME 1 Home Record: . 51-30 (2-1) NEW YORK YANKEES (3-2/95-67) vs. DETROIT TIGERS (3-2/88-74) Road Record: . 44-37 (1-1) Day Record: . .. 32-20 (---) LHP ANDY PETTITTE (0-1, 3.86) VS. RHP DOUG FISTER (0-0, 2.57) Night Record: . 63-47 (3-2) Saturday, OctOber 13 • 8:07 p.m. et • tbS • yankee Stadium vs . AL East . 41-31 (3-2) vs . AL Central . 21-16 (---) vs . AL West . 20-15 (---) AT A GLANCE: The Yankees will play Game 1 of the 2012 American League Championship Series vs . the Detroit Tigers tonight at Yankee Stadium…marks the Yankees’ 15th ALCS YANKEES IN THE ALCS vs . National League . 13-5 (---) (Home Games in Bold) vs . RH starters . 58-43 (3-0) all-time, going 11-3 in the series, including a 7-2 mark in their last nine since 1996 – which vs . LH starters . 37-24 (0-2) have been a “best of seven” format…is their third ALCS in five years under Joe Girardi (also YEAR OPP W L Detail Yankees Score First: . 59-27 (2-1) 2009 and ‘10)…are 34-14 in 48 “best-of-seven” series all time . 1976** . KC . 3 . 2 . WLWLW Opp . Score First: . 36-40 (1-1) This series is a rematch of the 2011 ALDS, which the Tigers won in five games . -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

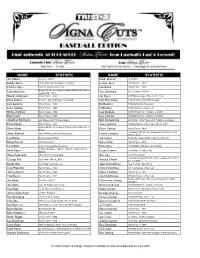

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank