By Joel Cohen & Bennett L. Gershman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hank-Aaron.Pdf

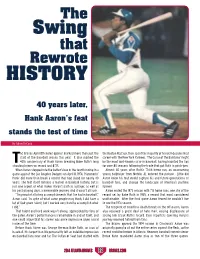

The Swing that Rewrote HISTORY 40 years later, Hank Aaron’s feat stands the test of time By Adam DeCock he Braves April 8th home opener marked more than just the the Boston Red Sox, then spent the majority of his well-documented start of the baseball season this year. It also marked the career with the New York Yankees. ‘The Curse of the Bambino’ might 40th anniversary of Hank Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s long be the most well-known curse in baseball, having haunted the Sox standing home run record and #715. for over 80 seasons following the trade that put Ruth in pinstripes. When Aaron stepped into the batter’s box in the fourth inning in a Almost 40 years after Ruth’s 714th home run, an unassuming game against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974, ‘Hammerin’ young ballplayer from Mobile, AL entered the picture. Little did Hank’ did more than break a record that had stood for nearly 40 Aaron know his feat would capture his and future generations of years. The feat itself remains a marvel in baseball history, but is baseball fans, and change the landscape of America’s pastime just one aspect of what makes Aaron’s path as a player, as well as forever. his post-playing days, a memorable journey. And it wasn’t all luck. Aaron ended the 1973 season with 713 home runs, one shy of the “I’m proud of all of my accomplishments that I’ve had in baseball,” record set by Babe Ruth in 1935, a record that most considered Aaron said. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

New Ordinance Notice

7/1/2015 ARTICLE 19O: [BAN ON SMOKELESS TOBACCO USE] Print San Francisco Health Code ARTICLE 19O: [BAN ON SMOKELESS TOBACCO USE] New Ordinance Notice Publisher's Note:This Article has been ADDED by new legislation (Ord. 5915 , approved 5/8/2015, effective 6/7/2015, operative 1/1/2016). Although not yet operative, the text of the Article and its constituent sections is included below for the convenience of the Code user. Sec. 19O.1. Findings. Sec. 19O.2. Definitions. Sec. 19O.3. Prohibiting the Use of Tobacco Products at Athletic Venues. Sec. 19O.4. Rules and Regulations. Sec. 19O.5. Enforcement. Sec. 19O.6. Signs. Sec. 19O.7. Preemption. Sec. 19O.8. Severability. Sec. 19O.9. Undertaking for the General Welfare. Sec. 19O.10. Operative Date. SEC. 19O.1. FINDINGS. Public health authorities, including the Surgeon General and the National Cancer Institute, have found that smokeless tobacco use is hazardous to health and can easily lead to nicotine addiction. The National Cancer Institute states that chewing tobacco and snuff contain 28 cancercausing agents and the U.S. National Toxicology Program has established smokeless tobacco as a "known human carcinogen." The National Cancer Institute and the International Agency for Research on Cancer report that use of smokeless tobacco causes oral, pancreatic, and esophageal cancer; and may also cause heart disease, gum disease, and oral lesions other than cancer, such as leukoplakia (precancerous white patches in the mouth). Youth participation in sports has many health benefits including the development of positive fitness habits, reducing obesity, and combating the epidemic of early onset diabetes. -

Mckay Spr2013 Pdf (487.1Kb)

University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Department of History The Triple Play Twentieth Century Representation of Baseball in Wisconsin Jacqueline McKay Advising Professor: Jane Pederson Spring 2013 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version in published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire with the consent of the author. i Abstract Wisconsin has a rich history rooted in immigrants, industry, and sporting culture, all of which played a role in the history of baseball. Baseball's history throughout the state has changed because of major historic events but also with the guided assistance of three memorable men. The role Raymond Gillette, Henry Aaron, and Allen Selig played in the history of Wisconsin's story in the sport of baseball gives it a unique past, and rare evolution of the game unmatched by other states. Following the story of these men and the shift in baseball's importance during World War II, Wisconsin's story of baseball has changed from being a part of industrial worker culture, to the sport as a major industry itself. Each of these men has provided a different aspect of the sport and their importance is equal, yet unmatched. ii Acknowledgment I would like to thank my professor Dr. Jane Pederson as well as Erin Devlin, my mentor on the project. Without their guidance and support with the paper I would have had a much more difficult, and less enjoyable experience. I would also like to thank Raymond Gillette, Henry Aaron, and Allen Selig for the tremendous effect that have had on baseball in the state of Wisconsin, and although I do not have the resources or connections to thank them personally, their impact is what made this project possible. -

Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2011-09-23 Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era Kevin R. Nielsen Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Nielsen, Kevin R., "Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 2876. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2876 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fans don't boo nobodies: Image repair strategies of high-profile baseball players during the Steroid Era Kevin Nielsen A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Steve Thomsen, Chair Kenneth Plowman Tom Robinson Department of Communications Brigham Young University December 2011 Copyright © 2011 Kevin Nielsen All Rights Reserved Fans don't boo nobodies: Image repair strategies of high-profile baseball players during the Steroid Era Kevin Nielsen Department of Communications, BYU Master of Arts Baseball's Steroid Era put many different high-profile athletes under pressure to explain steroid allegations that were made against them. This thesis used textual analysis of news reports and media portrayals of the athletes, along with analysis of their image repair strategies to combat those allegations, to determine how successful the athletes were in changing public opinion as evidenced through the media. -

Chicago Tribune: Baseball World Lauds Jerome

Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman -- chicagotribune.com Page 1 of 3 www.chicagotribune.com/sports/chi-22-holtzman-baseballjul22,0,5941045.story chicagotribune.com Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman Ex-players, managers, officials laud Holtzman By Dave van Dyck Chicago Tribune reporter July 22, 2008 Chicago lost its most celebrated chronicler of the national pastime with the passing of Jerome Holtzman, and all of baseball lost an icon who so graciously linked its generations. Holtzman, the former Tribune and Sun-Times writer and later MLB's official historian, indeed belonged to the entire baseball world. He seemed to know everyone in the game while simultaneously knowing everything about the game. Praise poured in from around the country for the Hall of Famer, from management and union, managers and players. "Those of us who knew him and worked with him will always remember his good humor, his fairness and his love for baseball," Commissioner Bud Selig said. "He was a very good friend of mine throughout my career in the game and I will miss his friendship and counsel. I extend my deepest sympathies to his wife, Marilyn, to his children and to his many friends." The men who sat across from Selig during labor negotiations—a fairly new wrinkle in the game that Holtzman became an expert at covering—remembered him just as fondly. "I saw Jerry at Cooperstown a few years ago and we talked old times well into the night," said Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the Players Association. "We always had a good relationship. He was a careful writer and, covering a subject matter he was not familiar with, he did a remarkably good job." "You don't develop the reputation he had by accident," said present-day union boss Donald Fehr. -

AUCTION ITEMS FSCNY 18 Annual Conference & Exposition May 11

AUCTION ITEMS FSCNY 18th Annual Conference & Exposition May 11, 2010 These items will be available for auction at the Scholarship booth at FSCNY's Conference & Exposition on May 11th. There will be more baseball items added as we get closer to the conference. All proceeds will go to the FSCNY Scholarship Program. Payment can be made by either a check or credit card. Your continued support is greatly appreciated. Sandy Herman Chairman, Scholarship Committee Baseball Robinson Cano Autographed Baseball Bat - Autographed baseball bat of Yankees Robinson Cano. Bucky Dent and Mike Torrez Autographed Framed Photo - A photo of Bucky Dent's homerun over the green monster in 1978, autographed by Bucky Dent and Mike Torrez. Derek Jeter SI Cover/WS Celebration Collage with Plaque - Original 8x10 photo of SI cover with Derek Jeter Sportsman of the year next to original 8x10 photo of Derek Jeter during locker room celebration after World Series win. Derek Jeter Autographed Baseball - Baseball autographed photo of Yankees Derek Jeter. Derek Jeter Autographed 16x20 Framed Photo - Sepia autographed photo of Yankees Derek Jeter tapping the DiMaggio Quote sign that says I want to Thank the Good Lord for Making me a Yankee. It is also signed by the artist. Derek Jeter 20x24 Photo with Dirt from the Stadium (Sliding into 3rd) - Photo of Derek Jeter sliding dirt from the stadium affixed to the photo. Derek Jeter Framed Photo/Ticket/Scorecard Collage (Record Breaking Hit) - This is a photo of Derek Jeter as he set the all time Yankee hit record with framed with a replica of the ticket and scorecard from the game Jerry Koosman, Ed Charles and Jerry Grote Autographed 8x10 Framed Photo - Autographed photo of Jerry Grote, Ed Charles, and Jerry Koosman at the moment the Mets won the 1969 World Series. -

Multitasking Creates Mediocrity and Mistakes April 26, 2009

Bob Behn’s Performance Leadership Report An occasional (and maybe even insightful) examination of the issues, dilemmas, challenges, and opportunities for improving performance and producing real results in public agencies. Vol. 9, No. 8, April 2011 On why all public executives need to be aware of how Copyright © 2011 by Robert D. Behn Multitasking Creates Mediocrity and Mistakes April 26, 2009. Fenway Park. Bos- Indeed, during 2011, Ellsbury and multiple, simultaneous tasks that ton Red Sox vs. New York Yankees. Crawford are going to be exhibit A & involve thinking and deciding. These Bottom of the fifth inning. Bases B (or B & A) for the problem of multi- tasks require the brain to reset be- loaded. Andy Pettitte pitching for the tasking. And just wait until Ellsbury tween each thought—between each Yankees. Jacoby Ellsbury, Boston’s is on third and Crawford is on first. choice. This creates a lag. And if the fastest player, on third base. But We humans believe, of course, brain is trying to go back and forth Pettitte isn’t paying attention. that we are excellent at multitasking. between two different tasks, these Ellsbury steals home. Just ask us. In fact, however, people lags begin to accumulate (though to Andy Pettitte may not think so, but who report that they are excellent these lags, we humans are completely to Judy and me, cheering from the multitaskers are easily distracted. oblivious). bleachers, this is baseball at its best. “High multitaskers are suckers for Some types of multitasking are In four seasons with the Red Sox, irrelevancy,” concluded Clifford Nass easy. -

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Media Relations Phone: (718) 579-4460 • [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2012 (Postseason) 2012 AMERICAN LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES – GAME 1 Home Record: . 51-30 (2-1) NEW YORK YANKEES (3-2/95-67) vs. DETROIT TIGERS (3-2/88-74) Road Record: . 44-37 (1-1) Day Record: . .. 32-20 (---) LHP ANDY PETTITTE (0-1, 3.86) VS. RHP DOUG FISTER (0-0, 2.57) Night Record: . 63-47 (3-2) Saturday, OctOber 13 • 8:07 p.m. et • tbS • yankee Stadium vs . AL East . 41-31 (3-2) vs . AL Central . 21-16 (---) vs . AL West . 20-15 (---) AT A GLANCE: The Yankees will play Game 1 of the 2012 American League Championship Series vs . the Detroit Tigers tonight at Yankee Stadium…marks the Yankees’ 15th ALCS YANKEES IN THE ALCS vs . National League . 13-5 (---) (Home Games in Bold) vs . RH starters . 58-43 (3-0) all-time, going 11-3 in the series, including a 7-2 mark in their last nine since 1996 – which vs . LH starters . 37-24 (0-2) have been a “best of seven” format…is their third ALCS in five years under Joe Girardi (also YEAR OPP W L Detail Yankees Score First: . 59-27 (2-1) 2009 and ‘10)…are 34-14 in 48 “best-of-seven” series all time . 1976** . KC . 3 . 2 . WLWLW Opp . Score First: . 36-40 (1-1) This series is a rematch of the 2011 ALDS, which the Tigers won in five games . -

Smith Writes Off Failed HOF Bid in Final Year of Eligibility on Ballot

Smith writes off failed HOF bid in final year of eligibility on writers’ ballot By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Wednesday, January 18, 2017 The announcement hardly came as a shock to Lee Arthur Smith when the Chicago Baseball Museum called the for- mer Cubs closer with bad news a few minutes after the Jan. 18 Hall of Fame vote was announced. “I think I’m just going to write it off,” Smith said of fall- ing short of induction in his 15th and final year of eligibil- ity on the Baseball Writers Association of America ballot- ing. Now Smith is remanded to whatever latter-day name the old Veterans Committee takes. And that panel only meets every three years to consider the late 20th century period group in which Smith pitched. “Maybe if the veterans thing comes around, but I don’t Lee Smith knew he'd fall short think I’ll be paying too much attention,” said a philo- in Hall of Fame voting. sophical Smith. One man’s meat always is another man’s poison in Hall of Fame voting. Tim Raines, with two distinguished tenures as a White Sox player and coach, is going in with Jeff Bagwell and Ivan Rodriguez. Meanwhile, Smith has to take his proverbial glove and ball, and go home even after ranking as the all-time saves leader not long ago. Smith, working for many years as the Giants’ roving minor-league pitching instructor, has long stopped rationalizing the voting process in which he started off relatively strong, then lost ground through recent years. -

October 21, 2020 Bulletin

ROTARY NOTES A publication of the Rotary Club of Warren Nearly 1.4 billion people live on less than $1.25 a day. Rotarians help promote economic development & reduce poverty Rotary Motto in underserved communities by Service Above expanding vocational training Self opportunities, creating well-paying jobs, supporting small businesses, & providing access to financial 4-Way Test management institutions. Through Of the things we service projects, they work to strengthen local entrepreneurs & community think, say or do: leaders and grow economies locally & around the word. Is it the truth? Is it fair to all October 21, 2020 concerned? Will it build ASSIGNMENTS goodwill and better GREETERS friendship? 10/28/2020 – Keno Hills 11/4/2020 – Lauren Kramer Will it be beneficial to all concerned? INVOCATION October, 2020 – Andy Bednar Avenues of November, 2020 – Lisa Taddei Service FELLOWSHIP Club Service October, 2020 – Ted Stazak Vocational November, 2020 – Christine Cope Service MAGAZINE REPORT Community October, 2020 – Denise May Service November, 2020 – Diane Sauer International Service SPEAKERS 10/28/2020 – Larry Woods, Candidate for Coroner Youth Service 11/4/2020 – Mike Bollas will speak about American Presidents who were Veterans Areas of Focus Promoting Peace Fighting Disease Providing Clean Water Following our traditional opening ceremonies, including a zippy rendition of Saving Mothers “The 4-Way Test” song, Ted Stazak led & Children st us through a history lesson on October 21 . Supporting Education Swedish Chemist, Engineer and The FouTest” Innovator, Alfred Nobel, was born on Growing Local October 21, 1883 in Stockholm, Sweden. Economies Nobel was the inventor of dynamite. He also owned Bofors, which he had redirected Club Officers from its previous role as primarily an iron President and steel producer to a major manufacturer Dominic of cannon and other armaments. -

Outside the Lines

Outside the Lines Vol. V, No. 2 SABR Business of Baseball Committee Newsletter Spring 1999 Copyright © 1999 Society for American Baseball Research Editor: Doug Pappas, 100 E. Hartsdale Ave., #6EE, Hartsdale, NY 10530-3244, 914-472-7954. E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected]. Chairman’s Letter See you in Scottsdale. Make plans to attend SABR’s 29th annual convention, June 24-27, at the Radisson Resort in sunny Scottsdale, Arizona. And try to get there early: the Busienss of Baseball Committee’s annual meeting will be held Thursday afternoon, June 24, from 3:00-4:00 p.m. We’re scheduled opposite Baseball Records and just before Ballparks and Retrosheet.) Last issue’s discussion of the large market/small market issue ran so long that I’ve got six months of news updates to present...so on with the show! MLB News Luxury tax bills paid. After posting a 79-83 record with the majors’ highest payroll, the Baltimore Orioles were hit with a $3,138,621 luxury tax bill for the 1998 season. Other taxpayers included the Red Sox ($2,184,734), Yankees ($684,390), Braves ($495,625) and Dodgers ($49,593). The tax threshold, originally expected to reach $55 million in 1998, actually leaped to $70,501,185, including $5,576,415 per team in benefits. This figure represents the midpoint between the fifth- and sixth-highest payrolls. The luxury tax rate falls from 35% to 34% in 1999, then disappears entirely in 2000. Owners go 9-2 in arbitration. Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera of the Yankees were the only players to win their arbitration hearings, although 51 of the 62 cases settled before a ruling.