Yakima River Basin Integrated Water Resource Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington by Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein

Prepared in Cooperation with the Water Resources Program of the Yakama Nation Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington By Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3315 Photograph showing Mount Adams andesitic stratovolcano and Signal Peak mafic shield volcano viewed westward from near Mill Creek Guard Station. Low-relief rocky meadows and modest forested ridges marked by scattered cinder cones and shields are common landforms in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field. Mount Adams (elevation: 12,276 ft; 3,742 m) is centered 50 km west and 2.8 km higher than foreground meadow (elevation: 2,950 ft.; 900 m); its eruptions began ~520 ka, its upper cone was built in late Pleistocene, and several eruptions have taken place in the Holocene. Signal Peak (elevation: 5,100 ft; 1,555 m), 20 km west of camera, is one of largest and highest eruptive centers in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field; short-lived shield, built around 3.7 Ma, is seven times older than Mount Adams. 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Introductory Overview for Non-Geologists ...............................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................2 Physiography, Environment, Boundary Surveys, and Access ......................................................6 Previous Geologic -

Indian Artifacts of the Columbia River Priest

IINNDDIIAANN AARRTTIIFFAACCTTSS OOFF TTHHEE CCOOLLUUMMBBIIAA RRIIVVEERR PPRRIIEESSTT RRAAPPIIDDSS TTOO TTHHEE CCOOLLUUMMBBIIAA RRIIVVEERR GGOORRGGEE IIIDDDEEENNNTTTIIIFFFIIICCCAAATTTIIIOOONNN GGGUUUIIIDDDEEE VVVOOOLLLUUUMMMEEE 111 DDDaaavvviiiddd HHHeeeaaattthhh Copyright 2003 All rights reserved. This publication may only be reproduced for personal and educational use. SSSCCCOOOPPPEEE This document is used to define projectile point typologies common to the Columbia Plateau, covering the region from Priest Rapids to the Columbia Gorge. When employed, recognition of a specified typology is understood as define within the body of this document. This document does not intend to cover, describe or define all typologies found within the region. This document will present several recognized typologies from the region. In several cases, a typology may extend beyond the Columbia Plateau region. Definitions are based upon research and records derived from consultation with; and information obtained from collectors and authorities. They are subject to revision as further experience and investigation may show is necessary or desirable. This document is authorized for distribution in an electronic format through selected organizations. This document is free for personal and educational use. RRREEECCCOOOGGGNNNIIITTTIIIOOONNN A special thanks for contributions given to: Ben Stermer - Technical Contributions Bill Jackson - Technical Contributions Joel Castanza - Images Mark Berreth - Images, Technical Contributions Randy McNeice - Images Rodney Michel -

Chapter 11. Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit Yakima River Basin Critical Habitat Unit

Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification: Rationale for Why Habitat is Essential, and Documentation of Occupancy Chapter 11. Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit Yakima River Basin Critical Habitat Unit 353 Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification Chapter 11 U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service September 2010 Chapter 11. Yakima River Basin Critical Habitat Unit The Yakima River CHU supports adfluvial, fluvial, and resident life history forms of bull trout. This CHU includes the mainstem Yakima River and tributaries from its confluence with the Columbia River upstream from the mouth of the Columbia River upstream to its headwaters at the crest of the Cascade Range. The Yakima River CHU is located on the eastern slopes of the Cascade Range in south-central Washington and encompasses the entire Yakima River basin located between the Klickitat and Wenatchee Basins. The Yakima River basin is one of the largest basins in the state of Washington; it drains southeast into the Columbia River near the town of Richland, Washington. The basin occupies most of Yakima and Kittitas Counties, about half of Benton County, and a small portion of Klickitat County. This CHU does not contain any subunits because it supports one core area. A total of 1,177.2 km (731.5 mi) of stream habitat and 6,285.2 ha (15,531.0 ac) of lake and reservoir surface area in this CHU are proposed as critical habitat. One of the largest populations of bull trout (South Fork Tieton River population) in central Washington is located above the Tieton Dam and supports the core area. -

Suggested Fishing Destinations in Central Washington the Yakima

Suggested Fishing Destinations in Central Washington Always refer to the WDFW Fishing Regulation Pamphlet prior to fishing any of these streams. Most of these are within an easy drive of Red’s Fly Shop, or even a day trip from the Puget Sound area. The east slopes of the Cascades are regarded as the best small stream fishing in Washington State and a GREAT place to start as a beginner! Most of the fisheries here offer small trout in abundance, which is great adventure and perfect for learning the art of fly fishing. The Yakima River Canyon The Canyon near Red’s Fly Shop is best wade fished when the river flows are below 2,500 cfs. September and October are the best months for wading, but February and March can offer great bank access as well. Spring and summer are more challenging but still possible. Yakima County Naches River – Trout tend to be most abundant upstream from the Tieton River junction. The best wade fishing season is July – October Tieton River – It runs fairly dirty in June, but July – mid August is excellent. Rattlesnake Creek – This is a great hike in adventure and offers wonderful small stream Cutthroat fishing for anyone willing to get off the beaten path. Little Naches River – Easy access off of USFS Road 19, July – October is the best time. American River/Bumping Rivers – These are in the headwaters of the Naches drainage. Be sure to read the WDFW Regulations if you fish the American River. Ahtanum Creek – Great small stream fishing. June – October Wenas Creek – Small water, small fish, but a great adventure. -

Concentrations of Nitrate in Drinking Water in the Lower Yakima River Basin, Groundwater Management Area, Yakima County, Washington, 2017

Prepared in cooperation with Yakima County, Washington, for the Lower Yakima River Basin Groundwater Management Area Concentrations of Nitrate in Drinking Water in the Lower Yakima River Basin, Groundwater Management Area, Yakima County, Washington, 2017 Data Series 1084 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Yakama area drain site, Yakima River at Umantum, Washington (12484500), December 18, 2012. Photograph by Gabe Landrum, U.S. Geological Survey. Concentrations of Nitrate in Drinking Water in the Lower Yakima River Basin, Groundwater Management Area, Yakima County, Washington, 2017 By Raegan L. Huffman Prepared in cooperation with Yakima County, Washington, for the Lower Yakima River Basin Groundwater Management Area Data Series 1084 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Huffman, R.L., 2018, Concentrations of nitrate in drinking water in the lower Yakima River Basin, Groundwater Management Area, Yakima County, Washington, 2017: U.S. -

Chapter 4. Yakima River Flooding Characteristics

CHAPTER 4. YAKIMA RIVER FLOODING CHARACTERISTICS Flooding is common in Yakima County. Since 1894, the flow in the Yakima River has exceeded flood stage 48 times. Yakima County has been declared a federal disaster area eight times since 1970, most recently in 1990, 1995, 1996 and 1997. However, historical flood events and associated damage are often forgotten over time. Extended mild weather or construction of flood control facilities can provide a false sense of security. Floodplain residents should realize that neither the construction of flood-control facilities nor the lack of recent flood damage guarantees safety from future flood damage. Lessons learned from past floods should not be forgotten; flooding will occur again and it could be worse than even the most severe historical floods. COMMON FLOOD CHARACTERISTICS A variety of flood characteristics determine the extent of flood damage within Yakima County. Some flood problems are obvious, such as damage to homes and inundation of farmland. However, many other flood problems are less obvious or are indirect results of flooding: forced evacuations, erosion and loss of property, contaminated water supplies, diversion of public resources, loss of public utilities and facilities, etc. Together, these problems cost property owners and taxpayers money (whether they live in the floodplain or not), disrupt lives and commerce, and burden governments with continual maintenance and emergency services problems. Flood problems are typically addressed by modifying historical flooding patterns. For example, floodwater inundation can be addressed by confining flood flows between levees to change floodplain conveyance and storage capacity. However, modifying one flooding pattern generally results in negative effects elsewhere. -

Washington Geology

WASHINGTON VOL. 29, NO. 3/4 DECEMBER 2001 RESOURCES GEOLOGY NATURAL IN THIS ISSUE z A division in transition, p. 2 z 1998 debris flows near the Yakima River, p. 3 z Dating the Bonneville landslide with lichenometry, p. 11 z Skolithos in a quartzite cobble from Lopez Island, p. 17 z Port Townsend’s marine science center expands, p. 20 z Earth Connections, p. 22 z Get your geology license now—Don’t procrastinate, p. 24 WASHINGTON A Division in Transition GEOLOGY Ronald F. Teissere, State Geologist Vol. 29, No. 3/4 Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources December 2001 PO Box 47007; Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Washington Geology (ISSN 1058-2134) is published four times a year in print and on the web by the Washington State Department of Natural y introductory column as the State Geologist focuses on Resources, Division of Geology and Earth Resources. Subscriptions are Mtransition. The new management team of the Division of free upon request. The Division also publishes bulletins, information cir- Geology and Earth Resources is described elsewhere in this is- culars, reports of investigations, geologic maps, and open-file reports. A sue. The Division is facing significant challenges and opportu- publications list is posted on our website or will be sent upon request. nities because of changing circumstances on two fronts: fund- ing and technology. The decade of the 1990s was a period of DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES exceptional economic growth. During the same period, fund- Ronald F. Teissere, State Geologist ing for the natural resource agencies in Washington from the David K. -

Yakima River Basin Study

Yakima River Basin Study Yakima River Basin Water Resources Technical Memorandum U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Contract No. 08CA10677A ID/IQ, Task 1 Prepared by Anchor QEA U.S. Department of the Interior State of Washington Bureau of Reclamation Department of Ecology Pacific Northwest Region Office of Columbia River March 2011 Columbia-Cascades Area Office MISSION STATEMENTS The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. The Mission of the Washington State Department of Ecology is to protect, preserve and enhance Washington’s environment, and promote the wise management of our air, land and water for the benefit of current and future generations. Yakima River Basin Study Yakima River Basin Water Resources Technical Memorandum U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Contract No. 08CA10677A ID/IQ, Task 1 Prepared by Anchor QEA U.S. Department of the Interior State of Washington Bureau of Reclamation Department of Ecology Pacific Northwest Region Office of Columbia River March 2011 Columbia-Cascades Area Office This Page Intentionally Left Blank Contents 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Yakima River -

30 Day Notice of Availability – Draft Integrated Detailed Project Report and Environmental Assessment

30 Day Notice of Availability – Draft Integrated Detailed Project Report and Environmental Assessment Environmental & Cultural Resources Branch Public Notice Date: March 27, 2017 P.O. Box 3755 Expiration Date: April 26, 2017 Seattle, WA 98124-3755 Reference: PM-ER-17-03 ATTN: Melissa Leslie Name: Yakima River Gap to Gap Ecosystem Restoration Project Interested parties are hereby notified that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District (Corps) has prepared, pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act, a draft Integrated Detailed Project Report and Environmental Assessment (DPR/EA) for the Yakima River Gap to Gap Ecosystem Restoration Project. Located east of the Cascade Mountain Range in central Washington State, the Yakima River ecosystem between the cities of Yakima and Union Gap has been degraded and reduced over time as a result of infrastructure and urban development. Environmental impacts and degradation can be tied directly to the Congressionally Authorized Yakima Levee System built by the Corps beginning in 1947. The federal levee system includes approximately five miles of levee along the right bank and two miles of levee along the left bank of the Yakima River. In addition, local and federal entities over time have extended the original Corps system to include several additional miles of levee both upstream and downstream of the original authorized project. The purpose of this Public Notice is to solicit comments from interested persons, groups, and agencies. A copy of the draft DPR/EA is available on the Seattle District Corps website under the project title Yakima River Gap to Gap Ecosystem Restoration Project: http://www.nws.usace.army.mil/Missions/Environmental/Environmental-Documents/ AUTHORITY The proposed project falls under the Authority of Section 1135 of the Water Resources and Development Act of 1986, as amended (Section 1135). -

PLAN of STUDY for the YAKIMA RIVER BASIN WETLANDS, RIPARIAN, and FLOODPLAIN HABITAT PLAN

PLAN OF STUDY for the YAKIMA RIVER BASIN WETLANDS, RIPARIAN, AND FLOODPLAIN HABITAT PLAN December 1998 EXTERNAL REVIEW TEAM Member Agency Dave Kaumhimer, Leader Bureau of Reclamation Brent Renfrow Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Kathy Reed Washington Department of Ecology Don Haley US Fish and Wildlife Service Pat Monk Yakima River Board of Joint Control Tracy Hames Yakama Nation Tom Ring Yakama Nation Figure 1.-Yakima River Basin Subareas (General Locations) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 BASIN CONSERVATION PLAN ............................................................................................ 2 1.2.1 Yakima River Basin Wetlands, Riparian, and Floodplain Habitat Plan .................... 3 1.2.2 Wetlands Enhancement Project ................................................................................. 3 2.0 PLAN OF STUDY.................................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................. 4 2.2 STUDY AREA .......................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 AUTHORITY -

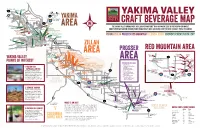

Yakima-Valley-Wineries-Map-Web.Pdf

TO CHINOOK PASS Oak Creek Bron Yr Aur Brewstillery 410 Brewing Co. Gard Ellensburg Vintners NACHES Canyon 12 Winery 821 TO WHITE PASS TIETON Yakima Rive S. Naches Road Southard Winery YAKIMA AND PACKWOOD TO ELLENSBURG Rowe Hill Dr Rowe Fontaine Estates AND SEATTLE NACHES 82 HEIGHTS 12 SELAH 823 AVA McGonagle Rd Goodlander Rd Rider Thompson Rd Nache Rive N Cellars AREA The Yakima Valley grows more hops, grapes and fruit than anywhere else in the Pacific Northwest. Cowiche Creek Valley The Bier Den Brewing Company Wherry Rd Brewing Co. AntoLin Cellars Come experience award-winning wine, unique craft beer and hand-crafted cider straight from the source. Naches Heights Weikel Rd Tieton Cider Works 5th Line Brewing Company Vineyard Visitor Information Center Fruitvale Blvd Wilridge Vineyard, 2 River Rd Winery & Distillery Hop Capital Single Hill Brewing Company Brewing Marble Rd The Distillarium YAKIMA ZILLAH PROSSER RED MOUNTAIN COLUMBIA GORGE BREWERY/CIDERY/DISTILLERY Bale Breaker Brewing Co. Swede Hill Distillery Wandering Hop Kana Winery YAKIMA Zier Rd Brewing Co. Yakima Air Terminal 24 Draper Rd MOXEE Gilbert 1 ZILLAH Cellars The KilnUNION GAP Winery Taproom Owen Roe 24 Wiley Rd Treveri Cellars RED MOUNTAIN AREA Knight Hill Winery PROSSER VanArnam Vineyards Freehand Cellars Hyatt Vineyards AREA Masset Two Mountain Winery Hightower Hamilton Ruby Magdalena Purple Star Cellars Winery Vineyards Dineen Vineyards Winery Cellars HopTown Tapteil Vineyard Wood Fired Pizza J.Bell Whitman Hill Winery 225 YAKIMA VALLEY Cellars NE Roza Road E. Corral Creek Road Silver Lake Winery/Vitis Spirits N. Whitmore PR NW E. 583 PR NE Col Solare Red Clark Rd Lombard Loop Sheridan Vineyard E. -

Yakima River Basin Yakima River Basin

40 YEARS LATER 2018 Water Security in the West Kristin Sleeper and Kaitlin Perkins UM BRIDGES Field Lab, Spring 2018 Yakima River Basin Yakima River Basin WATER SECURITY IN TH E W E S T Introduction The Yakima River Basin is a tributary of the broader Columbia River Basin, which spans through seven states and Canada before emptying into the Pacific Ocean. This region is the most productive agricultural area in Washington State and the largest producer of hops in the United States. Irrigation in the Yakima River Basin began in the mid-1800s when the land was taken from members of what is now the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Three Things You Should Know i. The Yakima Basin Integrated Water Resource Management Plan is the third phase of the Yakima River Basin Water Enhancement Project. The Plan is a watershed-scale approach to ensure sustainable water supplies for people, farms, and fish. ii. The Yakima River Basin stakeholders have competing demands, interests, and values, which set the stage for conflicts over water that are often controversial. These complex problems at the interface of people and nature require farmers, scientists, tribal members, federal agencies, the public, and decision makers to come together to build consensus, negotiate tradeoffs, and make decisions across a rapidly changing landscape. iii. The water rights adjudication process is ongoing in the Yakima River Basin, with the final results expected this spring. The court is substantiating nearly 2,300 water rights for individual properties in 31 tributary watersheds, and for 27 major claimants including irrigation districts, cities, federal projects, and the Yakama Indian Nation.