Federal Republic of Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kebbi State Draft 2021 Budget of Rejuvenation

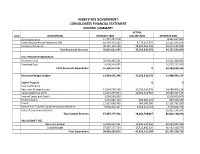

KEBBI STATE GOVERNMENT CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT GENERAL SUMMARY ACTUAL S/NO DESCRIPTION ESTIMATE 2020 JAN-SEP 2020 ESTIMATE 2021 Opening Balance 14,442,437,948 8,941,647,823 Internnaly Generated Revenue (IGR) 10,493,449,132 6,773,134,075 12,111,643,239 Statutory Allocation 30,125,125,519 28,483,202,503 43,674,243,838 Total Recurrent Revenue 55,061,012,599 35,256,336,578 64,727,534,900 Less: Recurrent Expenditure Personnel Cost 32,439,963,251 33,511,308,603 Overhead Cost 9,556,549,000 16,727,731,183 Total Recurrent Expenditure 41,996,512,251 0 50,239,039,786 Recurrent Budget Surplus 13,064,500,348 35,256,336,578 14,488,495,114 Capital Account 0 0 Opening Balance Recurrent Budget Surplus 13,064,500,348 35,256,336,578 14,488,495,114 Value Added Tax (VAT) 12,072,097,694 10,352,316,962 16,563,707,139 Internal Loans and Credit 5,000,000,000 8,900,000,000 External Loans 1,654,681,143 460,681,143 804,262,180 Grants 15,927,686,432 900,000,000 25,107,787,280 Other FAAC Transfers & Miscellaneous Revenue 9,968,212,147 2,395,413,354 3,572,812,754 Sales of Government Assets 16,025,134,503 Total Capital Revenue 57,687,177,764 49,364,748,037 85,462,198,970 2021 BUDGET SIZE Recurrent Budget 41,996,512,251 25,899,249,955 50,239,039,786 Capital Budget 57,687,177,764 15,523,880,329 85,462,198,970 Total Expenditure 99,683,690,015 41,423,130,284 135,701,238,756 KEBBI STATE GOVERNMENT 2021 REVENUE AND EXPENDITURES GENERAL SUMMARY REVIEWED ACTUAL REVENUE ESTIMATE 2020 JAN-SEP 2020 ESTIMATE 2021 INTERNALLY GENERATED REVENUE 10,493,449,132 6,773,134,075 -

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: the Igbo Experience

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: The Igbo Experience A thesis submitted to the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS), Universität Bayreuth, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Dr. Phil.) in English Linguistics By Uchenna Oyali Supervisor: PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe Mentor: Prof. Dr. Susanne Mühleisen Mentor: Prof. Dr. Eva Spies September 2018 i Dedication To Mma Ụsọ m Okwufie nwa eze… who made the journey easier and gave me the best gift ever and Dikeọgụ Egbe a na-agba anyanwụ who fought against every odd to stay with me and always gives me those smiles that make life more beautiful i Acknowledgements Otu onye adịghị azụ nwa. So say my Igbo people. One person does not raise a child. The same goes for this study. I owe its success to many beautiful hearts I met before and during the period of my studies. I was able to embark on and complete this project because of them. Whatever shortcomings in the study, though, remain mine. I appreciate my uncle and lecturer, Chief Pius Enebeli Opene, who put in my head the idea of joining the academia. Though he did not live to see me complete this program, I want him to know that his son completed the program successfully, and that his encouraging words still guide and motivate me as I strive for greater heights. Words fail me to adequately express my gratitude to my supervisor, PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe. His encouragements and confidence in me made me believe in myself again, for I was at the verge of giving up. -

Modelling Flooding Sites Around River Niger Area of Onitsha Town Nigeria Using Remote Sensing and GIS Application Dr Sylvanus Iro, Dr C.E Ezedike

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 11, Issue 2, February-2020 1027 ISSN 2229-5518 Title; Modelling Flooding sites around River Niger area of Onitsha town Nigeria using Remote Sensing and GIS Application Dr Sylvanus Iro, Dr C.E Ezedike Abstract; Increasing frequency and severity of flooding have caused tremendous damage in Onitsha area of Nigeria, requiring more efficient and effective way to reduce the risk and damage people face. In this study, the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of the study area was used in consideration of terrain's influence on flooding of the town. The Compound Topographic Index (CTI) of the area was calculated to extract areas that represent wetness, which shows areas liable to flooding. The DEM was further queried to identify the part of the town that will be flooded whenever River Niger rises to 5 metres above the current level. The result shows that of the 1226610m2 of the study area, flooding will inundate area approximately to 2400m2, representing 0.47% of the DEM cells of the total study area. The slope map indegrees identified areas with more than 890 to be safe from flood inundation when the river rises and areas less than 890 to be areas liable to flooding. The analysis of this model shows that the proposed model can be a valuable tool that will guide city planners to avoid areas that are liable to flooding being used as residential or commercial purposes and for minimising damages from flooding. Keywords: Flooding, River Niger, Remote Sensing, Geographic Information System and Digital Elevation Model. -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems Around the World

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Prepared for: State of Utah Great Salt Lake Advisory Council Prepared by: AECOM February 15, 2019 Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 13 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................. 13 III. APPROACH ............................................................................. 16 IV. CASE STUDIES OF DRYING LAKE SYSTEMS ...................... 17 1. LAKE URMIA ..................................................................................................... 17 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 18 b) Economic Consequences ............................................................................... 19 c) Social Consequences ..................................................................................... 20 d) Environmental Consequences ........................................................................ 21 e) Relevance to Great Salt Lake ......................................................................... 21 2. ARAL SEA ........................................................................................................ 22 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 22 b) Economic -

Batch 3 Group A

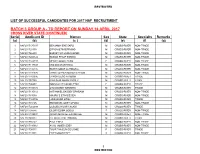

RESTRICTED LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR 2017 NAF RECRUITMENT BATCH 3 GROUP A - TO REPORT ON SUNDAY 16 APRIL 2017 CROSS RIVER STATE (CONTINUED) Serial Applicant ID Names Sex State Specialty Remarks (a) (b) (c ) (d) (e) (f) (g) 1 NAF2017175197 BENJAMIN ENE EKPO M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 2 NAF201728378 EFFIOM ETIM EFFIONG M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 3 NAF201746430 BASSEY SYLVANUS OKON M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 4 NAF2017200122 EDIKAN PHILIP ESSIEN M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 5 NAF2017148737 MERCY OKON EKPO F CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 6 NAF2017117347 ENE EDEM ANTIGHA M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 7 NAF2017186435 EDWIN IOBAR ACHIBONG M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 8 NAF2017191076 CHRISTOPHER MOSES EFFIOM M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 9 NAF2017166695 UKPONG ESO AKABOM M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 10 NAF201767788 PAULINUS OKON BASSEY M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 11 NAF201796402 IMMACULATA OKON ETIM F CROSS-RIVER TRADE 12 NAF2017100172 OTU BASSEY KENNETH M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 13 NAF2017135112 NATHANIEL BASSEY EPHRAIM M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 14 NAF201733038 MAURICE ETIM ESSIEN M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 15 NAF2017169796 LUKE OGAR OTAH M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 16 NAF201745165 EMMANUEL ODEY OFUNA M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 17 NAF2017202699 OGBUDU HILARY AGABI M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 18 NAF201798686 GLORY ELIMA ODIDO F CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 19 NAF2017199991 ADADA MICHAEL EKANNAZE M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 20 NAF201749812 CLEMENT ADIE BISONG M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 21 NAF201786142 PAUL ENEJI . M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 22 NAF2017180661 ACHU JAMES ODEY M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 23 NAF201706031 TOURITHA EUNICE USHIE F CROSS-RIVER -

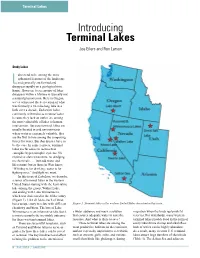

Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson

Terminal Lakes Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson Study Lakes akes tend to be among the more ephemeral features of the landscape Land generally are formed and disappear rapidly on a geological time frame. However, to see groups of lakes disappear within a lifetime is typically not a natural phenomenon. Here in Oregon, we’ve witnessed the desiccation of what was formerly a 16-mile-long lake in a little over a decade. Endorehic lakes, commonly referred to as terminal lakes because they lack an outlet, are among the most vulnerable of lakes to human intervention. Because terminal lakes are usually located in arid environments where water is extremely valuable, they are the first to lose among the competing forces for water. But that doesn’t have to be the case. In some respects, terminal lakes are far easier to restore than eutrophic/hypereutrophic systems. No expensive alum treatments, no dredging, no chemicals . just add water and life returns: but as those in West know, “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.” And fight we must. In this issue of LakeLine, we describe a series of terminal lakes in the western United States starting with the least saline lake among the group, Walker Lake, and ending with Lake Winnemucca, which was desiccated in the 20th century (Figure 1). Like all lakes, each of these has a unique story to relate with different Figure 1. Terminal lakes in the western United States described in this issue. chemistry and biota. The loss of Lake Winnemucca is an informative tale, but it a wider audience and reach a solution migration when the birds replenish fat is not necessarily the inevitable outcome that ensures adequate water to save the reserves. -

Nutrient Dynamics in the Jordan River and Great

NUTRIENT DYNAMICS IN THE JORDAN RIVER AND GREAT SALT LAKE WETLANDS by Shaikha Binte Abedin A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering The University of Utah August 2016 Copyright © Shaikha Binte Abedin 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Shaikha Binte Abedin has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Ramesh K. Goel , Chair 03/08/2016 Date Approved Michael E. Barber , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved Steven J. Burian , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved and by Michael E. Barber , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In an era of growing urbanization, anthropological changes like hydraulic modification and industrial pollutant discharge have caused a variety of ailments to urban rivers, which include organic matter and nutrient enrichment, loss of biodiversity, and chronically low dissolved oxygen concentrations. Utah’s Jordan River is no exception, with nitrogen contamination, persistently low oxygen concentration and high organic matter being among the major current issues. The purpose of this research was to look into the nitrogen and oxygen dynamics at selected sites along the Jordan River and wetlands associated with Great Salt Lake (GSL). To demonstrate these dynamics, sediment oxygen demand (SOD) and nutrient flux experiments were conducted twice through the summer, 2015. The SOD ranged from 2.4 to 2.9 g-DO m-2 day-1 in Jordan River sediments, whereas at wetland sites, the SOD was as high as 11.8 g-DO m-2 day-1. -

The Anambra- Imo River Basin and Rural Development Authority

University of Nigeria Research Publications ELECHI, Evaristus Emeghara Author Author PG/ Ph.D/98/26000 The Anambra- Imo River Basin and Rural Title Development Authority (Airbrda) 1976-2001 Arts Faculty Faculty History and International Studies Department Department May, 2006 Date Signature Signature THE ANAMBRA - IMO RIVER BASIN AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (AIRBRDA) 1976 - 2001 t EMEGHARA, EVARISTUS ELECHI PG / Ph. D /9&126,OOO. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES. UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. MAY, 2006. I I THE ANAMBRA - IMO RIVER BASIN AND RURAL DEVELOP EN7 AUTHORITY (AIRBRDA) 1976 - 2001 EMEGHARA, EVARISTUS ELECI-CI PG I Ph. D /!18/26,000m U.A.,M.A. (NIGERIA), MPA (IMSU), PGDE (CAIABAR) . A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph-D) IN ECONOMIC HISTORY t~ THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. ... 111 DECLARATION THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS DECLARES AS FOLLOWS: That Emeghara, Evaristus Elechi, a postgraduate student in the Department of History and International Studies, with Registration ; Number PGI Ph.D/98/26,000,l~assatisfactorily fulfilled the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economic titstory. The work embodied in this thesis is original and has not been submitted, in part or full, for any other diploma or degree of this or any other University. Supervisor .................................. ................................. Professor 0. N. Njoku Date Internal ~xaininer External Examin0."' r Date ........~,J.L~. t.h....... Mr. J. 0.~hazue$ Date Head of Department DECLARATION THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS DECLARES AS FOLLOWS: That Emeghara, Evaristus Elechi, a postgraduate student in the . Department of I-iistory and International Studies, with Registration ; Number PG/ Ph.D/98/26,OOO, has satisfactorily fulfilled the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economic History. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Nigeria Risk Assessment 2014 INSCT MIDDLE EAST and NORTH AFRICA INITIATIVE

INSCT MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA INITIATIVE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AND COUNTERTERRORISM Nigeria Risk Assessment 2014 INSCT MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA INITIATIVE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report—which uses open-source materials such as congressional reports, academic articles, news media accounts, and NGO papers—focuses on three important issues affecting Nigeria’s present and near- term stability: ! Security—key endogenous and exogenous challenges, including Boko Haram and electricity and food shortages. ! The Energy Sector—specifically who owns Nigeria’s mineral resources and how these resources are exploited. ! Defense—an overview of Nigeria’s impressive military capabilities, FIGURE 1: Administrative Map of Nigeria (Nations Online Project). rooted in its colonial past. As Africa’s most populous country, Nigeria is central to the continent’s development, which is why the current security and risk situation is of mounting concern. Nigeria faces many challenges in the 21st century as it tries to accommodate its rising, and very young, population. Its principal security concerns in 2014 and the immediate future are two-fold—threats from Islamist groups, specifically Boko Haram, and from criminal organizations that engage in oil smuggling in the Niger Delta (costing the Nigerian exchequer vast sums of potential oil revenue) and in drug smuggling and human trafficking in the North.1 The presence of these actors has an impact across Nigeria, with the bloody, violent, and frenzied terror campaign of Boko Haram, which is claiming thousands of lives annually, causing a refugee and internal displacement crises. Nigerians increasingly have to seek refuge to avoid Boko Haram and military campaigns against these insurgents. -

Inequalities in Access to Water and Sanitation in Rural Settlements in Parts of Southwest Nigeria

Inequalities in Access to Water and Sanitation in Rural Settlements in Parts of Southwest Nigeria Isaiah Sewanu Akoteyon Abstract Access to water, sanitation, and hygiene is a major human right necessary for achieving Sustainable Development Goals. The study examined inequalities in access to water and sanitation in rural settlements covering Apa, Ikoga, Ibeshe, Itori, Eruwa, and Lanlate in parts of Southwest Nigeria. Purposive and random sampling techniques were employed to select six settlements and administered 400 questionnaires to households respectively. Descriptive statistics, chi-square, and factor analysis were employed for data analysis. The result shows that the majority of the households interviewed are adults with secondary school certificate. The major available water supply and sanitation facilities in the study area are boreholes and an open pit latrine. About 50.8% and 48.1% of the households gained access to improved water and sanitation respectively in the study area. Badagry and Ewekoro recorded the highest access for improved water and sanitation respectively. Only 8% of the households gained access to safe water supply in the study area. The sanitary condition in the study area is poor. The chi-square shows a significant relationship between the dependent variables (water sources/types of toilet facilities) and independent variable (marital status, age, and income) at p<0.01. Factor analysis explained 68.86% of the total variance and extracted five components. The five factors revealed three major factors namely; demographic, environmental and water source as the main factors affecting household access to water and sanitation. The study is significant because it contributes to knowledge in the areas of WaSH and environmental sustainability.