468 Fchvs (234 in Each District) Trained on Detecting Mental Health Cases in the Community and Their Referral to Health Facilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal Electricity Authority

NEPAL ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIALMANAGEMENT PLAN OF SUPPLY AND INSTALLATION OF DISTRIBUTION PROJECTS (33KV TRANSMISSION LINE) UNDER THE GRID SOLAR AND ENERGY EFFICIECY PROJECT VOLUME II Prepared and Submitted by: Environment and Social Studies Department Kharipati, Bhaktapur Phone No.: 01-6611580, Fax: 01-6611590 Email: [email protected] September, 2018 SIDP Abbreviations and Acronyms ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS BS : Bikram Sambat (Nepali Era) DADO : District Agriculture Development Office DCC : District Coordination Committee DFO : District Forest Office DoED : Department of Electricity Development ESMF : Environment and Social Management Framework ESMP : Environment and Social Management Plan EPR : Environment Protection Rules, 1997 ESSD : Environment and Social Studies Department GoN : Government of Nepal GSEEP : Grid Tied and Solar Energy Efficiency Project GRC : Grievance Redress Cell GRM : Grievance Redress Mechanism HHs : Households IEE : Initial Environmental Examination MoEWRI : Ministry of Energy, Water Resource and Irrigation MoFE : Ministry of Forest and Environment NEA : Nepal Electricity Authority PAS : Project Affected Settlement PMO : Project Management Office SIDP : Supply and Installation of Distribution Project WB : World Bank Units ha : Hectare km : Kilometer kV : Kilo Volt m2 : Square meter ESMP Report i NEA-ESSD SIDP Table of Contents Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ........................................................................................ I 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

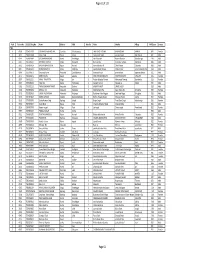

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

National Shelter Cluster Meeting

National Shelter Cluster Meeting Kathmandu 22 July 11am Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 1 Agenda 1. Welcome 2. Update from Government of Nepal (DUDBC) 3. Information Management 4. CCCM - DTM Round 3 5. Central Hub Update 6. Eastern Hub Update 7. Technical Update 8. Update on Recovery & Reconstruction Working Group 9. AOB Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 2 Update from Government of Nepal (DUDBC) Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 3 Information Management on Sheltercluster.org Brief introduction to the website Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 4 National Update Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 5 District Update . Emergency Shelter: . Self-Recovery: – Most Covered: Dolakha, – Most Covered: Rasuwa, Gorkha, Sindhulpalchok, Gorka, Rasuwa, Sinhupalchok Okhald. – Least Covered: All others <26% – Least covered: Ramechap, Makwanpur, Kavre, Bhaktapur, KTM Southeast Hub Northeast Hub West Hub Central Hub Total Damage (HH) according to GoN 13,138 28,225 39,916 73,647 52,000 66,636 62,461 32,054 58,262 87,726 25,508 62,143 27,990 9,450 639,156 Percentage (%) of total Damaged HHs in 14 2% 4% 6% 12% 8% 10% 10% 5% 9% 14% 4% 10% 4% 1% 100% Priority Districts Emergency: Tarpaulin + Tent Okhaldhunga Sindhuli Ramechhap Kabhrepalanchok Dolakha Sindhupalchok Dhading Makawanpur Gorkha Kathmandu Lalitpur Nuwakot Bhaktapur Rasuwa Grand Total Completed or Ongoing -

S.N. HO ID DISTRICT GP NP WARD NO SLIP No. GID

S.N. HO_ID DISTRICT GP_NP WARD_NO SLIP_No. GID GRIVIENT_NAME HOUSE OWNER FULL NAME REMARKS 1 2143890 Arghakhanchi Bhumikikasthan Urban Municipality 4 10007016 987015 Saraswati Sunar Saraswati Sunar Photo Repeated 2 2143901 Arghakhanchi Bhumikikasthan Urban Municipality 4 10007020 987019 Sarita Gharti Magar Sarita Gharti Magar Photo Repeated 3 2031434 Baglung Baglung Urban Municipality 12 9825974 306608 Sita Chhetri Sita Chhetri Photo Repeated 4 2031433 Baglung Baglung Urban Municipality 12 9825973 306609 Minu G.C.Chhetri Minu Gc Photo Repeated 5 2064892 Baglung Bareng Rural Municipality 1 9952049 987025 Simkali Sarkini No Photo 6 2165742 Baglung Wadigaun Rural Municipality 1 9824658 987001 Ambar Bahadur Pun Ambar Bahadur Pun No Photo 7 2165746 Baglung Wadigaun Rural Municipality 1 9824662 987005 Nem Bahadur Bhujel Nem Bahadur Bhujel No Photo 8 2165748 Baglung Wadigaun Rural Municipality 1 9824664 987007 Narayan Giri Narayan Giri No Photo 9 2165744 Baglung Wadigaun Rural Municipality 1 9824660 987003 Sante Kami Sante Kami No Photo 10 2165752 Baglung Wadigaun Rural Municipality 1 9824669 987011 Top Bahadur Thapa Top Bahadur Thapa No Photo 11 2165749 Baglung Wadigaun Rural Municipality 1 9824665 987008 Ganga Bahadur Thapa Ganga Bahadur Thapa No Photo 12 2165743 Baglung Wadigaun Rural Municipality 1 9824659 987002 Nar Bahadur Gharti Nar Bahadur Gharti No Photo 13 2165747 Baglung Wadigaun Rural Municipality 1 9824663 987006 Pobi Thapa Pobi Thapa No Photo 14 2165745 Baglung Wadigaun Rural Municipality 1 9824661 987004 Nare Kami Nare Kami No -

NEPAL: Ramechhap District

NEPAL: Ramechhap District - Manthali Municipality and Ramechhap Municipality HRHRRPRPHRRP 85°57'E 85°58'E 85°59'E 86°0'E 86°1'E 86°2'E 86°3'E 86°4'E 86°5'E 86°6'E 86°7'E 86°8'E 86°9'E 86°10'E 86°11'E 86°12'E Legend 27°27'N ¹½ School Chhap Kauseni Jiri Village Name Kalleri Kalleri Highway 27°26'N Kharpani 27°26'N District Road Patale Other Road Banre Ward no: 14 Kauchini Bharuwa Major Trail Ward no: 15 27°25'N Thakle Local Trail 27°25'N Ward no: 16 Kauchinibesi Municipal Boundary Pokhari Karambote Simpani Ward no: 4 Gogane Piple Ward Boundary Mugikholagaun Tekanpur " " " " " " Pokhari Dure Birta " "" Settlement Anpchaur Kabhre Tekanpur 27°24'N Rolini Kathjor Dunde Badi Muhan Ward no: 3 Mugikholagaun Tekanpur Kartike Piple Ward no: 5 Kuwapani Forest 27°24'N Akase Ward no: 13 Ramche Dandagaun Patale Odare Dahalgaun Bhatauli Kathjor Cultivation Thanti Thanti Dhand Gadwari Puranagaun Bhadaure Gairigaun Grassland Ward no: 2 Siddhidanda Manthali N.P. Archale Archale Pallo Gairathok Sani Madhau Ward no: 6 Thuli Madhau 27°23'N Mugitar Manthalighat Hariswanr Bush Nawalpur Khadwari 27°23'N Manthali Bhanjyang Thulitar Ralitar Gahate Ward no: 7 Dandagaun Kundahar Bhainsesur Sand / Gravel Kunauri Gairithok Sanpmare Thuli Madhu Hattitar Kunauri Kundhar Rahaltar Wallo Gairathok River / Stream Ward no: 1 Samalithan Kabilas Masantar Ritthabote Kalianp Dare Ward no: 10 Masantar 27°22'N Pond / Lake Dandakharka Pokhare Pandegaun Samalithan Deurali Manthali Thulachaur Salupati 27°22'N Dandakhoriya Ward no: 12 Bitar Kaijale Damaidanda Dandagaun Saunepani Keworepani -

Poverty Alleviation Fund

Poverty Alleviation Fund Poverty Alleviation Fund Earthquake Response Program Seven Days Mason Training List of Participants District: Ramechhap S.N Participant Name Address Citizen No Age Gender Contact No. Chhapabot, 1 Palten Tamang 48306 40 Male 9818911615 Rakathum 2 Chamar Dong Chapadi, Rakathum 213052/346 40 Male 9819679014 Dhan Bahadur 3 Chapadi, Rakathum 906 57 Male 9810169447 Tamang 4 Sonam Lama Labhu, Rakathum 40753 46 Male 9861591145 Khanigaun, 5 Chuntui Lama 211052-1222 34 Male 9818911615 Rakathum Dharapani, 6 Ramita Kumari Kadel 461 37 Female 9810216040 Rakathum Gam Bahadur Dharapani, 7 62366 63 Male 9823683500 Shrestha Rakathum 8 Raj Kumar Shrestha Ghatte, Bethan 65411 36 Male 9818722056 Purna Bahadur 9 Chapadi, Rakathum 911 33 Male - Pulami Man Bahadur 10 Chapadi, Rakathum 910 55 Male - Khadka 11 Binod Majhi Chihadi, Bethan 38100 42 Male 9818804256 12 Rajkrishna Shrestha Jugepani, Bethan 3859 47 Male 9802165681 Jakta Bahadur 211047/309 13 Amaldanda, Bethan 62 Male 9807634872 Shrestha 34 Dal Bahadur 14 Lada, Bethan 39066 31 Male 9813258659 Shrestha Dambar Bahadur 15 Ghatte, Bethan 2657 44 Male 9800877224 Tamang Harkha Bahadur 16 Garkot, Bethan 57934 55 Male 9803479249 Magar Karna Bahadur 17 Chapadi, Rakathum 213052/336 50 Male 9840201118 Magar Poverty Alleviation Fund Dhurba Bahadur 18 Lamatol, Bethan 1634/050 57 Male 9817829803 Khatri (Ghimire) Chhapabot, 19 Sanukaji Paudel 48306 49 Male 9818911615 Rakathum 20 Bikram Tamang Chapadi, Rakathum 213052/346 25 Male 9819679014 Ram Bahadur 21 Chapadi, Rakathum 906 43 Male 9810169447 -

Ramechhap VDC

Poverty Alleviation Fund Earthquake Response Program Seven Days Mason Training List of Participants District: Ramechhap VDC: Rakathum Training Duration: April 28, 2017-May 4, 2017 Venue: Lubu Partner Organization: Nepal MSR Centre SN Participant Name Address Citizen No Age Gender Contact No 1. Palten Tamang Chhapabot, Rakathum 48306 40 Male 9818911615 2. Chamar Dong Chapadi, Rakathum 213052/346 40 Male 9819679014 3. Dhan Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 906 57 Male 9810169447 Tamang 4. Sonam Lama Labhu, Rakathum 40753 46 Male 9861591145 5. Chuntui Lama Khanigaun, Rakathum 211052-1222 34 Male 9818911615 6. Ramita Kumari Dharapani, Rakathum 461 37 Female 9810216040 Kadel 7. Gam Bahadur Dharapani, Rakathum 62366 63 Male 9823683500 Shrestha 8. Raj Kumar Shrestha Ghatte, Bethan 65411 36 Male 9818722056 9. Purna Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 911 33 Male - Pulami 10. Man Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 910 55 Male - Khadka 11. Binod Majhi Chihadi, Bethan 38100 42 Male 9818804256 12. Rajkrishna Shrestha Jugepani, Bethan 3859 47 Male 9802165681 13. Jakta Bahadur Amaldanda, Bethan 211047/3093 62 Male 9807634872 Shrestha 4 14. Dal Bahadur Lada, Bethan 39066 31 Male 9813258659 Shrestha 15. Dambar Bahadur Ghatte, Bethan 2657 44 Male 9800877224 Tamang 16. Harkha Bahadur Garkot, Bethan 57934 55 Male 9803479249 Magar 17. Karna Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 213052/336 50 Male 9840201118 Magar 18. Dhurba Bahadur Lamatol, Bethan 1634/050 57 Male 9817829803 Khatri (Ghimire) 19. Sanukaji Paudel Chhapabot, Rakathum 48306 49 Male 9818911615 20. Bikram Tamang Chapadi, Rakathum 213052/346 25 Male 9819679014 21. Ram Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 906 43 Male 9810169447 Tamang 22. Man Bahadur Labhu, Rakathum 40753 54 Male 9861591145 Tamang 23. -

Dolakhatopographic Map - June 2015

fh N e p a l DolakhaTopographic Map - June 2015 3 000m. 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 000m. N N . 91 E 92 93 85°55'9E4 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 86°0E2 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 8160°5'E 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1868°10'E 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 2686°15'E 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 86°20'E35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 86°254'E3 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 86°5301'E 52 53 54 55 56 E. m m 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 1 1 1 1 3 3 17 17 17 17 N ' 0 1 ° N 8 5 ' 2 16 160 16 4 16 0 1 0 ° 8 2 15 15 15 15 5 2 0 T 14 0 14 14 50 14 a 00 m b 13 13 a 13 13 0 K 80 4 4 6 o 0 s 0 0 12 12 00 20 12 12 i 44 4 4 4 0 0 0 11 0 11 11 Lapchegaun 2 11 ! 4 0 000 0 31 5 31 4 i 10 4 10 10 4800 0 10 s 0 0 4 4 0 5 8 6 o 0 4 0 K 0 09 09 60 0 09 09 4 60 4 a 5000 b 08 5 m 08 6 08 08 0 0 0 a 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 0 4 5 T 0 5 0 5 N ' 0 4 5 5 0 07° 07 8 0 07 07 N 2 ' 5 0 ° Gumba 0 8 6 2 3800 5 06 06 06 06 0 0 8 5 4 6 Thasing ! 0 05 0 05 5 05 05 0 0 5 0 40 0 0 4 4 0 0 C H I N A 6 0 4 2 0 5 0 0 0 00 0 8 5 0 0 4 04 0 5 54 04 0 04 3 04 0 4800 u 0 0 4 h 6 0 600 5 0 C 4 0 4 0 2 0 4 0 5 0 00 r 03 0 5 0 6 03 0 03 0 0a3 0 0 6 6 5 5 h 0 0 Thangchhemu s 2 0 ! g 6 5 R o n 8 4 0 80 0 02 0 02 02 02 0 0 6 4 4 4 5 0 0 i 2 01 0 0 01 44 01 0 01 h 0 f s 5 ! 6 0 4 o 0 31 2 Lomnang 31 0 ! 00 0 K 00 00 5 00 4 0 e 0 0 f 0 600 ! 0 0 6 3 t 0 8 2 4 4 5 4 5 5 0 40 0 56 0 0 0 o 0 0 0 0 5 99 Tarkeghang 0 0 56 400 99 0 99 Lumnang 99 3 3 0 f 6 h 0 ! 2 3 0 0 4 ! 0 0 4 5 f 0 B 4 0 0 f 6 ! 4 Pangbuk 0 3 ! ! 0 0 6 0 0 5200 4 Pangbuk 98 0 98 N 0 98 98 ° 3 0 Goth 8 ! 2 N ° 5 3200 8 2 2 0 97 3 5 0 97 60 3 6 97 97 0 2 38 0 0 3 0 0 0 8 0 0 0 f 4 96 00 50 96 ! 0 Tatopani 18 96 0 -

Global Initiative on Out-Of-School Children

ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Government of Nepal Ministry of Education, Singh Darbar Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 4200381 www.moe.gov.np United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Institute for Statistics P.O. Box 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville Montreal Quebec H3C 3J7 Canada Telephone: +1 514 343 6880 Email: [email protected] www.uis.unesco.org United Nations Children´s Fund Nepal Country Office United Nations House Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk Lalitpur, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 5523200 www.unicef.org.np All rights reserved © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2016 Cover photo: © UNICEF Nepal/2016/ NShrestha Suggested citation: Ministry of Education, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Initiative on Out of School Children – Nepal Country Study, July 2016, UNICEF, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children © UNICEF Nepal/2016/NShrestha NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Tel.: Government of Nepal MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Singha Durbar Ref. No.: Kathmandu, Nepal Foreword Nepal has made significant progress in achieving good results in school enrolment by having more children in school over the past decade, in spite of the unstable situation in the country. However, there are still many challenges related to equity when the net enrolment data are disaggregated at the district and school level, which are crucial and cannot be generalized. As per Flash Monitoring Report 2014- 15, the net enrolment rate for girls is high in primary school at 93.6%, it is 59.5% in lower secondary school, 42.5% in secondary school and only 8.1% in higher secondary school, which show that fewer girls complete the full cycle of education. -

Section 3 Zoning

Section 3 Zoning Section 3: Zoning Table of Contents 1. OBJECTIVE .................................................................................................................................... 1 2. TRIALS AND ERRORS OF ZONING EXERCISE CONDUCTED UNDER SRCAMP ............. 1 3. FIRST ZONING EXERCISE .......................................................................................................... 1 4. THIRD ZONING EXERCISE ........................................................................................................ 9 4.1 Methods Applied for the Third Zoning .................................................................................. 11 4.2 Zoning of Agriculture Lands .................................................................................................. 12 4.3 Zoning for the Identification of Potential Production Pockets ............................................... 23 5. COMMERCIALIZATION POTENTIALS ALONG THE DIFFERENT ROUTES WITHIN THE STUDY AREA ...................................................................................................................................... 35 i The Project for the Master Plan Study on High Value Agriculture Extension and Promotion in Sindhuli Road Corridor in Nepal Data Book 1. Objective Agro-ecological condition of the study area is quite diverse and productive use of agricultural lands requires adoption of strategies compatible with their intricate topography and slope. Selection of high value commodities for promotion of agricultural commercialization -

Cg";"Lr–1 S.N. Application ID User ID Roll No बिज्ञापन नं. तह पद उम्मेदव

cg";"lr–1 S.N. Application ID User ID Roll No बिज्ञापन नं. तह पद उ륍मेदवारको नाम लऱगं जꅍम लमतत सम्륍मलऱत हुन चाहेको समूह थायी न. पा. / गा.वव.स-थायी वडा नं, थायी म्ज쥍ऱा नागररकता नं. 1 85994 478714 24001 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager ANIL NIROULA Male 2040/01/09 खलु ा Biratnagar-5, Morang 43588 2 86579 686245 24002 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager ARJUN SHRESTHA Male 2037/08/01 खलु ा Bhadrapur-13, Jhapa 1180852 3 28467 441223 24003 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager ARUN DHUNGANA Male 2041/12/17 खलु ा Myanglung-2, Tehrathum 35754 4 34508 558226 24004 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager BALDEV THAPA Male 2036/03/24 खलु ा Sikre-7, Nuwakot 51203 5 69018 913342 24005 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager BHAKTA BAHADUR KHATRI CHATRI Male 2038/12/25 खलु ा PUTALI BAZAR-14, Syangja 49247 6 89502 290954 24006 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager BIKAS GIRI Male 2034/03/15 खलु ा Kathmandu-31, Kathmandu 586/4042 7 6664 100010 24007 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager DINESH GAUTAM Male 2036/03/11 खलु ा Nepalgunj-12, Banke 839 8 62381 808488 24008 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager DINESH OJHA Male 2036/12/15 खलु ा Biratnagar Metropolitan-12, Morang 1175483 9 89472 462485 24009 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager GAGAN SINGH GHIMIRE Male 2033/04/26 खलु ा MAIDAN-3, Arghakhanchi 11944/3559 10 89538 799203 24010 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager GANESH KHATRI Male 2028/07/25 खलु ा TOKHA-5, Kathmandu 4/2161 11 32901 614933 24011 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager KHIL RAJ BHATTARAI Male 2039/08/08 खलु ा Bhaktipur-6, Sarlahi 83242429 12 70620 325027 24012 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager KRISHNA ADHIKARI Male 2038/03/23 खलु ा walling-10,