Download This Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

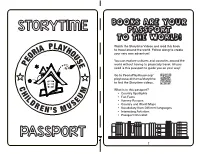

STORYTIME PASSPORT to the WORLD! L Watch the Storytime Videos and Read This Book a P AYH to Travel Around the World

BOOKS ARE YOUR STORYTIME PASSPORT TO THE WORLD! L Watch the Storytime Videos and read this book A P AYH to travel around the world. Follow along to create RI O your very own adventure! O U E S You can explore cultures and countries around the P E world without having to physically travel. All you need is this passport to guide you on your way! Go to PeoriaPlayHouse.org/ playhouse-at-home/storytime to find the Storytime videos. C What is in this passport? H M • Country Spotlights IL U • Fun Facts D E • Yummy Recipes R S • Country and World Maps E U • Vocabulary from Different languages N’S M • Interesting Activities • Passport Checklist PASSPORT 2 Create Your Own Passport! A passport allows you to go from one country to another. Make your own passport here to explore the world with the PlayHouse! Listen to the story Finders Keepers? NAME: A True Story in India written by Robert Arnett and illustrated by Add Your Smita Turakhia Picture Here https://youtu.be/ -_58v9qB_04 DATE OF BIRTH: Finders Keepers? A True Story in India is a story about doing the right thing. Think about the different ways you can do the right thing or help NATIONALITY: people through good deeds. What are a few you (country you live in) can think of? SIGNATURE: A PLAYH RI O O U E S P E India is very diverse, which means people come ID NUMBER: from a lot of different backgrounds. India is a (make your own big country, and there are many differences in 9 digit number ) C the way people live including what they eat, the H M I U language they speak, and the type of clothing L E D R S they wear. -

Rhyming Dictionary

Merriam-Webster's Rhyming Dictionary Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Springfield, Massachusetts A GENUINE MERRIAM-WEBSTER The name Webster alone is no guarantee of excellence. It is used by a number of publishers and may serve mainly to mislead an unwary buyer. Merriam-Webster™ is the name you should look for when you consider the purchase of dictionaries or other fine reference books. It carries the reputation of a company that has been publishing since 1831 and is your assurance of quality and authority. Copyright © 2002 by Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merriam-Webster's rhyming dictionary, p. cm. ISBN 0-87779-632-7 1. English language-Rhyme-Dictionaries. I. Title: Rhyming dictionary. II. Merriam-Webster, Inc. PE1519 .M47 2002 423'.l-dc21 2001052192 All rights reserved. No part of this book covered by the copyrights hereon may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission of the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America 234RRD/H05040302 Explanatory Notes MERRIAM-WEBSTER's RHYMING DICTIONARY is a listing of words grouped according to the way they rhyme. The words are drawn from Merriam- Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. Though many uncommon words can be found here, many highly technical or obscure words have been omitted, as have words whose only meanings are vulgar or offensive. Rhyming sound Words in this book are gathered into entries on the basis of their rhyming sound. The rhyming sound is the last part of the word, from the vowel sound in the last stressed syllable to the end of the word. -

Table of Contents

1 Table of Contents 2 Letter Words .................................................................................................................................2 3 Letter Words .................................................................................................................................3 4 Letter Words .................................................................................................................................5 5 Letter Words ...............................................................................................................................12 6 Letter Words ...............................................................................................................................25 7 Letter Words ...............................................................................................................................43 8 Letter Words ...............................................................................................................................60 All words are taken from OWL 22 HOW TO USE THIS DOCUMENT Have you ever wanted to maximize your studying time? Just buzzing through word lists do not ensure that you will ever play the word….ever. The word lists in this document were run through 917,607 full game simulations. Only words that were played at least 100 times are in this list and in the order of most frequently played. These lists are in order or probability to play with the first word being the most probable. To maximize the use of this list is easy. Simply -

The History of the Sno Cone

The History of the Sno Cone Ah the sno cone, most of us has had one as a kid and some of us enjoy them as adults. So just how long have sno cones been around you might ask? And who invented them? To start, the spelling of snow cone varies according to how it is prepared or sometimes just out of tradition. Most retail shaved ice outlets in New Orleans for instance, spell the name of their product sno-cone without the w. This spelling identifies the product to all New Orleanians and indicates an ethnic heritage to the long- standing tradition. For many others it is simply spelled snow cone. Tracing back the sno cone's origin, it is believed that it was invented during the milwaukee roofing contractors Roman Empire (27 B.C. to A.D. 395). Snow was hauled from the mountaintops to the city, syrup was added and people had flavored snow. By the late 1800s and early 1900s, when it came to shaving ice or 'snow', a wood commercial roofing supply plane was used. Hand held ice shavers were designed solely to produce sno-balls. Numerous manufacturers were creating such shavers by the late eighteen hundreds. In 1920, Samuel Bert of Dallas, Texas invented a snow cone making machine. A year earlier, he sold shaved ice at the 1919 State Fair of Texas. Ernest Hansen, an inventor from New Orleans, patented the first motorized ice block shaver in 1934. Hansen was helped by his wife who created several flavors of syrup to be added to the shaved ice, which came to be known as "snowballs". -

Early Versus Extended Exposure in Speech and Vocabulary Learning: Evidence from Switched-Dominance Bilinguals

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Early versus Extended Exposure in Speech and Vocabulary Learning: Evidence from Switched-dominance Bilinguals A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Linguistics By Michael Blasingame EVANSTON, ILLINOIS March 2018 2 © Copyright by Michael Blasingame All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT Both the timing (i.e., ‘when’) and amount (i.e., ‘how much’) of language exposure have been shown to affect language-learning outcomes. Monolinguals and (most) bilinguals confound these two factors of early exposure and extended exposure (i.e., their first-acquired language is their most used or dominant language), making it difficult to isolate the benefits that either one of these exposure patterns could provide independently for language acquisition. Switched- dominance bilinguals (i.e., heritage speakers) dissociate early and extended exposure as their first-acquired language (L1) is considerably weaker (non-dominant) compared to their stronger (dominant) second-acquired language (L2). This dissociation allows us to examine the unique benefits of both early and extended exposure on language acquisition. The current study focuses on how these exposure patterns affect speech and vocabulary learning in heritage speakers (L2- dominant) in three separate experimental paradigms. In Experiment 1, Spanish heritage speakers (SHS) recorded sentences in Spanish (their non-dominant L1) and English (their dominant L2) along with L1-dominant Spanish and English controls in their respective (dominant) L1s. These sentences, embedded in noise at two signal-to- noise ratios (-4 dB and -8 dB signal-to-noise ratio; SNR), were presented aurally to L1-dominant listeners of Spanish and English, respectively. -

01 001 01 01 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC.LA ESPERAZA No 2 Carrera 29 No

01 001 01 01 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC.LA ESPERAZA No 2 Carrera 29 No. 102A-20 01 001 01 02 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN INST.EDUC. LA CANDELARIA Calle 106 No. 32-100 01 001 01 03 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN INST.EDUC.MARIA DE LOS A. Calle 103 No. 33D-75 01 001 02 01 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC. PABLO VI Carrera 42B No. 110 A 28 01 001 02 02 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC. AGRIPINA MONTES DEL Calle 95 No. 42B-44 01 001 02 03 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC. MEDELLIN Calle 96 No. 36-45 01 001 02 04 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC. DIVINA PROVIDENCIA Calle 108 No 43B - 17 01 001 03 01 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN INST. EDUC. ASIA IGNACIANA Calle 122 N° 51B-30 01 001 03 02 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC. MANUEL URIBE ANGEL Carrera 49A No.107-65 01 001 03 03 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN INST.EDUC. BARRIO SANTA CRUZ Calle 101 No. 43A-23 01 001 03 04 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC. REPUB. DE NICARAGUA Carrera 48 No. 103B-01 01 001 03 05 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC. ARZOBISPO GARCIA Carrera 49 No. 98-48 01 001 03 06 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN INST.EDUC. REPUB. DE HONDURAS Carrera 50B No. 97A-30 01 001 04 01 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN INST.EDUC. REPUBLICA BARBADOS Carrera 36 No. 85B-140 01 001 04 02 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN INST.EDUC. SAN LORENZO DE A. Carrera 39 No. 80-33 01 001 04 03 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN INSTITUTO VICARIAL JESUS M. Carrera 45 No. 85-154 01 001 05 01 ANTIOQUIA MEDELLIN SEC.ESC.NTRA SRA DE LAS NIEVE Calle 79 No. -

La Prensa.Único Diario Español E Hispano Americano En Nueva York

OFICINAS: t46 CANAL ST. —NEW YORK ijjfinpo prob«K)«; TELEFONO: CANAL fl-1200 .„sjn<lo y teiinilncio. r' EL UN.CO D.AR,0 ESPAÑOL E HISPANO AMER.CANO DE NUEVA YORK CON CIRCULACION CERTIFICADA POR EL A. B. C. TRES CENTAVOS NUEVA YORK, LUNES 17 DE JULIO DE 1933 «a mu, NUMERO 5189 '•"So, Ka I <\>T| ifj Los secuestros aumentan; ""V ci, KM. aarantías de Machado alPor su interés en Barbarán y Collar V. • i:. N. oposición, conocidas hoy Madrid rindió ayer homenaje a Méjico Ortiz Rubio es amenazado NEW Se confirma aue el desastre del "Cuatro Vientos" acae- [ LA FAMILIA DEL JOVEN EL EX-PDTE. MEJICANO WELLES PRESENTARÁ CUSTODIADO POR LA hii.ir.i . ció en el Golfo.—La cámara de neumático hallada en O'CONNELL ESPERA EL RESPUESTA OFICIAL AL JUL Tabasco perteneció al avión español.—Se va a renovar, AVISO DE LA PANDILLA POLICIA DE SAN DIEGO min;,| rf sevel t listo a imponer un alza en PLAN DE LA OPOSICIÓN -I su bihoueda "tM.Irrj Se le ha exigido $50,000 KH. Las últiman noticias que llegan La madre del joven secues- I sueldos a todas las industrias la censura periodística ce- MADRID, julio H> (/Pl—Hoy so para librarse de "una - riin^.s efectuó 'en esta ciudad el primer aquí de Méjico parecen confirmar trado de Albany acudió f¡ • de manera definitiva que los avia- Ini1)t*r só ayer y sólo queda un honier.aje que se celebra en mu- suerte peor fiñO de obreros comienzan hoy a ganar máfí.— nac¡Br4 cho.< años a una nación extranje- dores se perdieron en el Golfo cié ayer a misa <1. -

Indigenismos Léxicos En Las Publicaciones Periodísticas De Santiago De Chile

BFUCh XXX ( 1979): 105-240 Indigenismos léxicos en las publicaciones periodísticas de Santiago de Chile Luis Prieto El presente artículo da cuenta de los resultados de un estudio que tiene por propósito determinar, cuantitativa y cualitativamente, la contribución léxica de las lenguas amerindias al español escrito ele Chile, en ttna de sus ma nifestaciones más caracterizadas: sus publicaciones perio dísticas. El autor realiza su análisis en un corpus compuesto por 68 publicaciones periodísticas (34 diarios y 24 revistas), editaclas en la ciudad capital del país, durante los meses de fttlio y agosto de 1976. Los indigenismos léxicos son estudiados desde los si guientes puntos de vista: etimología, fonética, morfología. lexicogenesia, vitalidad, frecuencia ele uso y densidad. Se ofrece, asimismo, un glosario etimológico ejemplificado de los indoamericanísmos recopilados. Entre los resultados más importantes de esta investiga- • ción, pueden destacarse: la escasa densidad del elemento indígena en la masa léxica total del corpus ( estimada en 2.278.000 palabras), que alcanza al 0,04 de la misma; la preponclerancia de los indoamericanismos provenien tes de dos lenguas regionales ( quechua y mapuche), con alrededor del 75% del. total; la preeminencia de los que chuismos sobre las voces de la 71ri11eipal lengtta aborigen del país, el mapuche ( con un 42 y un 34% del total, respec tivamente); la concentración de los indigenismos en torno a cuatro macrod,0minios semánticos: la flora, la alimenta ción, la fauna y el folklore; la prácticamente total adap- 106 LUIS PRIETO tación de las voces indígenas a las norma.s fonéticas y mor fol6gicas del castellano, como asimismo su casi total aco modación al sistema grafemático castellano. -

Fruit Smoothie Batido De Frutas

FRUIT SMOOTHIE BATIDO DE FRUTAS Ingredients: M 1 (6 ounce) can frozen orange juice or lemonade concentrate M 1 1/2 cups milk M 1/4 cup sugar (optional) M 1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract M 10 cubes ice Directions: In a blender, combine juice concentrate, milk, sugar (optional), vanilla, and ice cubes. Blend until smooth. Pour into glasses and serve. Yum! While you make your cool treat, review the Spanish words for the ingredients you are using: ● the ice – el hielo ● the milk – la leche ● the orange – la naranja ● the lemonade – la limonada PLEASE NOTE: While fruits and vegetables are an important part of the foods we eat, “sweet treats” are delights to have on occasion. Only at pbskids.org/noah Oh Noah! is a production of THIRTEEN for WNET. © 2012 THIRTEEN. All rights reserved. Oh Noah! is a trademark of THIRTEEN. The PBS KIDS GO! logo is a registered mark of PBS and is used with permission. FRUITY SNOW CONES RASPADO Ingredients (for 2-3 servings): M 1 (6 ounce) can frozen orange juice or lemonade concentrate M 20-30 ice cubes M 3 plastic cups Directions: 1. In a blender crush ice cubes using the pulse setting. Pour crushed ice into plastic cups. 2. Pour desired flavor concentrate over the ice and enjoy. While you make your cool treat, review the Spanish words for the ingredients you are using: ● the ice – el hielo ● the orange – la naranja ● the lemonade – la limonada Snack time discussion In the United States we call this treat a “snow cone,” but this treat has various names throughout Latin America. -

Walking Tour of Old San Juan, Puerto Rico

Walking Tour of Old San Juan, Puerto Rico Compiled by: Michael Scott, Salisbury University, Salisbury, Maryland ([email protected]) Stop Order and Inspiration: Accurate Communications & Orlando Mergal (www.accuratecommunications.com) Text for locations: Puerto Rico Tourism Company (eyetour.com – also shows videos of each of these sites) Orthophotography: UPR‐Graduate School of Planning, PR Planning Board, VITO Belgium, FugroEarth Data Inc. (gis.otg.gobierno.pr) 1. Plaza de la Dársena & La Casita To the west of the Marina and overlooking the San Juan Bay you’ll find one of the many enjoyable plazas that San Juan has to offer. Plaza de la Dársena is best known for its permanent crafts market usually held on weekends. The ‘small house’ or La Casita in this plaza was originally built for the Department of Agriculture and Commerce and dates back to 1937. It now functions as an information center run by the Puerto Rico Tourism Company. The plaza is also home to a statue of Henry the Navigator, Prince of Portugal. 2. Plaza de Hostos Directly in front of Plaza de la Dársena and La Casita, is La Plaza de Hostos, named after “The Citizen of the Americas” Eugenio María de Hostos. An avid supporter of the independence movement for Puerto Rico and Cuba, Hostos dedicated his life to educational causes, helping Peru and the Dominican Republic in organizing their educational systems as well as advocating women’s rights to higher education. A bust of Hostos adorns this plaza, where you can find numerous food vendors with typical fried treats and sweets, artisans, and locals playing dominos and enjoying the shade. -

The Odd Couple ODD LETTER PAIRS / PLACEMENT in Imported (Only) Words

The Odd Couple ODD LETTER PAIRS / PLACEMENT in imported (only) words. Become familiar with these odd transliterations. compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club Ends with -AA MARKKAA AAAKKMR MARKKA, former monetary unit of Finland [n] RUFIYAA AAFIRUY monetary unit of Maldives [RUFIYAA] Ends with -AC CHAMPAC AACCHMP champak (East Indian tree) [n -S] MUNTJAC ACJMNTU small Asian deer [n -S] YASHMAC AACHMSY yashmak (veil worn by Muslim women) [n -S] Ends with -AH AGGADAH AAADGGH haggadah (biblical narrative) [n -S, -DOT, -DOTH] BEGORAH ABEGHOR begorra (used as mild oath) [interj] CHALLAH AACHHLL kind of bread [n -S, -LLOT, -LLOTH] CHEETAH ACEEHHT swift-running wildcat [n -S] CHUDDAH ACDDHHU chuddar (large, square shawl) [n -S] CHUPPAH ACHHPPU canopy used at Jewish wedding [n -S, -PPOT] DJIBBAH ABBDHIJ jibba (long coat worn by Muslim men) [n -S] GOOMBAH ABGHMOO older man who is friend [n -S] HALAKAH AAAHHKL halacha (legal part of Talmud) [n -S, -KOTH] HALALAH AAAHHLL halala (Saudi Arabian coin) [n -S] HALAVAH AAAHHLV halvah (Turkish confection) [n -S] HUTZPAH AHHPTUZ chutzpah (supreme self-confidence) [n -S] KHIRKAH AHHIKKR patchwork garment [n -S] MENORAH AEHMNOR candleholder used in Jewish worship [n -S] MEZUZAH AEHMUZZ Judaic scroll [n -S, -ZOT, -ZOTH] MITSVAH AHIMSTV mitzvah (commandment of Jewish law) [n -S, -VOTH] MITZVAH AHIMTVZ commandment of Jewish law [n -S, -VOTH] PADSHAH AADHHPS padishah (sovereign) [n -S] QABALAH AAABHLQ cabala (occult or secret doctrine) [n -S] SHARIAH AAHHIRS sharia (Islamic law based on Koran) [n -S] -

In the Heights” Music and Lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda July 12-Aug

Next on our stage: GOD OF CARNAGE MAKING GOD LAUGH MOTHERS AND SONS SEPT. 13-OCT. 14 NOV. 15-DEC. 23 JAN. 17-FEB. 17 HIGHLIGHTS A companion guide to “In the Heights” music and lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda July 12-Aug. 19, book by Quiara Alegría Hudes conceived by Lin-Manuel Miranda 2018 directed by Jeffrey Bracco Synopsis In the Heights tells the universal story of a vibrant community in New York’s Washington Heights neighborhood — a place where the coffee from the corner bodega is light and sweet, the windows are always open and the breeze carries the rhythm of three generations of music. It’s a community on the brink of change, full of hopes, dreams and pressures, where the biggest struggles can be deciding which traditions you take with you, and which ones you leave behind. Characters Along with a lively ensemble, In the Heights features several unforgettable principal and featured characters. Usnavi (Oklys Pimentel): From his corner bodega, our charmingly awkward narrator sees all the neighborhood’s stories, even as he yearns to write a new one for himself by returning to his family’s home in the Dominican Republic. Vanessa (Alycia Adame): Sassy and determined, Vanessa has big plans to make it out of the barrio and build a new life downtown. Nina (Cristina Hernandez): Nina may be “the one who made it out,” but balancing her studies and workload at Stanford Above: Usnavi (Oklys Pimentel, left) owns the corner barrio where he University hasn’t been a dream. misses nothing in the neighborhood.