South Bank Arts Centre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Bank Conservation Area Statement 2007 Conservation Area

South BankSouth Bank Conservation Area Statement 2007 Conservation Area Conservation Area Statement September 2007 South Bank Conservation Area Statement 2007 Conservation Area Context Map This map shows the South Bank Conservation Area (CA 38) in its wider context which includes the following neighbouring conservation areas: - CA 09 Walcot Conservation Area (part only) CA 10 Lambeth Palace Conservation Area CA 21 Roupell Street Conservation Area CA 34 Waterloo Conservation Area CA 40 Lower Marsh Conservation Area CA 50 Lambeth Walk & China Walk Conservation Area CA 51 Mitre Road & Ufford Street Conservation Area 2 South Bank Conservation Area Statement 2007 Conservation Area Boundary Map The maps in this document are based upon Ordnance Survey material with permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised preproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prose- cution or civic proceedings. LB Lambeth 100019338 2007. 3 South Bank Conservation Area Statement 2007 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 5 1. PLANNING FRAMEWORK 6 2. CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 7 2.1 Purpose and structure of a Conservation Area Appraisal 7 2.2 Historic Development 7 2.3 City Context & Strategic Views 11 2.4 Archaeology 11 2.5 Spatial Form 11 2.6 Streetscape 14 2.7 Permeability 16 2.8 Public Realm 17 2.9 Access 17 2.10 Street Furniture 18 2.11 Public Art 19 2.12 Activity and Uses 19 2.13 Spaces 20 2.14 Built form 21 2.15 Listed Buildings 22 2.16 Locally Listed Buildings 23 2.17 Buildings making a Positive Contribution 23 2.18 Buildings Making a Neutral Contribution 26 2.19 Buildings Making a Negative Contribution 26 2.20 Spaces Making a Positive Contribution 27 2.21 Spaces Making a Neutral Contribution 28 2.22 Spaces Making A Negative Contribution 29 2.23 Important Local Trees 29 2.24 Important Local Views 29 2.25 Signs & Advertisements 30 2.26 Setting of the Conservation Area 31 2.27 Appraisal Conclusion 31 4 South Bank Conservation Area Statement 2007 PAGE 3. -

Planning Weekly List & Decisions

Planning Weekly List & Decisions Appeals (Received/Determined) and Planning Applications & Notifications (Validated/Determined) Week Ending 09/10/2020 The attached list contains Planning and related applications being considered by the Council, acting as the Local Planning Authority. Details have been entered on the Statutory Register of Applications. Online application details and associated documents can be viewed via Public Access from the Lambeth Planning Internet site, https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/planning-and-building- control/planning-applications/search-planning-applications. A facility is also provided to comment on applications pending consideration. We recommend that you submit comments online. You will be automatically provided with a receipt for your correspondence, be able to track and monitor the progress of each application and, check the 21 day consultation deadline. Under the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985, any comments made are open to inspection by the public and in the event of an Appeal will be referred to the Planning Inspectorate. Confidential comments cannot be taken into account in determining an application. Application Descriptions The letters at the end of each reference indicate the type of application being considered. ADV = Advertisement Application P3J = Prior Approval Retail/Betting/Payday Loan to C3 CON = Conservation Area Consent P3N = Prior Approval Specified Sui Generis uses to C3 CLLB = Certificate of Lawfulness Listed Building P3O = Prior Approval Office to Residential DET = Approval -

17 River Prospect: Golden Jubilee/ Hungerford Footbridges

17 River Prospect: Golden Jubilee/ 149 Hungerford Footbridges 285 The Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges flank the Hungerford railway bridge, built in 1863. The footbridges were designed by the architects Lifschutz Davidson and were opened as a Millennium Project in 2003. 286 There are two Viewing Locations at Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges, 17A and 17B, referring to the upstream and downstream sides of the bridge. 150 London View Management Framework Viewing Location 17A Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges: upstream N.B for key to symbols refer to image 1 Panorama from Assessment Point 17A.1 Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges: upstream - close to the Lambeth bank Panorama from Assessment Point 17A.2 Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges: upstream - close to the Westminster bank 17 River Prospect: Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges 151 Description of the View 287 Two Assessment Points are located on the upstream side of Landmarks include: the bridge (17A.1 and 17A.2) representing the wide swathe Palace of Westminster (I) † of views available. A Protected Silhouette of the Palace of Towers of Westminster Abbey (I) Westminster is applied between Assessment Points 17A.1 The London Eye and 17A.2. Westminster Bridge (II*) Whitehall Court (II*) 288 The river dominates the foreground. In the middle ground the London Eye and Embankment trees form distinctive Also in the views: elements. The visible buildings on Victoria Embankment The Shell Centre comprise a broad curve of large, formal elements of County Hall (II*) consistent height and scale, mostly of Portland stone. St Thomas’s Hospital (Victorian They form a strong and harmonious building line. section) (II) St George’s Wharf, Vauxhall 289 The Palace of Westminster, part of the World Heritage Site, Millbank Tower (II) terminates the view, along with the listed Millbank Tower. -

SOUTH BANK GUIDE One Blackfriars

SOUTH BANK GUIDE One Blackfriars The South Bank has seen a revolution over the past 04/ THE HEART OF decade, culturally, artistically and architecturally. THE SOUTH BANK Pop up restaurants, food markets, festivals, art 08/ installations and music events have transformed UNIQUE the area, and its reputation as one of London’s LIFESTYLE most popular destinations is now unshakeable. 22/ CULTURAL Some of the capital’s most desirable restaurants and LANDSCAPE bars are found here, such as Hixter, Sea Containers 34/ and the diverse offering of The Shard. Culture has FRESH always had a place here, ever since the establishment PERSPECTIVES of the Festival Hall in 1951. Since then, it has been 44/ NEW joined by global champions of arts and theatre such HORIZONS as the Tate Modern, the National Theatre and the BFI. Arts and culture continues to flourish, and global businesses flock to establish themselves amongst such inspiring neighbours. Influential Blue Chips, global professional and financial services giants and major international media brands have chosen to call this unique business hub home. With world-class cultural and lifestyle opportunities available, the South Bank is also seeing the dawn of some stunning new residential developments. These ground-breaking schemes such as One Blackfriars bring an entirely new level of living to one of the world’s most desirable locations. COMPUTER ENHANCED IMAGE OF ONE BLACKFRIARS IS INDICATIVE ONLY 1 THE HEART OF THE SOUTH BANK THE SHARD CANARY WHARF 30 ST MARY AXE STREET ONE BLACKFRIARS TOWER BRIDGE -

From Manufacturing Industries to a Services Economy: the Emergence of a 'New Manchester' in the Nineteen Sixties

Introductory essay, Making Post-war Manchester: Visions of an Unmade City, May 2016 From Manufacturing Industries to a Services Economy: The Emergence of a ‘New Manchester’ in the Nineteen Sixties Martin Dodge, Department of Geography, University of Manchester Richard Brook, Manchester School of Architecture ‘Manchester is primarily an industrial city; it relies for its prosperity - more perhaps than any other town in the country - on full employment in local industries manufacturing for national and international markets.’ (Rowland Nicholas, 1945, City of Manchester Plan, p.97) ‘Between 1966 and 1972, one in three manual jobs in manufacturing were lost and one quarter of all factories and workshops closed. … Losses in manufacturing employment, however, were accompanied (although not replaced in the same numbers) by a growth in service occupations.’ (Alan Kidd, 2006, Manchester: A History, p.192) Economic Decline, Social Change, Demographic Shifts During the post-war decades Manchester went through the socially painful process of economic restructuring, switching from a labour market based primarily on manufacturing and engineering to one in which services sector employment dominated. While parts of Manchester’s economy were thriving from the late 1950s, having recovered from the deep austerity period after the War, with shipping trade into the docks at Salford buoyant and Trafford Park still a hive of activity, the ineluctable contraction of the cotton industry was a serious threat to the Manchester and regional textile economy. Despite efforts to stem the tide, the textile mills in 1 Manchester and especially in the surrounding satellite towns were closing with knock on effects on associated warehousing and distribution functions. -

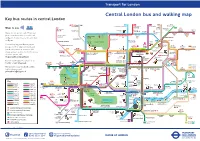

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Shell International Finance B.V. Royal Dutch Shell Plc

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM SHELL INTERNATIONAL FINANCE B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in The Netherlands and having its statutory domicile in The Hague) as Issuer ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC (incorporated with limited liability in England) as Issuer and Guarantor U.S.$25,000,000,000 DEBT SECURITIES PROGRAMME _________________________________________________________________________________________ Arranger UBS INVESTMENT BANK Dealers BARCLAYS BNP PARIBAS BOFA MERRILL LYNCH CITIGROUP CREDIT SUISSE DEUTSCHE BANK GOLDMAN SACHS INTERNATIONAL HSBC J.P. MORGAN LLOYDS BANK MORGAN STANLEY RBC CAPITAL MARKETS SANTANDER GLOBAL BANKING & SOCIÉTÉ GÉNÉRALE CORPORATE & MARKETS INVESTMENT BANKING THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND UBS INVESTMENT BANK An investment in Notes issued under the Programme involves certain risks. For information on this see “Risk Factors”. The date of this Information Memorandum is 15 August 2013 Overview of the Programme Shell International Finance B.V. (“Shell Finance”) and Royal Dutch Shell plc (“Royal Dutch Shell”) (each an “Issuer” and, together, the “Issuers”) have established a programme (the “Programme”) to facilitate the issuance of notes and other debt securities (the “Notes”) guaranteed (in the case of Notes issued by Shell Finance) by Royal Dutch Shell (the “Guarantor”). The aggregate principal amount of Notes outstanding and guaranteed will not at any time exceed U.S.$25,000,000,000 (or the equivalent in other currencies). Application has been made to the Financial Conduct Authority in its capacity as competent authority (the “UK Listing Authority”) for Notes issued under the Programme up to the expiry of 12 months from the date of this Information Memorandum to be admitted to the official list of the UK Listing Authority (the “Official List”) and to the London Stock Exchange plc (the “London Stock Exchange”) for such Notes to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s regulated market. -

Premises Licence

London Borough of Lambeth Public Protection 2 Herne Hill Road London SE24 0AU Tel: 020 7926 6108 Licensing Act 2003 Premises Licence Premises Licence Number 07/00591/PREMLI/826 Part 1 – Premises Details Postal address of premises, or if none, ordnance survey map reference or description, including Post Town, Post Code Queen Elizabeth Hall Queen Elizabeth Hall And Purcell Room South Bank London SE1 8XX Telephone number Where the licence is time limited the dates - The opening hours of the premises Monday 07:00 - 02:30 Tuesday 07:00 - 02:30 Wednesday 07:00 - 02:30 Thursday 07:00 - 02:30 Friday 07:00 - 02:30 Saturday 07:00 - 02:30 Sunday 07:00 - 02:30 Licensable activities authorised by the licence Boxing or Wrestling Entertainment Films Performances of Dance Supply of Alcohol Entertainment of similar description Indoor Sporting Events 1 Live Music Late Night Refreshment Provision of facilities for Making Music Music and Dance of similar description Recorded Music Plays Provision of facilities for Dancing Times the licence authorises the carrying out of licensable activities Boxing or Wrestling Entertainment Monday - Sunday 07:00 - 02:30 New Year's Eve - from the start of permitted hours on New Year's Eve to the end of permitted hours on New Years Day The applicant would like the flexibility to permit occasional boxing and wrestling entertainment out side regular hours up to a maximum of 12 additional times per annum, providing both the police and local authority are given at least 14 days notice beforehand. This is in addition to applicant’s right to give 12 temporary Event Notices per annum for the premises. -

250 City Road

Lifestyle GUIDE Luxury GUIDE FROM TO As a global city, London has something for everyone. It is one of the worlds most visited cities: for its history and culture, arts and fine food, the experience is unrivalled and all on your doorstep at City Road. London’s cultural dynamism attracts visitors and residents alike from every country. In 2021, London was named the rich person’s city of choice for lifestyle – for its abundance of Michelin-starred restaurants, opera houses and theatres, universities, sports and shopping facilities. London has also overtaken New York to the top spot, with the highest concentration of ‘high net worth individuals’ in the world,* making it a haven for those seeking the Z pinnacle of luxury lifestyle. In this guide, we’ve compiled some of the most prestigious places to dine, socialise, shop and enjoy life in this unique capital city, as well as their proximity to City Road. *Source: Knight Frank 2021 Wealth Report. 2 London 2021 Camden Town ESSEX ROAD Olympic Park Barnsbury Rosemary Gardens Bernhard Westfield Gardens Islington Stratford City St. John’s Wood University of the Dalston PUDDING Queen’s Arts London MILL LANE Park To Luton Airport Shoreditch Victoria Park Central St Martins Park QUEEN’S PARK Haggerston King’s Cross Park 1 ANGEL NE KING’S CROSS ZO ST PANCRAS ST PANCRAS Sadler's Wells HOXTON Maida Vale Regent’s Park INTERNATIONAL Theatre Kensal Green Clerkenwell BOW CHURCH College Park Meath BOW RD EUSTON City University Gardens London OLD STREET London Business Shoreditch Mile End University College -

Press Release Hayward Gallery Welcomes a Series of New Outdoor

Press Release Date: Tuesday 06 July Contact: [email protected] Images: downloadable HERE This press release is available in a variety of accessible formats. Please email [email protected] Hayward Gallery welcomes a series of new outdoor commissions in partnership with the Bagri Foundation Credits (from left): Hayward Gallery exterior © Pete Woodhead; Hayward Gallery Billboard showing Salman Toor’s Music Room © Rob Harris; Jeppe Hein's Appearing Rooms outside Queen Elizabeth Hall. A three-year partnership, announced today, between the Hayward Gallery and the Bagri Foundation will brinG a series of new outdoor art commissions to the Southbank Centre. Aimed at providinG artists from or inspired by Asia and its diaspora with the opportunity to create a prominent public commission, this new initiative is the latest addition to a growing programme of outdoor art installations and exhibitions across the Southbank Centre’s iconic site. The BaGri Foundation commission, launchinG next month, will take place every summer until 2023. Founded with roots in education, the Bagri Foundation is dedicated to realising artistic interpretations and ideas that weave traditional Asian culture with contemporary thinkinG. This mission underpins the three-year partnership between the Foundation and the Hayward Gallery, brinGinG new artistic encounters to the General public. Each year, an artist will be commissioned to produce a site-specific work that invites visitors to London’s Southbank Centre to experience contemporary art in a unique and unexpected space beyond the gallery. The first commission launches in AuGust 2021 with a larGe-scale installation by collective Slavs and Tatars. With a focus devoted to an area East of the former Berlin Wall and West of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia, Slavs and Tatars’ practice questions understandings of language, ritual and identity through a blend of pop aesthetics, cultural traditions and overlooked histories. -

JS Journal Dec 1967

JSJOURIMAL. December/67 House magazine of J Sainsbury Ltd Halesowen Our new branch in this growing IMEWS AND township to the west of Birmingham opened November 14. Shopping area is 5.700 square feet, with ten checkouts. The dining room at first floor level looks out on a raised walk-way around the central area. Lower picture, shows one of our new refrigerated display cabinets with two-tier shelf. Manager at Halesowen is Mr. W. R. Yeates who joined the 1 firm in 1950 was first appointed manager at Collier Row in 1962 and came from Solihull for the opening of this branch. Below him is Mr. R. Sowerby, Assistant Manager, then Mr. C. Harvey, Deputy Manager. Bottom picture left is of Mr. R. Simpson, Assistant Manager. Immediately © standard tngu&r. below is the Head Butcher, Mr. C. Downey. First Clerk is Mrs. A. Barton. SSoTsa *"" § Standarc Kingston Kingston has a new self-service The new shop, opened on October John of Runnymede fame granted branch standing next to a 24, has 17 checkouts and a the town a charter in 1209 which multistorey car park in Eden shopping area of 9,200 square was extended by several monarchs Street which is only a minute's feet. Despite the contemporary and is still extant. walk from Clarence Street where look of our picture Kingston is an On the opposite page is a view of we have now closed two branches, ancient market town that still some of our new transparent egg 57b opened in 1905 and 97 holds weekly markets. -

“How Do We Live?” Housing Workshop / London 2019 11Th April — 18Th April 2019 Jocelyn Froimovich, Johanna Muszbek University of Liverpool in London

“How Do We Live?” Housing Workshop / London 2019 11th April — 18th April 2019 Jocelyn Froimovich, Johanna Muszbek University of Liverpool in London Housing design never starts afresh; housing design operates through variation, iteration, and/or mutation of prior examples. The series of workshops “How do we live?” venture into a typological investigation, with the expectation that types can provide a framework to deal with complex urban variables. By understanding the particulars in the production of a housing type, the architect can manipulate and reorganise—invent. This workshop will discuss housing types, exemplary of a particular city in its making. By looking at past exemplary projects ant today’s market offer, the goal is to observe, analyse, participate and hopefully interfere in the production system of the urban. Rather than dismissing examples of the current housing offer as “bastard” architecture, it is assumed that these housing types portray specific subjects, their living and urban conditions; the politics, policies, and socio economic factors that lead into developing a particular urban setting. Thus, the goal of the studio is to design new housing types that expand the existing housing repertoire. These new types will respond to current and future lifestyles and contribute to resolve specific urban demands. The question for this workshop is: what defines the housing crisis of London today? By forcing the notion of crisis as a methodology, each student will question a specific London housing type and propose alternative designs for each of them. For this workshop, the notion of “crisis” will be used as an operative term. “Crisis” is understood as a turning point, a time when a difficult or important decision must be made.