Viewpoints Henry Lambright.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curiosity's Candidate Field Site in Gale Crater, Mars

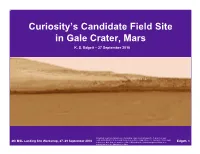

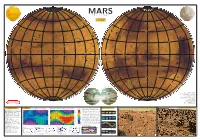

Curiosity’s Candidate Field Site in Gale Crater, Mars K. S. Edgett – 27 September 2010 Simulated view from Curiosity rover in landing ellipse looking toward the field area in Gale; made using MRO CTX stereopair images; no vertical exaggeration. The mound is ~15 km away 4th MSL Landing Site Workshop, 27–29 September 2010 in this view. Note that one would see Gale’s SW wall in the distant background if this were Edgett, 1 actually taken by the Mastcams on Mars. Gale Presents Perhaps the Thickest and Most Diverse Exposed Stratigraphic Section on Mars • Gale’s Mound appears to present the thickest and most diverse exposed stratigraphic section on Mars that we can hope access in this decade. • Mound has ~5 km of stratified rock. (That’s 3 miles!) • There is no evidence that volcanism ever occurred in Gale. • Mound materials were deposited as sediment. • Diverse materials are present. • Diverse events are recorded. – Episodes of sedimentation and lithification and diagenesis. – Episodes of erosion, transport, and re-deposition of mound materials. 4th MSL Landing Site Workshop, 27–29 September 2010 Edgett, 2 Gale is at ~5°S on the “north-south dichotomy boundary” in the Aeolis and Nepenthes Mensae Region base map made by MSSS for National Geographic (February 2001); from MOC wide angle images and MOLA topography 4th MSL Landing Site Workshop, 27–29 September 2010 Edgett, 3 Proposed MSL Field Site In Gale Crater Landing ellipse - very low elevation (–4.5 km) - shown here as 25 x 20 km - alluvium from crater walls - drive to mound Anderson & Bell -

Executive Branch

EXECUTIVE BRANCH THE PRESIDENT BARACK H. OBAMA, Senator from Illinois and 44th President of the United States; born in Honolulu, Hawaii, August 4, 1961; received a B.A. in 1983 from Columbia University, New York City; worked as a community organizer in Chicago, IL; studied law at Harvard University, where he became the first African American president of the Harvard Law Review, and received a J.D. in 1991; practiced law in Chicago, IL; lecturer on constitutional law, University of Chicago; member, Illinois State Senate, 1997–2004; elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 2004; and served from January 3, 2005, to November 16, 2008, when he resigned from office, having been elected President; family: married to Michelle; two children: Malia and Sasha; elected as President of the United States on November 4, 2008, and took the oath of office on January 20, 2009. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500 Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), 17th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500, phone (202) 456–1414, http://www.whitehouse.gov The President of the United States.—Barack H. Obama. Special Assistant to the President and Personal Aide to the President.— Anita Decker Breckenridge. Director of Oval Office Operations.—Brian Mosteller. OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT phone (202) 456–1414 The Vice President.—Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Bruce Reed, EEOB, room 276, 456–9000. Deputy Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff to Dr. Jill Biden.—Sheila Nix, EEOB, room 200, 456–7458. -

Minutes of the January 25, 2010, Meeting of the Board of Regents

MINUTES OF THE JANUARY 25, 2010, MEETING OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS ATTENDANCE This scheduled meeting of the Board of Regents was held on Monday, January 25, 2010, in the Regents’ Room of the Smithsonian Institution Castle. The meeting included morning, afternoon, and executive sessions. Board Chair Patricia Q. Stonesifer called the meeting to order at 8:31 a.m. Also present were: The Chief Justice 1 Sam Johnson 4 John W. McCarter Jr. Christopher J. Dodd Shirley Ann Jackson David M. Rubenstein France Córdova 2 Robert P. Kogod Roger W. Sant Phillip Frost 3 Doris Matsui Alan G. Spoon 1 Paul Neely, Smithsonian National Board Chair David Silfen, Regents’ Investment Committee Chair 2 Vice President Joseph R. Biden, Senators Thad Cochran and Patrick J. Leahy, and Representative Xavier Becerra were unable to attend the meeting. Also present were: G. Wayne Clough, Secretary John Yahner, Speechwriter to the Secretary Patricia L. Bartlett, Chief of Staff to the Jeffrey P. Minear, Counselor to the Chief Justice Secretary T.A. Hawks, Assistant to Senator Cochran Amy Chen, Chief Investment Officer Colin McGinnis, Assistant to Senator Dodd Virginia B. Clark, Director of External Affairs Kevin McDonald, Assistant to Senator Leahy Barbara Feininger, Senior Writer‐Editor for the Melody Gonzales, Assistant to Congressman Office of the Regents Becerra Grace L. Jaeger, Program Officer for the Office David Heil, Assistant to Congressman Johnson of the Regents Julie Eddy, Assistant to Congresswoman Matsui Richard Kurin, Under Secretary for History, Francisco Dallmeier, Head of the National Art, and Culture Zoological Park’s Center for Conservation John K. -

STANDING COMMITTEES of the HOUSE Agriculture

STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE [Democrats in roman; Republicans in italic; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface] [Room numbers beginning with H are in the Capitol, with CHOB in the Cannon House Office Building, with LHOB in the Longworth House Office Building, with RHOB in the Rayburn House Office Building, with H1 in O’Neill House Office Building, and with H2 in the Ford House Office Building] Agriculture 1301 Longworth House Office Building, phone 225–2171, fax 225–8510 http://agriculture.house.gov meets first Wednesday of each month Collin C. Peterson, of Minnesota, Chair Tim Holden, of Pennsylvania. Bob Goodlatte, of Virginia. Mike McIntyre, of North Carolina. Terry Everett, of Alabama. Bob Etheridge, of North Carolina. Frank D. Lucas, of Oklahoma. Leonard L. Boswell, of Iowa. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. Joe Baca, of California. Robin Hayes, of North Carolina. Dennis A. Cardoza, of California. Timothy V. Johnson, of Illinois. David Scott, of Georgia. Sam Graves, of Missouri. Jim Marshall, of Georgia. Jo Bonner, of Alabama. Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, of South Dakota. Mike Rogers, of Alabama. Henry Cuellar, of Texas. Steve King, of Iowa. Jim Costa, of California. Marilyn N. Musgrave, of Colorado. John T. Salazar, of Colorado. Randy Neugebauer, of Texas. Brad Ellsworth, of Indiana. Charles W. Boustany, Jr., of Louisiana. Nancy E. Boyda, of Kansas. John R. ‘‘Randy’’ Kuhl, Jr., of New York. Zachary T. Space, of Ohio. Virginia Foxx, of North Carolina. Timothy J. Walz, of Minnesota. K. Michael Conaway, of Texas. Kirsten E. Gillibrand, of New York. Jeff Fortenberry, of Nebraska. Steve Kagen, of Wisconsin. Jean Schmidt, of Ohio. -

Tentative Lists Submitted by States Parties As of 15 April 2021, in Conformity with the Operational Guidelines

World Heritage 44 COM WHC/21/44.COM/8A Paris, 4 June 2021 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Extended forty-fourth session Fuzhou (China) / Online meeting 16 – 31 July 2021 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8A. Tentative Lists submitted by States Parties as of 15 April 2021, in conformity with the Operational Guidelines SUMMARY This document presents the Tentative Lists of all States Parties submitted in conformity with the Operational Guidelines as of 15 April 2021. • Annex 1 presents a full list of States Parties indicating the date of the most recent Tentative List submission. • Annex 2 presents new Tentative Lists (or additions to Tentative Lists) submitted by States Parties since 16 April 2019. • Annex 3 presents a list of all sites included in the Tentative Lists of the States Parties to the Convention, in alphabetical order. Draft Decision: 44 COM 8A, see point II I. EXAMINATION OF TENTATIVE LISTS 1. The World Heritage Convention provides that each State Party to the Convention shall submit to the World Heritage Committee an inventory of the cultural and natural sites situated within its territory, which it considers suitable for inscription on the World Heritage List, and which it intends to nominate during the following five to ten years. Over the years, the Committee has repeatedly confirmed the importance of these Lists, also known as Tentative Lists, for planning purposes, comparative analyses of nominations and for facilitating the undertaking of global and thematic studies. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

Extraformational Sediment Recycling on Mars Kenneth S

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Extraformational sediment recycling on Mars Kenneth S. Edgett1, Steven G. Banham2, Kristen A. Bennett3, Lauren A. Edgar3, Christopher S. Edwards4, Alberto G. Fairén5,6, Christopher M. Fedo7, Deirdra M. Fey1, James B. Garvin8, John P. Grotzinger9, Sanjeev Gupta2, Marie J. Henderson10, Christopher H. House11, Nicolas Mangold12, GEOSPHERE, v. 16, no. 6 Scott M. McLennan13, Horton E. Newsom14, Scott K. Rowland15, Kirsten L. Siebach16, Lucy Thompson17, Scott J. VanBommel18, Roger C. Wiens19, 20 20 https://doi.org/10.1130/GES02244.1 Rebecca M.E. Williams , and R. Aileen Yingst 1Malin Space Science Systems, P.O. Box 910148, San Diego, California 92191-0148, USA 2Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, South Kensington, London SW7 2AZ, UK 19 figures; 1 set of supplemental files 3U.S. Geological Survey, Astrogeology Science Center, 2255 N. Gemini Drive, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001, USA 4Department of Astronomy and Planetary Science, Northern Arizona University, P.O. Box 6010, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011, USA CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] 5Department of Planetology and Habitability, Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), M-108, km 4, 28850 Madrid, Spain 6Department of Astronomy, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853, USA 7 CITATION: Edgett, K.S., Banham, S.G., Bennett, K.A., Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, The University of Tennessee, 1621 Cumberland Avenue, 602 Strong Hall, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996-1410, USA 8 Edgar, L.A., Edwards, C.S., Fairén, A.G., Fedo, C.M., National Aeronautics -

Executive Branch

EXECUTIVE BRANCH THE PRESIDENT BARACK H. OBAMA, Senator from Illinois and 44th President of the United States; born in Honolulu, Hawaii, August 4, 1961; received a B.A. in 1983 from Columbia University, New York City; worked as a community organizer in Chicago, IL; studied law at Harvard University, where he became the first African American president of the Harvard Law Review, and received a J.D. in 1991; practiced law in Chicago, IL; lecturer on constitutional law, University of Chicago; member, Illinois State Senate, 1997–2004; elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 2004; and served from January 3, 2005, to November 16, 2008, when he resigned from office, having been elected President; family: married to Michelle; two children: Malia and Sasha; elected as President of the United States on November 4, 2008, and took the oath of office on January 20, 2009. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500 Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), 17th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500, phone (202) 456–1414, http://www.whitehouse.gov The President of the United States.—Barack H. Obama. Personal Aide to the President.—Katherine Johnson. Special Assistant to the President and Personal Aide.—Reginald Love. OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT phone (202) 456–1414 The Vice President.—Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Bruce Reed, EEOB, room 202, 456–9000. Deputy Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Alan Hoffman, EEOB, room 202, 456–9000. Counsel to the Vice President.—Cynthia Hogan, EEOB, room 246, 456–3241. -

Election Insight 2020

ELECTION INSIGHT 2020 “This isn’t about – yeah, it is about me, I guess, when you think about it.” – President Donald J. Trump Kenosha Wisconsin Regional Airport Election Eve. 1 • Election Insight 2020 Contents 04 … Election Results on One Page 06 … Biden Transition Team 10 … Potential Biden Administration 2 • Election Insight 2020 Election Results on One Page 3 • Election Insight 2020 DENTONS’ DEMOCRATS Election Results on One Page “The waiting is the hardest part.” Election results as of 1:15 pm November 11th – Tom Petty Top Line Biden declared by multiple news networks to be America’s next president. Biden’s Pennsylvania win puts him over 270. Georgia and North Carolina not yet called. Biden narrowly leads in GA while Trump leads in NC. Trump campaign seeks recounts in GA and Wisconsin and files multiple lawsuits seeking to overturn the election results in states where Biden has won. Two January 5, 2021 runoff elections in Georgia will determine Senate control. Senator Mitch McConnell will remain Majority Leader and divided government will continue, complicating the prospects for Biden’s legislative agenda, unless Democrats win both runoff s. Democrats retain their House majority but Republicans narrow the Democrats’ margin with a net pickup of six seats. Incumbents Losing Reelection • Sen. Doug Jones (D-AL) • Rep. Harley Rouda (D-CA-48) • Rep. Xochitl Torres Small (D-NM-3) • Sen. Martha McSally (R-AZ) • Rep. Debbie Mucarsel-Powell (D-FL-26) • Rep. Max Rose (D-NY-11) • Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO) • Rep. Donna Shalala (D-FL-27) • Rep. Kendra Horn (D-OK-5) • Rep. -

In Pdf Format

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

Pplanetary Materials Research At

N. L. CHABOT ET AL . Planetary Materials Research at APL Nancy L. Chabot, Catherine M. Corrigan, Charles A. Hibbitts, and Jeffrey B. Plescia lanetary materials research offers a unique approach to understanding our solar system, one that enables numerous studies and provides insights that are not pos- sible from remote observations alone. APL scientists are actively involved in many aspects of planetary materials research, from the study of Martian meteorites, to field work on hot springs and craters on Earth, to examining compositional analogs for asteroids. Planetary materials research at APL also involves understanding the icy moons of the outer solar system using analog materials, conducting experiments to mimic the conditions of planetary evolution, and testing instruments for future space missions. The diversity of these research projects clearly illustrates the abundant and valuable scientific contributions that the study of planetary materials can make to Pspace science. INTRODUCTION In most space science and astronomy fields, one is When people think of planetary materials, they com- limited to remote observations, either from telescopes monly think of samples returned by space missions. Plan- or spacecraft, to gather data about celestial objects and etary materials available for study do include samples unravel their origins. However, for studying our solar returned by space missions, such as samples of the Moon system, we are less limited. We have samples of plan- returned by the Apollo and Luna missions, comet dust etary materials from multiple bodies in our solar system. collected by the Stardust mission, and implanted solar We can inspect these samples, examine them in detail wind ions collected by the Genesis mission. -

Orszag to Depart OMB Director Post | 1

Orszag to Depart OMB Director Post | 1 Orszag to Depart OMB Director Post By Editor Test Wed, Jun 30, 2010 “Basically, the OMB Director is a brutal job and subject to quick burnout," commented one political blogger. Peter R. Orszag, who brought a strong retirement perspective to his job as budget director in the Obama administration, will leave the White House later this summer, several news organizations reported last week. “Basically, the OMB Director is a brutal job and subject to quick burnout. I wouldn’t read any more into this than that,” wrote David Dayen on the newsblog, firedoglake, by way of explanation. Orszag’s impending departure was first rumored last April. According to the Washington Post, likely candidates for appointment to the post of director of the Office of Management and Budget include (in order of probability): Laura D. Tyson, former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers in the Clinton administration who currently teaches at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. John Berry, head of the Office of Personnel Management. Rob Nabors, who served as Orszag’s deputy before joining White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel’s office to focus on special projects. Gene Sperling, a senior adviser to Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner and a top economic official in the Clinton administration. Robert Greenstein, director of the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. He served on the Bipartisan Commission on Entitlement and Tax Reform during the Clinton administration. Byron Dorgan, North Dakota’s retiring Democratic senator. Jeffrey Liebman, an economist with expertise on poverty, pensions and Social Security.