Growing Risk: Addressing the Invasive Potential of Bioenergy Feedstocks 1 Growing Risk Addressing the Invasive Potential of Bioenergy Feedstocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of the Combustion Characteristics of Four Perennial Energy Crops (Arundo Donax, Cynara Cardunculus, Miscanthus X Giganteus and Panicum Virgatum)

2nd World Conference on Biomass for Energy, Industry and Climate Protection, 10-14 May 2004, Rome, Italy EVALUATION OF THE COMBUSTION CHARACTERISTICS OF FOUR PERENNIAL ENERGY CROPS (ARUNDO DONAX, CYNARA CARDUNCULUS, MISCANTHUS X GIGANTEUS AND PANICUM VIRGATUM) Jonas Dahl & Ingwald Obernberger Institute of Resource Efficient and Sustainable Systems, Graz University of Technology, Inffeldgasse 25, A - 8010 Graz, Austria, Tel.: +43 (0)316 481300, Fax: +43 (0)316 481300 4; E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The perennial crops giant reed, switchgrass, miscanthus and cardoon were investigated in laboratory- scale and pilot-scale combustion test runs. Laboratory-scale test runs were conducted in a fixed bed pot reactor monitoring the temperature in the fuel bed and the release of gaseous components while pilot-scale test runs where conducted in a 150 kWth rotating grate fired combustion plant measuring formed emissions of CO, NOX, SO2, HCl, and particulates as well as performing deposit probe measurements. The results revealed that the high concentration of ash and slag forming elements such as Si, K and Ca cause severe problems regarding slagging if not specially considered during combustion. Moreover, high concentrations of N are another challenge regarding measures in order to avoid high emissions of NOx. Moreover, also HCl and SO2 emissions are considerably higher compared to wood fuels due to the higher concentrations of Cl and S in these fuels. Keywords: biomass characteristics, biomass conversion, cynara cardonculus, giant reed, switchgrass, miscanthus 1 INTRODUCTION combustion unit (nominal boiler capacity 150 kWth) were carried out with larger amounts (2-4 tons) of Due to the limited availability of wood fuels, in pelletised switch grass and chopped giant reed and southern Europe, high yield energy crops could give an chopped miscanthus (MI). -

Is Biodiesel As Attractive an Economic Alternative As Ethanol?

PURDUE EXTENSION Bio ID-341 Fueling America ThroughE Renewablenergy Resources Is Biodiesel as Attractive an Economic Alternative as Ethanol? Allan Gray Department of Agricultural Economics Purdue University What Is Biodiesel? and as a lubricant additive to low sulfur diesel Biodiesel is a renewable fuel alternative to fuel. A change in environmental laws associ- standard on-road diesel. Biodiesel is made ated with sulfur emissions from diesel has from plant oils, such as soybean oil; animal caused the industry to move from a standard fat from slaughter facilities; or used greases. number 2 diesel to a cleaner burning number Seventy-three percent of biodiesel produced 1 diesel with much lower sulfur emission. in the United States comes from soybean oil. The remaining 27% is produced from the However, number 1 diesel fuel has a much other feedstocks. lower lubricity than number 2 diesel, causing additional wear on diesel engines. By blending The ability to use a variety of feedstocks to number 1 diesel with at least 2% biodiesel, the make biodiesel differentiates this biofuel mar- lubricity properties of the fuel can be the same ket from the current ethanol market, which as number 2 diesel fuel. And, because biodie- is dominated by corn in the U.S. and sugar sel contains only small traces of sulfur when in South America. The ability to use various burned, the sulfur emission standards can still feedstocks is one of the reasons that biodiesel be met. production facilities are not as concentrated in the Midwest as ethanol plants. In 2005, approximately 75 million gallons of biodiesel were produced in 65 plants scattered How Is Biodiesel Used? across the United States (Figure 1). -

Advanced Biofuel Policies in Select Eu Member States: 2018 Update

© INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON CLEAN TRANSPORTATION POLICY UPDATE NOVEMBER 2018 ADVANCED BIOFUEL POLICIES IN SELECT EU MEMBER STATES: 2018 UPDATE This policy update provides details on the latest measures that select European ICCT POLICY UPDATES Union (EU) member states, namely Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, SUMMARIZE Sweden, and the United Kingdom, are taking to support advanced alternative fuels. REGULATORY AND OTHER EU POLICY BACKGROUND DEVELOPMENTS In 2018, the European Union (EU) set its climate and energy objectives for 2030. RELATED TO CLEAN They included a greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction of at least 40% and a minimum of a TRANSPORTATION 32% share of renewable energy consumption across all sectors.1 GHG emissions in the WORLDWIDE. European transportation sector have declined by only 3.8% since 2008, compared to an 18% decrease, or more, in all other sectors, indicating that the decarbonization of transportation should be a priority for the future.2 Biofuels are one of the options considered to increase renewable energy and decrease the carbon intensity of the transportation sector. Through the use of directives and national legislation, the EU has incentivized both the adoption of conventional food-based biofuels and advanced biofuels, which are made from non-food feedstocks. Such incentives date to 2009, when the EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED) mandated that by 2020, 10% of energy used in the transportation sector should come from renewable energy sources (RES).3 In 2015, the RED was 1 Jacopo Giuntoli, Final recast Renewable Energy Directive for 2021-2030 in the European Union, (ICCT: Washington, DC, 2018), https://www.theicct.org/publications/final-recast-renewable-energy-directive- 2021-2030-european-union 2 EUROSTAT (Greenhouse gas emissions by source sector (env_air_gge), accessed November 2018), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat. -

Spring Camelina Production Guide 2009 DEC.Indd

SPRING CAMELINA PRODUCTION GUIDE For the Central High Plains December 2009 Central High Plains Produced by Blue Sun Energy with the support of Advancing Colorado’s Renewable Energy (ACRE) Ryan M. Lafferty, Charlie Rife and Gus Foster 1 2 INTRODUCTION Camelina, [Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz, Brassicaceae] This document is available for purchase at the AAFCO is an old world crop newly introduced to the semiarid west of website. Research is ongoing and increased feeding levels the United States. Camelina is promising new spring-sown are expected to be established in the future. rotation crop due to its excellent seedling frost tolerance, a short production cycle (60-90 days) and resistance to flea Camelina is adapted to marginal growing conditions. beetles. Camelina has a high oil content (~35% oil) and Preliminary water use efficiency research conducted in improved drought tolerance and water use efficiency (yield Akron, CO at the Great Plains Research Center indicates that vs. evapotranspiration (ET)) when compared to other oilseed it has the highest water use efficiency of the tested oilseed crops. crops (canola, juncea, and sunflowers). Camelina is planted early spring (March) and is harvested in early to mid July. Camelina is a member of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae) Camelina is adapted (low-water use and short production family. Brassicaceae is comprised of about 350 genera and cycle) to fit into the winter wheat based crop rotation systems 3000 species. Important crops in this family include canola/ of the semiarid (10-15 inches precipitation) High Plains. rapeseed, (Brassica napus and B. rapa); mustards, (B. juncea; Sinapus alba; B. -

A Chromosome-Scale Assembly of Miscanthus Sinensis

1/23/2018 A chromosome-scale assembly allows genome-scale analysis A Chromosome-Scale Assembly • Genome assembly and annotation update of Miscanthus sinensis • Andropogoneae relatedness Therese Mitros University of California Berkeley • Miscanthus-specific duplication and ancestry • Miscanthus ancestry and introgression Miscanthus genome assembly is chromosome scale • A doubled-haploid accession of Miscanthus sinensis was created by Katarzyna Glowacka • Illumina sequencing to 110X depth • Illumina mate-pairs of 2kb, 5kb, fosmid-end • Chicago and HiC libraries from Dovetail Genomics • 2.079 GB assembled (11% gap) with 91% of genome assembly bases in the known 19 Miscanthus chromosomes HiC contact map Dovetail assembly agrees with genetic map RADseq markers from 3 M. ) sinensis maps and one M. sinensis cM ( x M. sacchariflorus map (H. Dong) Of 6377 64-mer markers from these maps genetic map 4298 map well to the M. sinensis DH1 assembly and validate the Dovetail assembly combined Miscanthus Miscanthus sequence assembly 1 1/23/2018 Annotation summary • 67,789 Genes, 11,489 with alternate transcripts • 53,312 show expression over 50% of their lengths • RNA-seq libraries from stem, root, and leaves sampled over multiple growing seasons • Small RNA over same time points • Available at phytozome • https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#!info?alias=Org_Msinensis_er Miscanthus duplication and retention relative Small RNA to Sorghum miRNA putative_miRNA 0.84% 0.14% 369 clusters miRBase annotated miRNA 61 clusters phasiRNA 43 clusters 1.21% -

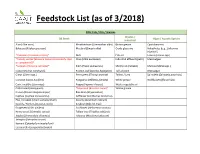

Feedstock List (As of 3/2018)

Feedstock List (as of 3/2018) FOG: Fats / Oils / Greases Wastes / Oil Seeds Algae / Aquatic Species Industrial Aloe (Aloe vera) Meadowfoam (Limnanthes alba) Brown grease Cyanobacteria Babassu (Attalea speciosa) Mustard (Sinapis alba) Crude glycerine Halophytes (e.g., Salicornia bigelovii) *Camelina (Camelina sativa)* Nuts Fish oil Lemna (Lemna spp.) *Canola, winter (Brassica napus[occasionally rapa Olive (Olea europaea) Industrial effluent (palm) Macroalgae or campestris])* *Carinata (Brassica carinata)* Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Shrimp oil (Caridea) Mallow (Malva spp.) Castor (Ricinus communis) Peanut, Cull (Arachis hypogaea) Tall oil pitch Microalgae Citrus (Citron spp.) Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) Tallow / Lard Spirodela (Spirodela polyrhiza) Coconut (Cocos nucifera) Pongamia (Millettia pinnata) White grease Wolffia (Wolffia arrhiza) Corn, inedible (Zea mays) Poppy (Papaver rhoeas) Waste vegetable oil Cottonseed (Gossypium) *Rapeseed (Brassica napus)* Yellow grease Croton megalocarpus Oryza sativa Croton ( ) Rice Bran ( ) Cuphea (Cuphea viscossisima) Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) Flax / Linseed (Linum usitatissimum) Sesame (Sesamum indicum) Gourds / Melons (Cucumis melo) Soybean (Glycine max) Grapeseed (Vitis vinifera) Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) Hemp seeds (Cannabis sativa) Tallow tree (Triadica sebifera) Jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis) Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) Jatropha (Jatropha curcas) Calophyllum inophyllum Kamani ( ) Lesquerella (Lesquerella fenderi) Cellulose Woody Grasses Residues Other Types: Arundo (Arundo donax) Bagasse -

Camelina Sativa, a Montana Omega-3 and Fuel Crop* Alice L

Reprinted from: Issues in new crops and new uses. 2007. J. Janick and A. Whipkey (eds.). ASHS Press, Alexandria, VA. Camelina sativa, A Montana Omega-3 and Fuel Crop* Alice L. Pilgeram, David C. Sands, Darrin Boss, Nick Dale, David Wichman, Peggy Lamb, Chaofu Lu, Rick Barrows, Mathew Kirkpatrick, Brian Thompson, and Duane L. Johnson Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz, (Brassicaceae), commonly known as false flax, leindotter and gold of pleasure, is a fall or spring planted annual oilcrop species (Putman et al. 1993). This versatile crop has been cultivated in Europe since the Bronze Age. Camelina seed was found in the stomach of Tollund man, a 4th century BCE mummy recovered from a peat bog in Denmark (Glob 1969). Anthropologists postulate that the man’s last meal had been a soup made from vegetables and seeds including barley, linseed, camelina, knotweed, bristle grass, and chamomile. The Romans used camelina oil as massage oil, lamp fuel, and cooking oil, as well as the meal for food or feed. Camelina, like many Brassicaceae, germinates and emerges in the early spring, well before most cereal grains. Early emergence has several advantages for dryland production including efficient utiliza- tion of spring moisture and competitiveness with common weeds. In response to the resurgent interest in oil crops for sustainable biofuel production, the Montana State Uni- versity (MSU) Agricultural Research Centers have conducted a multi-year, multi-specie oilseed trial. This trial included nine different oilseed crops (sunflower, safflower, soybean, rapeseed, mustard, flax, crambe, canola, and camelina). Camelina sativa emerged from this trial as a promising oilseed crop for production across Montana and the Northern Great Plains. -

Global Production of Second Generation Biofuels: Trends and Influences

GLOBAL PRODUCTION OF SECOND GENERATION BIOFUELS: TRENDS AND INFLUENCES January 2017 Que Nguyen and Jim Bowyer, Ph. D Jeff Howe, Ph. D Steve Bratkovich, Ph. D Harry Groot Ed Pepke, Ph. D. Kathryn Fernholz DOVETAIL PARTNERS, INC. Global Production of Second Generation Biofuels: Trends and Influences Executive Summary For more than a century, fossil fuels have been the primary source of a wide array of products including fuels, lubricants, chemicals, waxes, pharmaceuticals and asphalt. In recent decades, questions about the impacts of fossil fuel reliance have led to research into alternative feedstocks for the sustainable production of those products, and liquid fuels in particular. A key objective has been to use feedstocks from renewable sources to produce biofuels that can be blended with petroleum-based fuels, combusted in existing internal combustion or flexible fuel engines, and distributed through existing infrastructure. Given that electricity can power short-distance vehicle travel, particular attention has been directed toward bio-derived jet fuel and fuels used in long distance transport. This report summarizes the growth of second-generation biofuel facilities since Dovetail’s 2009 report1 and some of the policies that drive that growth. It also briefly discusses biofuel mandates and second-generation biorefinery development in various world regions. Second generation biorefineries are operating in all regions of the world (Figure 1), bringing far more favorable energy balances to biofuels production than have been previously realized. Substantial displacement of a significant portion of fossil-based liquid fuels has been demonstrated to be a realistic possibility. However, in the face of low petroleum prices, continuing policy support and investment in research and development will be needed to allow biofuels to reach their full potential. -

Herbicides for Management of Waterhyacinth in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, California

J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 58: 98–104 Herbicides for management of waterhyacinth in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, California JOHN D. MADSEN AND GUY B. KYSER* ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Waterhyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.)Solms)isa Waterhyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms) is a free- global aquatic weed. Although a number of herbicides floating, rosette-forming aquatic plant originally from such as 2,4-D and glyphosate effectively control this plant, South America (Pfingsten et al. 2017). It has been rated as additional herbicides need to be evaluated to address the world’s worst aquatic weed (Holm et al. 1977) and one of concerns for herbicide stewardship and environmental the world’s worst 100 invasive alien species (Lowe et al. restrictions on the use of herbicides in particular areas. 2000). The Invasive Species Specialist Group reports that, as Waterhyacinth has become a significant nuisance in the of the year 2000, it was reported in 50 countries on 5 Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta. The predominant continents (Lowe et al. 2000). Introduced to the United herbicides for management of waterhyacinth in the Delta States at the Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans have been 2,4-D and glyphosate. However, environmental in 1884, it spread rapidly throughout the southeastern restrictions related to irrigation water residues and United States soon thereafter and was documented to cause restrictions for preservation of endangered species are widespread navigation issues within 15 yr (Klorer 1909, prompting consideration of the new reduced-risk herbi- Penfound and Earle 1948, Williams 1980). The U.S. cides imazamox and penoxsulam. Two trials were per- Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation formed in floating quadrats in the Delta during the Service (USDA-NRCS) (2017) currently reports it for 23 summer of 2016. -

Giant Miscanthus Establishment

Giant Miscanthus Establishment Introduction Giant Miscanthus (Miscanthus x giganteus), a warm-season perennial grass originating in Southeast Asia from two ornamental grasses, M. sacchariflorus and M. sinensis, is a popular candidate crop for biomass production in the Midwestern United States. This sterile hybrid is high yielding with many benefits to the land including soil stabilization and carbon sequestration. Vegetative propagation methods are necessary since giant Miscanthus does not produce viable seed. Field Preparation A giant Miscanthus stand first begins with field seedbed preparation. To provide good soil to rhizome contact, Figure 1. Rhizome segments. Photo credit: Heaton Lab. the seedbed should be tilled to a 3- to 5-inch depth. Soil moisture is critical to proper establishment for early stage time after the first frost in the fall and before the last one in germination. If working with dry land, prepare your field just the spring. If not immediately replanted in a new field, they prior to planting for optimal soil moisture. Good soil contact should be kept moist and cool (37-40º F) in storage. Ideal is also critical, so conversely, don’t till when the land is wet rhizomes have two to three visible buds, are light colored, and clods will form. Nutrient (NPK) and lime applications and firm (Fig. 1). Smaller rhizomes or those that are soft to should be made to the field as necessary before planting, the touch will likely have lower emergence. following typical corn recommendations for the area. Giant Miscanthus does not have high nutrient requirements once RHIZOME PLANTING established, but fields last for 20-30 years, so it is important Specialized rhizome planters are becoming available that adequate nutrition be present at establishment. -

Effect of Salinity and Waterlogging on Growth and Survival of Salicornia Europaea L., and Inland Halophyte

Effect of Salinity and Waterlogging on Growth and Survival of Salicornia europaea L., an Inland Halophyte1 CAROLYN HOWES KEIFFER, BRIAN C. MCCARTFIY, AND IRWIN A. UNGAR, Department of Environmental and Plant Biology, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701 ABSTRACT. Salicornia europaea seedlings were exposed to various salinity and water depths for 11 weeks under controlled, growth chamber conditions. Weekly measurements were made of height, number of nodes, and number of branches per plant. Growth and survival of plants grown with the addition of NaCl were significantly greater (P <0.0001) than for plants which were not given a salt treatment. Although there were no significant (P >0.05) growth differences among plants under different water level conditions within the salt treatment group, plants which were grown without NaCl demonstrated significant decreases in growth in higher water levels, with the greatest growth occurring in the low water treatment group. All plants given a salt treatment survived until the end of the experiment. However, high mortality occurred among the plants that were not salt-treated, with all plants grown under waterlogged conditions dying by week six. The high mortality exhibited by this treatment group indicates that Salicornia, which is typically found in low marsh or inland salt marsh situations, was unable to overcome the combined stress of being continuously waterlogged in a freshwater environment. OHIO J. SCI. 94 (3): 70-73, 1994 INTRODUCTION matter and methane formation is the terminal process in The distribution of plant species in saline environments fresh water marshes (Van Diggelen 1991). Therefore, of inland North America is closely associated with soil plants living in saline waterlogged soils face four major water potentials and other factors influencing the level of problems: 1) inhibition of aerobic root respiration which salinity stress, including microtopography, precipitation, may interfere with the uptake and transport of nutrients and depth of the water table (Ungar et al. -

Bioenergy and Invasive Plants: Quantifying and Mitigating Future Risks

Invasive Plant Science and Management 2014 7:199–209 Bioenergy and Invasive Plants: Quantifying and Mitigating Future Risks Jacob N. Barney* The United States is charging toward the largest expansion of agriculture in 10,000 years with vast acreages of primarily exotic perennial grasses planted for bioenergy that possess many traits that may confer invasiveness. Cautious integration of these crops into the bioeconomy must be accompanied by development of best management practices and regulation to mitigate the risk of invasion posed by this emerging industry. Here I review the current status of United States policy drivers for bioenergy, the status of federal and state regulation related to invasion mitigation, and survey the scant quantitative literature attempting to quantify the invasive potential of bioenergy crops. A wealth of weed risk assessments are available on exotic bioenergy crops, and generally show a high risk of invasion, but should only be a first-step in quantifying the risk of invasion. The most information exists for sterile giant miscanthus, with preliminary empirical studies and demographic models suggesting a relatively low risk of invasion. However, most important bioenergy crops are poorly studied in the context of invasion risk, which is not simply confined to the production field; but also occurs in crop selection, harvest and transport, and feedstock storage. Thus, I propose a nested-feedback risk assessment (NFRA) that considers the entire bioenergy supply chain and includes the broad components of weed risk assessment, species distribution models, and quantitative empirical studies. New information from the NFRA is continuously fed back into other components to further refine the risk assessment; for example, empirical dispersal kernels are utilized in landscape-level species distribution models, which inform habitat invasibility studies.