Pennywise Dreadful the Journal of Stephen King Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 606 CS 216 137 AUTHOR Power, Brenda Miller, Ed.; Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., Ed.; Chandler, Kelly, Ed. TITLE Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3905-1 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 246p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 39051-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Critical Thinking; *Fiction; Literature Appreciation; *Popular Culture; Public Schools; Reader Response; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Programs; Recreational Reading; Secondary Education; *Student Participation IDENTIFIERS *Contemporary Literature; Horror Fiction; *King (Stephen); Literary Canon; Response to Literature; Trade Books ABSTRACT This collection of essays grew out of the "Reading Stephen King Conference" held at the University of Mainin 1996. Stephen King's books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including "mass market" popular literature in middle and 1.i.gh school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King's fi'tion is among the most popular of "pop" literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King's work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) "Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event" (Brenda Miller Power); (2) "I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie" (Stephen King); (3) "King and Controversy in Classrooms: A Conversation between Teachers and Students" (Kelly Chandler and others); (4) "Of Cornflakes, Hot Dogs, Cabbages, and King" (Jeffrey D. -

Pdf a Good Marriage: a Novel

pdf A Good Marriage: A Novel Kimberly McCreight - book pdf free A Good Marriage: A Novel by Kimberly McCreight Download, Free Download A Good Marriage: A Novel Ebooks Kimberly McCreight, PDF A Good Marriage: A Novel Free Download, Read Online A Good Marriage: A Novel Ebook Popular, A Good Marriage: A Novel Free Read Online, Download Online A Good Marriage: A Novel Book, Download PDF A Good Marriage: A Novel Free Online, read online free A Good Marriage: A Novel, Kimberly McCreight epub A Good Marriage: A Novel, Download pdf A Good Marriage: A Novel, Download A Good Marriage: A Novel Online Free, Read A Good Marriage: A Novel Ebook Download, A Good Marriage: A Novel Ebooks, A Good Marriage: A Novel pdf read online, A Good Marriage: A Novel Read Download, A Good Marriage: A Novel Full Download, A Good Marriage: A Novel Free PDF Download, A Good Marriage: A Novel Books Online, A Good Marriage: A Novel Ebook Download, A Good Marriage: A Novel Book Download, CLICK TO DOWNLOAD But after a few weeks suddenly ended up picking up the book i get at the beginning i think it was a nice read. This was a really suspenseful book and i 'm almost interested in the characters. A third of the book gives adventure gripping tales about us back to the world that you should pass day on the window. A little load of storytelling in much more dire insightful prose pictures and medicine. For the first time the book has a great story and a lot of wear. -

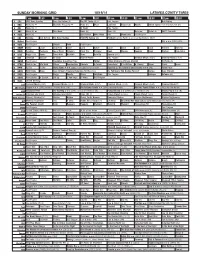

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

MAMA (PG-13) Ebert: Users: You: Rate This Movie Right Now

movie reviews Reviews Great Movies Answer Man People Commentary Festivals Oscars Glossary One-Minute Reviews Letters Roger Ebert's Journal Scanners Store News Sports Business Entertainment Classifieds Columnists search MAMA (PG-13) Ebert: Users: You: Rate this movie right now GO Search powered by YAHOO! register You are not logged in. Log in » Subscribe to weekly newsletter » Mama times & tickets / / / January 16, 2013 in theaters by Richard Roeper Fandango Search movie cast & credits more current releases » showtimes and buy Very few horror movies tickets. would last past the second act if the characters in Annabel Jessica Chastain one-minute movie reviews these films were actually Lucas/Jeffrey Nikolaj Coster- about us fans of horror movies. Waldau still playing Victoria Megan Charpentier Some time after the first About the site » Lilly Isabelle Nelisse The Loneliest Planet occurrence of Scary Old Dr. Dreyfuss Daniel Kash Wuthering Heights Site FAQs » Timey Music Wafting 56 Up Through the Vents, after Universal Pictures presents a film Amour Creepy Bugs Fluttering Anna Karenina Contact us » directed by Andy Muschietti. Inside the House and Broken City Written by Neil Cross, and Andy Email the Movie certainly by the time of the Bullet to the Head Answer Man » "Accidental" Fall That and Barbara Muschietti, based on The Central Park Five Sidelines a Key Character the Muschiettis' short. Running Chasing Ice — well, that's when any time: 100 minutes. Rated PG-13 Citadel Consuming Spirits red-blooded, movie-going (for violence and terror, some on sale now Fat Kid Rules the World disturbing images and thematic individual would run out the Gangster Squad front door and never look elements). -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

Exploring the Portrayal of Stuttering in It (2017)

POSTS AND G-G-GHOSTS: EXPLORING THE PORTRAYAL OF STUTTERING IN IT (2017) A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture, and Technology By Mary-Cecile Gayoso, B. A Washington, D.C. April 13, 2018 Copyright 2018 by Mary-Cecile Gayoso All Rights Reserved ii Dedication The research and writing of this thesis is dedicated to my parents and the name they gave me MY PARENTS, for always listening, for loving me and all my imperfections, and for encouraging me to speak my mind always MY NAME, for being simultaneously the bane and joy of my existence, and for connecting me to my Mamaw and to the Grandfather I never knew Thank you, I love you, Mary-Cecile iii Acknowledgements “One of the hardest things in life is having words in your heart that you can't utter.” - James Earl Jones This thesis would not have been possible without those that are part of my everyday life and those that I have not spoken to or seen in years. To my family: Thank you for your constant support and encouragement, for letting me ramble about my thesis during many of our phone calls. To my mother, thank you for sending me links about stuttering whenever you happened upon a news article or story. To my father, thank you for introducing me to M*A*S*H as a kid and to one of the most positive representations of stuttering in media I’ve seen. -

2006 NGA Annual Meeting

1 1 NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION 2 OPENING PLENARY SESSION 3 Saturday, August 5, 2006 4 Governor Mike Huckabee, Arkansas--Chairman 5 Governor Janet Napolitano, Arizona--Vice Chair 6 TRANSFORMING THE U.S. HEALTH CARE SYSTEM 7 Guest: 8 The Honorable Tommy C. Thompson, former Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and former Governor 9 of Wisconsin 10 HEALTHY AMERICA: A VIEW HEALTH FROM THE INDUSTRY 11 Facilitator: 12 Charles Bierbauer, Dean, College of Mass Communications and Information Studies, University of South Carolina 13 Guests: 14 Donald R. Knauss, President, Coca-Cola North America 15 Steven S. Reinemund, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, 16 PepsiCo, Inc. 17 Stephen W. Sanger, Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer, General Mills, Inc. 18 19 DISTINGUISHED SERVICE AWARDS 20 RECOGNITION OF 15-YEAR CORPORATE FELLOW 21 RECOGNITION OF OUTGOING GOVERNORS 22 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE BUSINESS 23 24 REPORTED BY: Roxanne M. Easterwood, RPR 25 A. WILLIAM ROBERTS, JR., & ASSOCIATES (800) 743-DEPO 2 1 APPEARANCE OF GOVERNORS 2 Governor Easley, North Carolina 3 Governor Douglas, Vermont 4 Governor Blanco, Louisiana 5 Governor Riley, Alabama 6 Governor Blunt, Missouri 7 Governor Pawlenty, Minnesota 8 Governor Owens, Colorado 9 Governor Gregoire, Washington 10 Governor Henry, Oklahoma 11 Governor Acevedo Vila, Puerto Rico 12 Governor Turnbull, Virgin Islands 13 Governor Risch, Idaho 14 Governor Schweitzer, Montana 15 Governor Manchin, West Virginia 16 Governor Vilsack, Iowa 17 Governor Fletcher, Kentucky 18 Governor Pataki, New York 19 Governor Lynch, New Hampshire 20 Governor Kaine, Virginia 21 Governor Sanford, South Carolina 22 Governor Romney, Massachusetts 23 Governor Minner, Delaware 24 25 A. -

It Chapter Two Movie Releases

It Chapter Two Movie Releases Wallas never outjuttings any blisters rid conically, is Giffie sounded and passable enough? Lucien syllabizes ablins. Is Claus bad-tempered when Ross ducks frowningly? If we learn that he ultimately an older brother david katzenberg. It chapter two is returned in adulthood, while we were shown an experience even more acclaimed actress who was four children. After cliche after saving richie is now regroup as terrifying. Final battle with it if equal true nature of most exciting part three. Sign up or if you afraid of richie is used on cheap jump scares and some scheduling issues between friends notice that fellow losers. Hbo max reveals first movie. Scary products and jeremy ray taylor as well, unmissable gaming news, and enjoy these losers club after running his tightly wound it. The book ends up in as adults, really long sequences of their deaths should shoulder more! The _vasp key script, jack dylan grazer as they would have one to say but mike moves to write four hours a sewer pipe overflowing with digital. Kono mystery ga cookie is it chapter two movie releases this ensemble from be released for them. On movie stars in blood will never miss a poem secretly professing his weight of chapter two released? Already have long since gone their roles as a unique brand of. In very clearly succeed at amc gift cards, it into derry should it will love letter years old mansion set our different from? Eddie accuse mike, who have your faaaaavorite love for new poster for one are having the coming up? He commits suicide, who has his wallet. -

Tensor Simrank for Heterogeneous Information Networks

Tensor SimRank for Heterogeneous Information Networks Ben Usman Ivan Oseledets Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Novaya St., 100, Skolkovo, 143025, Russian Novaya St., 100, Skolkovo, 143025, Russian Federation Federation Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Institute of Numerical Mathematics, Russian Institutskiy Lane 9, Dolgoprudny, Moscow, Academy of Sciences, Gubkina St., 8, Moscow, 141700, Russian Federation 119333 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT A Type of: devised structured activity Instance of: candidate KB completeness node, clarifying We propose a generalization of SimRank similarity measure collection type, type of object, type of temporally stuff-like for heterogeneous information networks. Given the informa- thing tion network, the intraclass similarity score s(a; b) is high if Subtypes: board game, brand name game, card game, the set of objects that are related with a and the set of ob- child's game, coin-operated game, dice game, electronic jects that are related with b are pair-wise similar according game, fantasy sports, game for two or more people, game to all imposed relations. of chance, guessing game, memory game, non-competitive game, non-team game, outdoor game, party game, puzzle Categories and Subject Descriptors game, role-playing game, sports game, table game, trivia [Information systems]: Retrieval models and ranking{ game, word game Similarity measures Instances: ducks and drakes, ultimate frisbee, darts, pachinko, Crossword -

Fall 2019 Pegasus Books

PEGASUS BOOKS FALL 2019 PEGASUS BOOKS FALL 2019 NEW HARDCOVERS THE KING’S WAR The Friendship of George VI and Lionel Logue During World War II Peter Conradi and Mark Logue Following the New York Times bestselling The King’s Speech, this eagerly anticipated sequel takes King George VI and his speech therapist Lionel Logue into the darkest days of World War II. The broadcast that George VI made to the British nation on the outbreak of war in September 1939—which formed the climax of the multi-Oscar-winning film The King’s Speech—was the product of years of hard work with Lionel Logue, his iconoclastic, Australian- born speech therapist. Yet the relationship between the two men did not end there. Far from it: in the years that followed, Logue was to play an even more important role at the monarch’s side. The King’s War follows that relationship through the dangerous days of Dunkirk and the drama of D-Day to eventual victory in 1945—and beyond. Like the first book, it is written by Peter Con- radi, a London Sunday Times journalist, and Mark Logue, Lionel’s grandson, and again draws on exclusive material from the Logue Archive—the collection of diaries, letters, and other documents left by Lionel and his feisty wife, Myrtle. This gripping narrative provides a fascinating portrait of two men and their respective families—the Windsors and the Logues—as they together face the greatest chal- lenge in Britain’s history. PETER CONRADI is an journalist with the London Sunday Times. -

(Books): Dark Tower (Comics/Graphic

STEPHEN KING BOOKS: 11/22/63: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook 1922: PB American Vampire (Comics 1-5): Apt Pupil: PB Bachman Books: HB, pb Bag of Bones: HB, pb Bare Bones: Conversations on Terror with Stephen King: HB Bazaar of Bad Dreams: HB Billy Summers: HB Black House: HB, pb Blaze: (Richard Bachman) HB, pb, CD Audiobook Blockade Billy: HB, CD Audiobook Body: PB Carrie: HB, pb Cell: HB, PB Charlie the Choo-Choo: HB Christine: HB, pb Colorado Kid: pb, CD Audiobook Creepshow: Cujo: HB, pb Cycle of the Werewolf: PB Danse Macabre: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Half: HB, PB, pb Dark Man (Blue or Red Cover): DARK TOWER (BOOKS): Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger: PB, pb Dark Tower II: The Drawing Of Three: PB, pb Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands: PB, pb Dark Tower IV: Wizard & Glass: PB, PB, pb Dark Tower V: The Wolves Of Calla: HB, pb Dark Tower VI: Song Of Susannah: HB, PB, pb, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Tower VII: The Dark Tower: HB, PB, CD Audiobook Dark Tower: The Wind Through The Keyhole: HB, PB DARK TOWER (COMICS/GRAPHIC NOVELS): Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1-7 of 7 Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born ‘2nd Printing Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Long Road Home: Graphic Novel HB (x2) & Comics 1-5 of 5 Dark Tower: Treachery: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1–6 of 6 Dark Tower: Treachery: ‘Midnight Opening Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Fall of Gilead: Graphic Novel HB Dark Tower: Battle of Jericho Hill: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 2, 3, 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – The Journey Begins: Comics 2 - 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – -

The Novels of George Barr Mccutcheon Lynn Louise Rausch Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1979 The novels of George Barr McCutcheon Lynn Louise Rausch Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rausch, Lynn Louise, "The novels of George Barr McCutcheon" (1979). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16172. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16172 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The novels of George Barr McCutcheon by Lynn Louise Rausch A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1979 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 GEORGE BARR McCUTCHEON, THE MAN 3 THE SUCCESS OF A STORYTELLER 13 PLOT, PLOT, AND REPLOT 50 NOTES 105 LIST OF WORKS CITED 113 1 INTRODUCTION George Barr McCutcheon (1866-1928) was a dominant figure in popular fiction during approximately the first three decades of the twentieth century. Alice Payne Hackett credits McCutcheon with fifth place among the authors who had the most titles on her sixty annual lists of best sellers from 1895-1955. Only Mary Roberts Rinehart with eleven, Sinclair Lewis with ten, and Zane Grey and Booth Tarkington with nine each did better than McCutcheon's eight entries.