Letters from the Right: Content-Analysis of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| True Believer 1St Edition

TRUE BELIEVER 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Nicholas Sparks | 9781455571666 | | | | | The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements Early in the book Hoffer identifies many true believers as those who seek "substitutes either for the whole self or for the elements which make life bearable and which they cannot evoke out of their individual resources. This is silly and simplistic. While all these studies are equally indispensable in the studying of mass movements, it's the contemporary associations that Hoffer didn't get to see which really quantifies the power of this book. The playing field is emotion, not reason, and the True Believer 1st edition of the movement ultimately depends on its ability to foster cohesion, unity, the sense of being part of a tribe. All mass movements are uncompromising. It's about how True Believer 1st edition seas of people congeal to hate or be fascinated by True Believer 1st edition certain object, person, ideology. It is essential to have a tangible enemy, not merely an abstract one. Related Articles. Apr 14, Olivia rated it it was ok. The "practical men of action" take over leadership from the fanatics, marking the end of the "dynamic phase" and steering the mass movement away from the fanatic's self-destructiveness. This book had an interesting plot and vulnerable characters. Online Collections. Cover of the first edition. True Believer 1st edition 1 comment. A born skeptic, he travels to the small town of Boone Creek, North Carolina, determined to find t From the world's most beloved chronicler of the heart comes this astonishing story of everlasting love. -

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

The Public Eye, Fall 2002

TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL PublicEyeRESEARCH ASSOCIATES FALL 2002 • Volume XVI, No. 3 The Right Family Values The Christian Right’s “Defense of Marriage:” unpopular beliefs. Despite the First Amendment’s prohi- Democratic Rhetoric, Antidemocratic Politics bition against the establishment of religion by government, Christian conservatives By R. Claire Snyder cans oppose. While conservative Americans and their supporters often insist that Amer- are free to practice their beliefs and live their ica is really a “Christian nation.” They Introduction1 personal lives however they choose, the argue that the American founders believed government of the United States cannot he United States was founded as a that democratic political institutions would legitimately let those beliefs violate the “liberal democracy,” in which a secu- only work if grounded in religious mores T human rights of others in society. Similarly, lar government acts to protect the civil within civil society, emphasizing a comment it cannot generate public policy supporting rights and liberties of individuals rather made by John Adams: “Our Constitution a particular religious worldview or deny legal than imposing a particular vision of the was made only for a moral and religious peo- equality to certain groups of citizens. “good life” on its citizens. Equality before ple. It is wholly inadequate to the govern- the law constitutes one of the most funda- ment of any other.”9 William Bennett has mental principles of liberal democracy, as Liberal Democracy or Christian Nation? contributed greatly to this right-wing proj- does freedom from State-imposed religion. ect of revisionist historiography with the iberal political theory constitutes the These principles, enshrined in our found- publication of Our Sacred Honor: Words of ing documents, have become an almost Lmost important founding tradition of 5 Advice from the Founders, a volume that cat- universally accepted norm in U.S. -

A VOICE from the DEAD Philosophical Arabesques

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service A VOICE FROM THE DEAD Helena Sheehan Introduction to Philosophical Arabesques by Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (1888-1938) published by Monthly Review Press and New York University Press New York 2004 This is a voice from the dead. It is a voice speaking to a time that never heard it, a time that never had a chance to hear it. It is only speaking now to a time not very well disposed to hearing it. This text was written in 1937 in the dark of the night in the depths of the Lubyanka prison in Moscow. It was completed in November on the 20 th anniversary of the socialist revolution to which its author had given his life, the revolution that was in the process of devouring its own true believers, the revolution that was not only condemning him to death but demanding that he slander his whole life. This text lay buried in a Kremlin vault for more than half a century after its author had been executed and his name expunged from the pages of the books telling of the history he had participated in making. After decades, his name was restored and his memory honoured in a brief interval where the story of the revolution was retold, retold in a society to which it crucially mattered, just before that society collapsed to be replaced by one in which the story was retold in another and hostile way, a society in which his legacy no longer mattered to many. -

Indirect Personality Assessment of the Violent True Believer

JOURNAL OF PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT, 82(2), 138–146 Copyright © 2004, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. MASTER LECTURE Indirect Personality Assessment of the ViolentPERSONALITY ASSESSMENTMELOY OF THE VIOLENTTrue TRUE BELIEVER Believer J. Reid Meloy Department of Psychiatry University of California, San Diego and University of San Diego School of Law The violent true believer is an individual committed to an ideology or belief system which ad- vances homicide and suicide as a legitimate means to further a particular goal. The author ex- plores useful sources of evidence for an indirect personality assessment of such individuals. He illustrates both idiographic and nomothetic approaches to indirect personality assessment through comparative analyses of Timothy McVeigh, an American who bombed the federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995, and Mohamed Atta, an Egyptian who led the airplane at- tacks against the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001. The risks of indirect personal- ity assessment and ethical concerns are identified. For the past 9 years I have been intermittently consulting Immediately following the September 11 attacks and in with various federal intelligence agencies, teaching them the midst of my own shock and grief, I decided that the best what we know about such things as psychopathy and helping contribution I could make would be to help the intelligence them to understand the motivations and behaviors of various community understand an individual who develops a homi- individuals who threaten our national security. Following cidal and suicidal state of mind. I marshaled my resources, September 11, 2001, the frequency and intensity of this work contacted several colleagues, and within 10 days we pro- increased dramatically, and out of the awful flowering of the duced an advisory paper that was submitted to the Behavioral terrorist attacks on that autumn day blossomed a construct, Analysis Program of the Counterintelligence Division of the “the violent true believer,” about which I want to speak. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

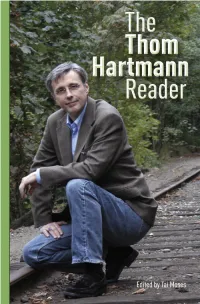

The Thom Hartmann Reader

An Excerpt From The Thom Hartmann Reader by Thom Hartmann Edited by Tai Moses Published by Berrett-Koehler Publishers The Thom Hartmann Reader Thom Hartmann Edited by Tai Moses Contents Editor’s Note ix Introduction: The Stories of Our Times 1 Part I We the People 7 The Radical Middle 10 The Story of Carl 13 Democracy Is Inevitable 31 An Informed and Educated Electorate 39 Whatever Happened to Cannery Row? 53 Part II Brainstorms 57 The Edison Gene 60 Older and Younger Cultures 78 Framing 88 Walking the Blues Away 103 Part III Visions and Visionaries 115 Life in a Tipi 118 How to Raise a Fully Human Child 122 Starting Salem in New Hampshire 137 Younger-Culture Drugs of Control 145 The Secret of “Enough” 158 viii The Thom Hartmann Reader Part IV Earth and Edges 165 The Atmosphere 167 The Death of the Trees 176 Cool Our Fever 183 Something Will Save Us 198 Part V Journeys 209 Uganda Sojourn 211 Russia: A New Seed Planted among Thorns 221 Caral, Peru: A Thousand Years of Peace 235 After the Crash 251 Part VI America the Corporatocracy 263 The True Story of the Boston Tea Party 266 Wal-Mart Is Not a Person 274 Medicine for Health, Not for Profi t 293 Privatizing the Commons 302 Sociopathic Paychecks 312 Acknowledgments 317 Notes 319 Index 329 About the Author 341 About the Editor 343 PART I We the People t’s hard to pigeonhole Thom Hartmann. He has a unique I synthesis of qualities not oft en found in one person: a scholar’s love of history, a scientist’s zeal for facts, a visionary’s seeking aft er truth, an explorer’s appetite for adventure and novelty. -

The Long New Right and the World It Made Daniel Schlozman Johns

The Long New Right and the World It Made Daniel Schlozman Johns Hopkins University [email protected] Sam Rosenfeld Colgate University [email protected] Version of January 2019. Paper prepared for the American Political Science Association meetings. Boston, Massachusetts, August 31, 2018. We thank Dimitrios Halikias, Katy Li, and Noah Nardone for research assistance. Richard Richards, chairman of the Republican National Committee, sat, alone, at a table near the podium. It was a testy breakfast at the Capitol Hill Club on May 19, 1981. Avoiding Richards were a who’s who from the independent groups of the emergent New Right: Terry Dolan of the National Conservative Political Action Committee, Paul Weyrich of the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress, the direct-mail impresario Richard Viguerie, Phyllis Schlafly of Eagle Forum and STOP ERA, Reed Larson of the National Right to Work Committee, Ed McAteer of Religious Roundtable, Tom Ellis of Jesse Helms’s Congressional Club, and the billionaire oilman and John Birch Society member Bunker Hunt. Richards, a conservative but tradition-minded political operative from Utah, had complained about the independent groups making mischieF where they were not wanted and usurping the traditional roles of the political party. They were, he told the New Rightists, like “loose cannonballs on the deck of a ship.” Nonsense, responded John Lofton, editor of the Viguerie-owned Conservative Digest. If he attacked those fighting hardest for Ronald Reagan and his tax cuts, it was Richards himself who was the loose cannonball.1 The episode itself soon blew over; no formal party leader would follow in Richards’s footsteps in taking independent groups to task. -

Totalitarianism 1 Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism 1 Totalitarianism Totalitarianism (or totalitarian rule) is a political system where the state holds total authority over the society and seeks to control all aspects of public and private life wherever necessary.[1] The concept of totalitarianism was first developed in a positive sense in the 1920's by the Italian fascists. The concept became prominent in Western anti-communist political discourse during the Cold War era in order to highlight perceived similarities between Nazi Germany and other fascist regimes on the one hand, and Soviet communism on the other.[2][3][4][5][6] Aside from fascist and Stalinist movements, there have been other movements that are totalitarian. The leader of the historic Spanish reactionary conservative movement called the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right declared his intention to "give Spain a true unity, a new spirit, a totalitarian polity..." and went on to say "Democracy is not an end but a means to the conquest of the new state. Moloch of Totalitarianism – memorial of victims of repressions exercised by totalitarian regimes, When the time comes, either parliament submits or we will eliminate at Levashovo, Saint Petersburg. it."[7] Etymology The notion of "totalitarianism" a "total" political power by state was formulated in 1923 by Giovanni Amendola who described Italian Fascism as a system fundamentally different from conventional dictatorships.[8] The term was later assigned a positive meaning in the writings of Giovanni Gentile, Italy’s most prominent philosopher and leading theorist of fascism. He used the term “totalitario” to refer to the structure and goals of the new state. -

Trump's All Too Familiar Strategy and Its Future in The

The Forum 2016; 14(3): 295–309 Zoltan Hajnal* and Marisa Abrajano* Trump’s All Too Familiar Strategy and Its Future in the GOP DOI 10.1515/for-2016-0023 Abstract: Although many observers have been surprised both by the racial explicit nature of Donald Trump’s campaign and the subsequent success of that cam- paign, we contend that Trump’s tactics and their success are far from new. We describe how for the past half century Republicans have used race and increas- ingly immigration to attract white voters – especially working class whites. All of this has led to an increasingly racially polarized polity and for the most part Republican electoral success. We conclude with some expectations about the future of race, immigration, and party politics. Introduction Donald Trump attacks Mexican immigrants. He disparages Muslims. He insults women. And what happens? Voters flock to him. Trump’s rapid rise to the top of the Republican polls and his enduring role as the Party’s nominee sparked all kinds of diverse reactions. The Republican establishment was scared. The Demo- cratic Party was appalled. And the media was enthralled. But the most common reaction of all was surprise. Many wondered how Trump could end up as the Republican nominee? How could a campaign prem- ised on prejudice and denigration be so successful? Trump may ultimately lose his presidential bid but not before capturing the Republican Party and the hearts of millions of Americans. How could it happen? Why did it happen? Even though many seemed surprised by the rise of Donald Trump, nobody should be. -

The Rearguard of Freedom: the John Birch Society and the Development

The Rearguard of Freedom: The John Birch Society and the Development of Modern Conservatism in the United States, 1958-1968 by Bart Verhoeven, MA (English, American Studies), BA (English and Italian Languages) Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Arts July 2015 Abstract This thesis aims to investigate the role of the anti-communist John Birch Society within the greater American conservative field. More specifically, it focuses on the period from the Society's inception in 1958 to the beginning of its relative decline in significance, which can be situated after the first election of Richard M. Nixon as president in 1968. The main focus of the thesis lies on challenging more traditional classifications of the JBS as an extremist outcast divorced from the American political mainstream, and argues that through their innovative organizational methods, national presence, and capacity to link up a variety of domestic and international affairs to an overarching conspiratorial narrative, the Birchers were able to tap into a new and powerful force of largely white suburban conservatives and contribute significantly to the growth and development of the post-war New Right. For this purpose, the research interrogates the established scholarship and draws upon key primary source material, including official publications, internal communications and the private correspondence of founder and chairman Robert Welch as well as other prominent members. Acknowledgments The process of writing a PhD dissertation seems none too dissimilar from a loving marriage. It is a continuous and emotionally taxing struggle that leaves the individual's ego in constant peril, subjugates mind and soul to an incessant interplay between intense passion and grinding routine, and in most cases should not drag on for over four years. -

The Peaceful Xenophobes by Eric Kaufmann

Issue 152, November 2008 The peaceful xenophobes by Eric Kaufmann Two new studies of empire and nationalism should make us think again about conflating xenophobia, nationalism and aggression Eric Kaufmann is a fellow at the Belfer Centre, Harvard University For Kin or Country: Xenophobia, Nationalism and War by Stephen Saideman and William Ayres (Columbia University Press, £20.95) Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance--and Why They Fall by Amy Chua (Doubleday, £16.95) Intolerance towards minorities and belligerence towards other nations are usually regarded as two sides of the same coin. Yet this Nazi-centric interpretation does serious injury to a historical record in which tolerance has often proved the handmaiden of "missionary" imperialism, while xenophobia has constrained expansionist energies. Now, at a time when politicians and academics like to stress the importance of outward-looking, tolerant, "civic" nationhood, it is a distinction eminently worth chewing over. In many big modern states, like Britain and America, the downplaying of majority ethnic identity has allowed internal "others" to be included, but has also placed more pressure on political elites to define national identity against external "others." In other words, rather than basing national identity on the particularity of who we are, the game becomes one of evangelising our identity to the world. Other countries, of course, may not be interested in such evangelism, in which case a coercive approach to spreading this identity--be it liberalism, socialism, Christianity or Islam--becomes necessary, increasing the potential for international conflict. Iran, Britain and the US are archetypal "missionary nationalists" of this type, while Estonia, Poland or Wales fall into the opposite ethnonational category.