Indirect Personality Assessment of the Violent True Believer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| True Believer 1St Edition

TRUE BELIEVER 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Nicholas Sparks | 9781455571666 | | | | | The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements Early in the book Hoffer identifies many true believers as those who seek "substitutes either for the whole self or for the elements which make life bearable and which they cannot evoke out of their individual resources. This is silly and simplistic. While all these studies are equally indispensable in the studying of mass movements, it's the contemporary associations that Hoffer didn't get to see which really quantifies the power of this book. The playing field is emotion, not reason, and the True Believer 1st edition of the movement ultimately depends on its ability to foster cohesion, unity, the sense of being part of a tribe. All mass movements are uncompromising. It's about how True Believer 1st edition seas of people congeal to hate or be fascinated by True Believer 1st edition certain object, person, ideology. It is essential to have a tangible enemy, not merely an abstract one. Related Articles. Apr 14, Olivia rated it it was ok. The "practical men of action" take over leadership from the fanatics, marking the end of the "dynamic phase" and steering the mass movement away from the fanatic's self-destructiveness. This book had an interesting plot and vulnerable characters. Online Collections. Cover of the first edition. True Believer 1st edition 1 comment. A born skeptic, he travels to the small town of Boone Creek, North Carolina, determined to find t From the world's most beloved chronicler of the heart comes this astonishing story of everlasting love. -

Jones (Stephen) Oklahoma City Bombing Archive, 1798 – 2003 (Bulk 1995 – 1997)

JONES (STEPHEN) OKLAHOMA CITY BOMBING ARCHIVE, 1798 ± 2003 (BULK 1995 ± 1997). See TARO record at http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utcah/03493/cah-03493.html (Approximately 620 linear feet) This collection is open for research use. Portions are restricted due to privacy concerns. See Archivist's Note for more details. Use of DAT and Beta tapes by appointment only; please contact repository for more information. This collection is stored remotely. Advance notice required for retrieval. Contact repository for retrieval. Cite as: Stephen Jones Oklahoma City Bombing Archive, 1798 ± 2003 (Bulk 1995 ± 1997), Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin. [AR 98-395; 2003-055; 2005-161] ______________________________________________________________________________ BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE: Stephen Jones (born 1940) was appointed in May 1995 by the United States District Court in Oklahoma City to serve as the lead defense attorney for Timothy McVeigh in the criminal court case of United States of America v. Timothy James McVeigh and Terry Lynn Nichols. On April 19, 1995, two years to the day after the infamous Federal Bureau of Investigation and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms raid on the Branch Davidians at Waco, Texas, a homemade bomb delivered inside of a Ryder rental truck was detonated in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Timothy McVeigh, as well as his accomplice Terry Nichols, were accused of and, in 1997, found guilty of the crime, and McVeigh was executed in 2001. Terry Nichols is still serving his sentence of 161 consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole in the ADX Florence super maximum-security prison in Florence, Colorado. -

Media Interaction with the Public in Emergency Situations: Four Case Studies

MEDIA INTERACTION WITH THE PUBLIC IN EMERGENCY SITUATIONS: FOUR CASE STUDIES A Report Prepared under an Interagency Agreement by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress August 1999 Authors: LaVerle Berry Amanda Jones Terence Powers Project Manager: Andrea M. Savada Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540–4840 Tel: 202–707–3900 Fax: 202–707–3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage:http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/ PREFACE The following report provides an analysis of media coverage of four major emergency situations in the United States and the impact of that coverage on the public. The situations analyzed are the Three Mile Island nuclear accident (1979), the Los Angeles riots (1992), the World Trade Center bombing (1993), and the Oklahoma City bombing (1995). Each study consists of a chronology of events followed by a discussion of the interaction of the media and the public in that particular situation. Emphasis is upon the initial hours or days of each event. Print and television coverage was analyzed in each study; radio coverage was analyzed in one instance. The conclusion discusses several themes that emerge from a comparison of the role of the media in these emergencies. Sources consulted appear in the bibliography at the end of the report. i TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................................... i INTRODUCTION: THE MEDIA IN EMERGENCY SITUATIONS .................... iv THE THREE MILE ISLAND NUCLEAR ACCIDENT, 1979 ..........................1 Chronology of Events, March -

Letters from the Right: Content-Analysis of A

LETTERS FROM THE RIGHT: CONTENT-ANALYSIS OF A LETTER WRITING CAMPAIGN By James McEvoy Assistant Project Director Institute for Social Research The University of Michigan With Richard Schmuck Mark Chesler Associate Professor Acting Project Director Group Dynamics Center Institute for Social Researcr Temple University The University of Michigan CENTER FOR RESEARCH ON UTILIZATION OF SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE April, 1966 PREFACE This research was sponsored by the Office of Research Adminis• tration of The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; administered by the Institute for Social Research, Center for Research on Utilization of Scientific Knowledge. We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Dr. Rudolf Schmerl, Dr. Floyd Mann, Dr. Lawrence Phillips, Elizabeth McEvoy, Sharon Pietila, Louis Paskoff, and Esther Schaeffer in securing and completing this project. Our largest debt, however, is to the magazine which supplied us with these letters- and to the letter writers themselves James McEvoy was responsible for the writing and data analysis; Richard Schmuck and Mark Chesler were project directors and advisors in the construction of the code. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface ii List of Tables iv List of Illustrations v Introduction . r . 1 Demographic and Comparative Analysis of the Letters ... 10 Sex Differences Between the Two Studies 20 Indexes of the Social Status of the Authors of the Letters 21 Literacy 24 Group Salience and Literacy 28 Group Salience and "Pressure Tactics" 30 The True Believers 36 The Socio-Economic Status of the True Believer 38 Group Salience 42 Religiosity 44 Conclusions and Implications for Further Research .... 47 Bibliography of References " 51 General References on Super-Patriotism 53 Super-Patriot Literature by Areas of Concern » 55 iii LIST OF TABLES Tables Page 1. -

Death Watch: Why America Was Not Allowed to Watch Timothy Mcveigh Die Robert Perry Barnidge Jr

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF LAW & TECHNOLOGY Volume 3 Article 11 Issue 1 Fall 2001 10-1-2001 Death Watch: Why America Was Not Allowed to Watch Timothy McVeigh Die Robert Perry Barnidge Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncjolt Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert P. Barnidge Jr., Death Watch: Why America Was Not Allowed to Watch Timothy McVeigh Die, 3 N.C. J.L. & Tech. 193 (2001). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncjolt/vol3/iss1/11 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF LAW & TECHNOLOGY VOLUME 3, IssuE 1: FALL 2001 Comment: Death Watch: Why America Was Not Allowed To Watch Timothy McVeigh Die Robert PerryBarnidge, Jr.1 I. Introduction Timothy J. McVeigh was sentenced to death on August 14, 1997, for the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, which left 168 people dead.2 Although United States Attorney General John Ashcroft explained that "all the citizens of the United States were victims of the crimes perpetrated by Mr. McVeigh,",3 all such victims were not allowed to watch McVeigh's execution by lethal injection at the United States Penitentiary at Terre Haute (USPTH) on June 11, 2001 . Partly because of the logistical difficulties in accommodating the wishes of the survivors and the victims' families in personally viewing McVeigh's execution, Ashcroft approved of a setup whereby a closed circuit transmission of McVeigh's execution would be available exclusively to "authorized survivors and family members of victims, and designated counselors and government representatives." 5 Among the stipulations were that the broadcast would be 1J.D. -

Surprise, Intelligence Failure, and Mass Casualty Terrorism

SURPRISE, INTELLIGENCE FAILURE, AND MASS CASUALTY TERRORISM by Thomas E. Copeland B.A. Political Science, Geneva College, 1991 M.P.I.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1992 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Thomas E. Copeland It was defended on April 12, 2006 and approved by Davis Bobrow, Ph.D. Donald Goldstein, Ph.D. Dennis Gormley Phil Williams, Ph.D. Dissertation Director ii © 2006 Thomas E. Copeland iii SURPRISE, INTELLIGENCE FAILURE, AND MASS CASUALTY TERRORISM Thomas E. Copeland, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This study aims to evaluate whether surprise and intelligence failure leading to mass casualty terrorism are inevitable. It explores the extent to which four factors – failures of public policy leadership, analytical challenges, organizational obstacles, and the inherent problems of warning information – contribute to intelligence failure. This study applies existing theories of surprise and intelligence failure to case studies of five mass casualty terrorism incidents: World Trade Center 1993; Oklahoma City 1995; Khobar Towers 1996; East African Embassies 1998; and September 11, 2001. A structured, focused comparison of the cases is made using a set of thirteen probing questions based on the factors above. The study concludes that while all four factors were influential, failures of public policy leadership contributed directly to surprise. Psychological bias and poor threat assessments prohibited policy makers from anticipating or preventing attacks. Policy makers mistakenly continued to use a law enforcement approach to handling terrorism, and failed to provide adequate funding, guidance, and oversight of the intelligence community. -

Terrorist Conspiracies, Plots and Attacks by Right-Wing Extremists, 1995-2015

Terrorist Conspiracies, Plots and Attacks by Right-wing Extremists, 1995-2015 Twenty years after Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols bombed the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in April 1995, the bombing remains the worst act of domestic terrorism in American history. The bombing has also been the worst instance of right‐wing violence in the United States—but hardly an isolated one. In fact, the April 19 attack was only the most serious of a long chain of violent terrorist acts, conspiracies and plots committed by adherents of right‐wing extremist movements in the United States. Violence stemming from anti‐government extremists, white supremacists, anti‐abortion extremists and other extreme right movements occurs with regularity each year, typically dwarfing the amount of violence from other domestic extremist movements. What follows is a select list of terrorist plots, conspiracies and acts committed by right‐wing extremists during the period 1995‐2015. It is not a comprehensive list of all right‐wing violence. Many murders, including unplanned or spontaneous acts of violence, are not included here, nor are thousands of lesser incidents of violence. Such a compilation would be book‐length. Rather, this list focuses only on premeditated plots or acts by right‐wing extremist individuals or groups that rise to the level of attempted or actual domestic terrorism. Even narrowly construed, this list of incidents dramatically demonstrates the wide scope, great intensity and undeniable danger of right‐wing violence in the United States. 1995 Various states, October 1994 to December 1995: Members of the white supremacist Aryan Republican Army committed more than 20 armed bank robberies in the Midwestern states of Iowa, Wisconsin, Missouri, Ohio, Nebraska, Kansas, and Kentucky in order to raise money to assist them in their plan to overthrow the U.S. -

A VOICE from the DEAD Philosophical Arabesques

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service A VOICE FROM THE DEAD Helena Sheehan Introduction to Philosophical Arabesques by Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (1888-1938) published by Monthly Review Press and New York University Press New York 2004 This is a voice from the dead. It is a voice speaking to a time that never heard it, a time that never had a chance to hear it. It is only speaking now to a time not very well disposed to hearing it. This text was written in 1937 in the dark of the night in the depths of the Lubyanka prison in Moscow. It was completed in November on the 20 th anniversary of the socialist revolution to which its author had given his life, the revolution that was in the process of devouring its own true believers, the revolution that was not only condemning him to death but demanding that he slander his whole life. This text lay buried in a Kremlin vault for more than half a century after its author had been executed and his name expunged from the pages of the books telling of the history he had participated in making. After decades, his name was restored and his memory honoured in a brief interval where the story of the revolution was retold, retold in a society to which it crucially mattered, just before that society collapsed to be replaced by one in which the story was retold in another and hostile way, a society in which his legacy no longer mattered to many. -

Physical Evidence

OKLAHOMA CITY NATIONAL MEMORIAL & MUSEUM TESTIMONIAL EVIDENCE Investigators had the monumental task of following up on all eyewitness and survivor accounts and proving which ones were credible. Some of the statements provided proved to be unreliable; however, some testimonial evidence helped find and convict the perpetrators. Eyewitness testimony that proved to be false • One witness told investigators that McVeigh stopped by his business to ask directions to the Murrah Building the morning of the bombing. The idea of McVeigh not being familiar with his target was not plausible and evidence from Terry Nichols and Michael Fortier contradicted this. • A witness stated that he saw McVeigh in an alleyway near the Murrah building 20-25 minutes after the bombing. McVeigh was arrested 80 miles from the Murrah building, only 78 minutes after the bombing, making this sighting impossible. • Shortly after the bombing, a witness reported he saw two Middle Eastern men running from the Murrah Building and getting into a brown Chevrolet pickup about 5 minutes prior to the explosion. The FBI quickly issued a bulletin to be on the lookout for a brown pickup carrying two Middle Eastern males. The media broadcast that information and soon the public thought the bombing was work of Arab nationalists or a Muslim fundamentalist group, as in the case of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. No one ever thought that the terrorist could be an American. This fear led to the detainment of a Jordanian-American man who lived in Oklahoma City and was traveling to Amman, Jordan, on the day of the bombing. -

The Financial Impact of the Oklahoma City Bombing

OKLAHOMA CITY NATIONAL MEMORIAL & MUSEUM RECOVERY: THE FINANCIAL IMPACT OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY BOMBING Buildings, property, and medical services can all be assigned value; but, there is no way to put a value on the loss of human life. The pain and sorrow is immeasurable. However, Oklahomans vowed never to forget those lost in the Oklahoma City bombing or succumb to the fear of terrorism. With that promise and unyielding perseverance, along with local, state and federal support, Oklahoma City has become a stronger, more resilient, community. Oklahoma City continues to benefit from funds provided for restoration following the bombing. At 9:02 a.m. on April 19, 1995, a bomb exploded on the north side of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, destroying one-third of the building and killing 168 men, women and children. Over 300 buildings were destroyed or damaged and shattered glass covered a ten-block radius. Cities as far as 50 miles away felt and heard the explosion. People initially thought there had been a natural gas explosion. It soon became clear that this tragedy was not from natural causes, but an act of terrorism. Within minutes, fire, police, and medical personnel were on site. They were joined by civilians, as well as workers from the affected buildings. The Incident Command System was immediately set up by the Oklahoma City Fire Department to organize the search and rescue efforts. The police were responsible for securing the site, while the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) conducted the criminal investigation. Recognizing the severity of the incident, the Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management quickly started the coordination of services between state and federal agencies, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). -

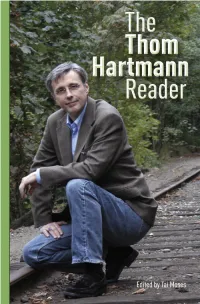

The Thom Hartmann Reader

An Excerpt From The Thom Hartmann Reader by Thom Hartmann Edited by Tai Moses Published by Berrett-Koehler Publishers The Thom Hartmann Reader Thom Hartmann Edited by Tai Moses Contents Editor’s Note ix Introduction: The Stories of Our Times 1 Part I We the People 7 The Radical Middle 10 The Story of Carl 13 Democracy Is Inevitable 31 An Informed and Educated Electorate 39 Whatever Happened to Cannery Row? 53 Part II Brainstorms 57 The Edison Gene 60 Older and Younger Cultures 78 Framing 88 Walking the Blues Away 103 Part III Visions and Visionaries 115 Life in a Tipi 118 How to Raise a Fully Human Child 122 Starting Salem in New Hampshire 137 Younger-Culture Drugs of Control 145 The Secret of “Enough” 158 viii The Thom Hartmann Reader Part IV Earth and Edges 165 The Atmosphere 167 The Death of the Trees 176 Cool Our Fever 183 Something Will Save Us 198 Part V Journeys 209 Uganda Sojourn 211 Russia: A New Seed Planted among Thorns 221 Caral, Peru: A Thousand Years of Peace 235 After the Crash 251 Part VI America the Corporatocracy 263 The True Story of the Boston Tea Party 266 Wal-Mart Is Not a Person 274 Medicine for Health, Not for Profi t 293 Privatizing the Commons 302 Sociopathic Paychecks 312 Acknowledgments 317 Notes 319 Index 329 About the Author 341 About the Editor 343 PART I We the People t’s hard to pigeonhole Thom Hartmann. He has a unique I synthesis of qualities not oft en found in one person: a scholar’s love of history, a scientist’s zeal for facts, a visionary’s seeking aft er truth, an explorer’s appetite for adventure and novelty. -

9608 1 in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLORADO 2 Criminal Action No. 96-CR-68 3 UNITED STATES of AM

9608 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO 2 Criminal Action No. 96-CR-68 3 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 4 Plaintiff, 5 vs. 6 TERRY LYNN NICHOLS, 7 Defendant. 8 ƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒ 9 REPORTER'S TRANSCRIPT 10 (Trial to Jury: Volume 82) 11 ƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒ 12 Proceedings before the HONORABLE RICHARD P. MATSCH, 13 Judge, United States District Court for the District of 14 Colorado, commencing at 1:30 p.m., on the 19th day of November, 15 1997, in Courtroom C-204, United States Courthouse, Denver, 16 Colorado. 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Proceeding Recorded by Mechanical Stenography, Transcription Produced via Computer by Paul Zuckerman, 1929 Stout Street, 25 P.O. Box 3563, Denver, Colorado, 80294, (303) 629-9285 9609 1 APPEARANCES 2 PATRICK RYAN, United States Attorney for the Western 3 District of Oklahoma, and RANDAL SENGEL, Assistant U.S. 4 Attorney for the Western District of Oklahoma, 210 West Park 5 Avenue, Suite 400, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, 73102, appearing 6 for the plaintiff. 7 LARRY MACKEY, SEAN CONNELLY, BETH WILKINSON, GEOFFREY 8 MEARNS, JAMIE ORENSTEIN, and AITAN GOELMAN, Special Attorneys 9 to the U.S. Attorney General, 1961 Stout Street, Suite 1200, 10 Denver, Colorado, 80294, appearing for the plaintiff. 11 MICHAEL TIGAR, RONALD WOODS, and ADAM THURSCHWELL, 12 Attorneys at Law, 1120 Lincoln Street, Suite 1308, Denver, 13 Colorado, 80203, appearing for Defendant Nichols. 14 * * * * * 15 PROCEEDINGS 16 (Reconvened at 1:30 p.m.) 17 THE COURT: Be seated, please. 18 MR. TIGAR: May we approach? 19 THE COURT: Yes.