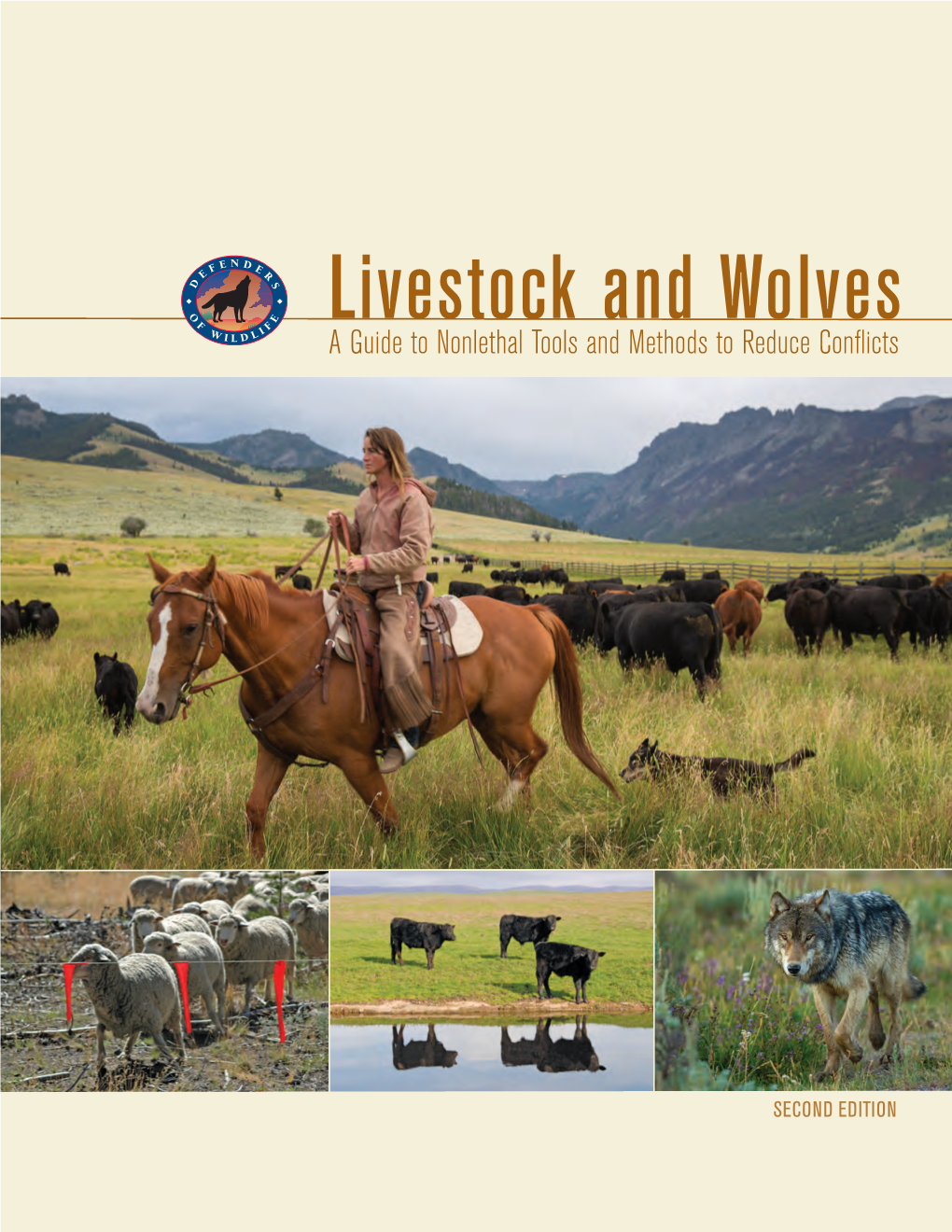

Livestock and Wolves: a Guide to Nonlethal Tools and Methods to Reduce Conflicts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selecting a Livestock Guardian Dog Puppy

University of California Cooperative Extension Livestock Protection Tools Fact Sheets Number 5 Selecting a Livestock Guardian Dog Puppy By Dan Macon, Livestock and Natural Resources Advisor (Placer-Nevada-Sutter-Yuba) and Carolyn Whitesell, Human- Wildlife Interactions Advisor (San Mateo-San Francisco) Adapted from “How to Select an LGD Puppy” by Bill Constanzo, Livestock Guardian Dog Research Specialist, Texas A&M AgriLife Center Overview Puppy selection is often the critical first step towards successfully using livestock guardian dogs (LGDs) in a production setting. While appropriate bonding during the first 12-18 months of a dog’s life is important, pups with an inherent genetic predisposition for guarding livestock are more likely to become successful adult LGDs. Furthermore, physical traits (like hair coat, color, mature size, etc.) are preset by a pup’s genetics. Keep in mind that LGD behaviors are greatly influenced by how they are treated during the first year of their life. This fact sheet will help you select an LGD pup that will most likely fit your particular needs. Buy a Pup from Reputable Genetics: Purchasing a pup from working parents will increase the likelihood of success. A knowledgeable breeder (who may also be a livestock producer) will know the pedigree of his or her pups, as well as the individual behaviors of the parents. While observation over time is generally more reliable than puppy aptitude testing, you should still try to observe the pups, as well as the parents, in their working setting. Were the pups whelped where they could hear and smell livestock before their eyes were open? What kind of production system (e.g., open range, farm flock, extensive pasture system, etc.) do the parents work in? If you cannot observe the pups in person before purchasing, ask the breeder for photos and/or videos, and ask them about the behavioral traits discussed below. -

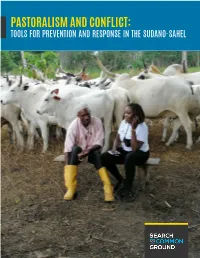

PASTORALISM and CONFLICT: TOOLS for PREVENTION and RESPONSE in the SUDANO-SAHEL Partnership for Stability and Security in the Sudano-Sahel

PASTORALISM AND CONFLICT: TOOLS FOR PREVENTION AND RESPONSE IN THE SUDANO-SAHEL Partnership for Stability and Security in the Sudano-Sahel This report was produced in collaboration with the U.S. State Department, Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO), as part of the project Partnership for Stability and Security in the Sudano-Sahel (P4SS). The goal of this project is to inform stabilization and development efforts in communities across the Sudano-Sahel affected by cross-border farmer-herder conflict by identifying proven, data-informed methods of conflict transformation. AUTHORS Mike Jobbins, Search for Common Ground Andrew McDonnell, Search for Common Ground This report was made possible by the support of the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO). The views expressed in the report are those of the authors alone and do not represent the institutional position of the U.S. Government, or the Search for Common Ground. © 2021 Search for Common Ground This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form without permission from Search for Common Ground, provided the reproduction includes this Copyright notice and the Disclaimer below. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from Search for Common Ground. This publication should be cited as follows: Jobbins, Mike and Andrew McDonnell. (2021). Pastoralism and Conflict: Tools for Prevention and Response in the Sudano- Sahel, 1st ed. Washington DC: Search for Common Ground. Cover photo credit: Alhaji Musa. 2 | Pastoralism and Conflict: Tools for Prevention and Response Methodology and Development The findings and recommendations in this Toolkit were identified based on a meta-review of program evaluations and scholarly research in French and English, supplemented by a series of key informant interviews with program implementers. -

Congratulations on Your New Anatolian!

The ANATOLIAN SHEPHERD DOG — Congratulations on Your New Anatolian! HISTORY First entering the United States in the 1950’s, the Anatolian Shepherd Dog is a livestock guardian breed with its origin in Turkey and Asia Minor. Quite probably over 6,000 years old, the breed is impressive in size, serving Turkish shepherds as front-line defense from predators. DESCRIPTION Large, rugged, powerful and impressive, Anatolians possess great endurance and agility. Developed through a set of very demanding circumstances for a purely utilitarian purpose, he is a working guard dog without equal, with a unique ability to protect livestock. General impression is that he appears bold, but calm, unless challenged. Loyalty, an Anatolian so that his guarding instincts can be exercised independence, intelligence, and hardiness are just some of in a responsible manner. the factors appreciated by fanciers of the breed. HEALTH & FEEDING CARE & HOUSING Given proper care and nourishment, an Anatolian is a Adding a large, protective dog to your life should be an basically healthy dog. Life spans of twelve or more years earnest and thoughtful process, not an impulsive decision. are not uncommon. Feed a well balanced diet not too high Anatolians are guardians by instinct, not by training. in protein with a proper mineral, fat and calorie content. Their basic personality is different from most breeds, since Clean, fresh water should be available at all times. Pups most breeds were bred to take commands from people. and grown dogs love to chew. They have strong jaws and Anatolians, however, were created to make decisions on you must be sure to only give them appropriate items their own with little or no input from people. -

SOUND AGRICULTURAL PRACTICE Opinion Number 20-1

SOUND AGRICULTURAL PRACTICE Opinion Number 20-1 SUBJECT: Request for an Opinion Pursuant to Section 308 of the Agriculture and Markets Law as to the soundness of the use of livestock guardian dogs by Joshua Rockwood of West Wind Acres. REQUESTOR: Joshua Rockwood West Wind Acres 144 Beebe Road Knox, NY 12023 Preliminary Statement On September 19, 2019, Joshua Rockwood, owner of West Wind Acres, requested that the Commissioner issue an Opinion as to the soundness of the use of livestock guardian dogs to protect his pasture raised meat chickens, egg chickens and turkeys from predation. This request arises from complaints from a neighbor about barking, particularly at night. The Department conducted a sound agricultural practice review for the use of livestock guardian dogs on the property leased by Mr. Rockwood for the raising of livestock. For the reasons set forth below, West Wind Acres' use of livestock guardian dogs is a sound agricultural practice. The following information and findings have been considered in reaching this Opinion. Information Considered in Support of the Opinion THE FARM 1. West Wind Acres, founded in 2011, is a pasture-based farm used to raise pigs, grass fed beef cattle, spotted draft horses, chickens and turkeys. In June 2017, West Wind Acres moved from a prior location to its current location in the Town of Knox, consisting of approximately four hundred acres of leased land from Local Farms Fund. Local Farms Fund is a community impact farmland investment fund that supports young and early stage farmers to provide a path to eventual ownership of the farmland by the leasing farmer, typically after a 5-year term. -

The Dog Buyer's Guide

THE DOG BUYER’S GUIDE The Society for Canine Genetic Health and Ethics www.koiranjalostus.fi Foreword The main purpose of the A dog is a living creature We hope you will find this guidebook is to provide and no one can guarantee that guide useful in purchasing help for anyone planning your dog will be healthy and your dog! the purchase of his or her flawless. Still, it pays to choose first dog. However, it can be a breeder who does his best useful for anyone planning to guarantee it. We hope this to get a dog. Our aim is to guide will help you to actively help you and your family to and critically find and process choose a dog that best suits information about the health, your needs and purposes. characteristics and behaviour of the breed or litter of your Several breeds seem to be choice. plagued with health and character problems. The This guide has been created, Finnish Society for Canine written and constructed by Genetic Health and Ethics the members of the HETI (HETI) aims to influence society: Hanna Bragge, Päivi dog breeding by means of Jokinen, Anitta Kainulainen, information education. Our Inkeri Kangasvuo, Susanna aim is to see more puppies Kangasvuo, Tiina Karlström, born to this world free of Pertti Kellomäki, Sara genetic disorders that would Kolehmainen, Saija Lampinen, deteriorate their quality of life Virpi Leinonen, Helena or life-long stress caused by, Leppäkoski, Anna-Elisa for example, defects in the Liinamo, Mirve Liius, Eira nervous system. Malmstén, Erkki Mäkelä, Katariina Mäki, Anna Niiranen, The demand of puppies is Tiina Notko, Riitta Pesonen, one of the most important Meri Pisto koski, Maija factors that guides the dog Päivärinta, Johanna Rissanen, breeding. -

Genomic Characterization of the Three Balkan Livestock Guardian Dogs

sustainability Article Genomic Characterization of the Three Balkan Livestock Guardian Dogs Mateja Janeš 1,2 , Minja Zorc 3 , Maja Ferenˇcakovi´c 1, Ino Curik 1, Peter Dovˇc 3 and Vlatka Cubric-Curik 1,* 1 Department of Animal Science, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (M.J.); [email protected] (M.F.); [email protected] (I.C.) 2 The Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH25 9RG, UK 3 Biotechnical Faculty Department of Animal Science, University of Ljubljana, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (P.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +385-1-239-4008 Abstract: Balkan Livestock Guardian Dogs (LGD) were bred to help protect sheep flocks in sparsely populated, remote mountainous areas in the Balkans. The aim of this study was genomic charac- terization (107,403 autosomal SNPs) of the three LGD breeds from the Balkans (Karst Shepherd, Sharplanina Dog, and Tornjak). Our analyses were performed on 44 dogs representing three Balkan LGD breeds, as well as on 79 publicly available genotypes representing eight other LGD breeds, 70 individuals representing seven popular breeds, and 18 gray wolves. The results of multivariate, phylogenetic, clustering (STRUCTURE), and FST differentiation analyses showed that the three Balkan LGD breeds are genetically distinct populations. While the Sharplanina Dog and Tornjak are closely related to other LGD breeds, the Karst Shepherd is a slightly genetically distinct population with estimated influence from German Shepard (Treemix analysis). Estimated genomic diversity was high with low inbreeding in Sharplanina Dog (Ho = 0.315, He = 0.315, and FROH>2Mb = 0.020) and Citation: Janeš, M.; Zorc, M.; Tornjak (Ho = 0.301, He = 0.301, and FROH>2Mb = 0.033) breeds. -

SOUND AGRICULTURAL PRACTICE Opinion Number 17-2

SOUND AGRICULTURAL PRACTICE Opinion Number 17-2 SUBJECT: Request for an Opinion Pursuant to Section 308 of the Agriculture and Markets Law as to the soundness of the use of livestock guardian dogs by John Lemondes to protect his sheep. REQUESTOR: John Lemondes 3390 Eager Road Jamesville, New York 13078 Preliminary Statement On May 15, 2017 John and Martha Lemondes requested that the Commissioner issue an Opinion as to the soundness of the use of livestock guardian dogs to protect their sheep from predation. This request arises from complaints received from a neighbor about the barking of the livestock guardian dogs, particularly at night. The Department conducted a sound agricultural practice review for the use of livestock guardian dogs on multiple parcels of land, in a contiguous block, owned by John and Martha Lemondes. The following information and findings have been considered in reaching this Opinion. Information Considered in Support of the Opinion THE FARM 1. On May 28,2017, Dr. Robert Somers, Manager of the Farmland Protection Program, visited the John and Martha Lemondes property to examine their use of two Great Pyrenees Mountain livestock guardian dogs to protect the farm's sheep (a flock of 62 breeding ewes and three rams) from predation. The Lemondes also have a family pet, a Mountain Kur, that is used to herd the sheep as well as warn the family of any occurrences outside of their home'. Barking arising from the Mountain Kur, or any related on-farm behavior, is not a source of any complaints from neighboring landowners, and is therefore outside the scope of this opinion. -

Livestock Guardian Animals

Wild dog facts Livestock guardian animals Dogs and donkeys are used to guard sheep, goats automatic, though, and some dogs do not perform and breeding cattle from wild dogs and other well despite careful selection and rearing. predators within Australia and overseas. Livestock guardian animals require careful selection and training and there is often a high initial cost outlay. Livestock guardian animals require appropriate husbandry and health care. Guardian dogs Breeding dogs to guard livestock originated in Europe and Asia, where they have been used for centuries to protect livestock from wolves and bears. In Australia, dogs have been successfully used to guard small herds of goats, sheep, deer, Maremma dog guarding goat herd alpaca and even free-range fowl. Several large sheep properties have successfully used guardian Tips to successfully rear a livestock dogs under extensive conditions. guardian dog Some of the more common breeds are Great Select a suitable breed and reputable breeder. Pyrenees from France, the Komondor from Hungary, the Akbash dog and the Anatolian Rear pups with livestock, individually or with shepherd from Turkey, and the Maremma from Italy. experienced dogs, from the age of eight weeks. All of these are large animals, weighing between 35 While rearing the dogs, maintain contact with and 55 kg. They are usually white or fawn coloured them so you can still approach and handle them with dark muzzles. when necessary. Any bonding between owner and dog should happen with the herd so that the The behaviour of livestock guardian dogs differs dog knows its place is with the herd. -

Livestock Guardian Dogs Tompkins Conservation Wildlife Bulletin Number 2, March 2017

LIVESTOCK GUARDIAN DOGS TOMPKINS CONSERVATION WILDLIFE BULLETIN NUMBER 2, MARCH 2017 Livestock vs. Predators TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to an historical conflict and its mitigation PAGE 01 through the use of livestock guardian dogs Livestock vs. Predators: Introduction to an historical conflict and its mitigation through the use Since humans began domesti- stock and wild predators. Histor- of livestock guardian dogs cating animals, it has been nec- ically, humans have attempted PAGE 04 essary to protect livestock from to resolve this conflict through Livestock Guardian Dogs, wild predators. To this day, pre- a series of predator population an Ancient Tool in dation of livestock is one of the control measures including the Modern Times most prominent global hu- use of traps, hunting, and indis- PAGE 06 man-wildlife conflicts. Interest- criminate and nonselective poi- What Is the Job of a ingly, one of our most ancient soning—methods which are of- Livestock Guardian Dog? domestic companions, the dog, ten cruel and inefficient. was once a predator. One of the greatest chal- PAGE 07 The competition between lenges lies in successfully im- Breeds of Livestock man and wildlife for natural plementing effective measures Guardian Dogs spaces and resources is often that mitigate the negative im- PAGE 08 considered the main source of pacts of this conflict. It is imper- The Presence of Livestock conflict between domestic live- ative to ensure the protection of Guardian Dogs in Chile WILDLIFE BULLETIN NUMBER 2 MARCH 2017 man and his resources, includ- tion in predators is lower than PAGE 10 ing livestock, without compro- that of the United States, where Livestock in the Chacabuco Valley mising the conservation of the the losses are due to a variety of and the Transition Toward the Future Patagonia National Park native biodiversity. -

Designed by Lucas Sharp in 2013 Available in 20 Styles, Licenses For

Sharp Sans Display No.1 Designed by Lucas Sharp in 2013 Available In 20 Styles, Licenses For Web, Desktop & App 1 All Caps Roman THAI RIDGEBACK BLACK — 50PT YAKUTIAN LAIIKA EXTRABOLD —50PT PUDELPOINTERR BOLD — 50PT XOLOITZCUINTL SEMIBOLD — 50PT BULLENBEISSER MEDIUM — 50PT CHIRIBAYA DOG BOOK — 50PT SCHAPENDOES LIGHT — 50PT WELSH TERRIER THIN — 50PT BRAQUE du PUY ULTRATHIN — 50PT SAINT BERNARD Hairline —50pt Sharp Sans Display No.1 2 All Caps Italic BULL TERRIERBlack Italic — 50pt BROHOLMERExtrabold Italic — 50pt HUSKYBold Italic — 50pt DOG CHIEN-GRISSemibold Italic — 50pt SHEEPDOGMedium Italic — 50pt BRASILEIROBook Italic — 50pt LAPPHUNDLight Italic — 50pt RETRIEVERThin Italic — 50pt BULLUltrathin ItalicDOG — 50pt NIVERNAISHairline Italic — 50pt Sharp Sans Display No.1 3 All Caps Italic, Swash Alternates BRUXELLOISBlack Italic (Swash Alternates) — 50pt HIMALAYANExtrabold Italic (Swash Alternates) —50pt SHEEPDOGBold Italic (Swash Alternates) — 50pt SHIBASemibold Italic (Swash Alternates) INU — 50pt LÖWCHENMedium Italic (Swash Alternates) — 50pt MAHRATTABook Italic (Swash Alternates) — 50pt HAIRLESSLight Italic (Swash Alternates) — 50pt PINSCHERThin Italic (Swash Alternates) — 50pt BORZAYAUltrathin Italic (Swash Alternates) — 50pt KAIHairline Italic (Swash KEN Alternates) —50pt Sharp Sans Display No.1 4 Title Case Roman Norrbottenspets Black Italic — 50pt Pyrenean Mastiff Extrabold Italic — 50pt Sabueso Español Bold Italic — 50pt Braque Francais Semibold Italic — 50pt Kromfohrländer Medium Italic — 50pt Cirneco de'Etna Book Italic — 50pt -

– IPRA – Institute for the Promotion of and Research Into Guardian Animals

WOLF PREDATION AND DOMESTICATED FLOCK PROTECTION CANOVIS PROJECT / 2013-2017 ACTIVITY REPORT 2014 AND PRELIMINARY RESULTS Wolf-flock observation phase - © CanOvis – IPRA 2014 STUDY OF WOLF-FLOCK-GUARDING DOG INTERACTION TO IMPROVE FLOCK-PROTECTION DOGS AND SYSTEMS – IPRA – Institute for the Promotion of and Research into Guardian Animals December 2014 Contents INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Summary of the CanOvis Project.......................................................................................................................... 4 Activity 2014............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Areas and Partners ............................................................................................................................................ 5 The IPRA Project Team....................................................................................................................................... 6 General Information .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Reminder of Scheduled Actions (2014-2017) ................................................7 2. Organisation of Field Operations......................................................................7 3. Rationale for the -

Sudan Country Study

Pastoralism and Conservation in the Sudan Executive Summary Introduction On a global scale, Sudan perhaps ranks first in terms of pastoralists population size. About 66 per cent of Sudan is arid land, which is mainly pastoralists’ habitat. Pastoralism in the Sudan involves about 20 per cent of the population and accounts for almost 40 per cent of livestock wealth [Markakis, 1998: 41]. The livestock sector plays an important role in the economy of the Sudan, accounting for about 20 percent of the GDP, meeting the domestic demand for meat and about 70 percent of national milk requirements and contributing about 20 percent of the Sudan’s foreign exchange earnings. It is also a very significant source of employment for about 80 percent of the rural workforce. In the Sudan it is estimated that the total number of cattle multiplied 21 times between 1917 and 1977, camels 16 times, sheep 12 times and goats 8 times [Fouad Ibrahim, 1984, p.125 in Markakis, 1998: 42]. Their numbers are estimated to have doubled between 1965 and 1986. The rapid rate of animal population increase has been attributed to the introduction of veterinary services and the stimulation of the market. Two periods of exceptional rainfall (1919-1934 and 1950-1965) added momentum to this trend. In the early 1980s there were nearly three million heads of camels, over 20 million cattle, nearly 19 million sheep, and 14 million goats. Livestock estimates for the year 2005 are 38 million heads of cattle, 47 million sheep, 40 million goats and three million camels [Ministry of Animal Resources, 2006].