9 World War II in Kiribati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shyama Pagad Programme Officer, IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group

Final Report for the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Agricultural Development Compile and Review Invasive Alien Species Information Shyama Pagad Programme Officer, IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group 1 Table of Contents Glossary and Definitions ................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 1 ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Alien and Invasive Species in Kiribati .............................................................................................. 7 Key Information Sources ................................................................................................................. 7 Results of information review ......................................................................................................... 8 SECTION 2 ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Pathways of introduction and spread of invasive alien species ................................................... 10 SECTION 3 ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Kiribati and its biodiversity .......................................................................................................... -

Kiribati Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity

KIRIBATI FOURTH NATIONAL REPORT TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Aranuka Island (Gilbert Group) Picture by: Raitiata Cati Prepared by: Environment and Conservation Division - MELAD 20 th September 2010 1 Contents Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: OVERVIEW OF BIODIVERSITY, STATUS, TRENDS AND THREATS .................................................... 8 1.1 Geography and geological setting of Kiribati ......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Climate ................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Status of Biodiversity ........................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1 Soil ................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.3.2 Water Resources .......................................................................................................................... -

Participatory Diagnosis of Coastal Fisheries for North Tarawa And

Photo credit: Front cover, Aurélie Delisle/ANCORS Aurélie cover, Front credit: Photo Participatory diagnosis of coastal fisheries for North Tarawa and Butaritari island communities in the Republic of Kiribati Participatory diagnosis of coastal fisheries for North Tarawa and Butaritari island communities in the Republic of Kiribati Authors Aurélie Delisle, Ben Namakin, Tarateiti Uriam, Brooke Campbell and Quentin Hanich Citation This publication should be cited as: Delisle A, Namakin B, Uriam T, Campbell B and Hanich Q. 2016. Participatory diagnosis of coastal fisheries for North Tarawa and Butaritari island communities in the Republic of Kiribati. Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish. Program Report: 2016-24. Acknowledgments We would like to thank the financial contribution of the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research through project FIS/2012/074. We would also like to thank the staff from the Secretariat of the Pacific Community and WorldFish for their support. A special thank you goes out to staff of the Kiribati’s Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Environment, Land and Agricultural Development and to members of the five pilot Community-Based Fisheries Management (CBFM) communities in Kiribati. 2 Contents Executive summary 4 Introduction 5 Methods 9 Diagnosis 12 Summary and entry points for CBFM 36 Notes 38 References 39 Appendices 42 3 Executive summary In support of the Kiribati National Fisheries Policy 2013–2025, the ACIAR project FIS/2012/074 Improving Community-Based -

Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities Supplementary Material

FINAL DRAFT Chapter 4 Supplementary Material IPCC SR Ocean and Cryosphere Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities Supplementary Material Coordinating Lead Authors: Michael Oppenheimer (USA), Bruce Glavovic (New Zealand) Lead Authors: Jochen Hinkel (Germany), Roderik van de Wal (Netherlands), Alexandre K. Magnan (France), Amro Abd-Elgawad (Egypt), Rongshuo Cai (China), Miguel Cifuentes-Jara (Costa Rica), Robert M. Deconto (USA), Tuhin Ghosh (India), John Hay (Cook Islands), Federico Isla (Argentina), Ben Marzeion (Germany), Benoit Meyssignac (France), Zita Sebesvari (Hungary/Germany) Contributing Authors: Robbert Biesbroek (Netherlands), Maya K. Buchanan (USA), Gonéri Le Cozannet (France), Catia Domingues (Australia), Sönke Dangendorf (Germany), Petra Döll (Germany), Virginie K.E. Duvat (France), Tamsin Edwards (UK), Alexey Ekaykin (Russian Federation), Donald Forbes (Canada), James Ford (UK), Miguel D. Fortes (Philippines), Thomas Frederikse (Netherlands), Jean-Pierre Gattuso (France), Robert Kopp (USA), Erwin Lambert (Netherlands), Judy Lawrence (New Zealand), Andrew Mackintosh (New Zealand), Angélique Melet (France), Elizabeth McLeod (USA), Mark Merrifield (USA), Siddharth Narayan (US), Robert J. Nicholls (UK), Fabrice Renaud (UK), Jonathan Simm (UK), AJ Smit (South Africa), Catherine Sutherland (South Africa), Nguyen Minh Tu (Vietnam), Jon Woodruff (USA), Poh Poh Wong (Singapore), Siyuan Xian (USA) Review Editors: Ayako Abe-Ouchi (Japan), Kapil Gupta (India), Joy Pereira (Malaysia) Chapter -

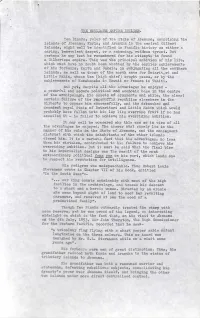

Summary of the Facts and Evidence Relating to the Massacre of British

, Name of' Accused: ~atzu Shosa, Camnander of' Japanese Forces, Tarawa, and othel' Japanese soldiers under his cOmmand T(hose identl t.y is unknoT4l. On 15th October, 1942, the f'ollowing Br1tish Nationals were beheaded, or in some instances, otherwise murdered by the Japanese at Betio, Tarawa. Lieutenant Reginald G. Morgan, Wireless Operator in the service of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony at Tarawa. Basil Cleary, Dispenser in the se~vice of' the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony at Tarawa. Isaac R. Handley, Retired Master Mariner, resident of' Tarawa. A. M. McArthur, Retired Trader of' Nonouti, Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony. Revd. A. L. Sadd, Missionary, resident of' Beru, Gilbert and Ellice. Islands Colony• The following wireless operators in the employ of' the New }:eale.nd. Government and stationed in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony. station A. C. Heenan Ma1ana Island. J. J. McCarthy Abemama II H. R. C. Hearn Kuria A. E. McKenna Honout1 II" C. A. Pearsall Tamena II The f'ollo~~ng members o-r the 2nd New Zealand Expe d1 t 1 Oll8.ry Force: Station. 64653 Pte. L. B. Speedy Mal ana 64606 u C. J. Owen Maiana 64056 D. H. Hov.'S Abemama 63882 " R. J. Hitchen Abemama 6LJ485 "II R. Jones Kuria 64382 1/ R. A. Ellis Kurla 64057 II c. A. Kllpin Nonout1 64062 1/ J. H. Nichol Nonouti 64005 " w. A. R. Parker' Tanana 64022 " R. M. McKenzie Tamana. Particulars of' the A11~ed Crime. The alleged vict 8 were stationed at or resident in various islands of' the Gilbert and Ellice Group. -

Abemama Atoll, Kiribati

Monitoring the Vulnerability and Adaptation of Coastal Fisheries to Climate Change Abemama Atoll Kiribati Assessment Report No. 2 October–November 2013 Aaranteiti Kiareti1, 2, Toaea Beiateuea2, Robinson Liu1, Tuake Teema2 and Brad Moore1 1Coastal Fisheries Programme, Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2 Kiribati Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development Funding for this project was provided by the Australian Government The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official opinion of the Australian Government © Copyright Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2015 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) acknowledges with gratitude the funding support provided by the Australia’s International Climate Change Adaptation Initiative (ICCAI) for the implementation of the ‘Monitoring the Vulnerability and Adaptation of Coastal Fisheries to Climate Change’ project in Abemama Atoll, Kiribati. SPC also gratefully acknowledges the collaborative support from the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development. In particular, we are especially thankful to Raikaon Tumoa (Director) and Karibanang Tamuera (Principle Fisheries Officer) who showed interest in the importance of this project and provided the needed support in moving the project forward. -

Republic of Kiribati WHO Library Cataloguing-In-Publication Data

Human Resources for Health Country Profiles Republic of Kiribati WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Human resources for health country profiles: Republic of Kiribati 1. Delivery of healthcare – manpower. 2. Health manpower - education. 3. Health resources - utilization. I. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. ISBN 978 92 9061 668 9 (NLM Classification: W76 LA1) © World Health Organization 2014 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (www.who.int/about/licensing/ copyright_form/en/index.html). For WHO Western Pacific Regional Publications, request for permission to reproduce should be addressed to Publications Office, World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, P.O. Box 2932, 1000, Manila, Philippines, fax: +632 521 1036, e-mail: [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. -

North Tarawa Social and Economic Report 2008 2 of 2

- 41 - 3.5.7. Community involvement to improve standard of education Normally the community does not interfere with the school curriculum, as it is the responsibility of Government to design them to suit the ages being taught to and ensure their effective implementation. However the community, through the school committee, often takes the initiative to address a wide range of other issues, such as children and teachers comfort, security, staffing, sports, and even school infrastructure. In a lot of cases, the teachers have to take the initiative and assign each pupil a specific task to do for a class activity or a school project at which times, the children always seek and are given help and support from families. This kind of help and support from individual families can take the form of money, food or their own involvement such as in the building of a school ‘mwaneaba’ or singing in a school dancing practice and competition etc. Over the past years the community has assisted both the primary and junior secondary schools especially in performing critical maintenance work on classrooms, offices and teacher residences. These buildings are by right the responsibility of Government who, in many cases has been very slow in providing the financial support needed to keep school infrastructure in good shape. North Tarawa is not an exception in these slow provisions of financial support from the Government, Despite this, the community continue to support their school children and their schools by being guardians of the school property as well as in provision of pupil/student’s school needs for school activities or other school requirements as may arise from time to time. -

Suva and Lautoka

WHO WE ARE: • Pacific Direct Line (PDL) is a Shipping Company specialising in providing liner shipper services to the South Pacific Region. • We have been trading in the region for over 40 years • The Company has been owned and managed by the same family since it’s formation and prides itself on the close family bond which is the backbone of the company and all its subsidiary businesses. • In 2006 PDL sold 51% of the business to Pacific International Line (PIL) in Singapore. • Our core business has been to provide shipping services from New Zealand and Australia to the Pacific Islands, but we have repositioned the business over the last five years to also provide feedering services for various international operators. WHAT WE DO: • We offer liner shipping services to 16 countries and 22 ports including Fiji, (Suva and Lautoka) Samoa, American Samoa, Tonga, (Nuku’alofa), Wallis and Futuna, Funafuti, Vanuatu, ( Port Vila and Santo) New Caledonia, Tahiti, the Cook Islands (Rarotonga), Norfolk, Tarawa and Majuro. • PDL owns Transam Agencies throughout the Pacific, ensuring consistent standards and levels of service across the region. (see attached) • Our fleet of vessels are chartered mainly from our parent company, (PIL) and we are constantly upgrading our fleet to larger brand new vessels purpose built for this unique trade. This advantage allows us to select our vessels to cater for the growth in the volume from the influx of transhipment containers to the South Pacific. • We are developing “bolt on” businesses ensuring vertical integration of our services across cartage, consolidation, stevedoring, container depots… • PDL employs approximately 300 people throughout the Pacific in our shipping, agency and subsidiary companies. -

SPX Schedule EB

South Pacific Express Connection Schedule EASTBOUND SAILINGS September 2021 - December 2021 Connecting the South Pacific with the US September 21, 2021 Origin Vessel | Auckland | Nuku'alofa | Lautoka | Suva Eastbound Sailings │Papeete | Pago Pago │ Apia │ Nukualofa | Honolulu │ US West Coast Origin Vessel Auckland Nukualofa Lautoka Suva Apia Arrivals Papeete Pago Pago Apia Long Beach Oakland Honolulu Manoa 444W Imua 106 Arkadia 531 Sailed 9/15 Sailed 9/20 Wed, 22-Sep Thu, 23-Sep Tue, 28-Sep Fri, 24-Sep Thu, 30-Sep Wed, 29-Sep Thu, 14-Oct Sat, 16-Oct Sat, 23-Oct Manoa 445W Olomana 134 Cap Salia 967 Mon, 27-Sep Sun, 3-Oct Omit Tue, 5-Oct Sun, 10-Oct Mon, 11-Oct Sat, 16-Oct Sat, 16-Oct Sat, 30-Oct Mon, 1-Nov Sat, 6-Nov R J Pfeiffer 486W Imua 107 Arkadia 532 Wed, 13-Oct Tue, 19-Oct Thu, 21-Oct Fri, 22-Oct Wed, 27-Oct Wed, 27-Oct Tue, 2-Nov Mon, 1-Nov Tue, 16-Nov Thu, 18-Nov Sat, 27-Nov Olomana 135 Cap Salia 968 Wed, 27-Oct Tue, 2-Nov Omit Thu, 4-Nov Tue, 9-Nov Fri, 12-Nov Wed, 17-Nov Wed, 17-Nov Thu, 2-Dec Sat, 4-Dec Imua 108 Arkadia 533 Wed, 17-Nov Tue, 23-Nov Thu, 25-Nov Fri, 26-Nov Wed, 1-Dec Mon, 29-Nov Sat, 4-Dec Sat, 4-Dec Sun, 19-Dec Tue, 21-Dec 1 Agents and Offices U.S. Ports Pago Pago, American Samoa Papeete, Tahiti Matson Customer Service Center Molida Shipping Agency, Ltd Papeete Seairland Transports Tel: 1-866-662-4826 Tel: (684) 633-2777 Tel: (689) 40549700 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Apia, Samoa Nukualofa, Tonga Christmas Island Molida Shipping Agency, Ltd. -

^ Distrust with Which the Inhabitants of the Other Islands 7"* Viewed Him

THE WOULi>-BE El-IPIRE BUILDER-. Tem Binoka, ruler of the State of Ahemama, comprising the isla-nds of Ahemama, Kuria, and Aranuka in the central Gilbert Islands, might well he identified in Pacific history as either a caring, benevolent despot, or a scheming, rutliless tyrant. But perhaps he may best be remembered for his attempts to found a Gilbertese empire. This was the principal ambition of his life, , which must have no doubt been vjhetted by the earlier achievements -•<7 '• oi* liis forbears, Kaitu and Uakeia, in subjugating all the southern islands, as well as those of the north save for Butaritj^ri and Little Makin, whose Uea (high chief) sought peace, or by the achievements of Kamehameha ir Hawaii or Poraare in Tahiti. And yet, despite all the advantages he enjoyed - a powerful and secure political and economic base in the centre of the archipelago, his assets of armaments and ships, the almost certain failure of the ragamuffin republics elsevjhere in the Gilberts to oppose him successfully, and the d.ebauched g^nd decadent royal State of Butaritari and Little Makin vjhich would probably have fallen into his la.p like overripe fruit if he had assailed it - he failed to achieve his overriding ambition. : It may well be v/ondered why this was so in view of all ! , ,i-7 the advantages he enjoyed. The answer must surely lie in the i manner of his rule in the State of Ahemama, and the consequent ^ distrust with which the inhabitants of the other islands 7"* viewed him. It is a curious fact that his advantages, no less then his mistakes, contributed to his failure to achieve his r • • overriding ambition. -

WWII in Tuvalu

World War II in Tuvalu NELI LEFUKA'S WAR YEARS IN FUNAFUTI This Chapter is from Logs in the Currents of the Sea , Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1978. The book is about Neli Lifuka's account of the Vaitupu colonists of Kioa island in Fiji. One day, in 1941, we received a telegram that the Japanese had dropped bombs on Ocean Island [within two days after Pearl Harbor]. A few months later we saw airplanes for the first time, and soon afterwards we received another telegram from Colonel Fox-Strangways, the Resident Commissioner of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony. It was an order to dig foxholes. Later, Mr. Fox-Strangways came to Vaitupu with his people to show us how to dig foxholes and how to fall down if any bombs were dropped on the village. We knew about the war from the wireless. The wireless also had the BBC news, so we could hear what was going on. Our magistrate, Peni, organized everything. He asked the people to build three canoes, each for ten men. These canoes had to be out on the sea day and night to watch out for ships and planes. If they saw anything they would come back to the island and the magistrate could call Funafuti on the wireless. That's what we did. I built a house in the bush on the east side of the village because I had been appointed to watch the sea from there. After a few months we saw planes flying very low. They had big stars on their wings.