Recent Developments in Animal Tort and Insurance Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Canadian Veterinary Journal La Revue Vétérinaire Canadienne Biosecurity Practices in Western Canadian Cow-Calf Herds and Their Association with Animal Health

July/Juillet 2021 July/Juillet The Canadian Veterinary Journal Vol. 62, No. 07 Vol. La Revue vétérinaire canadienne July/Juillet 2021 Volume 62, No. 07 The Canadian Veterinary Journal Canadian Veterinary The Biosecurity practices in western Canadian cow-calf herds and their association with animal health Computed tomographic characteristics of cavitary pulmonary adenocarcinoma in 3 dogs and 2 cats Bordetella bronchiseptica-reactive antibodies in Canadian polar bears La Revue vétérinaire canadienneLa Revue vétérinaire Evaluation of platelet-rich plasma applied in the coronary band of healthy equine hooves Diagnosis and outcome of nasal polyposis in 23 dogs treated medically or by endoscopic debridement Sabulous cystitis in the horse: 13 cases (2013–2020) Presumed acquired dynamic pectus excavatum in a cat Computed tomographic diagnosis of necroulcerative reticulorumenitis with portal venous gas in a lamb 2020 CVMA ANNUAL REPORT RAPPORT ANNUEL 2020 DE L’ACMV FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY Your Future is Bright and Full of Opportunity At VetStrategy, we live our passion every day. It’s a place where uniqueness is embraced, personal development is encouraged, and a supportive team is behind you. Whether you are a veterinary clinic owner looking to be part of something bigger or an animal health professional seeking a new career challenge, VetStrategy wants to hear from you. LET’S START THE CONVERSATION Looking to grow your existing Looking for career opportunities? vet practice? Contact us at: Contact us at: [email protected] [email protected] FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY Protecting Veterinarians Since 2005 A specialized insurance program for the Canadian veterinary industry. Professional Liability | Commercial Insurance | Employee Benefits Join now and receive preferred member pricing on Commercial Insurance and Employee Benefits! Available exclusively to members of the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. -

Nova Scotia Veterinary Medical Association Council

G^r? NOVA SCOTIAVETERINARY MEDICAL ASSOCIATION Registrar's Office 15 Cobequid Road, Lower Sackvllle, NS B4C 2M9 Phone: (902) 865-1876 Fax: (902) 865-2001 E-mail: [email protected] September 24, 2018 Dear Chair, and committee members, My name is Dr Melissa Burgoyne. I am a small animal veterinarian and clinic owner in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia. I am currently serving my 6th year as a member of the NSVMA Council and currently, I am the past president on the Nova Scotia Veterinary Medical Association Council. I am writing today to express our support of Bill 27 and what it represents to support and advocate for those that cannot do so for themselves. As veterinarians, we all went into veterinary medicine because we want to.help animals, prevent and alleviate suffering. We want to reassure the public that veterinarians are humane professionals who are committed to doing what is best for animals, rather than being motivated by financial reasons. We have Dr. Martell-Moran's paper (see attached) related to declawing, which shows that there are significant and negative effects on behavior, as well as chronic pain. His conclusions indicate that feline declaw which is the removal of the distal phalanx, not just the nail, is associated with a significant increase in the odds of adverse behaviors such as biting, aggression, inappropriate elimination and back pain. The CVMA, AAFP, AVMA and Cat Healthy all oppose this procedure. The Cat Fancier's Association decried it 6 years ago. Asfor the other medically unnecessary cosmetic surgeries, I offer the following based on the Mills article. -

Reel-To-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

Reel-to-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alan Campbell, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Barry Shank 1 Copyrighted by Matthew Alan Campbell 2019 2 Abstract For members of the United States Armed Forces, communicating with one’s loved ones has taken many forms, employing every available medium from the telegraph to Twitter. My project examines one particular mode of exchange—“audio letters”—during one of the US military’s most trying and traumatic periods, the Vietnam War. By making possible the transmission of the embodied voice, experiential soundscapes, and personalized popular culture to zones generally restricted to purely written or typed correspondence, these recordings enabled forms of romantic, platonic, and familial intimacy beyond that of the written word. More specifically, I will examine the impact of war and its sustained separations on the creative and improvisational use of prosthetic culture, technologies that allow human beings to extend and manipulate aspects of their person beyond their own bodies. Reel-to-reel was part of a constellation of amateur recording technologies, including Super 8mm film, Polaroid photography, and the Kodak slide carousel, which, for the first time, allowed average Americans the ability to capture, reify, and share their life experiences in multiple modalities, resulting in the construction of a set of media-inflected subjectivities (at home) and intimate intersubjectivities developed across spatiotemporal divides. -

Devocalization Fact Sheet

Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association Devocalization Fact Sheet Views of humane treatment of animals in both the veterinary profession and our society as a whole are evolving. Many practicing clinicians are refusing to perform non‐therapeutic surgeries such as devocalization, declawing, ear cropping and tail docking of dogs and cats because these procedures provide no medical benefit to the animals and are done purely for the convenience or cosmetic preferences of the caregiver. At this point, devocalization procedures are not widely included in veterinary medical school curricula. What is partial devocalization? What is total devocalization? The veterinary medical term for the devocalization procedure is ventriculocordectomy. When the surgery is performed for the non‐therapeutic purpose of pet owner convenience, the goal is to muffle or eliminate dog barking or cat meowing. Ventriculocordectomy refers to the surgical removal of the vocal cords. They are composed of ligament and muscle, covered with mucosal tissue. Partial devocalization refers to removal of only a portion of the vocal cords. Total devocalization refers to removal of a major portion of the vocal cords. How are these procedures performed? Vocal cord removal is not a minor surgery by any means. It is an invasive procedure with the inherent risks of anesthesia, infection, blood loss and other serious complications. Furthermore, it does not appear to have a high efficacy rate since many patients have the procedure performed more than once, either to try to obtain more definitive vocal results or to correct unintentional consequences of their previous surgeries. Often only the volume and/or pitch of animals’ voices are changed by these procedures. -

Devocalization Procedures on Dogs and Cats

Contact: Maria Cilenti - Director of Legislative Affairs - [email protected] - (212) 382-6655 REPORT ON LEGISLATION BY THE ANIMAL LAW COMMITTEE A.1204 M. of A. Zebrowski S.2271 Sen. Grisanti AN ACT to amend the agriculture and markets law, in relation to restricting the performance of surgical devocalization procedures on dogs and cats. THIS LEGISLATION IS APPROVED WITH RECOMMENDATIONS 1. SUMMARY OF THE PROPOSED LAW A.1204/S.2271 (“the bill”) adds a new section 365-a to the Agriculture & Markets Law that would impose new restrictions on ventriculocordectomy (commonly referred to as “devocalization surgery”), a surgical procedure that reduces or eliminates a dog’s or a cat’s ability to produce vocal sounds. It would also establish record keeping requirements in connection with devocalization surgery. Specifically, the bill provides that devocalization surgery may be performed only by a licensed veterinarian and only when medically necessary to relieve the dog or cat from pain or harm. Where this surgery is performed, a veterinarian must include information about the procedure in the animal's treatment record.1 The veterinarian is also required to annually report to the Commissioner of Education the number of such surgeries he or she performed. Violation of the law by any person who performs the devocalization surgery or knowingly caused the surgery to be performed is a Class B misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment for up to 90 days and/or a fine of up to $500. A veterinarian’s license may be suspended or revoked upon the finding of a violation. 1 NY Education Law § 6714 provides that veterinary treatment records shall be provided to the owner of an animal upon written request and that such records may also be reported or disclosed to law enforcement “[w]hen a veterinarian reasonably and in good faith suspects that a companion animal’s injury, illness or condition is the result of animal cruelty or a violation of any state or federal law pertaining to the care, treatment, abuse or neglect of a companion animal.”. -

The Canadian Veterinary Journal La Revue Vétérinaire Canadienne The

July/Juillet 2016 July/Juillet The Canadian Veterinary Journal Vol. 57, No. 07 57, Vol. La Revue vétérinaire canadienne July/Juillet 2016 Volume 57, No. 07 The cost of a case of subclinical ketosis in Canadian dairy herds Economic value of ionophores and propylene glycol to prevent disease and treat ketosis in Canada Comparison of intraoperative and postoperative pain during canine ovariohysterectomy and ovariectomy Evolution of in vitro antimicrobial resistance in an equine hospital over 3 decades Presumed masitinib-induced nephrotic syndrome and azotemia in a dog Hypoadrenocorticism mimicking protein- losing enteropathy in 4 dogs Total laryngectomy for management of chronic aspiration pneumonia in a myopathic dog Citrobacter freundii induced endocarditis in a yearling colt Equine motor neuron disease in 2 horses from Saskatchewan Diagnostic performance of an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect bovine leukemia virus antibodies in bulk-tank milk samples Congenital nutritional myodegeneration in a neonatal foal 2015 CVMA ANNUAL REPORT RAPPORT ANNUEL 2015 DE L’ACMV FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY Dual Validation. For your peace of mind. Purina Testing APR Nestlé S.A. owned by Société des Produits Purina trademarks are Standard Testing 2x RSS NEW! When you’re evaluating a diet, science matters. It matters to us, too. That’s why our NEW UR Urinary ® Ox/St™ Canine Formula, along with our entire urinary therapeutic diet portfolio, is backed by a comprehensive dual-validation process, measuring both the concentration and activity of the minerals that produce sterile struvite and calcium oxalate crystals. It’s the nutrition your clients need, backed by science and expertise you can trust. -

Animal Crimes Bill

PROHIBIT THE DEVOCALIZATION OF CATS AND DOGS UNLESS MEDICALLY NECESSARY A.1679 Member of Assembly Zebrowski S.4647 Senator Avella AN ACT to amend the agriculture and markets law, in relation to restricting the performance of surgical devocalization procedures on dogs and cats This bill prohibits devocalization of dogs and cats except when the procedure is medically necessary to treat or relieve an illness, disease or injury or to correct a congenital abnormality, suffered by the animal where the illness, disease, injury or congenital abnormality causes the animal physical pain or harm. BACKGROUND Sometimes dogs and cats must undergo vocal cord surgery to treat disease, such as cancer, or to correct a birth defect. But when performed for the sole purpose of suppressing the animal’s voice, it is widely considered an act of cruelty. It is banned throughout the UK, in Massachusetts, and by local ordinance in Warwick, Rhode Island. Devocalization subjects animals to many risks and potential complications, some life threatening. Animals receive no benefit. Devocalization is ordered strictly for convenience or profit of cat or dog breeding businesses, or a hobby involving breeding dogs or cats. SUMMARY OF PROPOSED BILL This bill prohibits devocalization of dogs and cats except when the procedure is medically necessary. “Medically necessary” refers solely to physical conditions. These provisions cannot be construed to allow for any “behavioral” conditions. Performing devocalization of a dog or cat, or causing devocalization to be performed in violation of the provisions of this law, shall be punishable by imprisonment for one year or a fine of up to five thousand dollars or both. -

LOWER URINARY TRACT DISEASE a REVIEW Minimalism Can Be Magnificent

DECEMBER 2015 | No 21 THE WILDLIFE REHABILITATION NETWORK OF BC PERIODONTAL DISEASE IN A NUTSHELL ELP — TWO VIEWS VETAVISION 2015 & THE FISTULATED COW REVISIONS TO THE PCA ACT FELINE LOWER URINARY TRACT DISEASE A REVIEW minimalism can be magniFicent. H! The ULTRA™ line of 0.5 mL vaccines* offers pet EA owners exactly what they want for their pet – safe, Dogs are impressed. effective protection with minimal injection volume. h y A more comfortable vaccine experience… now that’s a beautiful thing. BRONCHI-SHIELD® ORAL is making a happy vaccine experience the Contact your Boehringer Ingelheim (Canada) Ltd. sales new normal. representative to learn more about ULTRA™ Duramune® BRONCHI-SHIELD® ORAL is the first to and ULTRA™ Fel-O-Vax®. redefine Bordetella vaccination without needle sticks, sneeze-backs, or initial boosters!1 Give dogs and their owners an enjoyable vaccine experience—only with BRONCHI-SHIELD ® ORAL. * The ULTRA vaccine line includes ULTRA DURAMUNE and ULTRA FEL-O-VAX. ULTRA DURAMUNE and ULTRA FEL-O-VAX are registered trademarks of Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc. BRONCHI-SHIELD is a registered trademark of Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc. © 2015 Boehringer Ingelheim (Canada) Ltd. Reference: 1. Data on file, BRONCHI-SHIELD ORAL package insert, Boehringer Ingelheim (Canada) Ltd. © 2015 Boehringer Ingelheim (Canada) Ltd. from the editor i have a question his issue, by chance and not by design, includes a lot of infor- elcome to this new occasional column. If you have questions about interesting or sen- mation about wildlife in BC, maybe because human interactions sitive veterinary issues, send them to the CVMA-SBCV Chapter. -

Table of Contents

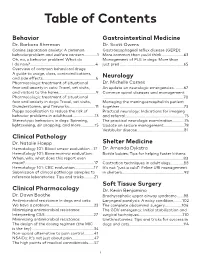

Table of Contents Behavior Gastrointestinal Medicine Dr. Barbara Sherman Dr. Scott Owens Canine separation anxiety: A common Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): behaviorproblem and welfare concern.............1 More common than you’d think .....................63 Oh, no, a behavior problem! What do Management of PLE in dogs: More than I do now?................................................................4 just pred ..............................................................65 Overview of common behavioral drugs: A guide to usage, class, contraindications, and side effects....................................................6 Neurology Pharmacologic treatment of situational Dr. Michelle Carnes fear and anxiety in cats: Travel, vet visits, An update on neurologic emergencies..........67 and visitors to the home.....................................9 Common spinal diseases and management Pharmacologic treatment of situational ...............................................................................70 fear and anxiety in dogs: Travel, vet visits, Managing the meningoencephalitis patient thunderstorms, and fireworks..........................11 together ..............................................................73 Puppy socialization to reduce the risk of Practical neurology: Indications for imaging behavior problems in adulthood......................13 and referral..........................................................75 Stereotypic behaviors in dogs: Spinning, The practical neurologic examination............76 lightseeking, -

Canine Tail Injuries in New Zealand: Causes, Treatments and Risk Factors and the Prophylactic Justification for Canine Tail Docking

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Canine tail injuries in New Zealand: Causes, treatments and risk factors and the prophylactic justification for canine tail docking. A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Veterinary Studies Institute of Veterinary, Animal and Biomedical Sciences Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Amber Wells 2013 i Acknowledgements Thanks to supervisors Kate Hill, Daan Vink and Kevin Stafford. I would like to thank Vivienne Lintott and Iain Gordon of Provet for writing the SQL script that made data collection on this scale possible, for providing detailed instructions for clinic staff, and for your always cheerful and swift responses to my various queries. A big thanks to the veterinary clinics that allowed me access to the information I needed to complete this thesis, particularly the VisionVPM pros more often than not found at reception. Thank you to the New Zealand Veterinary Association’s Companion Animal Society for their support and input into the original idea for this research thesis. Thanks also to Mrs Berys Clark for the financial assistance provided to me through the Lovell and Berys Clark scholarships I received in 2011 and 2012. To my partner Oskar, who I somehow found the time to “civilly unite with” during this year, thank you for your support over the past two years and of course, every year before that, and for the many to come. -

![Annual Report 2010 [ Table of Contents ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0047/annual-report-2010-table-of-contents-2610047.webp)

Annual Report 2010 [ Table of Contents ]

[ Stay Connected! ] Keep in touch with our rescue and advocacy work year-round: Follow us on Facebook and Twitter Download our HumaneTV app for iPhone, iPad, and Android Read our award-winning magazine, All Animals Stop by A Humane Nation, the blog of HSUS president and CEO Wayne Pacelle Learn more at humanesociety.org. Celebrating Animals, Confronting Cruelty The Humane Society of the United States Annual Report 2010 [ Table of Contents ] [ 2010 Key Accomplishments ] In Their Words 8 34 22 HSUS animal care centers provide emergency treatment and “This is a subject sanctuary to nearly 16,000 animals, while our veterinary clinics and wildlife experts rescue and treat thousands more that I am extremely passionate about. By Federal bills to strengthen shark finning ban and working together, we prohibit crush videos are signed into law can find good homes for millions of adopt- Five HSUS undercover investigations expose horrific able, homeless, and abuses at industrial egg, pork, and turkey facilities abandoned pets.” —Ellen DeGeneres, a longtime HSUS supporter Humane Society International launches a ground- who worked with us to provide 1 million servings of Halo pet food to shelter animals during the Postal breaking initiative in Haiti, including spay/neuter, Service’s Stamps to the Rescue campaign disaster response, and veterinary training programs HSUS teams deploy to 51 emergency rescues, saving nearly “I was troubled to Compassionate Farmer: Bruce Hero for Puppies: After seeing for The Accidental Activist: When 11,000 animals from puppy -

Statements of Position Mission to Further the Compassionate, Safe, and Responsible Relationship Between Animals and People

Statements of Position Mission To further the compassionate, safe, and responsible relationship between animals and people. Vision Larimer Humane Society is valued as an essential component to the high quality of life for animals and people in Northern Colorado. Values Open Admission As an open door shelter, we believe all animals deserve a safe haven and to have their care and treatment guided by the Five Freedoms. Community We believe that by harnessing the power and collaboration of the community, guided by our knowledge and leadership in animal welfare, we can better support animals together. Service We believe that our role is to serve our community, both animals and people, with respect, dignity and compassion. Trust We believe that by building a foundation of trust in the communities we serve, our organization can thrive and we will be well positioned to fulfill our mission. People We value the time, thoughts and talents of the staff and people in our community, including volunteers, supporters and our partners. Responsibility We have a responsibility to think progressively, accept responsibility for our actions, ensure existing laws are enforced, and to be good stewards of the resources we have, all to improve the lives of the animals and communities we serve. Positions Animal Control Larimer Humane Society believes that comprehensive, progressive, and effectively administered animal-control programs are essential to the protection of animals. Such programs lead to a reduction in animal suffering by helping to reduce pet overpopulation and decrease the incidence of animal injury and abuse. Furthermore, these programs improve public health and safety by reducing the number of animal bites and providing greater control over the spread of rabies and other diseases.