Univerzitet Umetnosti U Beogradu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Doppelte Singles

INTERPRET A - TITEL B - TITEL JAHR LAND FIRMA NUMMER 10 CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY NOTHING CAN 1978 D MERCURY 6008 035 10 CC GOOD MORNING JUDGE DON'T SQUEEZE 1977 D MERCURY 6008 025 10 CC I'M MANDY FLY ME HOW DARE YOU 1975 D MERCURY 6008 019 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE GOOD NEWS 1975 D MERCURY 6008 014 2 PLUS 1 EASY COME, EASY GO CALICO GIRL 1979 D PHONOGRAM 6198 277 3 BESOFFSKIS EIN SCHÖNER WEISSER ARSCH LACHEN IST 0D FLOWER BMB 2057 3 BESOFFSKIS HAST DU WEINBRAND IN DER BLUTBAHN EIN SCHEICH IM 0 D FLOWER 2131 3 BESOFFSKIS PUFF VON BARCELONA SYBILLE 0D FLOWER BMB 2070 3 COLONIAS DIE AUFE DAUER (DAT MALOCHELIED) UND GEH'N DIE 1985 D ODEON 20 0932 3 COLONIAS DIE BIER UND 'NEN APPELKORN WIR FAHREN NACH 0 D COLONGE 13 232 3 COLONIAS DIE ES WAR IN KÖNIGSWINTER IN D'R PHILHAR. 1988 D PAPAGAYO 1 59583 7 3 COLONIAS DIE IN AFRICA IST MUTTERTAG WIR MACHEN 1984 D ODEON 20 0400 3 COLONIAS DIE IN UNS'RER BADEWANN DO SCHWEMB HEY,ESMERALDA 1981 D METRONOME 30 401 3 MECKYS GEH' ALTE SCHAU ME NET SO HAGENBRUNNER 0 D ELITE SPEC F 4073 38 SPECIAL TEACHER TEACHER (FILMM.) TWENTIETH CENT. 1983 D CAPITOL 20 0375 7 49 ERS GIRL TO GIRL MEGAMIX 0 D BCM 7445 5000 VOLTS I'M ON FIRE BYE LOVE 1975 D EPIC EPC S 3359 5000 VOLTS I'M ON FIRE (AIRBUS) (A.H.) BYE LOVE 1975 D EPIC EPC S 3359 5000 VOLTS MOTION MAN LOOK OUT,I'M 1976 D EPIC EPC S 3926 5TH DIMENSION AQUARIUS DON'T CHA HEAR 1969 D LIBERTY 15 193 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS WISHING COMMITTED 1982 D JIVE 6 13 640 A LA CARTE DOCTOR,DOCTOR IT WAS A NIGHT 1979 D HANSA 101 080 A LA CARTE IN THE SUMMER SUN OF GREECE CUBATAO 1982 D COCONUT -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Amanda Lear with Love Mp3, Flac, Wma

Amanda Lear With Love mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: With Love Country: Russia Released: 2006 Style: Chanson MP3 version RAR size: 1937 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1741 mb WMA version RAR size: 1558 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 614 Other Formats: ASF AA MP4 MMF MPC AU VOX Tracklist Hide Credits 1 C'est Magnifique 2:29 2 Whatever Lola Wants 3:07 3 Is That All There Is? 4:25 Love For Sale 4 3:36 Keyboards, Programmed By [Programmations] – Alain Bernard 5 I'm In The Mood For Love 3:49 6 My Baby Just Cares For Me 3:38 7 Si La Photo Est Bonne 2:54 8 Johnny 3:05 9 Bambino 3:20 10 Senza Fine 3:17 11 Kiss Me Honey Kiss Me 2:36 12 Déshabillez-moi 4:19 Bonus Track 13 Johnny (Live Version) 2:50 Credits Backing Vocals – Yves Martin Backing Vocals, Producer [Music], Arranged By – Leonard Raponi* Concept By [Concept + Titles Selection] – Amanda Lear Concertmaster – Lionel Campano Design – Aurélien Tourette, Vincent Malléa Drums, Percussion – Christophe Gallizio Engineer [Pro-tools Assistant] – Romain Joubert Engineer [Sound] – Vincent Lépée Keyboards, Programmed By [Programmations] – Leonard Raponi* (tracks: 1 to 3, 5 to 13) Other [Amanda Lear's Hairstyle By] – Christophe at Calude-Maxime, Paris Photography By – Julien Daguet Piano – Pierre Bertrand Producer – Alain Mendiburu, Yvon Chateigner Producer [Production Assistant] – Jun Adashi Notes Recorded between May and August 2006 at Blue Sound Studio, Levalois-Perret and LR Studio, Villeneuve Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 090204969302 Matrix / Runout: LDR 3735 AM LE070217 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year DST 77065-2 Amanda Lear With Love (CD, Album) Dance Street DST 77065-2 Europe 2006 With Love (CD, Album, YC 151166 Amanda Lear Edina YC 151166 Russia 2006 Unofficial) Amour Toujours (CD, COM 1185-2 Amanda Lear S.A.I.F.A.M. -

PR Info Love Tree Neu Engl

The SHARING HERITAGE Love Tree Ensemble Mitglieder des Ensembles bei der ersten Session in Hven, Schweden: Harald Haugaard, Mattias Peréz , Helene Blum, Tapani Varis, Julia Lacherstorfer, Nataša Mirković, Sérgio Crisóstomo, Etta Scollo (v.l.n.r.), Copyright: Still Words Photography Eleven outstanding musicians from all over Europe invite you to experience astonishing facets of European folk music in an extraordinary concert. After all, in 2018 Europe is celebrating its diverse cultural traditions – and the motto chosen by the EU is ‘SHARING HERITAGE’. Singer Helene Blum and violinist Harald Haugaard, two of the world’s most popular Danish musicians, have launched the SHARING HERITAGE Love Tree Ensemble in their roles as ambassadors of the European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018. The artists involved embody very different musical traditions from Finnish Karelia, Northern Ireland and the High Tatras to the Alps, Sicily and Portugal. The ensemble has gathered age-old songs and melodies from all directions, revealed their common origins, and breathed new life into them. With their similarities being unmistakable, regional heritage and a profoundly European vision can be heard to flow together. The same song known to Scots as a jig (actually derived from the French ‘gigue’) is also a nursery rhyme in Denmark and a tarantella in Italy. Even ‘The Love Tree’, the tune after which the band was named, has made its way around Europe for centuries in various guises. Known as ‘Folia’ in Portugal and Spain, in Danish it’s called ‘Kærlighedstræet’. In this simple love song in three-four time, the various versions of the lyrics usually deal with transience and pride. -

167558354.Pdf

ngelina Jolie (/dʒoʊˈliː/ joh-LEE, born Angelina Jolie Voight; June 4, 1975) is an American actress, film director, and screenwriter. She has received an Academy Award, two Screen Actors Guild Awards, and three Golden Globe Awards, and was named Hollywood's highest-paid actress by Forbes in 2009 and 2011.[2][3] Jolie promotes humanitarian causes, and is noted for her work with refugees as a Special Envoy and former Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). She has often been cited as the world's "most beautiful" woman, a title for which she has received substantial media attention.[4][5][6][7] Jolie made her screen debut as a child alongside her father Jon Voight in Lookin' to Get Out (1982), but her film career began in earnest a decade later with the low-budget production Cyborg 2 (1993). Her first leading role in a major film was in the cyber- thrillerHackers (1995). She starred in the critically acclaimed biographical television films George Wallace (1997) and Gia (1998), and won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in the drama Girl, Interrupted (1999). Jolie achieved wide fame after her portrayal of the video game heroine Lara Croft in Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001), and established herself among the highest-paid actresses in Hollywood with the sequel The Cradle of Life (2003).[8] She continued her action star career with Mr. & Mrs. Smith (2005), Wanted (2008), and Salt (2010)—her biggest live-action commercial successes to date[9]—and received further critical acclaim for her performances in the dramas A Mighty Heart (2007) and Changeling (2008), which earned her a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Actress. -

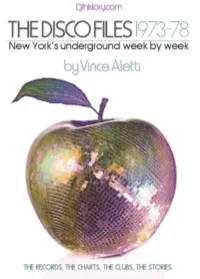

The Disco Files Template

THE DISCO F ILES 1973-78 New York’s Underground, Week by Week by Vince Aletti xxx xxx Rolling Stone August 28, 1975 Dancing Madness By Vince Aletti NEW YORK – It’s not easy to pin down the disco craze with figures. As one independent mixer of disco singles explained, “The numbers are growing so fast. Every day I get four or five invitations to grand openings of new clubs.” But even the rough estimates of disco scene observers are revealing: 2000 discos from coast to coast, 200 to 300 in New York alone – the uncrowned capital of dancing madness, where an estimated 200,000 dancers make the weekly club pilgrimage. And when disco people like a record, it can become a hit-regardless of radio play. Take Consumer Rapport’s “Ease On down The Road.” Released on tiny Wing and a Prayer Records, it sold more than 100,000 copies in New York in its first two weeks before it was picked up on the radio. Discos and what has come to be known as disco music have turned out to be, if not the Next Big Thing everyone in the music business was waiting for, then the closest thing to it in years. Discos have opened in old warehouses, steak restaurants, unused hotel ballrooms and singles bars... any place you could stick a ceiling full of flashing, colored lights, a mirrored ball, two turntables, a battery of speakers, a mixer and a DJ. In a recession economy, they’re a bargain both for the club owner – who has few expenses after his initial setup investment and an average $50-a-night salary to the DJ – and the patrons, who can dance nonstop all night for a fraction of the cost of a concert ticket. -

March CALENDAR of EVENTS

March CALENDAR #!"$ @7 EVENTS "EEJTPO4USFFUt#FSLFMFZ $BMJGPSOJBt tXXXGSFJHIUBOETBMWBHFPSH SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY ALL SHOWS ARE GENERAL ADMISSION DOORS @ 7 PM, MUSIC @ 8 PM (UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED) TICKET DISCOUNTS: Tin Solas YOUTH-HALF PRICE T`^aV]]Z_X]jUcZgZ_X Hat 4V]eZT^fdZT (AGES 25 & UNDER) dVUfTeZgV SENIOR-$2.00 OFF TYR^SVc[Rkk (AGES 65 & OVER) WINTER II SERIES CLASSES BEGIN THE WEEK OF MARCH 11 MEMBERS-$2.00 OFF #%&!RUg #'&!RUg GUITARtBANJOtUKULELEtMANDOLIN #'&!U``c Mar 1 #)&!U``c Mar 2 Jewish Music Festival Jewish Music Festival Masters of Real Vocal Freight Erin Theodore Bikel, Tradition Young Women’s Open Mic Merima Kljuco Martin Hayes, Chorus String ground zero of the McKeown Dennis Cahill, hootenanny revival ViacVddZgV & Shura Lipovsky Iarla Ó Lionáird, Quartet, WVZdejW`]\c``ed SV]`gVURTe`c with Keith Terry Holcombe Waller W`]\dZ_XVcgZcef`d` Máirtín O’Connor, True Life Trio `aV_d RTT`cUZ`_Zde Cathal Hayden, & Crosspulse RWVRde`W;VhZdY JZUUZdYd`_XdecVdd f_ZbfVg`TR]S`Uj h`c]U^fdZT Seamie O’Dowd, cYjeY^T`]]RS`cReZ`_ David Power ##&! #%&! >Rc$ %&! '&! Mar 5 #!&! ##&! Mar 6 #)&! $!&! >Rc( $#&! $%&! Mar 8 #'&! #)&! >Rc* Mikey Z Calaveras, The Bryan Sutton, Michael Julian & the Fools Red Clay David Holt & Shay Lage Midlife Crisis Creek Ramblers & T. Michael Black Group eYVdVTcVe ]`TR]c``edeR]V_e S]fVXcRdd Sc`eYVcdWc`^ XV_cVViaR_UZ_X dZ_XZ_Xd`_XhcZeZ_X T`f_ecjc`T\ Coleman :cV]R_U|dW`cV^`de XfZeRcgZcef`d` ]ZgVd`Wd`^V`WeYV eYcVVXcVReXfZeRcZded WR^Z]j`Wd`_X [RkkSVj`_U 3Rj|dSVde TV]VScReVeYV]VXRTj [Rkk^fdZTZR_d -

REVIEWS a L B U M REVIEWS CATS on the COAST - Sea Level - Capricorn CPN0198- LIVE at the BIJOU - Grover Washington Jr

REVIEWS A L B U M REVIEWS CATS ON THE COAST - Sea Level - Capricorn CPN0198- LIVE AT THE BIJOU - Grover Washington Jr. - Kudu KUX Producer: Stewart Levine - List: 7.98 3637 M2 - Producer: Creed Taylor - List: 8.98 The second album from this Macon band consists of eight This two -record set recorded live at Philadelphia's Bijou Cafe songs, four of which are instrumentals. Most of the vocal work is captures the various moods of a Grover Washington concert. handled nicely by Randall Bramblett, but it is on the non -vocal Whether it is the heavily rhythmic "Lock It In The Pocket" to the songs that this band of excellent instrumentalists really takes mellow "You Make Me Dance," Grover's smooth reed work ex- is off. In particular, it is the keyboard work of Chuck Leavell presses just the right feel. The most ambitious cut the 20 - throughout the album that makes it easy to understand why he minute "Days Of Our Lives/Mr. Magic," which starts out slowly, has been named "Best New Keyboardist" in several recent then picks up in tempo, goes free -style for a few bars then year-end polls. launches into the funk of "Mr. Magic." WHEN I NEED YOU - Albert Hammond - Epic JE 35049 - THE FORCE - Kool And The Gang - De -Lite DSR-9501 - Producers: Charlie Calelio and Albert Hammond - List: 7.98 Producers: Ronald Bell and Claydes Smith - List: 7.98 Albert Hammond, who with Carole Bayer Sager wrote the title Another party album from Kool And The Gang, "The Force" songs which Leo Sayer took to number one, has on his latest takes advantage of the current space craze on a number of cuts album 10 songs in the same mainstream pop tradition as the ti- that sound like a funky "Star Wars" soundtrack. -

Import Reviews

Album Picks Import Reviews THIS IS THE MODERN WORLD BEFORE AND AFTER SCIENCE THE JAM-Polydor PD -1-6129 (7.98) BRIAN ENO-Polydor 2302 071 (U.K.) One of the U.K.'s better new wave out- After his recent collaborations with Clus- fits, the group has scored notable success ter, David Bowie and Robert Fripp, Eno there, but has yet to make commercial has finally made the kind of album that gains here. Their second Ip still contains will earn him the recognition he deserves many reference points to the early Who, inhis own right. An impressive cast of but the songs are getting better and the musicians led by PhilCollins are em- inclusionof"All Aroundthe World" ployed to furtherhisproclivities for a makes it a stronger Ip. somewhat offbeat sound. ON FIRE THE DIODES T-CONNECTION-Dash 30008 (TK) (6.98) Columbia PES 90441 (Canada) This sextet specializes in high energy r&b .1.=r MIL Canada's new wave entry was produced and their recent successes speak well for by Bob Gallo who has given the quartet a them. Their percussive sound hits hard powerful but controlled sound and direc- without having to rely on brass to bolster tion. Of note is the group's version of the its impact on songs like the punchy title Cyrkle's "Red Rubber Ball" andBarry tune which moves along at a brisk pace rr Mann -Cynthia Weil's "Shapes Of Things for seven minutes. To Come." In between these isa good deal of energy behind songs like "Time THE VERVE YEARS (1952-54) Damage" and "Behind Those Eyes." CHARLIE PARKER-Verve VE-2-2523 (8.98) The third (and final) volume of Parker's ECHOES OF THE 60's/PHIL SPECTOR Verve recordings finds the saxophonist VARIOUS ARTISTS-Phil Spector 2307 013 (U.K.) working with strings, voices, big band and There have been numerous releases of small groups. -

Harald Szeemann Artist Files

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c86978bx No online items Harald Szeemann artist files Alexis Adkins, Heather Courtney, Judy Chou, Holly Deakyne, Maggie Hughes, B. Karenina Karyadi, Medria Martin, Emmabeth Nanol, Alice Poulalion, Pietro Rigolo, Elena Salza, Laura Schroffel, Lindsey Sommer, Melanie Tran, Sue Tyson, Xiaoda Wang, and Isabella Zuralski. Harald Szeemann artist files 2011.M.30.S2 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Harald Szeemann artist files Date (inclusive): 1836-2010, bulk 1957-2005 Number: 2011.M.30.S2 Creator/Collector: Szeemann, Harald Physical Description: 1400 Linear Feet Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Series II of the Harald Szeemann papers contains artist files on more than 24,000 artists. In addition to fine arts artists, Harald Szeemann created artist files for architects, composers, musicians, film directors, authors and philosphers. The contents of the artist files vary widely from artist to artist, but may include artist statements; artist proposals; biographies; correspondence; exhibition announcements; news clippings; notes; photographs of works of art, exhibitions of the artist; posters; resumes; and original works of art. Due to its size, Series II is described in a separate finding aid. The main finding aid for the Harald Szeemann papers is available here: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/cifa2011m30 Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is primarily in German with some material in Italian, French, English and other languages. -

This Girl for Hire a Gun for Honey Girl on the Loose

PYRAMID BOOKS R-1360 50< HONEY WEST TV's Private Eyeful in the ease of the Crafty Killer m HOMY WEST Don't be fooled by the curves. I could flatten you with judo—or drop you with a .32 slug—as fast and finally as any man. But the curves count, too. • • This time, I'm up to my cleavage In mass murder—a comedian's corpse, a battered beauty, a poisoned pipsqueak— with side dishes of narcotics, adultery, and kidnapping. Not to mention the guy who wanted me to model a transparent bathing suit. Well . it's a living. THE ADVENTURES OF HONEY WEST THIS GIRL FOR HIRE A GUN FOR HONEY GIRL ON THE LOOSE HONEY IN THE FLESH GIRL ON THE PROWL KISS FOR A KILLER DIG A DEAD DOLL BLOOD AND HONEY BOMBSHELL ANGEL FROM HELL (in preparation) wIMS GIRL FOR HIRE G. G. FICKLiNG PYRAMID BOOKS • NEW YORK To Tina and Richard Prather. Ongalabongay! And to Shell Scott who can play house with Honey any old timel THIS GIRL FOR HIRE A PYRAMID BOOK-First printing, July 1957 Second printing, November 1957 Third printing, June 1958 Fourth printing, March 1965 Fifth printing, December 1965 This book is fiction. No resemblance is Intended be- tween any character herein and any person, living or dead; any such resemblance is purely coincidental. © 1957, by Gloria and Forrest E. Fielding All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America PYRAMID BOOKS are published by Pyramid Publications, Inc. 444 Madison Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10022, U.S.A. -

Pompton Lakes DVD Title List

Pompton Lakes DVD Title List Title Call Number MPAA Rating Date Added Release Date 007 A View to A Kill DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 10/2/2012 007 Diamonds are Forever DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 10/2/2012 007 Dr. No BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 For Your Eyes Only BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 9/15/2015 007 From Russia with Love BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2002 007 James Bond: Licence to Kill DVD 007 PG-13 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: On Her Majesty's Secret Service DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Living Daylights DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Pierce Brosnan Collection DVD 007 PG-13 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Roger Moore Collection, vol. 1 DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Roger Moore Collection, vol. 2 DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Sean Connery Collection, vol. 1 DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 Live and Let Die BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 Moonraker BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 On Her Majesty's Secret Service DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 5/16/2000 007 The Man with the Golden Gun BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 The Man with The Golden Gun BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 The Spy Who Loved Me DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 10/2/2012 007 Thunderball BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 12/19/2001 007 You Only Live Twice BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 9/15/2015 10 Secrets for Success and Inner Peace DVD DYE Not Rated 12/2/2011 3/24/2009 Tuesday, August 13, 2019 Page 1 of 220 Title Call Number MPAA Rating Date Added Release Date 10 Things I Hate About You (10th Ann DVD Edition) DVD TEN PG-13