Silver Donald Cameron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

150 Books of Influence Editor: Laura Emery Editor: Cynthia Lelliott Production Assistant: Dana Thomas Graphic Designer: Gwen North

READING NOVA SCOTIA 150 Books of Influence Editor: Laura Emery Editor: Cynthia Lelliott Production Assistant: Dana Thomas Graphic Designer: Gwen North Cover photo and Halifax Central Library exterior: Len Wagg Below (left to right):Truro Library, formerly the Provincial Normal College for Training Teachers, 1878–1961: Norma Johnson-MacGregor Photos of Halifax Central Library interiors: Adam Mørk READING NOVA SCOTIA 150 Books of Influence A province-wide library project of the Nova Scotia Library Association and Nova Scotia’s nine Regional Public Library systems in honour of the 150th anniversary of Confederation. The 150 Books of Influence Project Committee recognizes the support of the Province of Nova Scotia. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Department of Communities, Culture and Heritage to develop and promote our cultural resources for all Nova Scotians. Final publication date November 2017. Books are our finest calling card to the world. The stories they share travel far and wide, and contribute greatly to our global presence. Books have the power to profoundly express the complex and rich cultural life that makes Nova Scotia a place people want to visit, live, work and play. This year, the 150th Anniversary of Confederation provided Public Libraries across the province with a unique opportunity to involve Nova Scotians in a celebration of our literary heritage. The value of public engagement in the 150 Books of Influence project is demonstrated by the astonishing breadth and quality of titles listed within. The booklist showcases the diversity and creativity of authors, both past and present, who have called Nova Scotia home. -

Beaton-Mikmaw.Pdf

4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 2010-800.012.001 Medicine Man's brush. -- [ca. 1860]. -- 1 brush : dyed quills with brass, wire and coconut fibres ; 31 cm. Scope and Content Item is an original brush, believed to be of Mi'kmaw origin. 2011-001.001 Domed Top Quill Box. -- [ca. 1850]. -- 1 box : dyed quills with pine, birchbark, and spruce root binding ; 18 x 19 x 27 cm Scope and Content Item is an original quill box made by Nova Scotia Mi'kmaq. Notes This piece has an early Mi'kmaw winged design (prior to the tourist trade material). 2011-001.002 Round Quill Storage Box. -- [ca. 1870]. -- 1 box : dyed quills with pine, birchbark, and spruce root binding ; 12 x 20 cm Scope and Content Item is an original quill box collected in Cape Breton in the 1930s. 2011-001.003 Oval Box. -- [18--]. -- 1 box : dyed quills with pine, birchbark, and spruce root binding ; 8 x 9 x 14 cm Scope and Content Item is an original quill box featuring an intricate Mi'kmaw design (eagles and turtles). 2011-001.004 Oval Box. -- [between 1925 and 1935]. -- 1 box : dyed quills with pine, birchbark, spruce root, and sweetgrass ; 6 x 8 x 13 cm Scope and Content Item is an original Mi'kmaw quill box. 2011-001.005 Mi'kmaw Oval Panel. -- [ca. 1890s]. -- 1 panel : dyed quills mounted on birchbark ; 18 x 27 cm Scope and Content Item is an original Mi'kmaw quill panel featuring a turtle and eagle design. -

The Artssmarts Story Silver Donald Cameron the Artssmarts Story

The ArtsSmarts Story Silver Donald Cameron The ArtsSmarts Story hen Silver Donald Cameron, one of Canada’s most creative and engaging writers, agreed to document the ArtsSmarts WStory, we could not have been more pleased. The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation developed and is funding ArtsSmarts in order that artists might bring a new way of learning to children in schools and communities across Canada. It took very little time for Donald, through his warm way with children and his keen ability to observe the world and all of its nuances, to understand the magic of creative learning through art as well as the value and potential of “art-infused” education. He shares that magic here. The Canadian Conference of the Arts has been an essential contributor to the development of ArtsSmarts and acts as the National Secretariat for the program. For more information on the CCA, please visit www.ccarts.ca. — The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation Photographs courtesy of ArtsSmarts Partners across Canada. © Canadian Conference of the Arts, October 2001 ISBN 0-920007-44-9 Cover and this page: Mural project in mixed media (detail) by artist Joey Mallet and students at Maple Creek Middle School in Coquitlam, BC. The mural was part of an ArtStarts in Schools project. S ydney Vrana raises his baton. The classroom falls silent. Vrana brings the baton down, and the light, silvery chime of a plucked dulcimer floats on the air. The recorders pick up the melody. The percussion follows: drums, triangle, cymbals and shaken gourds, then xylophone, lute and tambourine. Measured and ethereal, the music evokes a stately dance of robed figures in mid-air: imperturbable, decorous and serene. -

Bibliography of the Margaret Laurence Collection of Books in the Trent University Archives

Bibliography of the Margaret Laurence Collection of Books in the Trent University Archives Note: this is in Library of Congress call number order The tale of the nativity, as told by the Indian children of Inkameep, British Columbia. [Victoria, B.C. : Committee for the Revival and Furtherance of B.C. Indian Arts, 1940?] BT 315.2 .T34 1940 ML Hiebert, Paul, 1892- Not as the scribes / Paul Hiebert. Winnipeg : Queenston House Pub., c1984. BV 4637 .H53 1984 ML Frye, Christine, 1938- Through the darkness : the psalms of a survivor / by Christine Frye ; [with a foreword by Robert A. Raines]. Winfield, B.C. : Wood Lake Books, [1983] BV 4832.2 .F7 1983 ML Staebler, Edna Louise Cress, 1906- Sauerkraut and enterprise. Illustrated by Jean Forden. [Kitchener, Ont.] University Women's Club of Kitchener and Waterloo [1967] BX 8117 .O57 S7 1967 ML McLeod, Bruce. City sermons : preaching from a downtown church / Bruce McLeod ; compiled and edited by Shirley Mann Gibson ; foreword by Gary Lautens. Burlington, Ont. : Welch Pub. Co., c1986. BX 9882 .M332 1986 ML Braithwaite, Max. The night we stole the Mounties car / Max Braithwaite. Rev. ed. Toronto : McClelland & Stewart, 1975, c1969. CT 310 .B6 A3 1975 ML Morris, Audrey Yvonne, 1930- Gentle pioneers : five nineteenth-century Canadians / by Audrey Y. Morris. Don Mills, Ont. : Paperjacks, [1973] CT 310 .S77 M6 1973 ML Chadwick, Nora K. (Nora Kershaw), 1891-1972. The Celts [by] Nora Chadwick. With an introductory chapter by J. X. W. P. Corcoran. [Harmondsworth, Eng.] Penguin Books [1970] D 70 .C47 1970 ML Hiroshima and Nagasaki : the physical, medical, and social effects of the atomic bombings / the Committee for the Compilation of Materials on Damage Caused by the Atomic Bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki ; translated by Eisei Ishikawa and David L. -

Download All Written Submissions for This Bill

V. the green interview .com Work/s 8!gqe:t • The Lsues The VVo:kLs Fnest Mnx/s Remarks to the Law Amendments Committee Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia by Silver Donald Cameron Host and Executive Producer TheGreenlnterview.com April 27, 2015 Good afternoon. Thank you for this opportunity to speak. the green interview .com My name is Silver Donald Cameron, and as many of you will know I’m a self-employed author, broadcaster, internet publisher and ,te Vno s 6.’qqeN:ues filmmaker. ye also been a university dean, I professor and and for Worlds Fhesr M,’nd: 13 years I was a columnist with the Sunday Herald. I’ve been living and working — and voting and sailing and paying taxes — in Nova Scotia full-time since 1971, mostly in rural Nova Scotia. My current venture is called www.TheGreenlnterview.com. It’s a subscription website which also distributes its intellectual products through four US distributors to millions of students, teachers and library patrons all over the world. I am in fact exactly the kind of information- age entrepreneur that governments are always saying they’re eager to encourage. And no wonder. The cultural industries are the fastest, cheapest job-creators in the whole economy. But my remarks today are about net-pen aquaculture. As a spin-off of The Green Interview, my colleagues and I have also produced documentary films. One of these is called Salmon Wars, and some of you are probably familiar with it. It has its own website, www.SaImonWars.com. To be sure you have a chance to view it, I’ve brought a DVD for each of you. -

Beaton Institute

A Brief Guide to the Manuscript Holdings at the Beaton Institute Copyright 2002 by the Beaton Institute Beaton Institute “A Brief Guide to the Manuscript Holdings at the Beaton Institute” All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission of the publisher. Although every effort to ensure the information was correct at time of printing, the publisher does not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for loss or damages by errors or omissions. Beaton Institute Cape Breton University 1250 Grand Lake Road P.O. Box 5300 Sydney, Nova Scotia B1P 6L2 Canada (902) 563-1329 [email protected] http://cbu.uccb.ns.ca WELCOME TO THE BEATON INSTITUTE Preserving Cape Breton’s Documentary Heritage he Beaton Institute welcomes you to discover the resources we have T to assist in your research. We are a research centre and archives mandated to collect and conserve the social, economic, political, and cultural history of Cape Breton Island. It is a centre for local, regional, national and international research and is the official repository for the historically significant records of Cape Breton University. The Beaton aims to promote inquiry through innovative public programming and community-based initiatives. This volume is aimed at people who are conducting research in the manuscript holdings. It contains brief annotations for each manuscript group that can be found at the Beaton Institute. The information compiled in this book should give researchers a clearer idea of what the Beaton holds, and should provide alternative avenues to further your research. -

University of British Columbia Library Special Collections

University of British Columbia Library Special Collections INVENTORY HUBERT EVANS PAPERS Revised and Compiled by DAVID RANSON Produced by CENTRE FOR TEXTUAL STUDIES Department of English UBC TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Scope and Content iii Biographical Note iv Part I: First Accession of Hubert Evans’s Papers 1 Part II: Second accession of Hubert Evans’s Papers 13 Part III: Papers of Anna Winter Evans 33 Part IV: Video and Audio Materials 40 —U— INTRODUCTION: SCOPE AND CONTENT The papers ofHubert Evans span Ca. 1920—1985, although the majority of material falls between the years Ca. 1940—1985. The first and second parts of the collection include in manuscript and published form many of Evans’s articles, short stories, radio plays, poems, and novels, including Mist on the River and 0 Time in Your Flight. Parts one and two also contain many of Evans’s diaries, journals, notebooks, sketchbooks, and quotation collections which provide valuable insights into the author’s personality. His extensive business and personal correspondence includes letters to and from Margaret Laurence, Silver Donald Cameron, and Grace Maclnnis, as well as many readers and publishing houses. There is also information on a segment of Evans’s genealogy and a number of items relating to the awarding of his honourary degree from Simon Fraser University in 1984. The third part of the collection consists of the papers of Hubert Evans’s wife, Ann (Anna) Winter Evans. While there is only a small amount of personal and business correspondence in this part of the collection, there are a large number of typescripts and publications of Ann Evans’s numerous stories and articles. -

Dalhousiegazette Volume109 Fe

~ - ~ ~.., tlant1c~lssue Volume J Number J Feb.-Apr. 1977 free Atlantic development Have ~e been had! by Ralph Surette abortive attempt to raise cattle on the barrens of the prtmary resorces of farming and the fishery. For those who had the misfortune to believe Newfoundland, one might have been tempted to In some ways this is an unspoken admission of that what we have been doing in the Atlantic accept this argument. Surely, more industrial the failure of industrial development. It should Provinces for the last quarter of a century to intelligence and evaluation capacity is needed. have been done before, not after, billions of attract industry constitutes "progress," the But after the continual refusal to learn from dollars went down· the pipe on hare-brained winter of 1977 has come as a shock. experience which is exhibited by the New schemes. Twenty-five years and billions of dollars later Brunswick government even now, what hope is Strengthening the farming and fishery we have an unemployment rate that varies between 10 and SO per cent in some areas and localities. The industrial roulette wheel has come full circle, and Shaheen, Spevack, Bricklin, Doyle and their like haven't saved us after all. That things have come to a sorry pass was evident early, as some of the gurus of industrialization East-coast style started chew ing each other out back in December. Robert Stanfield said the DREE didn't know where it was going any more, Tom Kent complained that the "bi'g bang" theory of economic development of the 1960's with its spectacular failures had contributed to Cape Breton's present sorry plight, and Robert Manuge, an early president of Nova Scotia's Industrial Estates Ltd., complained about Tom Kent. -

Office of the Prime Minister 80 Wellington Street Ottawa, on K1A 0A2

Office of the Prime Minister 80 Wellington Street Ottawa, ON K1A 0A2 February 17, 2015 Dear Prime Minister Harper: As business leaders, commercial and recreational fishing associations, scientists, lawyers and environmentalists who care deeply about sustainable jobs, prosperous coastal communities and healthy ecosystems, we are gravely concerned about the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ proposal to, in essence, exempt the aquaculture industry from the Fisheries Act provisions that prohibit the release of deleterious substances into water frequented by fish. We believe the proposed changes, if enacted, will lead to the discharge of increasingly powerful pesticides and other potentially damaging substances into the ecosystem, significantly reduce government regulatory oversight, and damage Canada’s commercial interests as a provider of untainted seafood. Needless to say, these factors diminish our international reputation for environmental protection. The Fisheries Act has been a mainstay of environmental protection for more than 100 years and the section dealing with deleterious substances is key to ensuring that those of us who use Canada’s aquatic ecosystems, be they marine or freshwater, do so in an environmentally sound and responsible manner. This section of the Act has never been used inappropriately or frivolously. It has however been used to stop activities highly damaging to fish and their habitat. The most recent instance involved an aquaculture operator in New Brunswick who pled guilty to violating the Fisheries Act, in illegally using a pesticide at 15 aquaculture sites, over an extended period of time and despite warnings from Environment Canada. The pesticide is known to be toxic to lobsters and was likely the cause of mortality in hundreds of lobsters found dead in lobster traps during the period of illegal use. -

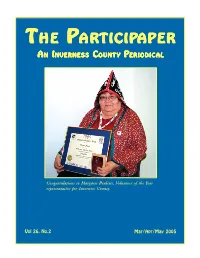

2005 Issue 2 the Participaper

TTHEHE PPARARTICIPTICIPAPERAPER AN INVERNESS COUNTY PERIODICAL Congratulations to Margaret Poulette, Volunteer of the Year representative for Inverness County. Vol 26, No.2 Mar/Apr/May 2005 Page 1 The Participaper FROM THE DIRECTOR’S DESK The Participaper INVERNESS COUNTY RECREATION, TOURISM, Editor, Graphic Design and Production Marie Aucoin CULTURE AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT OFFICE PO Box 43, Cheticamp, NS, B0E 1H0 VOLUNTEER RECOGNITION: Phone: (902) 224-1759 email: [email protected] This year the Municipality received 50 (for subscription requests see below) nominations from organizations The Participaper is published five times a year by the throughout the County wishing to honour Inverness County Department of Recreation and Tourism: John Cotton, Director. Contributions of information and their hard working volunteers. articles, photos and artwork are welcome. We also welcome Congratulations to all! See inside this issue for the your letters and comments. This publication is a service for volunteer’s biographies and photos. the residents of Inverness County. Others may subscribe at the following rates (postage included): $8.00/yr in Canada SENIOR GAMES: or $9:00/yr in the US. Send subscription request, with payment, to the attention of: On Saturday June 4, the 2005 Senior Games will take Marie Cameron Recreation and Tourism Department place at the Inverness Academy in Inverness. The games PO Box 179, Municipal Building are open to all county residents 50 years+. Activities Port Hood, NS, B0E 2W0 include some friendly competition, with team events Email: [email protected] such as horseshoes, scrabble, cards and darts. There Copyright 8 2005 will also be entertainment, socializing, informative All rights reserved. -

THE FIRST HUNDRED-ODD INTERVIEWS (And Six Documentary Films)

THE FIRST HUNDRED-ODD INTERVIEWS (and six documentary films) August 18, 2019 The interviews were released and have been posted on the site in this order, beginning in 2009. James Lovelock, the originator of the Gaia theory, which holds that the Earth behaves like a single living organism. Lovelock's importance to science has been compared to that of Darwin. Paul Watson, hero of the TV series Whale Wars, and head of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, the most powerful organization in the world in defense of whales, seals and sea life. Vandana Shiva, physicist, philosopher, environmental actvist, eco-feminist, and author of numerous books on subjects like Biopiracy and Earth Democracy. Fariey Mowat, legendary environmental writer and activist, author of more than 40 books, including the bleak masterpiece, Sea of Slaughter. Elizabeth May, author of eight books, lifelong environmental activist, long-time Executive Director of the Sierra Club of Canada, and latterly the Leader of the Green Party of Canada. David Hughes, a retired Canadian government geologist and Fellow of the Post-Carbon Institute whose research describes a disruptive new era of oil scarcity and high-cost energy. Jeff Rubin, former Chief Economist with CIBC World Markets and author of Why Your World is About to Get a Whole Lot Smaller, which explores the probable impact of dramatically higher oil prices. Satish Kumar, a leader of the UK’s spirituality and ecology movements for more than three decades, and editor of Resurgence magazine. Gwynne Dyer, perhaps the world's best-known and most distinguished expert on war, and author of the recent book Climate Wars. -

Download Download

Book Reviews Seasons in the Rain, by Silver Donald Cameron. McClelland & Stewart, 1978. Paper, $6.95. I remember Donald Cameron (the Silver has been a later adornment) as a young UBC academic who astonished me when I was editing Cana dian Literature by submitting an essay which actually found something new to say about Stephen Leacock. I accepted it and — as Cameron remarks in Seasons in the Rain — started him on what has become a professional writing career. More than a decade ago Cameron departed from academia and since then he has worked freelance as one of the brighter and more urbane writers in popular magazines like Weekend and Saturday Night. Seasons in the Rain is a collection of pieces that mostly appeared first in such journals and which have been minimally polished to fit them into a cohesive volume. Normally such collections are not very interesting, since the writing in popular magazines is looser and the attention is nearer the surface than one expects in a book. What relaxes one's mind on a plane or after Sunday lunch is not usually durable enough to take a second and more serious reading. But Seasons in the Rain does hold one's attention, and I think there are two reasons for it. One is the unity of the book, which consists of a series of pieces written around a series of returns to the British Columbian haunts of Cameron's childhood and youth. Born "accidentally" in On tario, Cameron regarded himself as to all intents and purposes a Van- couverite, which "means I think of mountains as friendly, and I will never be at home away from the sea." But he is a self-exiled British Columbian, for in 1964 he departed and he has not returned except as a visitor.