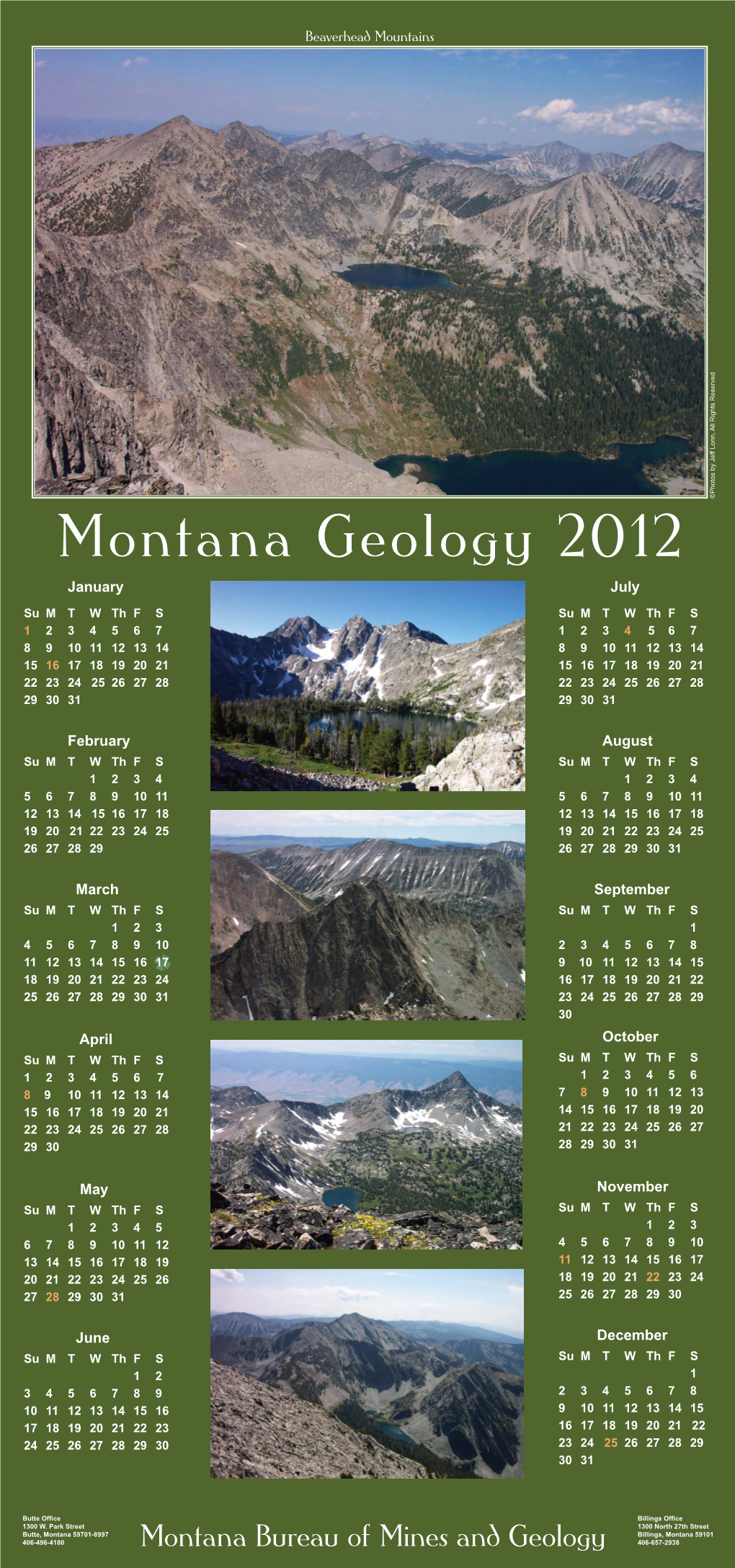

Beaverhead Range Beaverhead Mountains Became Part of the Boundary Are Part of an Immensely Thick Sequence of 1.4 Billion-Year-Old (Middle Between the Two Territories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characteristics and Estimates of Visitors to Montana's Historic Virginia and Nevada Cities

Characteristics and Estimates of Visitors to Montana's Historic Virginia and Nevada Cities Research Report 73 February 2000 Characteristics and Estimates of Visitors to Montana's Historic Virginia and Nevada Cities Prepared by Kim McMahon Norma P. Nickerson, Ph.D. Research Report 73 February 2000 Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research School of Forestry The University of Montana Missoula, MT www.forestry.umt.edu/itrr Funded by the Lodging Facility Use Tax The Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research School of Forestry The University of Montana Missoula, MT 59812 (406) 243-5686 www.forestry.umt.edu/itrr Title of Report: Characteristics and Estimates of Visitors to Montana's Historic Virginia and Nevada Cities Report Number: Research Report 73 Authors: Kim McMahon, Norma Nickerson Month Published: February 2000 Executive Summary Introduction Visitors to Virginia and Nevada City were divided into two groups: Montana Visitors : visitors from Montana who have a residence besides Virginia City, Nevada City, or Sheridan, Montana. Out-of-State Visitors : visitors with residence outside of Montana. Methodology Traffic counters and traffic intercepts were used to establish total traffic through Virginia and Nevada City from July 1 through September 30, 1999. Traffic intercepts occurred during three four-day intervals throughout the study period in order to describe the population of vehicles that passed over the traffic counters. Privately-owned vehicles were pulled off the roadway for a brief interview regarding current place of residence, number of adults and youth in the travel group, length of time spent in Virginia and Nevada City, and rental vehicles. In all, 11,696 vehicles were counted during the 12 intercept days. -

Historic Settlement of the Rattlesnake Creek Drainage, Montana| an Archaeological and Historical Perspective

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2005 Historic settlement of the Rattlesnake Creek Drainage, Montana| An archaeological and historical perspective Daniel S. Comer The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Comer, Daniel S., "Historic settlement of the Rattlesnake Creek Drainage, Montana| An archaeological and historical perspective" (2005). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2544. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2544 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 80-190, 271-289 This reproduction is the best copy available. dfti UMI Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of IVIontdn^ Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entiret>', provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, 1 do not grant permission Author's Signature: J. i-O frJir^ Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or fmancial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. -

MBMG 505-Jefferson-V2.FH10

GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE CENOZOIC DEPOSITS OF THE UPPER JEFFERSON VALLEY MBMG Open File Report 505 2004 Compiled and mapped by Susan M. Vuke, Walter W. Coppinger, and Bruce E. Cox This report has been reviewed for conformity with Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology’s technical and editorial standards. Partial support has been provided by the STATEMAP component of the National Cooperative Geology Mapping Program of the U.S. Geological Survey under contract Number 03HQAG0090. CENOZOIC DEPOSITS OF THE UPPER JEFFERSON VALLEY Cenozoic deposits are the focus of the Geologic Map of the upper Jefferson Valley. The map is largely a compilation of previous mapping with additional interpretations based on aerial photos and limited additional field work. Older rocks are included to show their relations to the Cenozoic deposits, but they are generalized on the map. Lithologic descriptions of the Cenozoic deposits are given in the map explanation (p. 17). References used for the map compilation are shown on p. 15. The northern and southern parts of the map are discussed separately. NORTHERN PART OF MAP AREA Quaternary deposits A variety of Quaternary deposits blanket much of the slope area of the Whitetail and Pipestone Creek valleys between the flanks of the Highland Mountains and Bull Mountain (Fig. 1). East and southeast of these Quaternary slope deposits are more isolated areas of partly cemented Pleistocene gravels on pediments. One of these gravel deposits near Red Hill (Fig. 1) yielded a late Pleistocene vertebrate assemblage including cheetah, horse, camel, and large mountain sheep. Radiocarbon dates from the lowest part of the sequence range between 10,000 and 9,000 14C yr. -

A HISTORY OP FORT SHAW, MONTANA, from 1867 to 1892. by ANNE M. DIEKHANS SUBMITTED in PARTIAL FULFILLMENT of "CUM LAUDE"

A HISTORY OP FORT SHAW, MONTANA, FROM 1867 TO 1892. by ANNE M. DIEKHANS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF "CUM LAUDE" RECOGNITION to the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CARROLL COLLEGE 1959 CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRARY HELENA, MONTANA MONTANA COLLECTION CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRAS/- &-I THIS THESIS FOR "CUM LAUDE RECOGNITION BY ANNE M. DIEKHANS HAS BEEN APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY Date ii PREFACE Fort Shaw existed as a military post between the years of 1867 and 1892. The purpose of this thesis is to present the history of the post in its military aspects during that period. Other aspects are included but the emphasis is on the function of Fort Shaw as district headquarters of the United States Army in Montana Territory. I would like to thank all those who assisted me in any way in the writing of this thesis. I especially want to thank Miss Virginia Walton of the Montana Historical Society and the Rev. John McCarthy of the Carroll faculty for their aid and advice in the writing of this thesis. For techni cal advice I am indebted to Sister Mary Ambrosia of the Eng lish department at Carroll College. I also wish to thank the Rev. James R. White# Mr. Thomas A. Clinch, and Mr. Rich ard Duffy who assisted with advice and pictures. Thank you is also in order to Mrs. Shirley Coggeshall of Helena who typed the manuscript. A.M.D. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chggter Page I. GENERAL BACKGROUND............................... 1 II. MILITARY ACTIVITIES............................. 14 Baker Massacre Sioux Campaign The Big Hole Policing Duties Escort and Patrol Duties III. -

BIG HOLE National Battlefield

BIG HOLE National Battlefield Historical Research Management Plan & Bibliography of the ERCE WAR, 1877 F 737 .B48H35 November 1967 Historical Research Management Plan BIG HOLE NATI ONAL for .BATILEFIELD LI BRP..RY BIG HOLE Na tional Battlefield & Bibliog raphy of the N E Z PERCE WAR, 1877 By AUBREY L. HAINES DIVISION OF HISTORY Office of Archeology and Historic Preservatio.n November 1967 U.S. Department of the Interior NATI ONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL RESEARCH MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR BIG HOLE NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD November 1968 Recommended Superintendent Date Reviewed Division of History Date Approved Chief, Office of Archeology Date and Historic Preservation i TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Research Management Plan Approval Sheet I. The Park Story and Purpose . • • • 1 A. The Main His torical Theme ••••••• 1 B. Sub sidiary Historical Theme • • • • • 1 1 c. Relationship of Historical Themes to Natural History and Anthropology • • • • • • • • 12 D. Statement of Historical Significance •• 14 E. Reasons for Establishment of the Park • • • • • 15 II. Historical Resources of the Battlefield 1 7 A. Tangible Resources • • • • 17 1. Sites and Remains 1 7 a. Those Related to the Main Park Theme • • . 1 7 b. Those Related to Subsidiary Themes • 25 2. Historic Structures 27 B. Intangible Resources • 2 7 c. Other Resources 2 8 III.Status of Research •• 2 9 A. Research Accomplished 29 H. Research in Progress • • • • • 3o c. Cooperation with Non-Service Institutions 36 IV. Research Needs ••••••••••••••••• 37 A. Site Identification and Evaluation Studies 37 H. General Background Studies and Survey Histories 40 c. Studies for Interpretive Development • • • • • 4 1 D. Development Studies • • • • • • • • • 4 1 E. -

Edings of The

Proceedings of the FIRE HISTORYIISTORY WORKSHOP October 20-24, 1980 Tucson, Arizona General Technical Report RM.81 Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Forest Service U.S. Department of Agriculture Dedication The attendees of The Fire History Workshop wish to dedicate these proceedings to Mr. Harold Weaver in recognition of his early work in applying the science of dendrochronology in the determination of forest fire histories; for his pioneering leadership in the use of prescribed fire in ponderosa pine management; and for his continued interest in the effects of fire on various ecosystems. Stokes, Marvin A., and John H. Dieterich, tech. coord. 1980. Proceedings of the fire history workshop. October 20-24, 1980, Tucson, Arizona. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-81, 142 p. Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, Cob. The purpose of the workshop was to exchange information on sampling procedures, research methodologies, preparation and interpretation of specimen material, terminology, and the appli- cation and significance of findings, emphasizing the relationship of dendrochronology procedures to fire history interpretations. Proceedings of the FIRE HISTORY WORKSHOP October 20.24, 1980 Tucson, Arizona Marvin A. Stokes and John H. Dieterich Technical Coordinators Sponsored By: Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture and Laboratory of Tree.Ring Research University of Arizona General Technical Report RM-81 Forest Service Rocky Mountain Forest and Range U.S. Department of Agriculture Experiment Station Fort Collins, Colorado Foreword the Fire has played a role in shaping many of the the process of identifying and describing plant communities found in the world today. -

The Boulder River Watershed Study, Jefferson County, Montana

The Boulder River Watershed Study, Jefferson County, Montana By Stanley E. Church, David A. Nimick, Susan E. Finger, and J. Michael O’Neill Chapter B of Integrated Investigations of Environmental Effects of Historical Mining in the Basin and Boulder Mining Districts, Boulder River Watershed, Jefferson County, Montana Edited by David A. Nimick, Stanley E. Church, and Susan E. Finger Professional Paper 1652–B U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 15 Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................................................... 17 Description of Study Area ......................................................................................................................... 17 Hydrologic Setting ............................................................................................................................. 17 Biologic Setting .................................................................................................................................. 19 Geologic Setting................................................................................................................................. 20 Mining History .................................................................................................................................... 20 Remediation Activities -

WORK PLAN BEAVERHEAD RIVER WATERSHED UPDATED: January 2009

WORK PLAN BEAVERHEAD RIVER WATERSHED UPDATED: January 2009 INTRODUCTION PURPOSE The purpose for this watershed plan is to: (1) Identify and document resource concerns within the watershed, both water and non- water related. (2) Prioritize those concerns (3) Outline objectives and methods of addressing those concerns (4) Provide guidance in the implementation of action plans and other associated watershed activities. This document will be maintained as a guide for watershed activities, and will be updated annually to reflect current circumstances in the watershed including reprioritization of concerns and addition of new areas of concentration. BEAVERHEAD RIVER WATERSHED COMMITTEE – MISSION STATEMENT The mission of the Beaverhead Watershed Committee is to seek an understanding of the watershed – how it functions and supports the human communities dependent upon it – and to build agreement on watershed-related planning issues among stakeholders with diverse viewpoints. Goals: . Provide a mechanism and forum for landowners, citizens, and agencies to work together to: . Identify problems and concerns both riparian and non-riparian, urban and rural. Reach agreement upon the priority of and methods for addressing those concerns. Act as a conduit between local interests and agencies for purposes of procuring the funding and non-monetary assistance necessary to begin systematically addressing priority concerns. Foster a cooperative environment where conflict is avoided, and work to resolve conflict as necessary for the watershed effort to move forward. Stay abreast of opportunities, issues, and developments that could be either beneficial or detrimental to the watershed or segments of the watershed. Keep stakeholders appropriately informed. Objectives: . Continuous Improvement – Maintain a broad range of active improvement projects/programs relating to diverse attributes of the watershed. -

Lewis & Clark Timeline

LEWIS & CLARK TIMELINE The following time line provides an overview of the incredible journey of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Beginning with preparations for the journey in 1803, it highlights the Expedition’s exploration of the west and concludes with its return to St. Louis in 1806. For a more detailed time line, please see www.monticello.org and follow the Lewis & Clark links. 1803 JANUARY 18, 1803 JULY 6, 1803 President Thomas Jefferson sends a secret letter to Lewis stops in Harpers Ferry (in present-day West Virginia) Congress asking for $2,500 to finance an expedition to and purchases supplies and equipment. explore the Missouri River. The funding is approved JULY–AUGUST, 1803 February 28. Lewis spends over a month in Pittsburgh overseeing APRIL–MAY, 1803 construction of a 55-foot keelboat. He and 11 men head Meriwether Lewis is sent to Philadelphia to be tutored down the Ohio River on August 31. by some of the nation’s leading scientists (including OCTOBER 14, 1803 Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Smith Barton, Robert Patterson, and Caspar Wistar). He also purchases supplies that will Lewis arrives at Clarksville, across the Ohio River from be needed on the journey. present-day Louisville, Kentucky, and soon meets up with William Clark. Clark’s African-American slave York JULY 4, 1803 and nine men from Kentucky are added to the party. The United States’s purchase of the 820,000-square mile DECEMBER 8–9, 1803 Louisiana territory from France for $15 million is announced. Lewis leaves Washington the next day. Lewis and Clark arrive in St. -

The Ethnography of On-Site Interpretation and Commemoration

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2013 The Ethnography of On-Site Interpretation and Commemoration Practices: Place-Based Cultural Heritages at the Bear Paw, Big Hole, Little Bighorn, and Rosebud Battlefields Helen Alexandra Keremedjiev The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Keremedjiev, Helen Alexandra, "The Ethnography of On-Site Interpretation and Commemoration Practices: Place-Based Cultural Heritages at the Bear Paw, Big Hole, Little Bighorn, and Rosebud Battlefields" (2013). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1009. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1009 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETHNOGRAPHY OF ON-SITE INTERPRETATION AND COMMEMORATION PRACTICES: PLACE-BASED CULTURAL HERITAGES AT THE BEAR PAW, BIG HOLE, LITTLE BIGHORN, AND ROSEBUD BATTLEFIELDS By HELEN ALEXANDRA KEREMEDJIEV Master of Arts, The University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, 2004 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment -

Idaho: Lewis Clark Byway Guide.Pdf

The Lewis and Clark Backcountry Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho Meriwether Lewis’s journal entry on August 18, 1805 —American Philosophical Society The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway and Adventure Road is a 36 mile loop drive through a beautiful and historic landscape on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail. The mountains, evergreen forests, high desert canyons, and grassy foothills look much the same today as when the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through in 1805. THE PUBLIC LANDS CENTER Salmon-Challis National Forest and BLM Salmon Field Office 1206 S. Challis Street / Salmon, ID 83467 / (208)756-5400 BLM/ID/GI-15/006+1220 Getting There The portal to the Byway is Tendoy, Idaho, which is nineteen miles south of Salmon on Idaho Highway 28. From Montana, exit from I-15 at Clark Canyon Reservoir south of Dillon onto Montana Highway 324. Drive west past Grant to an intersection at the Shoshone Ridge Overlook. If you’re pulling a trailer or driving an RV with a passenger vehicle in tow, it would be a good idea to leave your trailer or RV at the overlook, which has plenty of parking, a vault toilet, and interpretive signs. Travel road 3909 west 12 miles to Lemhi Pass. Please respect private property along the road and obey posted speed signs. Salmon, Idaho, and Dillon, Montana, are full- service communities. Limited services are available in Tendoy, Lemhi, and Leadore, Idaho and Grant, Montana. -

View the 2015 Summer B.O.D. Meeting Minutes

“On the Trail” NPTF Photo The Quarterly Newsletter of the Nez Perce Trail Foundation • Ocial Partner of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail • Ta’yam (Summer) 2015 President’s Message Dear fellow Nez Perce Trail Foundation members, With the end of summer, it might be a good time to begin planning for 2016. As we look back, the Nez Perce Trail Foundation has experienced a tremendous amount of success relative to our re-organization efforts. The down side of 2015 was that actual “on the trail” improvements and upkeep was at a stand still for several reasons. The worst thing that could happen to the Nez Perce Trail did happen. The fire season of 2015 will not be forgotten for years to come. We have witnessed some of the most disastrous fires throughout the Northwest this year, and the Forest Service resources have been stretched beyond reasonable expectations. The financial strain that has been placed on the U.S. Forest Service will inevitably mean that services, programs, and facilities will be lost or cut back severely. Jim Zimmerman, The USFS is forced to utilize their own budget to combat these annual fires. That is much different than how other President NPTF natural disasters are financially dealt with such as hurricanes, earthquakes, tornados, or floods. Those disasters are funded by way of a completely different procedure and revenue source, and in most cases, involve FEMA. I have personally lobbied House and Senate members to consider funding fire disasters through a separate line item account so that the Forest Service can continue to provide the services and management of our resources as intended.