Diversity of Butterflies in Four Different Forest Types in Mount Slamet, Central Java, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) Q ⇑ Marianne Espeland A,B, , Jason P.W

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 93 (2015) 296–306 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Ancient Neotropical origin and recent recolonisation: Phylogeny, biogeography and diversification of the Riodinidae (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) q ⇑ Marianne Espeland a,b, , Jason P.W. Hall c, Philip J. DeVries d, David C. Lees e, Mark Cornwall a, Yu-Feng Hsu f, Li-Wei Wu g, Dana L. Campbell a,h, Gerard Talavera a,i,j, Roger Vila i, Shayla Salzman a, Sophie Ruehr k, David J. Lohman l, Naomi E. Pierce a a Museum of Comparative Zoology and Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA b McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Powell Hall, 2315 Hull Road, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA c Department of Systematic Biology-Entomology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-127, USA d Department of Biological Sciences, University of New Orleans, 2000 Lake Shore Drive, New Orleans, LA 70148, USA e Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK f Department of Life Science, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan g The Experimental Forest, College of Bio-Resources and Agriculture, National Taiwan University, Nantou, Taiwan h Division of Biological Sciences, School of Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics, University of Washington Bothell, Box 358500, 18115 Campus Way NE, Bothell, WA 98011-8246, USA i Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (CSIC-UPF), Pg. Marítim de la Barceloneta 37, 08003 Barcelona, Spain j Faculty of Biology & Soil Science, St. -

Butterflies-Of-Thailand-Checklist-2018

PAPILIONIDAE Parnassinae: Bhutanitis lidderdalii ocellatomaculata Great Bhutan ผเี สอื้ ภฐู าน Papilioninae: Troides helena cerberus Common Birdwing ผเี สอื้ ถงุ ทองป่ าสงู Troides aeacus aeacus Golden Birdwing ผเี สอื้ ถงุ ทองธรรมดา Troides aeacus malaiianus Troides amphrysus ruficollis Malayan Birdwing ผเี สอื้ ถงุ ทองปักษ์ใต ้ Troides cuneifera paeninsulae Mountain Birdwing ผเี สอื้ ถงุ ทองภเู ขา Atrophaneura sycorax egertoni Whitehead Batwing ผเี สอื้ คา้ งคาวหวั ขาว Atrophaneura varuna zaleucus Burmese Batwing ผเี สอื้ ปีกคา้ งคาวพมา่ Atrophaneura varuna varuna Malayan Batwing ผเี สอื้ ปีกคา้ งคาวมาเลย์ Atrophaneura varuna astorion Common Batwing ผเี สอื้ ปีกคา้ งคาวธรรมดา Atrophaneura aidoneus Striped Batwing ผเี สอื้ ปีกคา้ งคาวขา้ งแถบ Byasa dasarada barata Great Windmill ผเี สอื้ หางตมุ ้ ใหญ่ Byasa polyeuctes polyeuctes Common Windmill ผเี สอื้ หางตมุ ้ ธรรมดา Byasa crassipes Small Black Windmill ผเี สอื้ หางตมุ ้ เล็กด า Byasa adamsoni adamsoni Adamson's Rose ผเี สอื้ หางตมุ ้ อดัมสนั Byasa adamsoni takakoae Losaria coon doubledayi Common Clubtail ผเี สอื้ หางตมุ ้ หางกวิ่ Losaria neptunus neptunus Yellow-bodied Clubtail ผเี สอื้ หางตมุ ้ กน้ เหลอื ง Losaria neptunus manasukkiti Pachliopta aristolochiae goniopeltis Common Rose ผเี สอื้ หางตมุ ้ จดุ ชมพู Pachliopta aristolochiae asteris Papilio demoleus malayanus Lime Butterfly ผเี สอื้ หนอนมะนาว Papilio demolion demolion Banded Swallowtail ผเี สอื้ หางตงิ่ สะพายขาว Papilio noblei Noble's Helen ผเี สอื้ หางตงิ่ โนเบลิ้ Papilio castor mahadeva Siamese Raven ผเี สอื้ เชงิ ลายมหาเทพสยาม -

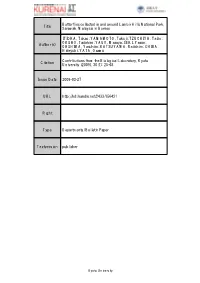

Title Butterflies Collected in and Around Lambir Hills National Park

Butterflies collected in and around Lambir Hills National Park, Title Sarawak, Malaysia in Borneo ITIOKA, Takao; YAMAMOTO, Takuji; TZUCHIYA, Taizo; OKUBO, Tadahiro; YAGO, Masaya; SEKI, Yasuo; Author(s) OHSHIMA, Yasuhiro; KATSUYAMA, Raiichiro; CHIBA, Hideyuki; YATA, Osamu Contributions from the Biological Laboratory, Kyoto Citation University (2009), 30(1): 25-68 Issue Date 2009-03-27 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/156421 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Contn bioL Lab, Kyoto Univ., Vot. 30, pp. 25-68 March 2009 Butterflies collected in and around Lambir Hills National ParK SarawaK Malaysia in Borneo Takao ITioKA, Takuji YAMAMo'rD, Taizo TzucHiyA, Tadahiro OKuBo, Masaya YAGo, Yasuo SEKi, Yasuhiro OHsHIMA, Raiichiro KATsuyAMA, Hideyuki CHiBA and Osamu YATA ABSTRACT Data ofbutterflies collected in Lambir Hills National Patk, Sarawak, Malaysia in Borneo, and in ks surrounding areas since 1996 are presented. In addition, the data ofobservation for several species wimessed but not caught are also presented. In tota1, 347 butterfly species are listed with biological information (habitat etc.) when available. KEY WORDS Lepidoptera! inventory1 tropical rainforesti species diversity1 species richness! insect fauna Introduction The primary lowland forests in the Southeast Asian (SEA) tropics are characterized by the extremely species-rich biodiversity (Whitmore 1998). Arthropod assemblages comprise the main part of the biodiversity in tropical rainforests (Erwin 1982, Wilson 1992). Many inventory studies have been done focusing on various arthropod taxa to reveal the species-richness of arthropod assemblages in SEA tropical rainforests (e.g. Holloway & lntachat 2003). The butterfly is one of the most studied taxonomic groups in arthropods in the SEA region; the accumulated information on the taxonomy and geographic distribution were organized by Tsukada & Nishiyama (1980), Yata & Morishita (1981), Aoki et al. -

(Lepidoptera: Insecta) from Jammu and Kashmir Himalaya

Rec. zool. Surv. India: Vol 119(4)/ 463-473, 2019 ISSN (Online) : 2581-8686 DOI: 10.26515/rzsi/v119/i4/2019/144197 ISSN (Print) : 0375-1511 New records of butterflies (Lepidoptera: Insecta) from Jammu and Kashmir Himalaya Taslima Sheikh and Sajad H. Parey* Baba Ghulam Shah Badshah University, Rajouri – 185234, Jammu and Kashmir, India; [email protected] Abstract Himalayas represents one of the unique ecosystems in terms of species diversity and species richness. While studying taxa of butterflies in Jammu and Rajouri districts located in Western Himalaya, fourteen species (Abisara bifasciata Moore, Pareronia hippia Fabricius, Elymnias hypermnestra Linnaeus, Acraea terpsicore Linnaeus, Charaxes solon Fabricius, Symphaedra nais Forster, Neptis jumbah Moore, Moduza procris Cramer, Athyma cama Moore, Tajuria jehana Moore, Arhopala amantes Hewitson, Jamides celeno Cramer, Everes lacturnus Godart and Udaspes folus Cramer) are recorded for the first time from the Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Investigations for butterflies were carried by following visual encounter method between 2014 and 2019 in morning hours from 7 am to 11 am throughout breeding seasons in Jammu and Rajouri districts. This communication deals with peculiar taxonomical identity, common name, global distribution, IUCN status and photographs of newly recorded butterflies. Keywords: Butterflies, Himalayas, New Record, Species, Jammu & Kashmir Introduction India are 1,439 (Evans, 1932; Kunte, 2018) from oasis, high mountains, highlands, tropical to alpine forests, Butterflies (Class: INSECTA Linnaeus, 1758, Order: swamplands, plains, grasslands, and areas surrounding LEPIDOPTERA Linnaeus, 1758) are holometabolous rivers. group of living organism as they complete metamorphosis cycles in four stages, viz. egg or embryo, larva or Jammu and Kashmir known as ‘Terrestrial Paradise caterpillar, pupa or chrysalis and imago or adult (Gullan on Earth’ categorized to as a part of the Indian Himalayan and Cranston, 2004; Capinera, 2008). -

9 2013, No.1136

2013, No.1136 8 LAMPIRAN I PERATURAN MENTERI PERDAGANGAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 50/M-DAG/PER/9/2013 TENTANG KETENTUAN EKSPOR TUMBUHAN ALAM DAN SATWA LIAR YANG TIDAK DILINDUNGI UNDANG-UNDANG DAN TERMASUK DALAM DAFTAR CITES JENIS TUMBUHAN ALAM DAN SATWA LIAR YANG TIDAK DILINDUNGI UNDANG-UNDANG DAN TERMASUK DALAM DAFTAR CITES No. Pos Tarif/HS Uraian Barang Appendix I. Binatang Hidup Lainnya. - Binatang Menyusui (Mamalia) ex. 0106.11.00.00 Primata dari jenis : - Macaca fascicularis - Macaca nemestrina ex. 0106.19.00.00 Binatang menyusui lain-lain dari jenis: - Pteropus alecto - Pteropus vampyrus ex. 0106.20.00.00 Binatang melata (termasuk ular dan penyu) dari jenis: · Ular (Snakes) - Apodora papuana / Liasis olivaceus papuanus - Candoia aspera - Candoia carinata - Leiopython albertisi - Liasis fuscus - Liasis macklotti macklotti - Morelia amethistina - Morelia boeleni - Morelia spilota variegata - Naja sputatrix - Ophiophagus hannah - Ptyas mucosus - Python curtus - Python brongersmai - Python breitensteini - Python reticulates www.djpp.kemenkumham.go.id 9 2013, No.1136 No. Pos Tarif/HS Uraian Barang · Biawak (Monitors) - Varanus beccari - Varanus doreanus - Varanus dumerili - Varanus jobiensis - Varanus rudicollis - Varanus salvadori - Varanus salvator · Kura-Kura (Turtles) - Amyda cartilaginea - Calllagur borneoensis - Carettochelys insculpta - Chelodina mccordi - Cuora amboinensis - Heosemys spinosa - Indotestudo forsteni - Leucocephalon (Geoemyda) yuwonoi - Malayemys subtrijuga - Manouria emys - Notochelys platynota - Pelochelys bibroni -

Rubber Agroforestry in Thailand Provides Some Biodiversity Benefits Without Reducing Yields

Rubber agroforestry in Thailand provides some biodiversity benefits without reducing yields Supplementary Information This supplementary information includes (text, figures, then tables, in sequence as referred to in main text): Figure S1 Rubber plantation area globally, and in Southeast Asia, 1980 to 2016. Figure S2 Map of study region showing location of farms in the yield dataset within Phatthalung province, and sampling blocks in the biodiversity dataset in Phatthalung and Songkhla provinces. Letters A – E indicate “districts” that identify spatially clumped sampling blocks. Figure S3 Monthly rainfall (sum of daily records) and maximum daily temperatures recorded at Hat Yai airport, Songkhla province, Thailand. Figure S4 Correlation matrix of habitat structural variables across all plots using Pearson correlation, showing a) all variables and b) selected summarised variables Figure S5 Validation of point-based land-use quantification Figure S6 Rubber stem density in biodiversity and yield datasets. Figure S7 Comparison of a) agrodiversity, b) fruit tree stem density and c) timber tree stem density of AF plots between yield and biodiversity datasets. Figure S8 Variation in species richness among districts, analysed to decide whether to include district as a random effects in models of species richness response. Figure S9 Influence of rainfall on butterfly species richness, analysed to decide whether to include rainfall as a random effects in models of species richness response. Figure S10 Influence of sampling trap-days on butterfly species richness, analysed to decide whether to include trap-days as a random effects in models of species richness response. Figure S11 Comparison of rubber yields in AF and MO plots within soil types Figure S12 Habitat structure measures of rubber agroforests (AF) and monocultures (MO) in biodiversity dataset plots. -

Theorems in Quran About the Creation of Insects and Its Diversity in Undaan Park Surabaya

JOURNAL INTELLECTUAL SUFISM RESEARCH (JISR) e-ISSN : 2622-2175 p-ISSN : 2621-0592 JISR 1(2), Mei 2019, 5-10 Email : [email protected] Theorems in Quran about the Creation of Insects and Its Diversity in Undaan Park Surabaya N „Aini1, I A Wira2, V Y Pratami3 1Islamic Building School of Jagad Alimussirry Surabaya, Indonesia 2Biology Postgraduate Program, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia 3Biology Postgraduate Program, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract. In the Al-quran there are many verses that explain the animals that exist in this universe, one of which is about Insect. The research on Insect diversity around the Surabaya Undaan Park aims to describe the diversity of Insects and compare the number of members of each order in the Insect class around the Surabaya Undaan Park and look for their relevance to the Qur'anic proposition about the creation of Insects. The method used in this research assignment was observation, which was to go directly to the field to catch Insects in 5 plots in the vicinity of Surabaya Undakan Park with 4 repetitions in each plot, then collect data to be identified. Based on the results of observations, collection and identification, it can be found that there are various Insects in the area. This was evidenced by the discovery of various orders from Insectas, among others: Order Lepidoptera, Order Odonata, Order Hymenoptera, Order Diptera, and Order Orthoptera. Comparison of the number of species from each order is different. The most dominant number of species is in the order of Lepidoptera which was then followed by the order Hymenoptera. -

Development of Encyclopedia Boyong Sleman Insekta River As Alternative Learning Resources

PROC. INTERNAT. CONF. SCI. ENGIN. ISSN 2597-5250 Volume 3, April 2020 | Pages: 629-634 E-ISSN 2598-232X Development of Encyclopedia Boyong Sleman Insekta River as Alternative Learning Resources Rini Dita Fitriani*, Sulistiyawati Biological Education Faculty of Science and Technology, UIN Sunan Kalijaga Jl. Marsda Adisucipto Yogyakarta, Indonesia Email*: [email protected] Abstract. This study aims to determine the types of insects Coleoptera, Hemiptera, Odonata, Orthoptera and Lepidoptera in the Boyong River, Sleman Regency, Yogyakarta, to develop the Encyclopedia of the Boyong River Insect and to determine the quality of the encyclopedia developed. The method used in the research inventory of the types of insects Coleoptera, Hemiptera, Odonata, Orthoptera and Lepidoptera insects in the Boyong River survey method with the results of the study found 46 species of insects consisting of 2 Coleoptera Orders, 2 Hemiptera Orders, 18 orders of Lepidoptera in Boyong River survey method with the results of the research found 46 species of insects consisting of 2 Coleoptera Orders, 2 Hemiptera Orders, 18 orders of Lepidoptera in Boyong River survey method. odonata, 4 Orthopterous Orders and 20 Lepidopterous Orders from 15 families. The encyclopedia that was developed was created using the Adobe Indesig application which was developed in printed form. Testing the quality of the encyclopedia uses a checklist questionnaire and the results of the percentage of ideals from material experts are 91.1% with very good categories, 91.7% of media experts with very good categories, peer reviewers 92.27% with very good categories, biology teachers 88, 53% with a very good category and students 89.8% with a very good category. -

Biji, Perkecambahan, Dan Potensinya 147‐153 RONY IRAWANTO, DEWI AYU LESTARI, R

Seminar Nasional& International Conference Pros Sem Nas Masy Biodiv Indon vol. 3 | no. 1 | pp. 1‐167 | Februari 2017 ISSN: 2407‐8050 Tahir Awaluddin foto: , Timur Kalimantan Derawan, di Penyelenggara & Pendukung tenggelam Matahari | vol. 3 | no. 1 | pp. 1-167 | Februari 2017 | ISSN: 2407-8050 | DEWAN PENYUNTING: Ketua, Ahmad Dwi Setyawan, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta Anggota, Sugiyarto, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta Anggota, Ari Pitoyo, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta Anggota, Sutomo, UPT Balai Konservasi Tumbuhan Kebun Raya “Eka Karya”, LIPI, Tabanan, Bali Anggota, A. Widiastuti, Balai Besar Pengembangan Pengujian Mutu Benih Tanaman Pangan dan Hortikultura, Depok Anggota, Gut Windarsih, Pusat Penelitian Biologi, LIPI, Cibinong, Bogor Anggota, Supatmi, Pusat Penelitian Bioteknologi, LIPI, Cibinong, Bogor PENYUNTING TAMU (PENASEHAT): Artini Pangastuti, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta Heru Kuswantoro, Balai Penelitian Tanaman Aneka Kacang dan Umbi, Malang Nurhasanah, Universitas Mulawarman, Samarinda Solichatun, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta Yosep Seran Mau, Universitas Nusa Cendana, Kupang PENERBIT: Masyarakat Biodiversitas Indonesia PENERBIT PENDAMPING: Program Biosains, Program Pascasarjana, Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta Jurusan Biologi, FMIPA, Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta PUBLIKASI PERDANA: 2015 ALAMAT: Kantor Jurnal Biodiversitas, Jurusan Biologi, Gd. A, Lt. 1, FMIPA, Universitas Sebelas Maret Jl. Ir. Sutami 36A Surakarta 57126. Tel. & Fax.: +62-271-663375, Email: [email protected] -

Environmental Impact Assessment

Environmental Impact Assessment December 2013 IND: SASEC Road Connectivity Investment Program (formerly SASEC Road Connectivity Sector Project) Asian Highway 2 (India /Nepal Border to India/Bangladesh Border) Asian Highway 48 (India/Bhutan Border to India/Bangladesh Border) Prepared by Ministry of Roads Transport and Highways, Government of India and Public Works Department, Government of West Bengal for the Asian Development Bank. This is a revised version of the draft originally posted in July 2013 available on http://www.adb.org/projects/47341- 001/documents/. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 30 April 2013) Currency unit – Indian rupee (INR) INR1.00 = $ 0.01818 $1.00 = INR 55.00 ABBREVIATION AADT Annual Average Daily Traffic AAQ Ambient air quality AAQM Ambient air quality monitoring ADB Asian Development Bank AH Asian Highway ASI Archaeological Survey of India BDL Below detectable limit BGL Below ground level BOD Biochemical oxygen demand BOQ Bill of quantity CCE Chief Controller of Explosives CGWA Central Ground Water Authority CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species CO Carbon monoxide COD Chemical oxygen demand CPCB Central Pollution Control Board CSC Construction Supervision Consultant DFO Divisional Forest Officer DG Diesel generating set DO Dissolved oxygen DPR Detailed project report E&S Environment and social EA Executing agency EAC Expert Appraisal Committee EFP Environmental Focal Person EHS Environment Health and Safety EIA Environmental impact assessment EMOP Environmental monitoring plan EMP Environmental -

Catalogue of the Type Specimens of Lepidoptera Rhopalocera in the Hill Museum

Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries CATALOGUE OF THE Type Specimens of Lepidoptera Rhopalocera IN THE HILL MUSEUM BY A. G. GABRIEL, F.E.S. Issued June, 1932 LONDON JOHN BALE, SONS & DANIELSSON, LTD. 83-91, GBEAT TITCHFIELD STEEET, OXEOED STEEET, W. 1 1932 Price 20/- Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Unfortunately Mr. Joicey did not live to see the publication of this Catalogue. It will however remain, together with the four completed volumes of the " Bulletin of the Hill Museum," as a lasting memorial to to the magnificent collection of Lepidoptera amassed by Mr. Joicey, and to the work carried out at the Hill Museum under his auspices. G. Talbot. Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries CATALOGUE OF THE TYPE SPECIMENS OF LEPIDOPTERA RHOPALOCERA IN THE HILL MUSEUM. By A. G. GABRIEL, F.E.S. INTRODUCTION BY G. TALBOT. It is important to know exactly where type specimens are to be found. The British Museum set an example by publishing catalogues of some of their Rhopalocera types, and we hope this will be continued. Mr. Gabriel, who was responsible for that work, has been asked by Mr. Joicey to prepare a catalogue for the Hill Museum. The original description of almost every name in this catalogue has been examined for the correct reference, and where the sex or habitat was wrongly quoted, the necessary correction has been made. -

Diversity Pattern of Butterfly Communities (Lepidoptera

International Scholarly Research Network ISRN Zoology Volume 2011, Article ID 818545, 8 pages doi:10.5402/2011/818545 Research Article DiversityPatternofButterflyCommunities (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidae) in Different Habitat Types in a Tropical Rain Forest of Southern Vietnam Lien Van Vu1 and Con Quang Vu2 1 Department of Biology, Vietnam National Museum of Nature, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Nghia Do, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Vietnam 2 Department of Insect Ecology, Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Nghia Do, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Vietnam Correspondence should be addressed to Lien Van Vu, [email protected] Received 26 January 2011; Accepted 1 March 2011 Academic Editors: M. Griggio and V. Tilgar Copyright © 2011 L. V. Vu and C. Quang Vu. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Diversity of butterfly communities of a tropical rain forest of Bu Gia Map National Park in South Vietnam was studied in four different habitat types (the natural forest, the disturbed forest, the bamboo forest, and the stream sides in the forest) in December 2008 and April 2009. A total of 112 species with 1703 individuals of Papilionoidae (except Lycaenidae) were recorded. The proportion of rare species tends to decrease from the natural forest to the stream sides, while the proportion of common species tends to increase from the natural forest to the stream sides. The stream sides have the greatest individual number, while the disturbed forest contains the greatest species number. The bamboo forest has the least species and individual numbers.