Non-Frontal Pressure Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Weather the Weather

The weather Área Lectura y Escritura Resultados de aprendizaje Conocer vocabulario relacionado al clima. Utilizar vocabulario relacionado al clima en contextos de escritura formal. Contenidos 1. General vocabulary words Debo saber - Simple present - Present continuous - Simple past - Past continuous The Weather Cold weather In Scandinavia, the chilly (1) days of autumn soon change to the cold days of winter. The first frosts (2) arrive and the roads become icy. Rain becomes sleet (3) and then snow, at first turning to slush (4) in the streets, but soon settling (5), with severe blizzards (6) and snowdrifts (7) in the far north. Freezing weather often continues in the far north until May or even June, when the ground starts to thaw (8) and the ice melts (9) again. - (1) cold, but not very - (2) thin white coat of ice on everything - (3) rain and snow mixed - (4) dirty, brownish, half- snow, half – water - (5) staying as a white covering - (6) snow blown by high winds - (7) Deep banks of snow against walls, etc. - (8) change from hard, frozen state to normal - (9) change from solid to liquid under heat Servicios Académicos para el Acompañamiento y la Permanencia - PAIEP Primera Edición - 2016 En caso de encontrar algún error, contáctate con PAIEP-USACH al correo: [email protected] 1 Warm / hot weather - Close: warm and uncomfortable. - Stifling: hot, uncomfortable, you can hardly breathe. - Humid: hot and damp, makes you sweat a lot. - Scorching: very hot, often used in positive contexts. - Boling: very hot, often used in negative contexts - Mild: warm at a time when it is normally cold - Heat wave last month: very hot, dry period Wet weather This wet weather scale gets stronger from left to right. -

WMO Solid Precipitation Measurement Intercomparison--Final Report

W O R L D M E T E O R O L O G I C A L O R G A N I Z A T I O N INSTRUMENTS AND OBSERVING METHODS R E P O R T No. 67 WMO SOLID PRECIPITATION MEASUREMENT INTERCOMPARISON FINAL REPORT by B.E. Goodison and P.Y.T. Louie (both Canada) and D. Yang (China) WMO/TD - No. 872 1998 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This report has been produced without editorial revision by the WMO Secretariat. It is not an official WMO publication and its distribution in this form does not imply endorsement by the Organization of the ideas expressed. FOREWORD The WMO Solid Precipitation Measurement Intercomparison was started in the northern hemisphere winter of 1986/87. The field work was carried out in 13 Member countries for seven years. The Intercomparison was the result of Recommendation 17 of the ninth session of the Commission for Instruments and Methods of Observation (CIMO-IX). As in previous WMO intercomparisons of rain gauges, the main objective of this test was to assess national methods of measuring solid precipitation against methods whose accuracy and reliability were known. It included past and current procedures, automated systems and new methods of observation. The experiment was designed to determine especially wind related errors, and wetting and evaporative losses in national methods of measuring solid precipitation. -

Student Name: ______Date: ______

Water Cycle Vocabulary Worksheet Student Name: _______________________ Date: _________ Teacher Name: LaTrecia Abero Score: _________ Define these terms: Atmosphere The different layers of gases that extend from the surface of the Earth into space. Boiling This is the change from a liquid to a gas. Boiling Point This is a temperature where the vapor pressure of a liquid equals the atmospheric pressure. Cloud The result of evaporation, this is a visible body of fine water droplets or ice particles suspended in Earth's atmosphere. Condensation This is the process of matter changing from a gaseous state to a liquid state. Dew This is when water vapor in the air condenses directly onto a surface, usually seen in the morning. Earth The third planet from the sun. Evaporation This is another term for vaporization, the part of the water cycle in which water changes from a liquid to a gas. Water moves from bodies of water on Earth to water vapor in the atmosphere. Fog This is a low-lying cloud. This is a collection of liquid water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air at or near the Earth's surface. Freezing This is the process of matter changing from the liquid to the solid state. Groundwater This is water stored in the spaces between rocks inside Earth that is found within a few miles of the Earth's surface. Hail This is pellets of frozen rain that fall in showers from cumulonimbus clouds. Heat The transfer of thermal energy between two bodies which are at different temperatures. The SI unit for this is the Joule. -

Print Key. (Pdf)

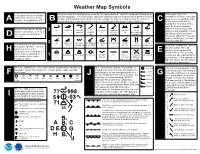

Weather Map Symbols Along the center, the cloud types are indicated. The top symbol is the high-level cloud type followed by the At the upper right is the In the upper left, the temperature mid-level cloud type. The lowest symbol represents low-level cloud over a number which tells the height of atmospheric pressure reduced to is plotted in Fahrenheit. In this the base of that cloud (in hundreds of feet) In this example, the high level cloud is Cirrus, the mid-level mean sea level in millibars (mb) A example, the temperature is 77°F. B C C to the nearest tenth with the cloud is Altocumulus and the low-level clouds is a cumulonimbus with a base height of 2000 feet. leading 9 or 10 omitted. In this case the pressure would be 999.8 mb. If the pressure was On the second row, the far-left Ci Dense Ci Ci 3 Dense Ci Cs below Cs above Overcast Cs not Cc plotted as 024 it would be 1002.4 number is the visibility in miles. In from Cb invading 45° 45°; not Cs ovcercast; not this example, the visibility is sky overcast increasing mb. When trying to determine D whether to add a 9 or 10 use the five miles. number that will give you a value closest to 1000 mb. 2 As Dense As Ac; semi- Ac Standing Ac invading Ac from Cu Ac with Ac Ac of The number at the lower left is the a/o Ns transparent Lenticularis sky As / Ns congestus chaotic sky Next to the visibility is the present dew point temperature. -

Wayand Washington 0250E 15

Observation, Simulation, and Evaluation of Snow Dynamics in the Transitional Snow Zone Nicholas E. Wayand A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Jessica D. Lundquist (Chair) Bart Nijssen Martyn P. Clark Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering i ©Copyright 2016 Nicholas E. Wayand ii University of Washington Abstract Observation, Simulation, and Evaluation of Snow Dynamics in the Transitional Snow Zone Nicholas E. Wayand Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Jessica D. Lundquist Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering The frequent mid-winter accumulation and ablation cycles of snowpack within the rain-snow transitional zone play an important role for the maritime basins along the western U.S. mountain ranges. Representation of transitional snowpack within hydrological models has remained a challenge, largely because surface and meteorological conditions frequently remain near the freezing point, which allows large errors in modeled accumulation or ablation to result from small forcing or structural errors. This research aims to improve model representation of accumulation and ablation processes by utilizing new observations within the transitional snow zone combined with novel methods of model evaluation. The importance of mid-winter snowmelt during historical flooding events was assessed over three maritime basins in the western US. A physically-based snow model was coupled with an idealized basin representation to quantity how the characteristics of each basin combined with storm strength to control the distribution of snowmelt over a basin. Snowmelt contributions to total basin runoff ranged from 7-29% during historic flooding events between 1980 and 2008. -

Documentation for Selected Reference Tables in the Archive Database Version 1.0 October 9, 2002

Documentation for Selected Reference Tables in the Archive Database Version 1.0 October 9, 2002 1.0 General Information Several tables in the archive database have already been populated for the River Forecast Center (RFC). These tables are: huc2, huc4, huc6, huc8, country, state, counties, rfc, wfo_hsa, shefdur, shefpe, shefpe1, shefpetrans, shefprob, shefqc, shefts and datalimits. The contents of these tables are discussed in the following sections. The RFC Archive Team is aware of efforts led by a Central Region (CR) team to standardize selected reference tables in the IHFS database. Whenever possible an effort has been made to be consistent with the guidelines being developed by the CR team but there may be some differences. The archive database is delivered with these tables already defined. The load files and run_load-xref script can be found in /arc/xref-data directory. 2.0 Hydrologic Unit Code Tables Source of the data for these four tables was obtained from USGS website. Detailed information about the hydrologic unit codes (huc) can be found at the following site: http://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/sparrow/wrr97/geograp/geograp.html . A brief explanation of the HUC obtained from this site is as follows: “An eight-digit code uniquely identifies each of the four levels of classification within four two-digit fields. The first two digits identify the water-resources region; the first four digits identify the sub-region; the first six digits identify the accounting unit, and the addition of two more digits for the cataloging unit completes the eight-digit code. An example is given here using hydrologic unit code (HUC) 01080204: 01 - the region 0108 - the sub-region 010802 - the accounting unit 01080204 - the cataloging unit 1 An 00 in the two-digit accounting unit field indicates that the accounting unit and the sub-region are the same. -

Whitefield Votes Yes for New Municipal Building

www.newhampshirelakesandmountains.com Publishing news & views of Lancaster, Groveton, Whitefield, Lunenburg & other towns of the upper Connecticut River valley of New Hampshire & Vermont [email protected] VOL. CXLVII, NO. 12 WEDNESDAY, MARCH 19, 2014 LANCASTER, NEW HAMPSHIRE TELEPHONE: 603-788-4939 TWENTY-FOUR PAGES 75¢ Despite 75% state aid, WMRSD voters nix $18 million CTE project BY EDITH TUCKER 141; and Dalton, 113 to 136. [email protected] Only 47.19 percent of the WHITEFIELD — The 2,017 voters said “yes” at White Mountains Region- the polls this year. al School District school On March 11, 925 vot- board didn’t close the sale. ers cast “yes” votes, and Almost the same num- 1,035, “no,” plus 57 blanks, ber of voters said “yes” to making a total of 2,017 bal- the proposed $18 million lots. Under SB2, passage Career and Technical Ed- of a bond issue requires a ucation (CTE) project on 3/5ths super-majority of 60 March 11 as in last year’s percent. effort, but the number of This year’s count fell “no” votes swelled by 267 short by nearly 13 percent; over a similar effort on blanks do not count when March 12, 2013. percentages are computed. Despite a guarantee of Last year a warrant arti- a whopping 75 percent in cle for the same purpose re- state aid that would have ceived 54.76 percent of the reduced the District’s di- “yes” votes after the March rect cost to some $4.5 mil- 19 recount, only slightly lion, a majority of voters in more than five percent DARIN WIPPERMAN/LITTLETON COURIER all five SAU 36 towns voted short of passage. -

Improving Predictions of Precipitation Type at the Surface: Description and Verification of Two New Products from the ECMWF Ensemble

FEBRUARY 2018 G A S C Ó NETAL. 89 Improving Predictions of Precipitation Type at the Surface: Description and Verification of Two New Products from the ECMWF Ensemble ESTÍBALIZ GASCÓN,TIM HEWSON, AND THOMAS HAIDEN European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, Reading, United Kingdom (Manuscript received 9 August 2017, in final form 7 November 2017) ABSTRACT The medium-range ensemble (ENS) from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Integrated Forecasting System (IFS) is used to create two new products intended to face the challenges of winter precipitation-type forecasting. The products themselves are a map product that repre- sents which precipitation type is most likely whenever the probability of precipitation is .50% (also including information on lower probability outcomes) and a meteogram product, showing the temporal evolution of the instantaneous precipitation-type probabilities for a specific location, classified into three categories of pre- cipitation rate. A minimum precipitation rate is also used to distinguish dry from precipitating conditions, setting this value according to type, in order to try to enforce a zero frequency bias for all precipitation types. The new products differ from other ECMWF products in three important respects: first, the input variable is discretized, rather than continuous; second, the postprocessing increases the output information content; and, third, the map-based product condenses information into a more accessible format. The verification of both products was developed using four months’ worth of 3-hourly observations of present weather from manual surface synoptic observation (SYNOPs) in Europe during the 2016/17 winter period. This verification shows that the IFS is highly skillful when forecasting rain and snow, but only moderately skillful for freezing rain and rain and snow mixed, while the ability to predict the occurrence of ice pellets is negligible. -

Frequencies and Characteristics of Global Oceanic Precipitation

[Reprinted from BUl.l EtlN ()F I ItE AMI RI( .\N MI II ()ROI.O(iI( _,1 SO( II l,,. \"¢_1. 76, No. 0. ,'<,cptcnd_er 1005] Printed in U. S. A. Grant W. Petty Frequencies and Characteristics Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, of Global Oceanic Purdue University, Precipitation from Shipboard West Lafayette, Indiana Present-Weather Reports NASA-CR-204894 Abstract 1. Introduction Ship reports of present weather obtained from the Comprehen- The need for an accurate global precipitation clima- sive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set are analyzed for the period tology over the ocean has been recognized for many 1958-91 in order to elucidate regional and seasonal variations in the decades, owing to the key role played by oceanic climatological frequency, phase, intensity, and character of oceanic precipitation. Specific findings of note include the following: precipitation in the general circulation of the atmo- sphere and in the global hydrological and geochemi- 1) The frequency of thunderstorm reports, relative to all precipita- cal cycles. Because it is the average precipitation rate tion reports, is a strong function of location, with thunderstorm (or average monthly precipitation accumulation) that activity being favored within 1000-3000 km of major tropical and is of greatest direct importance for studies of atmo- subtropical landmasses, while being quite rare at other locations, even within the intertropical convergence zone. spheric energetics and moisture budgets, most re- 2) The latitudinal frequency of precipitation over the southern search to date has focused on the estimation of this oceans increases steadily toward the Antarctic continent and variable by various means. -

Crowdsourcing of Weather Data on Mobile App and Deep Learning

Crowdsourcing of Weather Data on Mobile App and Deep Learning Lior Perez 99th AMS annual meeting Crowdsourcing on Meteo-France mobile app ■ Context: ― fewer resources devoted to human observation ■ Crowdsourcing can help: ― To get a high density of human observations ― To get information on impacts of weather events ■ Dedicated observation app: NO ― Too difficult to get a large audience ■ Add a crowdsourcing module in our general public app ― Benefit from a 1M visitors per day audience Keep it simple ■ We wanted maximum participation rate Keep it simple! A challenge for our culture of weather experts... In first version: ■ Only immediate observation ■ Only for geolocalized users ■ No quantitative observation ■ Very few details in each observation Feedback and gamification to increase user engagement Success in quantity and quality ■ 10k to 40k observations every day ■ Approx 1000 obs / h disseminated on all the French territory ■ Good quality, very few outliers ■ Large increase of observations rate in severe weather (13 observations of a tornado at 1am) Outliers filtering ■ Methods investigated: ― Obvious outliers removal ► For instance: Hail + Fog + Sun + Strong wind ― Anomaly detection using the multivariate gaussian distribution, to detect unreliable users ■ Conclusions: ― Most unreliable users don’t come back ― Returning users are generally reliable ― Fake observations < 1% What are we doing with the data? Internal visualization interface for forecasters Subjective product validation ■ Product : distinction of hydrometeors No precipitation -

THE CASE for ONSPOT a Fleet Manager’S Guide to Safety and Traction Control the CASE for ONSPOT

THE CASE FOR ONSPOT A fleet manager’s guide to safety and traction control THE CASE FOR ONSPOT Icy road basics for safe driving To many, the white winter landscape is the definition of icy roads. There are different reasons why roads become icy based on weather conditions and meteorology. For safe driving, it’s a good idea to know some theory behind icy roads. So, let’s have a closer look at some common causes for roads to become icy. With proper knowledge and awareness, the driver can reduce the risk of accidents or delays due to slippery road conditions. What makes winter roads icy? Snow turns into ice Freezing rain and drizzle Deep snow on the road could be an obstacle that While rainwater can make roads slippery, rain- needs to be plowed. But, even if many of us have covered roads are far from being as slippery as experienced spinning wheels in deep snow, most ice-covered roads. Normally, when temperature is accidents occur in light snowfalls. This is probably above freezing, it doesn’t snow – it rains. So, how because we’re more prepared and cautious in could there be ice when it rains? Meteorology, the heavy snow. But, in temperatures below freezing, science of weather, can explain this phenomena. how can roads with dry snow become icy roads? It’s Precipitation may pass several layers of air, and a combination of two things: First, the weight of the these air layers can have different temperatures. If vehicle compresses the fluffy snow into a compact temperature in the clouds are well above freezing, layer of snow. -

February 2016 Storm Data Publication

FEBRUARY 2016 VOLUME 58 NUMBER 2 STORM DATA AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION NCEI NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE NATIONAL CENTERS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION Cover: This cover represents a few weather conditions such as snow, hurricanes, tornadoes, heavy rain and flooding that may occur in any given location any month of the year. (Photos courtesy of NCEI) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Storm Data and Unusual Weather……………………………………………………………………..3 Additions....................………………………………...…………………………………………….259 Corrections........…………………………………….……………………………………………....268 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Centers For Environmental Information Editor: Sherri Nave STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Centers For Environmental Information (NCEI), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events resulting in deaths, injuries, and damage are compiled by the National Centers For Environmental Information (NCEI) and the National Weather Service’s (NWS) Storm Prediction Center. STORM DATA contains all confirmed information on storms available to our staff at the time of publication. Late reports and corrections will be printed in each