Presenting an Innocent Nation- Critique of Gojira.Pdf (504Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bamcinématek Presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 Tales of Rampaging Beasts and Supernatural Terror

BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 tales of rampaging beasts and supernatural terror September 21, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, October 26 through Thursday, November 1 BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, a series of 10 films showcasing two strands of Japanese horror films that developed after World War II: kaiju monster movies and beautifully stylized ghost stories from Japanese folklore. The series includes three classic kaiju films by director Ishirô Honda, beginning with the granddaddy of all nuclear warfare anxiety films, the original Godzilla (1954—Oct 26). The kaiju creature features continue with Mothra (1961—Oct 27), a psychedelic tale of a gigantic prehistoric and long dormant moth larvae that is inadvertently awakened by island explorers seeking to exploit the irradiated island’s resources and native population. Destroy All Monsters (1968—Nov 1) is the all-star edition of kaiju films, bringing together Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra, and King Ghidorah, as the giants stomp across the globe ending with an epic battle at Mt. Fuji. Also featured in Ghosts and Monsters is Hajime Satô’s Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell (1968—Oct 27), an apocalyptic blend of sci-fi grotesquerie and Vietnam-era social commentary in which one disaster after another befalls the film’s characters. First, they survive a plane crash only to then be attacked by blob-like alien creatures that leave the survivors thirsty for blood. In Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku (1960—Oct 28) a man is sent to the bowels of hell after fleeing the scene of a hit-and-run that kills a yakuza. -

KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin with Leah Wilson

Other Titles in the Smart Pop Series Taking the Red Pill Science, Philosophy and Religion in The Matrix Seven Seasons of Buffy Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Television Show Five Seasons of Angel Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Vampire What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue Stepping through the Stargate Science, Archaeology and the Military in Stargate SG-1 The Anthology at the End of the Universe Leading Science Fiction Authors on Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Finding Serenity Anti-heroes, Lost Shepherds and Space Hookers in Joss Whedon’s Firefly The War of the Worlds Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic Alias Assumed Sex, Lies and SD-6 Navigating the Golden Compass Religion, Science and Dæmonology in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials Farscape Forever! Sex, Drugs and Killer Muppets Flirting with Pride and Prejudice Fresh Perspectives on the Original Chick-Lit Masterpiece Revisiting Narnia Fantasy, Myth and Religion in C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles Totally Charmed Demons, Whitelighters and the Power of Three An Unauthorized Look at One Humongous Ape KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin WITH Leah Wilson BENBELLA BOOKS • Dallas, Texas This publication has not been prepared, approved or licensed by any entity that created or produced the well-known movie King Kong. “Over the River and a World Away” © 2005 “King Kong Behind the Scenes” © 2005 by Nick Mamatas by David Gerrold “The Big Ape on the Small Screen” © 2005 “Of Gorillas and Gods” © 2005 by Paul Levinson by Charlie W. -

Creature Double Feature: America’S Encounter with Godzilla, the King of Monsters

Creature Double Feature: America’s Encounter with Godzilla, the King of Monsters Gus Huiskamp Senior Division Historical Paper Paper Length: 2,020 Words The Godzilla film franchise has long been cherished as a comically odd if not ludicrous cultural icon in the realm of science fiction; however, this representation misses the deep-rooted significance of the original film and reduces the series from high grade, culturally aware cinema to trivial “monster movies.” In the words of William Tsutsui, both an Ivy League scholar and a lifelong Godzilla fan, the original and powerfully meaningful Gojira film1 watched as many of its successors “degenerated into big-time wrestling in seedy latex suits.”2 In spite of its legacy’s deterioration, however, the initial film retains its integrity and significance. Although the altered version of the film had significant financial success in the United States, Toho Company’s Gojira is not widely recognized for its philosophical and cultural significance in this foreign sphere. To a considerable extent, the American encounter with the film has failed due to nativism and prejudice, and in the intercultural exchange the film has lost some of its literary depth, as well as the poignancy in its protest against nuclear proliferation and destructive science in general. When Gojira was released in 1954, the Japanese audience whom it met was still traumatized by the brutal incendiary and atomic attacks of World War II, post-war economic distress, and continuing off-shore nuclear experimentation by the United States. All of these factors contributed to a national “victim” identity as well as a general sense of crisis among the struggling citizens.3 What is also significant of these cultural surroundings is that they were largely caused by an American hand, either directly or indirectly. -

Highlights of Film-Related Events Marking Anniversary Year at Fall's

PRESS RELEASE July 31, 2017 Highlights of Film-Related Events Marking Anniversary Year at Fall’s Biggest Film Festival The Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF) will host an exciting lineup of special events to celebrate its 30th anniversary edition, including Godzilla Cinema Concerts with a live symphony orchestra, festive all-night events, free open-air screenings, and classic film screenings. The 30th TIFF will take place October 25 – November 3, 2017 at Roppongi Hills, EX Theater Roppongi and other venues in Tokyo. 30th Tokyo International Film Festival Special Program: Godzilla Cinema Concert Godzilla has made the highest number of appearances at the festival - and this year, will appear again at TIFF’s first cinema concert, with special guests and a screening with live orchestra. We will screen the original Godzilla film (1954), directed by Ishirō Honda, accompanied by the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, performing the iconic soundtrack written by Akira Ifukube. Conductor Kaoru Wada, a pupil of Ifukube’s, will direct, with the choir group Chor June. Prior to the screening and live performance, there will be a talk show Godzilla: Present, Past, Future, bringing together for the first time three generations of Godzilla series creators, namely Haruo Nakajima (Godzilla suit actor), Shogo Tomiyama (Heisei TM&©TOHO CO.,LTD. series producer), and Shinji Higuchi (Shin Godzilla director) to talk about what attracts new generations of fans to Godzilla. Date and times: October 31, 2017 (Tue) (1st screening) Doors open 14:15 / Starts 15:00 -

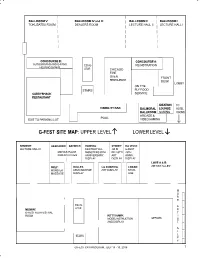

G-Fest Site Map: Upper Level Lower Level

BALLROOM V: BALLROOM IV and III: BALLROOM II: BALLROOM I: TOKUSATSU ROOM DEALERS ROOM LECTURE HALL II LECTURE HALL I CONCOURSE B: CONCOURSE A: AUTOGRAPHS AND G-FANS ESCAL- REGISTRATION HELPING G-FANS ATOR CHICAGO FIRE OVEN FRONT RESTAURANT DESK LOBBY ON THE STAIRS FLY FOOD CADDYSHACK SERVICE RESTAURANT IDEATION TO VISIBILITY BAR BALMORAL LOUNGE: HOTEL BALLROOM: GAMING ROOMS ARCADE & POOL EXIT TO PARKING LOT VIDEOGAMING G-FEST SITE MAP: UPPER LEVEL LOWER LEVEL KENNEDY: HEATHROW GATWICK HANEDA: SYDNEY DA VINCI: LECTURE HALL III DESTROY ALL JOHN G-FEST MINYA’S PLACE MONSTERS 50TH BELLOTTI 25TH KIDS ACTIVITIES ANNIVERSARY ART ANNIV. DISPLAY DISPLAY DISPLAY LOVE A & B: ORLY: DULLES: LA GUARDIA: LOGAN: ARTIST ALLEY MONSTER KEIZO MURASE ART DISPLAY STOR- MASSAGE DISPLAY AGE M O R E ESCAL- A ATOR MIDWAY: R G-FEST FILM FESTIVAL T ROOM KITTY HAWK: I MODEL INSTRUCTION OFFICES S AND DISPLAY T A L L STAIRS E Y G-FEST XXV PROGRAM, JULY 13 - 15, 2018 7 FRIDAY, JULY 13, 2018 SESSIONS SESSIONS SESSIONS GAMING FILM MODEL ARTISTS MECHA-G TOKUSATSU DEALERS OTHER FESTIVAL THREAD ALLEY ARCADE SESSIONS ROOM BALLROOM 1 BALLROOM 2 KENNEDY IDEATION MIDWAY KITTY HAWK LOVE A&B BALMORAL BALLROOM 5 BLRM 3 & 4 9:00 AFTER THE BOOM 50th REGISTRA- Anniversary TION (all day) OPENS 10:00 GENERAL MINYA’S Display KAIJU FILMS, GAMING PLACE Room open DOJO STYLE OPENS AT for drop-off, Alaena Gavins then viewing 10:00 AM in 11:00 HEATHROW & G-FEST KAIJU DESTROY COSTUMING GATWICK. ORIENTATION ASSAULT ALL PANEL Coloring and SESSION: TOURNEY DRAGONS Sean crafts for young J.D. -

In This Issue

In This Issue: Fairyland’s new Album Warp 11 Shadowless Sword Kwaidan Vampire Gigolo Basilisk Anime and... Contents: ∏Godzilla: Final Wars Page 3 ≥Fairyland Page 17 æBasilisk Anime Page 13 ∑ Shadowless Sword ∏Kawaidan Page 8 Page 21 ØWarp 11 Vampire Host Page 24 æ Page 27 Godzilla: Final Wars that the Japanese suitmation is better, the real Godzilla was performed (Gojira: Fainaru Uozu) by an actor in costume. Japan 2004 When the two finally battle it out, ‘Zilla is quickly dispatched, Directed by Ryuhei Kitamura almost as an afterthought. The evil alien overlord who is controlling all the monsters on Earth, except for Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Godzilla of course, remarks that he never should premier kaiju franchise, Godzilla: Final Wars is have put his faith in that “tuna-eating” both a tribute to the history of the series and disappointment. an answer to the horrible American movie There’s also a lame scene set in New York carrying the Godzilla name. City just before Rodan destroys it that plays Toho Studios was not pleased with on Japanese stereotypes of Americans. the U.S. version of Godzilla, nor were None of the other international cities most Godzilla fans, and Final Wars is that are wasted during the film, such clearly an attempt to bring the big guy as Paris and Shanghai, receive this home, even more so than Godzilla 2000 and treatment. the other post-U.S. Godzilla movies. There are In addition to taking shots at the U.S. a number of pot shots at the U.S. -

From Screen to Page: Japanese Film As a Historical Document, 1931-1959

FROM SCREEN TO PAGE: JAPANESE FILM AS A HISTORICAL DOCUMENT, 1931-1959 by Olivia Umphrey A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University May 2009 © 2009 Olivia Umphrey ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Olivia Anne Umphrey Thesis Title: From Screen to Page: Japanese Film as a Historical Document, 1931- 1959 Date of Final Oral Examination: 03 April 2009 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Stephanie Stacey Starr, and they also evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination, and that the thesis was satisfactory for a master’s degree and ready for any final modifications that they explicitly required. L. Shelton Woods, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Lisa M. Brady, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Nicanor Dominguez, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by L. Shelton Woods, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by John R. Pelton, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank her advisor, Dr. Shelton Woods, for his guidance and patience, as well as her committee members, Dr. Lisa Brady and Dr. Nicanor Dominguez, for their insights and assistance. iv ABSTRACT This thesis explores to what degree Japanese film accurately reflects the scholarly accounts of Japanese culture and history. -

Elements, the Undergraduate Research Journal of Boston College, Showcases the Varied Research Endeavors of Fellow Undergraduates to the Greater Academic Community

E Mission stateMent Elements, the undergraduate research journal of Boston College, showcases the varied research endeavors of fellow undergraduates to the greater academic community. By fostering intellectual curiosity and discussion, the journal strengthens and affirms the community of undergraduate students at Boston College. Elements Spring 2016 Thanks ElEmEnts staff We would like to thank Boston College, the Institute for the Liberal Editors-in-chiEf social sciEncEs Arts, and the Office of the Dean for the Morrissey College of Arts and Marissa Marandola sydnEy applE, Senior Editor Sciences for the financial support that makes this issue possible. BEtty (yunqing) Wang MichEllE Kang, Senior Editor Erica oh, Editor QuEsTions & ConTribuTions Managing Editor reed piErcEy, Editor anniE KiM If you have any questions, please contact the journal at natural sciEncEs [email protected]. All submissions can be sent to elements. Deputy Editor david fu, Senior Editor [email protected]. Visit our website at www.bc.edu/elements alEssandra luEdeking dErek Xu, Editor for updates and further information. trEasurEr MEdia & puBlicity CovEr ashEr (sEungWan) Kang annE donnElly, Senior Editor © Bénigne Gagneraux / Wikimedia Commons MadElinE gEorgE, Assistant Editor layout PEriodiCiTy Xizi (kelsEy) zhang, Senior Editor web Editor Elements is published twice an academic year in the fall and spring ElisE hon, Assistant Editor MinKi hong, Senior Editor semesters. shuang li, Editor thao vu, Editor officE ManagEr ElECTroniC Journal Billy huBschMan Elements is also published as an open access electronic journal. huManitiEs It is available at http://ejournals.bc.edu/ojs/index.php/elements. JacoB ciafonE, Senior Editor faculty advisors ISSN 2380-6087 isabella doW, Senior Editor Jason cavallari siErra DennEhy, Editor ElizaBEth chadWicK ciaran dillon-davidson, Editor The information provided by our contributors is not independently verified byElements. -

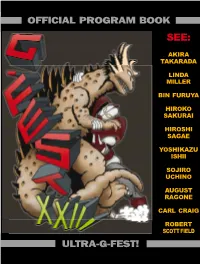

Ultra-G-Fest! Official Program Book

OFFICIAL PROGRAM BOOK SEE: AKIRA TAKARADA LINDA MILLER BIN FURUYA HIROKO SAKURAI HIROSHI SAGAE YOSHIKAZU ISHII SOJIRO UCHINO AUGUST RAGONE CARL CRAIG ROBERT SCOTT FIELD ULTRA-G-FEST! G-FEST XXIII PROGRAM, JULY 15 - 17, 2016 G-FEST XXIII PROGRAM, JULY 15 - 17, 2016 TABLE OF WELCOME! As I complete the assembling of CONTENTS this program booklet, the largest yet in G- FEST history, I am amazed at the depth and variety of all that our annual gathering of Godzilla fans offers. For starters, it seems to Welcome...................................................................3 me that the programming schedule is so packed with interesting sessions that it will be difficult to choose which ones to attend Special guests and presenters.........................4, 5 and which ones to miss. Like the program book, the list of people participating in the convention in an Map of G-FEST rooms..........................................6 “official” capacity is the largest ever. This tells me that more people are seeing G-FEST as not just a place to The Dealer Room...................................................7 have fun and take in what’s on offer, but also to offer something themselves. Becoming a participant in the many activities that take place over the weekend is an excellent way to make the experience Daily schedule of events................................8 - 10 even better and more memorable. And of course, there are many, many things to do. G-FEST is distinguished from most other shows in that, while shopping for Descriptions of informational sessions.......11- 13 collectibles and obtaining autographs are important for many attendees, they are balanced by several other equally strong facets. -

From Atomic Allegory to King of the Monsters: an Exploration of Godzilla’S Shifts in Identity Over the Past Six Decades

Institute of Art, Design & Technology, Dun Laoghaire. Faculty of Film, Art & Creative Technologies. Saoirse Whelan Design for Stage and Screen From Atomic Allegory to King of the Monsters: An Exploration of Godzilla’s Shifts in Identity Over the Past Six Decades Submitted to the Department of Design and Visual Arts in candidacy for the Bachelor of Arts (Hons) Design for Stage and Screen Faculty of Film Art and Creative Technologies 2020 This dissertation is submitted by the undersigned to the Institute of Art Design and Technology, Dun Laoghaire in partial fulfilment for the BA (Hons) in Design for Stage and Screen. It is entirely the author’s own work, except where noted, and has not been submitted for an award from this or any other educational institution. Signed: Saoirse Whelan 2 Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank Dr Alice Rekab for their invaluable insights and guidance throughout this process. I would also like to thank Dr Elaine Sisson for her expertise, support and thoughtful feedback over the last three and a half years. Lastly, I would like to thank my friends and family for their continuous support throughout the research and writing process. 3 Abstract In a global post-war environment, people were looking for an outlet for their trauma while not upsetting the delicate status quo that had been achieved at the end of World War II. The war ended in 1945 when Japan became the first and last country to experience the devastation of the atomic bomb forcing them to surrender unconditionally. The atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima alone killed 70000 in the initial blast and countless more in the months following the blast due to acute radiation sickness and radiation-related illnesses. -

WCBR'scountry

Notes from the WCBR Residents’ Association July marks the beginning of the year for Meetings are being held electronically, the WCBR Residents’ Association (RA). It conversations are taking place safely, and goes without saying that this is one of the role of the RA is as strong as ever. the most challenging periods of our time Priority issues for us are: as we find ourselves in the midst of the worldwide COVID-19 Pandemic. In response, Emerging safely from some of our we have been well led by our Administration restrictions to a phased reopening — a and supported by our talented and caring new normal for the foreseeable future. Associates. Our collective care for each Addressing issues in our care areas. other and our patience and forbearance have kept us safe as we have adhered Relieving the burdens of our isolation to the quarantine and lockdown restrictions. as we continue this restricted period. In beginning the new year, the overriding Your comments and questions are welcome; reality is that the virus is spreading, your participation and support appreciated. not receding, either locally or nationally. WCBR is a community that continues to WCBR’s recent experience of few incidents serve and be served. can only be sustained with our continued Please wear a mask, maintain a 6-foot adherence to the best practices we have distance, and wash your hands. learned and are now observing. Stay safe, In this new reality, I am happy to report that the WCBR RA is actively engaged and Charlie Stamm addressing their respective areas of interest. -

Download Download

TiTan of Terror A Personification of the Destroyer of Worlds alessandra luedekIng In 1954, Japan was barely recoverIng from a devastatIng defeat In world war II and a humIlIatIng seven-year amerIcan occupatIon when the unIted states dropped two atomIc bombs over hIroshIma and nagasakI. plunged Into the atomIc age, Japan produced a fIlm, Gojira (godzIlla), that reflected the psychologIcal trauma of a people tryIng to salvage theIr cItIes, theIr culture, and theIr lIves. In the fIlm, the monster Is the physIcal embodIment of the destructIve forces of nuclear power. Its poIgnancy Is derIved from Its hIstorIcal allusIons to real events, IncludIng the Lucky DraGon 5 IncIdent In whIch a Japanese tuna trawler was covered In radIoactIve ash from the detonatIon of an underwater amerIcan atom bomb. moreover, the fIlm captures the conflIct between censorshIp of athe exposItIon of truth, focusIng on the burden of scIentIfIc responsIbIlIty. fInally, the fIlm concludes by underscorIng the ultImate vIctImIzatIon of humanIty under the tyranny of massIve destructIon and warns agaInst the perIls of nuclear prolIferatIon. The attack on the United States at Pearl Harbor by the Japanese were denied the ability to reflect on the meaning Japanese Imperial Navy “provoked a rage bordering on the of nuclear weapons and their impact on the nation. genocidal among Americans.” It prompted “exterminatio- nist rhetoric” that reflected deep-seated anti-Oriental That is, until Gojira appeared. The film, directed by Ishira sentiment, including Admiral William Halsey’s Honda, provided the psychological outlet to externalize the motivational slogan, “Kill Japs, kill Japs, kill more Japs” fears of nuclear annihilation and the attempts of a people and the popular wartime phrase, “the only good Jap is a to rebuild their cities, their culture, and their lives, 84 dead Jap.”1 The Japanese were pejoratively referred to as threatened by radioactive fallout.