(NCCN Guidelines®) Neuroendocrine Tumors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: Report of Two Cases and Literature Review

The Jackson Laboratory The Mouseion at the JAXlibrary Faculty Research 2018 Faculty Research 3-1-2018 Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: report of two cases and literature review. Zi-Ming Zhao The Jackson Laboratory, [email protected] Jin Wang Ugochukwu C Ugwuowo Liming Wang Jeffrey P Townsend Follow this and additional works at: https://mouseion.jax.org/stfb2018 Part of the Life Sciences Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Zhao, Zi-Ming; Wang, Jin; Ugwuowo, Ugochukwu C; Wang, Liming; and Townsend, Jeffrey P, "Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: report of two cases and literature review." (2018). Faculty Research 2018. 71. https://mouseion.jax.org/stfb2018/71 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Research at The ousM eion at the JAXlibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research 2018 by an authorized administrator of The ousM eion at the JAXlibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zhao et al. BMC Clinical Pathology (2018) 18:3 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12907-018-0070-7 CASE REPORT Open Access Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: report of two cases and literature review Zi-Ming Zhao1,2*† , Jin Wang3,4,5†, Ugochukwu C. Ugwuowo6, Liming Wang4,8* and Jeffrey P. Townsend2,7* Abstract Background: Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (PHNEC) is extremely rare. The diagnosis of PHNEC remains challenging—partly due to its rarity, and partly due to its lack of unique clinical features. Available treatment options for PHNEC include surgical resection of the liver tumor(s), radiotherapy, liver transplant, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), and administration of somatostatin analogues. -

What Is a Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumor?

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 About Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors Overview and Types If you have been diagnosed with a gastrointestinal carcinoid tumor or are worried about it, you likely have a lot of questions. Learning some basics is a good place to start. ● What Is a Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumor? Research and Statistics See the latest estimates for new cases of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumor in the US and what research is currently being done. ● Key Statistics About Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors ● What’s New in Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumor Research? What Is a Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumor? Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors are a type of cancer that forms in the lining of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Cancer starts when cells begin to grow out of control. To learn more about what cancer is and how it can grow and spread, see What Is Cancer?1 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 To understand gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors, it helps to know about the gastrointestinal system, as well as the neuroendocrine system. The gastrointestinal system The gastrointestinal (GI) system, also known as the digestive system, processes food for energy and rids the body of solid waste. After food is chewed and swallowed, it enters the esophagus. This tube carries food through the neck and chest to the stomach. The esophagus joins the stomachjust beneath the diaphragm (the breathing muscle under the lungs). The stomach is a sac that holds food and begins the digestive process by secreting gastric juice. The food and gastric juices are mixed into a thick fluid, which then empties into the small intestine. -

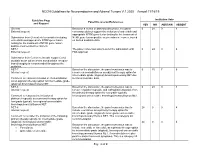

NCCN Guidelines for Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors V.1.2020 – Annual 11/18/19

NCCN Guidelines for Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors V.1.2020 – Annual 11/18/19 Guideline Page Institution Vote Panel Discussion/References and Request YES NO ABSTAIN ABSENT General Based on a review of data and discussion, the panel 0 24 0 4 External request: consensus did not support the inclusion of entrectinib and appropriate NTRK gene fusion testing for the treatment of Submission from Genentech to consider including NTRK gene fusion-positive neuroendocrine cancer, based entrectinib and appropriate NTRK gene fusion on limited available data. testing for the treatment of NTRK gene fusion- positive neuroendocrine cancers. NET-1 The panel consensus was to defer the submission until 0 24 0 4 External request: FDA approval. Submission from Curium to include copper Cu 64 dotatate as an option where somatostatin receptor- based imaging is recommended throughout the guideline. NET-7 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 0 15 7 6 Internal request: remove chemoradiation as an adjuvant therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical) bronchopulmonary NET due Comment to reassess inclusion of chemoradiation to limited available data. as an adjuvant therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical) bronchopulmonary NET. NET-8 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 0 24 0 4 Internal request: remove cisplatin/etoposide and carboplatin/etoposide from the primary therapy option for low grade (typical), Comment to reassess the inclusion of locoregional unresectable bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. platinum/etoposide as a primary therapy option for low grade (typical), locoregional unresectable bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. NET-8 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 24 0 0 4 Internal request: include everolimus as a primary therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical), locoregional unresectable Comment to consider the inclusion of the following bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. -

Rising Incidence of Neuroendocrine Tumors

Rising Incidence of Neuroendocrine Tumors Dasari V, Yao J, et al. JAMA Oncology 2017 S L I D E 1 Overview Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors • Tumors which arise from endocrine cells of the pancreas • 5.6 cases per million – 3% of pancreatic tumors • Median age at diagnosis 60 years • More indolent course compared to adenocarcinoma – 10-year overall survival 40% • Usually sporadic but can be associated with hereditary syndromes – Core genetic pathways altered in sporadic cases • DNA damage repair (MUTYH) Chromatin remodeling (MEN1) • Telomere maintenance (MEN1, DAXX, ATRX) mTOR signaling – Hereditary: 17% of patients with germline mutation Li X, Wang C, et al. Cancer Med 2018 Scarpa A, Grimond S, et al. NatureS L I2017 D E 2 Pathology Classification European American Joint World Health Organization Neuroendocrine Committee on Cancer (WHO) Tumor Society (AJCC) (ENETS) Grade Ki-67 Mitotic rt TNM TNM T1: limit to pancreas, <2 cm T1: limit to pancreas, ≦2 cm T2: limit to pancreas, 2-4 cm T2: >limit to pancreas, 2 cm T3: limit to pancreas, >4 cm, T3: beyond pancreas, no celiac or Low ≤2% <2 invades duodenum, bile duct SMA T4: beyond pancreas, invasion involvement adjacent organs or vessels T4: involves celiac or SMA N0: node negative No: node negative Intermed 3-20% 2-20 N1: node positive N1: node positive M0: no metastases M0: no metastases High >20% >20 M1: metastases M1: metastases S L I D E 3 Classification Based on Functionality • Nonfunctioning tumors – No clinical symptoms (can still produce hormone) – Accounts for 40% of tumors – 60-85% -

Primary Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Kidney, a Distinct Entity but Classifiable- Like the Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms

C-60 Primary Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Kidney, A Distinct Entity but Classifiable- Like the Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms Manik Amin1; Deyali Chatterjee2 1Washington University in St Louis; 2Washington University School of Medicine BACKGROUND: Primary neuroendocrine neoplasms of the kidney are a distinct and rare entity, but classifiable-like the gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Due to rarity of these tumors, not much is known about histopathology and behaviors of these tumors. We attempted to review pathology of primary kidney neuroendocrine tumor patients at our institution. METHODS: Retrospective chart review identified 8 primary kidney neuroendocrine tumors from Siteman Cancer Registry database from 1/1/2000 until 1/1/2018. Pathology review was done for all the patients to confirm their diagnosis and other pathological features. RESULTS: In our cohort, we identified eight cases of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the kidney. Three of the cases were poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma. All cases of well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (either grade 1 or grade 2) were identified in females (age range 44 – 60). All the tumors characteristically extended to the perirenal fat. These tumors showed diffuse positivity for synaptophysin, variable positivity for chromogranin, and did not stain for markers specific for renal differentiation (PAX-8). The growth pattern in well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors is predominantly trabeculated, but a diffuse plasmacytoid growth is also noted, which is unusual in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Two patients had Primary tumor measuring 9 cm and 14 cm respectively also presented with positive lymph nodes and lymphovascular invasion developed metastatic disease in 2 years. NANETS 2019 Symposium Abstracts | 175 CONCLUSION: Primary kidney neuroendocrine tumors are very rare. -

Solitary Duodenal Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma with Metachronous Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: Review of Literature with a Case Discussion

Published online: 2021-05-24 Practitioner Section Solitary Duodenal Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma with Metachronous Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: Review of Literature with a Case Discussion Abstract Saphalta Baghmar, Renal cell cancinoma (RCC) is a unique malignancy with features of late recurrences, metastasis S M Shasthry1, to any organ, and frequent association with second malignancy. It most commonly metastasizes Rajesh Singla, to the lungs, bones, liver, renal fossa, and brain although metastases can occur anywhere. RCC 2 metastatic to the duodenum is especially rare, with only few cases reported in the literature. Herein, Yashwant Patidar , 3 we review literature of all the reported cases of solitary duodenal metastasis from RCC and cases Chhagan B Bihari , of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) as synchronous/metachronous malignancy with RCC. Along with S K Sarin1 this, we have described a unique case of an 84‑year‑old man who had recurrence of RCC as solitary Departments of Medical duodenal metastasis after 37 years of radical nephrectomy and metachronous pancreatic NET. Oncology, 1Hepatology, 2Radiology and 3Pathology, Keywords: Late recurrence, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, renal cell carcinoma, second Institute of Liver and Biliary malignancy, solitary duodenal metastasis Sciences, New Delhi, India Introduction Case Presentation Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is unique An 84‑year‑old man with a medical history to have many unusual features such as notable for hypertension and RCC, 37 years metastasis to almost every organ in the body, postright radical nephrectomy status, late recurrences, and frequent association presented to his primary care physician with second malignancy. The most common with fatigue. When found to be anemic, sites of metastasis are the lung, lymph he was treated with iron supplementation nodes, liver, bone, adrenal glands, kidney, and blood transfusions. -

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1: the Potential Role of Micrornas in the Management of the Syndrome

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1: The Potential Role of microRNAs in the Management of the Syndrome Simone Donati 1, Simone Ciuffi 1 , Francesca Marini 1, Gaia Palmini 1 , Francesca Miglietta 1, Cinzia Aurilia 1 and Maria Luisa Brandi 1,2,3,* 1 Department of Experimental and Clinical Biomedical Sciences “Mario Serio”, University of Study of Florence, Viale Pieraccini 6, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected] (S.D.); simone.ciuffi@unifi.it (S.C.); francesca.marini@unifi.it (F.M.); gaia.palmini@unifi.it (G.P.); [email protected] (F.M.); [email protected] (C.A.) 2 Unit of Bone and Mineral Diseases, University Hospital of Florence, Largo Palagi 1, 50139 Florence, Italy 3 Fondazione Italiana Ricerca Sulle Malattie Dell’Osso (FIRMO Onlus), 50141 Florence, Italy * Correspondence: marialuisa.brandi@unifi.it; Tel.: +39-055-7946304 Received: 24 September 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020; Published: 14 October 2020 Abstract: Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is a rare inherited tumor syndrome, characterized by the development of multiple neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in a single patient. Major manifestations include primary hyperparathyroidism, gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, and pituitary adenomas. In addition to these main NETs, various combinations of more than 20 endocrine and non-endocrine tumors have been described in MEN1 patients. Despite advances in diagnostic techniques and treatment options, which are generally similar to those of sporadic tumors, patients with MEN1 have a poor life expectancy, and the need for targeted therapies is strongly felt. MEN1 is caused by germline heterozygous inactivating mutations of the MEN1 gene, which encodes menin, a tumor suppressor protein. -

Recurrence of a Neuroendocrine Tumor of Adrenal Origin: a Case

Rahmani et al. BMC Endocrine Disorders (2021) 21:9 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00673-7 CASE REPORT Open Access Recurrence of a neuroendocrine tumor of adrenal origin: a case report with more than a decade follow-up Fatemeh Rahmani1, Maryam Tohidi1, Maryam Dehghani1, Behrooz Broumand2 and Farzad Hadaegh1* Abstract Background: Neuroendocrine tumor (NET) with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion are very rare. To our knowledge, no follow-up study is published for ACTH-secreting NET, regardless of the primary site, to show second occurrence of tumor after a long follow-up, following resection of primary tumor. Case presentation: Here, we describe a 49-year-old-man with cushingoid feature, drowsiness and quadriparesis came to emergency department at December 2005. Laboratory tests revealed hyperglycemia, metabolic alkalosis, severe hypokalemia, and chemical evidence of an ACTH-dependent hypercortisolism as morning serum cortisol of 57 μg/dL without suppression after 8 mg dexamethasone suppression test, serum ACTH level of 256 pg/mL, and urine free cortisol of > 1000 μg /24 h. Imaging showed only bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, without evidence of pituitary adenoma or ectopic ACTH producing tumors. Importantly, other diagnostic tests for differentiating Cushing disease (CD) from ectopic ACTH producing tumor, such as inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS), corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) stimulation test, octreotide scan or fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) scan were not available in our country at that time. Therefore, bilateral adrenalectomy was performed that led to clinical and biochemical remission of hypercortisolism and decreased ACTH level to < 50 pg/mL, findings suggestive of a primary focus of NET in adrenal glands. -

Well Differentiated Grade 3 Neuroendocrine Tumors Of

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Well Differentiated Grade 3 Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Digestive Tract: A Narrative Review Anna Pellat 1,2,3,* and Romain Coriat 1,2 1 Department of Gastroenterology and digestive oncology, Cochin Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, 75014 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 Faculté de Médecine, Université de Paris, 75006 Paris, France 3 Oncology Unit, Hôpital Saint Antoine, AP-HP, Sorbonne Université, 75012 Paris, France * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33(0)1-4928-2336; Fax: +33(0)1-4928-3498 Received: 18 April 2020; Accepted: 28 May 2020; Published: 1 June 2020 Abstract: The 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN) of the digestive tract introduced a new category of tumors named well-differentiated grade 3 neuroendocrine tumors (NET G 3). These lesions show a number of mitosis, or a Ki 67 index higher − − than 20% with a well-differentiated morphology, therefore separating them from neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC) which are poorly differentiated. It has become clear that NET G 3 show differences − not only in morphology but also in genotype, clinical presentation, and treatment response. The incidence of digestive NET G 3 represents about one third of NEN G 3 with main tumor sites being − − the pancreas, the stomach and the colon. Treatment for NET G 3 is not yet standardized because − of lack of data. In a non-metastatic setting, international guidelines recommend surgical resection, regardless of tumor grading. For metastatic lesion, chemotherapy is the main treatment with similar regimen as NET G 2. Sunitinib has also shown some positive results in a small sample of patients but − this needs confirmation. -

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Carinne W. Anderson, MD*, Joseph J. Bennett, MD KEYWORDS Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor Nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor Insulinoma Gastrinoma Glucagonoma VIPoma Somatostatinoma KEY POINTS Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are a rare group of neoplasms, most of which are nonfunctioning. Functional pancreatic neoplasms secrete hormones that produce unique clinical syndromes. The key management of these rare tumors is to first suspect the diagnosis; to do this, cli- nicians must be familiar with their clinical syndromes. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are a rare group of neoplasms that arise from multipotent stem cells in the pancreatic ductal epithelium. Most PNETs are nonfunctioning, but they can secrete various hormones resulting in unique clinical syn- dromes. Clinicians must be aware of the diverse manifestations of this disease, as the key step to management of these rare tumors is to first suspect the diagnosis. In light of that, this article focuses on the clinical features of different PNETs. Surgical and medical management will not be discussed here, as they are addressed in other arti- cles in this issue. EPIDEMIOLOGY Classification PNETs are classified clinically as nonfunctional or functional, based on the properties of the hormones they secrete and their ability to produce a clinical syndrome. Nonfunctional PNETs (NF-PNETs) do not produce a clinical syndrome simply because they do not secrete hormones or because the hormones that are secreted do not The authors have nothing to disclose. Department of Surgery, Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, 4701 Ogletown-Stanton Road, S-4000, Newark, DE 19713, USA * Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] Surg Oncol Clin N Am 25 (2016) 363–374 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2015.12.003 surgonc.theclinics.com 1055-3207/16/$ – see front matter Ó 2016 Elsevier Inc. -

Neuroendocrine Tumor V1-907-4109.0.Indd

IHC PANEL MARKERS Neuroendocrine Tumor BioGenex offers wide-ranging antibodies for several IHC panel for initial differentiation, tumor origin, treatment methods, and prognosis. All BioGenex antibodies are validated on human tissues to ensure sensitivity and specificity. BioGenex comprehensive IHC panels include a range of mouse monoclonal, rabbit monoclonal, and polyclonal antibodies to choose from. BioGenex offers a vast spectrum of high-quality antibodies for both diagnostic and reference laboratories. BioGenex strives to support efforts in clinical diagnostics and drug discovery development as we continue to expand our antibody product line offering in both ready-to-use and concentrated formats for both manual and automation systems. Antibodies for Neuroendocrine Tumor PGP9.5, IDH1, Chromogranin A, Ki-67, NKX3.1, Synaptophysin, Chromogranin A, Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) Beta, HCGα, Glucagon, Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP), VIP, FSH-BETA, Inhibin-Alpha, Neurofilament, CD56, NSE, CDX2, TTF1, GFAP, Prolactin, Ki-67, LH, CD57, NSE NEW IHC PANEL MARKERS - Neuroendocrine Tumor PGP9.5 This antibody reacts with a protein of 20-30kDa, identified as PGP9.5, also known as ubiquitin UchL1. PGP9.5 is highly expressed in neurons and to cells of the diffuse neuroendocrine system and their tumors. It is abundantly present in all neurons (accounts for 1-2% of total brain protein), expressed specifically in neurons and testis/ovary.[5][6] Although UCH-L1 protein expression is specific to neurons and testis/ovary tissue, it has been found to be expressed in certain lung-tumor cell lines.[16] This abnormal expression of UCH-L1 is implicated in cancer and has led to the designation of UCH-L1 as an oncogene.[17] Furthermore, immunostaining for PGP9.5 has been shown in a wide variety of mesenchymal neoplasms as well. -

Differences Between Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Differences between Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors and Ductal Adenocarcinomas of the Pancreas Assessed by Multi-Omics Profiling 1, 2, 2,3 2,3 Teresa Starzy ´nska y, Jakub Karczmarski y, Agnieszka Paziewska , Maria Kulecka , Katarzyna Ku´snierz 4 , Natalia Zeber-Lubecka˙ 3, Filip Ambro˙zkiewicz 2 , Michał Mikula 2 , Beata Kos-Kudła 5 and Jerzy Ostrowski 2,3,* 1 Department of Gastroenterology, Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, 70-204 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Genetics, Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, 02-781 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (M.K.); fi[email protected] (F.A.); [email protected] (M.M.) 3 Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Clinical Oncology, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, 01-813 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] 4 Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Medical University of Silesia, 40-514 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] 5 Department of Endocrinology and Neuroendocrine Tumors, ENETS Center of Excelence, Department of Pathophysiology and Endocrinology, Medical University of Silesia, 40-514 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-225462575; Fax: +48-225462449 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 18 May 2020; Accepted: 18 June 2020; Published: 23 June 2020 Abstract: Most pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are indolent, while pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs) are particularly aggressive. To elucidate the basis for this difference and to establish the biomarkers, by using the deep sequencing, we analyzed somatic variants across coding regions of 409 cancer genes and measured mRNA/miRNA expression in nine PNETs, eight PDACs, and four intestinal neuroendocrine tumors (INETs).