Challenges in Treatment of a Patient Suffering from Neuroendocrine Tumor G1 of the Hilar Bile Duct: a Case Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klatskin Tumors and “Klatskin-Mimicking Lesions”: Our 22- Year Experience

Title: Klatskin tumors and “Klatskin-mimicking lesions”: our 22- year experience. Authors: Konstantinos Tsalis, Styliani Parpoudi, Dimitrios Kyziridis, Orestis Ioannidis, Natalia Antigoni Savvala, Nikolaos Antoniou, Savvas Symeonidis, Dimitrios Konstantaras, Ioannis Mantzoros, Manousos-Georgios Pramateftakis, Efstathios Kotidis, Stamatios Angelopoulos DOI: 10.17235/reed.2018.5749/2018 Link: PubMed (Epub ahead of print) Please cite this article as: Tsalis Konstantinos, Parpoudi Styliani, Kyziridis Dimitrios, Ioannidis Orestis, Savvala Natalia Antigoni , Antoniou Nikolaos , Symeonidis Savvas, Konstantaras Dimitrios , Mantzoros Ioannis, Pramateftakis Manousos-Georgios, Kotidis Efstathios, Angelopoulos Stamatios. Klatskin tumors and “Klatskin-mimicking lesions”: our 22-year experience. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2018. doi: 10.17235/reed.2018.5749/2018. This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. OR 5749 Klatskin tumors and “Klatskin-mimicking lesions”: our 22-year experience Konstantinos Tsalis, Styliani Parpoudi, Dimitrios Kyziridis, Orestis Ioannidis, Natalia Antigoni-Savvala, Nikolaos Antoniou, Savvas Symeonidis, Dimitrios Konstantaras, Ioannis Mantzoros, Pramateftakis Manousos-George, Kotidis Efstathios and Stamatios Angelopoulos Fourth Surgical Department. Medical School. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Thessaloniki, Greece. General Hospital “George Papanikoalou”. Thessaloniki, Greece Received: 04/06/2018 Accepted: 04/09/2018 Correspondence: Orestis Ioannidis. Fourth Surgical Department. Medical School. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Thessaloniki, Greece. General Hospital “G. -

Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: Report of Two Cases and Literature Review

The Jackson Laboratory The Mouseion at the JAXlibrary Faculty Research 2018 Faculty Research 3-1-2018 Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: report of two cases and literature review. Zi-Ming Zhao The Jackson Laboratory, [email protected] Jin Wang Ugochukwu C Ugwuowo Liming Wang Jeffrey P Townsend Follow this and additional works at: https://mouseion.jax.org/stfb2018 Part of the Life Sciences Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Zhao, Zi-Ming; Wang, Jin; Ugwuowo, Ugochukwu C; Wang, Liming; and Townsend, Jeffrey P, "Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: report of two cases and literature review." (2018). Faculty Research 2018. 71. https://mouseion.jax.org/stfb2018/71 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Research at The ousM eion at the JAXlibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research 2018 by an authorized administrator of The ousM eion at the JAXlibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zhao et al. BMC Clinical Pathology (2018) 18:3 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12907-018-0070-7 CASE REPORT Open Access Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: report of two cases and literature review Zi-Ming Zhao1,2*† , Jin Wang3,4,5†, Ugochukwu C. Ugwuowo6, Liming Wang4,8* and Jeffrey P. Townsend2,7* Abstract Background: Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (PHNEC) is extremely rare. The diagnosis of PHNEC remains challenging—partly due to its rarity, and partly due to its lack of unique clinical features. Available treatment options for PHNEC include surgical resection of the liver tumor(s), radiotherapy, liver transplant, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), and administration of somatostatin analogues. -

What Is a Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumor?

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 About Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors Overview and Types If you have been diagnosed with a gastrointestinal carcinoid tumor or are worried about it, you likely have a lot of questions. Learning some basics is a good place to start. ● What Is a Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumor? Research and Statistics See the latest estimates for new cases of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumor in the US and what research is currently being done. ● Key Statistics About Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors ● What’s New in Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumor Research? What Is a Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumor? Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors are a type of cancer that forms in the lining of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Cancer starts when cells begin to grow out of control. To learn more about what cancer is and how it can grow and spread, see What Is Cancer?1 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 To understand gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors, it helps to know about the gastrointestinal system, as well as the neuroendocrine system. The gastrointestinal system The gastrointestinal (GI) system, also known as the digestive system, processes food for energy and rids the body of solid waste. After food is chewed and swallowed, it enters the esophagus. This tube carries food through the neck and chest to the stomach. The esophagus joins the stomachjust beneath the diaphragm (the breathing muscle under the lungs). The stomach is a sac that holds food and begins the digestive process by secreting gastric juice. The food and gastric juices are mixed into a thick fluid, which then empties into the small intestine. -

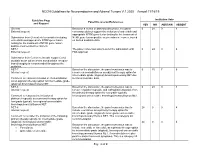

NCCN Guidelines for Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors V.1.2020 – Annual 11/18/19

NCCN Guidelines for Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors V.1.2020 – Annual 11/18/19 Guideline Page Institution Vote Panel Discussion/References and Request YES NO ABSTAIN ABSENT General Based on a review of data and discussion, the panel 0 24 0 4 External request: consensus did not support the inclusion of entrectinib and appropriate NTRK gene fusion testing for the treatment of Submission from Genentech to consider including NTRK gene fusion-positive neuroendocrine cancer, based entrectinib and appropriate NTRK gene fusion on limited available data. testing for the treatment of NTRK gene fusion- positive neuroendocrine cancers. NET-1 The panel consensus was to defer the submission until 0 24 0 4 External request: FDA approval. Submission from Curium to include copper Cu 64 dotatate as an option where somatostatin receptor- based imaging is recommended throughout the guideline. NET-7 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 0 15 7 6 Internal request: remove chemoradiation as an adjuvant therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical) bronchopulmonary NET due Comment to reassess inclusion of chemoradiation to limited available data. as an adjuvant therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical) bronchopulmonary NET. NET-8 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 0 24 0 4 Internal request: remove cisplatin/etoposide and carboplatin/etoposide from the primary therapy option for low grade (typical), Comment to reassess the inclusion of locoregional unresectable bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. platinum/etoposide as a primary therapy option for low grade (typical), locoregional unresectable bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. NET-8 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 24 0 0 4 Internal request: include everolimus as a primary therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical), locoregional unresectable Comment to consider the inclusion of the following bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. -

Case Report Primary Neuroendocrine Tumor of the Left Hepatic Duct: a Case Report with Review of the Literature

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Surgery Volume 2012, Article ID 786432, 7 pages doi:10.1155/2012/786432 Case Report Primary Neuroendocrine Tumor of the Left Hepatic Duct: A Case Report with Review of the Literature Ajay H. Bhandarwar, Taher A. Shaikh, Ashok D. Borisa, Jaydeep H. Palep, Arun S. Patil, and Aditya A. Manke Division of GI and HPP Surgery, Department of Surgery, Grant Medical College & Sir JJ Group of Hospitals, Byculla, Mumbai 400008, India Correspondence should be addressed to Ajay H. Bhandarwar, [email protected] Received 29 April 2012; Accepted 29 August 2012 Academic Editors: T. C¸ olak and M. Ganau Copyright © 2012 Ajay H. Bhandarwar et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Primary Biliary Tract Neuroendocrine tumors (NET) are extremely rare tumors with only 77 cases been reported in the literature till now. We describe a case of a left hepatic duct NET and review the literature for this rare malignancy. To the best of our knowledge the present case is the first reported case of a left hepatic duct NET in the literature. In spite of availability of advanced diagnostic tools like Computerized Tomography (CT) Scan and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio Pancreaticography (ERCP) a definitive diagnosis of these tumors is possible only after an accurate histopathologic diagnosis of operative specimens with immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy. Though surgical excision remains the gold standard treatment for such tumors, patients with unresectable tumors have good survival with newer biologic agents like Octreotride. -

Rising Incidence of Neuroendocrine Tumors

Rising Incidence of Neuroendocrine Tumors Dasari V, Yao J, et al. JAMA Oncology 2017 S L I D E 1 Overview Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors • Tumors which arise from endocrine cells of the pancreas • 5.6 cases per million – 3% of pancreatic tumors • Median age at diagnosis 60 years • More indolent course compared to adenocarcinoma – 10-year overall survival 40% • Usually sporadic but can be associated with hereditary syndromes – Core genetic pathways altered in sporadic cases • DNA damage repair (MUTYH) Chromatin remodeling (MEN1) • Telomere maintenance (MEN1, DAXX, ATRX) mTOR signaling – Hereditary: 17% of patients with germline mutation Li X, Wang C, et al. Cancer Med 2018 Scarpa A, Grimond S, et al. NatureS L I2017 D E 2 Pathology Classification European American Joint World Health Organization Neuroendocrine Committee on Cancer (WHO) Tumor Society (AJCC) (ENETS) Grade Ki-67 Mitotic rt TNM TNM T1: limit to pancreas, <2 cm T1: limit to pancreas, ≦2 cm T2: limit to pancreas, 2-4 cm T2: >limit to pancreas, 2 cm T3: limit to pancreas, >4 cm, T3: beyond pancreas, no celiac or Low ≤2% <2 invades duodenum, bile duct SMA T4: beyond pancreas, invasion involvement adjacent organs or vessels T4: involves celiac or SMA N0: node negative No: node negative Intermed 3-20% 2-20 N1: node positive N1: node positive M0: no metastases M0: no metastases High >20% >20 M1: metastases M1: metastases S L I D E 3 Classification Based on Functionality • Nonfunctioning tumors – No clinical symptoms (can still produce hormone) – Accounts for 40% of tumors – 60-85% -

NCCN Guidelines for Patients Gallbladder and Bile Duct Cancers

NCCN GUIDELINES FOR PATIENTS® 2021 Gallbladder and Bile Duct Cancers Hepatobiliary Cancers Presented with support from: Available online at NCCN.org/patients Ü Gallbladder and Bile Duct Cancers It's easy to get lost in the cancer world Let Ü NCCN Guidelines for Patients® be your guide 9 Step-by-step guides to the cancer care options likely to have the best results 9 Based on treatment guidelines used by health care providers worldwide 9 Designed to help you discuss cancer treatment with your doctors NCCN Guidelines for Patients® Gallbladder and Bile Duct Cancers, 2021 1 About National Comprehensive Cancer Network® NCCN Guidelines for Patients® are developed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) NCCN Clinical Practice NCCN Guidelines NCCN Ü Ü Guidelines in Oncology for Patients (NCCN Guidelines®) 9 An alliance of leading 9 Developed by doctors from 9 Present information from the cancer centers across the NCCN cancer centers using NCCN Guidelines in an easy- United States devoted to the latest research and years to-learn format patient care, research, and of experience 9 For people with cancer and education 9 For providers of cancer care those who support them all over the world Cancer centers 9 Explain the cancer care that are part of NCCN: 9 Expert recommendations for options likely to have the NCCN.org/cancercenters cancer screening, diagnosis, best results and treatment Free online at Free online at NCCN.org/patientguidelines NCCN.org/guidelines and supported by funding from NCCN Foundation® These NCCN Guidelines for Patients are based on the NCCN Guidelines® for Hepatobiliary Cancers (Version 3.2021, June 15, 2021). -

Primary Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Kidney, a Distinct Entity but Classifiable- Like the Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms

C-60 Primary Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Kidney, A Distinct Entity but Classifiable- Like the Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms Manik Amin1; Deyali Chatterjee2 1Washington University in St Louis; 2Washington University School of Medicine BACKGROUND: Primary neuroendocrine neoplasms of the kidney are a distinct and rare entity, but classifiable-like the gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Due to rarity of these tumors, not much is known about histopathology and behaviors of these tumors. We attempted to review pathology of primary kidney neuroendocrine tumor patients at our institution. METHODS: Retrospective chart review identified 8 primary kidney neuroendocrine tumors from Siteman Cancer Registry database from 1/1/2000 until 1/1/2018. Pathology review was done for all the patients to confirm their diagnosis and other pathological features. RESULTS: In our cohort, we identified eight cases of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the kidney. Three of the cases were poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma. All cases of well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (either grade 1 or grade 2) were identified in females (age range 44 – 60). All the tumors characteristically extended to the perirenal fat. These tumors showed diffuse positivity for synaptophysin, variable positivity for chromogranin, and did not stain for markers specific for renal differentiation (PAX-8). The growth pattern in well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors is predominantly trabeculated, but a diffuse plasmacytoid growth is also noted, which is unusual in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Two patients had Primary tumor measuring 9 cm and 14 cm respectively also presented with positive lymph nodes and lymphovascular invasion developed metastatic disease in 2 years. NANETS 2019 Symposium Abstracts | 175 CONCLUSION: Primary kidney neuroendocrine tumors are very rare. -

New Jersey State Cancer Registry List of Reportable Diseases and Conditions Effective Date March 10, 2011; Revised March 2019

New Jersey State Cancer Registry List of reportable diseases and conditions Effective date March 10, 2011; Revised March 2019 General Rules for Reportability (a) If a diagnosis includes any of the following words, every New Jersey health care facility, physician, dentist, other health care provider or independent clinical laboratory shall report the case to the Department in accordance with the provisions of N.J.A.C. 8:57A. Cancer; Carcinoma; Adenocarcinoma; Carcinoid tumor; Leukemia; Lymphoma; Malignant; and/or Sarcoma (b) Every New Jersey health care facility, physician, dentist, other health care provider or independent clinical laboratory shall report any case having a diagnosis listed at (g) below and which contains any of the following terms in the final diagnosis to the Department in accordance with the provisions of N.J.A.C. 8:57A. Apparent(ly); Appears; Compatible/Compatible with; Consistent with; Favors; Malignant appearing; Most likely; Presumed; Probable; Suspect(ed); Suspicious (for); and/or Typical (of) (c) Basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin are NOT reportable, except when they are diagnosed in the labia, clitoris, vulva, prepuce, penis or scrotum. (d) Carcinoma in situ of the cervix and/or cervical squamous intraepithelial neoplasia III (CIN III) are NOT reportable. (e) Insofar as soft tissue tumors can arise in almost any body site, the primary site of the soft tissue tumor shall also be examined for any questionable neoplasm. NJSCR REPORTABILITY LIST – 2019 1 (f) If any uncertainty regarding the reporting of a particular case exists, the health care facility, physician, dentist, other health care provider or independent clinical laboratory shall contact the Department for guidance at (609) 633‐0500 or view information on the following website http://www.nj.gov/health/ces/njscr.shtml. -

Solitary Duodenal Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma with Metachronous Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: Review of Literature with a Case Discussion

Published online: 2021-05-24 Practitioner Section Solitary Duodenal Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma with Metachronous Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: Review of Literature with a Case Discussion Abstract Saphalta Baghmar, Renal cell cancinoma (RCC) is a unique malignancy with features of late recurrences, metastasis S M Shasthry1, to any organ, and frequent association with second malignancy. It most commonly metastasizes Rajesh Singla, to the lungs, bones, liver, renal fossa, and brain although metastases can occur anywhere. RCC 2 metastatic to the duodenum is especially rare, with only few cases reported in the literature. Herein, Yashwant Patidar , 3 we review literature of all the reported cases of solitary duodenal metastasis from RCC and cases Chhagan B Bihari , of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) as synchronous/metachronous malignancy with RCC. Along with S K Sarin1 this, we have described a unique case of an 84‑year‑old man who had recurrence of RCC as solitary Departments of Medical duodenal metastasis after 37 years of radical nephrectomy and metachronous pancreatic NET. Oncology, 1Hepatology, 2Radiology and 3Pathology, Keywords: Late recurrence, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, renal cell carcinoma, second Institute of Liver and Biliary malignancy, solitary duodenal metastasis Sciences, New Delhi, India Introduction Case Presentation Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is unique An 84‑year‑old man with a medical history to have many unusual features such as notable for hypertension and RCC, 37 years metastasis to almost every organ in the body, postright radical nephrectomy status, late recurrences, and frequent association presented to his primary care physician with second malignancy. The most common with fatigue. When found to be anemic, sites of metastasis are the lung, lymph he was treated with iron supplementation nodes, liver, bone, adrenal glands, kidney, and blood transfusions. -

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

54) BY Prof Dr. Ahmed Al_Gebaly Case 1 54 Male Admitted with distended abdomen and vomiting. Case 2 Patient Data Male 47 years complaining Difficulty in swallowing liquids. Case 3 C/O: Recurrent chest infection Case 4 Axial contrast enhanced CT image of child with jaundice. Case 5 73 year old male with Jaundice Case 1 54 Male Admitted with distended abdomen and vomiting. Grossly distended stomach, containing a large volume of debris. Thickening and enhancement of the anturm/pylorus of the stomach, suggesting of a tumour Stenosing tumour, which caused the gastric outlet obstruction. Biopsy - proven adenocarcinoma. Gastric outlet obstruction is a syndrome resulting from mechanical obstruction of stomach emptying. an be due to malignant or benign causes. Malignant adenocarcinoma (second most common) GIST lymphoma (less commonly than other malignancies as it is a "soft" tumour) metastases Benign duodenal or gastric peptic ulcers (most common) pancreatic pseudocysts gastric varices granulomatous disease, e.g. Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis gallstones (Bouveret's syndrome): rare strictures, e.g. from caustic substance ingestion Gastric adenocarcinoma, commonly referred to as gastric cancer, refers to a primary malignancy arising from the gastric epithelium. It is the most common gastric malignancy (over 95% of malignant tumours of the stomach). Gastric cancer is rare before the age of 40 It often produces no specific symptoms such as dyspepsia. Patients may present with anorexia and weight loss (95%) as well as abdominal pain that is vague and insidious in nature. Nausea and vomiting, may occur (with bulky tumours that obstruct the gastrointestinal lumen or infiltrative lesions that impair stomach distension); late signs. -

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1: the Potential Role of Micrornas in the Management of the Syndrome

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1: The Potential Role of microRNAs in the Management of the Syndrome Simone Donati 1, Simone Ciuffi 1 , Francesca Marini 1, Gaia Palmini 1 , Francesca Miglietta 1, Cinzia Aurilia 1 and Maria Luisa Brandi 1,2,3,* 1 Department of Experimental and Clinical Biomedical Sciences “Mario Serio”, University of Study of Florence, Viale Pieraccini 6, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected] (S.D.); simone.ciuffi@unifi.it (S.C.); francesca.marini@unifi.it (F.M.); gaia.palmini@unifi.it (G.P.); [email protected] (F.M.); [email protected] (C.A.) 2 Unit of Bone and Mineral Diseases, University Hospital of Florence, Largo Palagi 1, 50139 Florence, Italy 3 Fondazione Italiana Ricerca Sulle Malattie Dell’Osso (FIRMO Onlus), 50141 Florence, Italy * Correspondence: marialuisa.brandi@unifi.it; Tel.: +39-055-7946304 Received: 24 September 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020; Published: 14 October 2020 Abstract: Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is a rare inherited tumor syndrome, characterized by the development of multiple neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in a single patient. Major manifestations include primary hyperparathyroidism, gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, and pituitary adenomas. In addition to these main NETs, various combinations of more than 20 endocrine and non-endocrine tumors have been described in MEN1 patients. Despite advances in diagnostic techniques and treatment options, which are generally similar to those of sporadic tumors, patients with MEN1 have a poor life expectancy, and the need for targeted therapies is strongly felt. MEN1 is caused by germline heterozygous inactivating mutations of the MEN1 gene, which encodes menin, a tumor suppressor protein.