Romancing the Pan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explore the Northern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Northern Cape Province When Schalk van Niekerk traded all his possessions for an 83.5 carat stone owned by the Griqua Shepard, Zwartboy, Sir Richard Southey, Colonial Secretary of the Cape, declared with some justification: “This is the rock on which the future of South Africa will be built.” For us, The Star of South Africa, as the gem became known, shines not in the East, but in the Northern Cape. (Tourism Blueprint, 2006) 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Namaqualand Component # 1 - Namaqualand Component # 2 - The Hantam Karoo Component # 3 - Towns along the N14 Component # 4 - Richtersveld Component # 5 - The West Coast Module # 5 - Karoo Region Component # 1 - Introduction to the Karoo and N12 towns Component # 2 - Towns along the N1, N9 and N10 Component # 3 - Other Karoo towns Module # 6 - Diamond Region Component # 1 - Kimberley Component # 2 - Battlefields and towns along the N12 Module # 7 - The Green Kalahari Component # 1 – The Green Kalahari Module # 8 - The Kalahari Component # 1 - Kuruman and towns along the N14 South and R31 Northern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus. It may not be copied, distributed or reproduced in any format whatsoever without the express written permission of WildlifeCampus. 3 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module 1 - Component 1 Northern Cape Province Overview Introduction Diamonds certainly put the Northern Cape on the map, but it has far more to offer than these shiny stones. -

Provincial Gazette Kasete Ya Profensi Igazethi Yephondo

NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE PROFENSI VA KAPA-BOKONE NOORD-KAAP PROVINSIE IPHONDO lOMNTlA KOlONI Provincial Gazette iGazethi YePhondo Kasete ya Profensi Provinsiale Koerant KIMBERLEY Vol. 26 18 NOVEMBER 2019 No. 2308 18 NOVEMBER 2019 2 No. 2308 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, 18 NOVEMBER 2019 PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 18 NOVEMBER 2019 No.2308 3 CONTENTS Gazette Page No. No. GENERAL NOTICES' ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 121 Northern Cape Garnbling Act (3/2008): Applications received for Type B' Site Operator licences frorn Route Operator Vukani Garning Northern Cape (Pty) Ltd ............................................................................................ 2308 14 122 Northern Cape Garnbling Act (3/2008): Applications received for Site Operator licence frorn Route Operator Crazy Slots Northern Cape: Ultra-Diarnond Rush ............................................................................................. 2308 16 123 Northern Cape Garnbling Act (3/2008): Applications received for Type B' Site Operator licences frorn Route Operator Vukani Garning Northern Cape (Pty) Ltd ............................................................................................ 2308 18 124 Northern Cape Garnbling Act (3/2008): Applications received for Site Operator licence frorn Route Operator Crazy Slots Northern Cape: Ultra-Diarnond Rush ............................................................................................. 2308 20 125 Northern Cape Garnbling Act (3/2008): Applications received for Type B' Site Operator licence frorn Route Operator Crazy Slots -

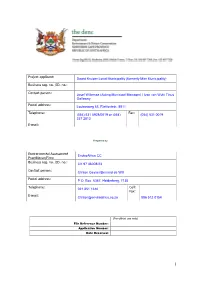

Project Applicant: Dawid Kruiper Local Municipality (Formerly Mier Municipality) Business Reg

Project applicant: Dawid Kruiper Local Municipality (formerly Mier Municipality) Business reg. no. /ID. no.: Contact person: Josef Willemse (Acting Municipal Manager) / Ivan van Wyk/ Tinus Galloway Postal address: Loubosweg 63, Rietfontein, 8811 Telephone: Fax: (054) 531 0928/0019 or (054) (054) 531 0019 337 2813 E-mail: Prepared by: Environmental Assessment EnviroAfrica CC Practitioner/Firm: Business reg. no. /ID. no.: CK 97 46008/23 Contact person: Clinton Geyser/Bernard de Witt Postal address: P.O. Box. 5367, Helderberg, 7135 Telephone: Cell: 021 851 1616 Fax: E-mail: [email protected] 086 512 0154 (For official use only) File Reference Number: Application Number: Date Received: 1 Basic Assessment Report in terms of the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations, 2014, promulgated in terms of the National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998), as amended. Kindly note that: • This basic assessment report is a standard report that may be required by a competent authority in terms of the EIA Regulations, 2014 and is meant to streamline applications. Please make sure that it is the report used by the particular competent authority for the activity that is being applied for. • This report format is current as of 08 December 2014. It is the responsibility of the applicant to ascertain whether subsequent versions of the form have been published or produced by the competent authority • The report must be typed within the spaces provided in the form. The size of the spaces provided is not necessarily indicative of the amount of information to be provided. The report is in the form of a table that can extend itself as each space is filled with typing. -

Emalahleni Municipality Final

TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................................... ...................................................................................................................................................... PERSPECTIVE FROM THE EXECUTIVE MAYOR .................................................................. I PERSPECTIVE OF THE SPEAKER ......................................................................................... II PERSPECTIVE FROM THE MUNICIPAL MANAGER ........................................................... III LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................................. IV 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 LOCATION ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 GUIDING PARAMETERS ........................................................................................................ 5 1.1.1 LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 5 2 PROCESS PLAN ..................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1 COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION MEETINGS .......................................................................................... -

Census of Agriculture Provincial Statistics 2002- Northern Cape Financial and Production Statistics

Census of Agriculture Provincial Statistics 2002- Northern Cape Financial and production statistics Report No. 11-02-04 (2002) Department of Agriculture Statistics South Africa i Published by Statistics South Africa, Private Bag X44, Pretoria 0001 © Statistics South Africa, 2006 Users may apply or process this data, provided Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) is acknowledged as the original source of the data; that it is specified that the application and/or analysis is the result of the user's independent processing of the data; and that neither the basic data nor any reprocessed version or application thereof may be sold or offered for sale in any form whatsoever without prior permission from Stats SA. Stats SA Library Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) Data Census of agriculture Provincial Statistics 2002: Northern Cape / Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, Statistics South Africa, 2005 XXX p. (Report No. 11-02-01 (2002)). ISBN 0-621-36446-0 1. Agriculture I. Statistics South Africa (LCSH 16) A complete set of Stats SA publications is available at Stats SA Library and the following libraries: National Library of South Africa, Pretoria Division Eastern Cape Library Services, King William’s Town National Library of South Africa, Cape Town Division Central Regional Library, Polokwane Library of Parliament, Cape Town Central Reference Library, Nelspruit Bloemfontein Public Library Central Reference Collection, Kimberley Natal Society Library, Pietermaritzburg Central Reference Library, Mmabatho Johannesburg Public Library This report is available -

Emalahleni Local Municipality Integrated Development Plan | 2019/2020 Final Idp

TABLE OF CONTENTS PERSPECTIVE FROM THE EXECUTIVE MAYOR .................................................................. I PERSPECTIVE OF THE SPEAKER ........................................................................................ III PERSPECTIVE FROM THE MUNICIPAL MANAGER ........................................................... IV LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................... V 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 LOCATION ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 GUIDING PARAMETERS ........................................................................................................ 5 1.1.1 LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 5 2 PROCESS PLAN ..................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1 COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION MEETINGS ........................................................................................... 23 3 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................ 26 3.1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... -

1629 7-9 Ncapeliq Layout 1

NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE PROFENSI YA KAPA-BOKONE NOORD-KAAP PROVINSIE IPHONDO LOMNTLA KOLONI EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWONE Provincial Gazette iGazethi YePhondo Kasete ya Profensi Provinsiale Koerant Vol. 19 KIMBERLEY, 7 SEPTEMBER 2012 No. 1629 We oil hawm he power to preftvent kllDc AIDS HEIRINE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes J12-241586—A 1629—1 PROVINCE OF THE NORTHERN CAPE 2 No. 1629 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY, 7 SEPTEMBER 2012 ANNUAL PRICE INCREASE FOR PUBLICATION OF A LIQUOR LICENCE: FOR THE FOLLOWING PROVINCES: (AS FROM 1 APRIL 2012) NORTHERN CAPE LIQUOR LICENCES: R187.15. GAUTENG LIQUOR LICENCES: R187.15. ALL OTHER PROVINCES: R114.05. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICES ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 67 Northern Cape Liquor Act, 2008: Notice 67 Noord-Kaap Drankwet, 2008: Kennis - of intention to apply in terms of section gewing van voorneme om kragtens 20 of the Act for a licence....................... 4 1629 artikel 20 van die Wet vir ’n lisensie 68 do.: Notice of intention to apply in terms aansoek te doen .................................... 5 1629 of section 20 (1) (d) of the Act for the per- 68 do.: Kennisgewing van voorneme om manent/temporary transfer of a licence kragtens artikel 20 (1) (d) van die wet vir to other premises .................................... 8 1629 die permanente/tydelike oordrag van lisensie na ’n ander perseel aansoek te doen ........................................................ 9 1629 IMPORTANT NOTICE WHEN SUBMITTING LIQUOR NOTICES FOR PUBLICATION, CONTACT PARTICULARS ARE AS FOLLOWS: PHYSICAL ADDRESS: POSTAL ADDRESS: Government Printing Works Private Bag X85 149 Bosman Street Pretoria Pretoria 0001 CONTACT PERSON: Hester Wolmarans Tel. -

Vegetation, Habitats and Browse Availability in the Waterval Section, Augrabies Falls National Park

Paper 1: Vegetation, habitats and browse availability in the Waterval section, Augrabies Falls National Park – place of scarcity and diversity. Kenneth G. Buk Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, 1 Universitetsparken, 2100, Denmark. [email protected] Abstract Factors potentially affecting habitat suitability for large browsers were quantified in 7530 ha of mountainous desert in Waterval, Augrabies Falls National Park, western South Africa. The vegetation was classified and mapped according to plant species associations. In each vegetation community vertical cover, shade, substrate composition as well as canopy volume of each browse species were measured. Furthermore, water availability and steepness of slopes were mapped. The varied topography and soils of Waterval result in a high diversity of browse (D=19.0, H’(ln)=3.45) divided into ten vegetation communities including seven shrublands (61.7 % by area), two woodlands (37.1 %) and a riverine forest (1.1 %). The average browse availability 0-200 cm above ground is 1 096 ±90 m 3/ha, ranging from 597 to 14 446 m 3/ha among vegetation communities. The browse includes Acacia mellifera (15.0 %), Schotia afra (12.7 %), Monechma spartioides (4.5 %), Acacia karroo (4.2 %), Boscia albitrunca (3.8 %), Euphorbia rectirama (2.9 %) and Indigofera pechuelii (2.6 %). The riverine forest provides easy access to water, browse, shade and vertical cover. However, some 97 % of Waterval has scarce browse and vertical cover as well as little to no shade. In addition, the northeastern area is steep, 4-6 km from water and bordered by a low-use road. Fortunately, with the exception of community 3, browse is diverse, generally palatable and deciduousness limited to 2-3 months in one major browse species. -

36740 16-8 Road Carrier Permits

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA August Vol. 578 Pretoria, 16 2013 Augustus No. 36740 PART 1 OF 2 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 303563—A 36740—1 2 No. 36740 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 AUGUST 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the senderʼs respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 36740 Menlyn..................................................... 3 36740 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke -

Environmental Impact Assessments

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENTS: ABATTOIR APPLICATIONS Abattoir project – Welkom Department of Agriculture Free State Province Abattoir project – Welkom Private Applicant AGRICULTURE RELATED APPLICATIONS Feed and fertilizer manufacturing facilities – Private Applicant Wesselsbron Breeding and conservation farm – Vredefort Johannesburg Zoo South African Technology Demonstration Centre – Joint venture between South Gariep (Fishery) Africa and China Feedlot developments: Bultfontein Theunissen Private Applicants Vredefort Free State Province Zastron Development of chicken farming infrastructure: Bethulie Bloemfontein Brandfort Koffiefontein Private Applicants Smithfield Soutpan Springfontein Wesselsbron Development of chicken farming infrastructure: Balfour Private Applicants Gauteng Province Bronkhorstspruit Chemvet Krugersdorp Nigel Development of chicken farming infrastructure – Northern Cape Province Private Applicant Postmasburg Development of chicken farming infrastructure: Makwassie North West Province Private Applicants Ventersdorp Zeerust BILLBOARD INFRASTRUCTURE KwaZulu-Natal Province Erection of billboard infrastructure – Durban Outdoor Network ELECTRICITY INFRASTRUCTURE & GENERATION PROJECTS Construction of a 132kV power line – Bloemfontein Centlec Construction & refurbishment of a 66kV power line Eskom – Springfontein to Reddersburg Free State Province Construction of a 22/11kV power line reticulation from the Hydro Power Station on the Ash River to Bethlehem Hydro Bethlehem Development of a Hydro-Electric -

Nc Travelguide 2016 1 7.68 MB

Experience Northern CapeSouth Africa NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Tel: +27 (0) 53 832 2657 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 Email:[email protected] www.experiencenortherncape.com 2016 Edition www.experiencenortherncape.com 1 Experience the Northern Cape Majestically covering more Mining for holiday than 360 000 square kilometres accommodation from the world-renowned Kalahari Desert in the ideas? North to the arid plains of the Karoo in the South, the Northern Cape Province of South Africa offers Explore Kimberley’s visitors an unforgettable holiday experience. self-catering accommodation Characterised by its open spaces, friendly people, options at two of our rich history and unique cultural diversity, finest conservation reserves, Rooipoort and this land of the extreme promises an unparalleled Dronfield. tourism destination of extreme nature, real culture and extreme adventure. Call 053 839 4455 to book. The province is easily accessible and served by the Kimberley and Upington airports with daily flights from Johannesburg and Cape Town. ROOIPOORT DRONFIELD Charter options from Windhoek, Activities Activities Victoria Falls and an internal • Game viewing • Game viewing aerial network make the exploration • Bird watching • Bird watching • Bushmen petroglyphs • Vulture hide of all five regions possible. • National Heritage Site • Swimming pool • Self-drive is allowed Accommodation The province is divided into five Rooipoort has a variety of self- Accommodation regions and boasts a total catering accommodation to offer. • 6 fully-equipped • “The Shooting Box” self-catering chalets of six national parks, including sleeps 12 people sharing • Consists of 3 family units two Transfrontier parks crossing • Box Cottage and 3 open plan units sleeps 4 people sharing into world-famous safari • Luxury Tented Camp destinations such as Namibia accommodation andThis Botswanais the world of asOrange well River as Cellars. -

NC Sub Oct2016 ZFM-Postmasburg.Pdf

# # !C # ### # ^ #!.C# # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # ## # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C # # # # # ## # #!C# # # # # # #!C # # ^ ## # !C# # # # # # ## # # # # #!C # # ^ !C # # # ^# # # # # # # ## ## # ## # # !C # # # !C# ## # !C# # ## # # # # #!C # # # #!C##^ # # # # # # # # # # # #!C# ## ## # ## # # # # # # ## # ## # # # ## #!C ## # ## # # !C### # # # # # # # # # # # # !C## # # ## #!C # # # ##!C# # # # ##^# # # # # ## ###!C# # ## # # # ## # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # ## # # ## !C# #^ # #!C # # !C# # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## ## # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # ### # # ## ## # # # # ### ## ## # # # # !C# # !C # # # #!C # # # #!C# ### # #!C## # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # ## ## # # ## # # ## # # # # # # ## ### ## # ##!C # ## # # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ ## # #### ## # # # # # # #!C# # ## # ## #!C## # #!C# ## # # !C# # # ##!C#### # # ## # # # # # !C# # # # ## ## # # # # # ## # ## # # # ## ## ##!C### # # # # # !C # !C## #!C # !C # #!.##!C# # # # ## # ## ## # # ### #!C# # # # # # # ## ###### # # ## # # # # # # ## ## #^# ## # # # ^ !C## # # !C# ## # # ### # # ## # ## # # ##!C### ##!C# # !C# ## # ^ # # # !C #### # # !C## ^!C#!C## # # # !C # #!C## #### ## ## #!C # ## # # ## # # # ## ## ## !C# # # # ## ## #!C # # # # !C # #!C^# ### ## ### ## # # # # # !C# !.### # #!C# #### ## # # # # ## # ## #!C# # # #### # #!C### # # # # ## # # ### # # # # # ## # # ^ # # !C ## # # # # !C# # # ## #^ # # ^ # ## #!C# # # ^ # !C# # #!C ## # ## # # # # # # # ### #!C# # #!C # # # #!C # # # # #!C #!C### # # # # !C# # # # ## # # # # # # # #