Elections for Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Democratic Peace Theory: Validity in Relation to the European Union and 'Peaceful' Cooperation Between United States and China

Vol.7(2), pp. 15-17, May 2016 DOI: 10.5897/IJPDS2015.0234 Article Number: 1BC2EFE58946 International Journal of Peace and ISSN 2141–6621 Copyright © 2016 Development Studies Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJPDS Short Communication The democratic peace theory: Validity in relation to the European Union and 'Peaceful' cooperation between United States and China Nibal Attia Department of political Science, Misr University for Science and Technology, Egypt. Recieved 20 April, 2015; Accepted 31 March, 2016 According to the democratic peace theory, democratic states are less likely to go to war with other democratic states. Consequently, the ultimate goal of the theory is to create a world of democracies that is, a world without war. However, from the realist perspective in some cases democracies go to war with other democracies to influence their power. This paper will critically analyze the validity of democratic peace theory in its assumption that democracies rarely fight each other, by providing the example of the establishment of the European Union, in which democracies are co-operating with each other to achieve their common good. The paper is divided into three parts; the first one will provide an explanation of the Peace Democratic theory and its main assumptions. The second one will evaluate to what extent these assumptions are practical ones through the application of the case studies. Then a counter-argument for one of its assumption will be included questioning the core claim of the democratic peace theory from the commercial peace theory perspective. Key words: Democracy, peace theory, war, co-operation. -

What Kant Preaches to the UN: Democratic Peace Theory and “Preventing the Scourge of War”

EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES − INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL ON EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES VOLUME 9, NUMBER 1 (16), PP 65-84, OCTOBER 2018 What Kant preaches to the UN: democratic peace theory and “preventing the scourge of war” Bekim Sejdiu1 ABSTRACT This paper exploits academic parameters of the democratic peace theory to analyze the UN’s principal mission of preserving the world peace. It inquires into the intellectual horizons of the democratic peace theory – which originated from the Kant’s “perpetual peace” – with the aim of prescribing an ideological recipe for establishing solid foundation for peace among states. The paper argues that by promoting democracy and supporting democratization, the UN primarily works to achieve its fundamental mission of preventing the scourge of war. It explores practical activities that the UN undertakes to support democracy, as well as the political and normative aspects of such an enterprise, is beyond the reach of this analysis. Rather, the focus of the analy- sis is on the democratic peace theory. The confirmation of the scientific credibility of this theory is taken as a sufficient argument to claim that by supporting democracy the UN would advance one of its major purposes, namely the goal of peace. KEY WORDS: democracy, peace, Kant, UN POVZETEK Prispevek na osnovi teorije demokratičnega miru analizira temeljno misijo OZN, to je ohranitev svetovnega miru. Poglablja se v intelektualna obzorja teorije demokratičnega miru – ki izhaja iz Kantovega “večnega miru” – s ciljem začrtati ideološki recept za vzpostavitev čvrstih teme- ljev za mir med državami. Prispevek zagovarja hipotezo, da OZN s promoviranjem demokracije in z njenim podpiranjem predvsem prispeva k izpolnitvi svojega temeljnega poslanstva, to je preprečevati izbruh vojn. -

A Challenge to Democratic Peace Theory: U.S. Intervention in Chile, 1973

A Challenge to Democratic Peace Theory: U.S. Intervention in Chile, 1973 by Carissa Faye Margraf Washington and Lee University Class of 2021 [email protected] In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts in Politics with Honors Thesis Advisor: Dr. Zoila Ponce de Leon Second Reader: Dr. Brian Alexander Lexington, Virginia Spring 2021 Margraf 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank those who have supported me throughout my academic journey. Without you, I would not be where I am today. To my family, I will forever be grateful for the hours that you allowed me to ramble about Chile and covert action as I refined my argument, and for the attentive nods and encouragement throughout this process. To my friends, thank you for the much-needed thesis breaks of badminton, movies, and check-ins after long nights. I would also like to thank my wonderful Thesis Advisor, Dr. Zoila Ponce de Leon, for her endless support and dedication, and my Second Reader, Dr. Brian Alexander, for his thorough feedback and enthusiasm. Finally, I would like to thank my mom, who we lost at the start of my sophomore year. While she is not here to experience these final moments of my time at Washington and Lee University, I am confident that she would be glowing with pride. Margraf 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS I: EVERY THEORETICAL CHALLENGE REQUIRES A CATALYST o Abstract o Introduction o Thesis II: METHODOLOGY III: THEORETICAL BACKGROUND o Democratic Peace Theory ▪ Origin ▪ Contents of the Theory ▪ Normative vs Structural Logic ▪ Debates of -

Governance, Democracy Peace

AND GOVERNANCE, DEMOCRACY PEACE HOW STATE CAPACITY AND REGIME TYPE INFLUENCE THE PROSPECTS FOR WAR AND PEACE David Cortright with Conor Seyle and Kristen Wall © 2013 One Earth Future Foundation The One Earth Future Foundation was founded in 2007 with the goal of supporting research and practice in the area of peace and governance. OEF believes that a world beyond war can be achieved by the development of new and effective systems of cooperation, coordination, and decision making. We believe that business and civil society have important roles to play in filling governance gaps in partnership with states. When states, business, and civil society coordinate their efforts, they can achieve effective, equitable solutions to global problems. As an operating foundation, we engage in research and practice that supports our overall mission. Research materials from OEF envision improved governance structures and policy options, analyze and document the performance of existing governance institutions, and provide intellectual support to the field operations of our implementation projects. Our active field projects apply our research outputs to existing governance challenges, particularly those causing threats to peace and security. ONE EARTH FUTURE FOUNDATION 525 Zang Street | Suite C Broomfield, CO 80021 USA Ph. +1.303.533.1715 | Fax +1 303.309.0386 ABOUT THE AUTHORS David Cortright is the director of Policy Studies at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame and chair of the board of directors of the Fourth Freedom Forum. He is the author of seventeen books, including the Adelphi volume Towards Nuclear Zero, with Raimo Vayrynen (Routledge, 2010) and Peace: A History of Movements and Ideas (Cambridge University Press, 2008). -

Democratization and Democratic Peace. Sarah K

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2019 Democratization and Democratic peace. Sarah K. Simon University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Simon, Sarah K., "Democratization and Democratic peace." (2019). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 198. Retrieved from https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors/198 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Simon 1 Democratization and Democratic Peace By Sarah Katherine Simon Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude and for Graduation with Honors from the Department of Political Science University of Louisville May 2019 Simon 2 I. Introduction The theory of democratic peace states that democratic countries will not go to war with other democratic countries (Rasler 2005). A country must first consolidate to a democracy before it can experience the benefits of democratic peace; therefore, how will the previous regime affect the transition process? Taking previous regime into consideration would assist transitioning governments by determining if certain types of regimes are more likely to have a successful democratic transition (Schneider 2004). -

Can Democracy Create World Peace?

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository The University Dialogue Discovery Program 2007 Can democracy create world peace? Alynna J. Lyon University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/discovery_ud Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Lyon, Alynna J., "Can democracy create world peace?" (2007). The University Dialogue. 24. https://scholars.unh.edu/discovery_ud/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Discovery Program at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University Dialogue by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Can Democracy Create World Peace? Democratic Peace Theory: Misguided Policy or Panacea Alynna Lyon Department of Political Science an democracy create world peace? The idea that Democratic Peace and Political Science representative liberal governments can dimin- In the 1970s, scholars began using the tools of social ish the occurrence of war is one of the most science to explore this thesis and have uncovered a Cappealing, influential, and at the same time, contro- significant amount of empirical research that supports versial ideas of our time. For centuries, thinkers have these claims. Today there are over a hundred authors proposed that a world of democratic countries would who have published scholarly works on the Democratic be a peaceful world. As early as 1795, Immanuel Kant Peace Theory. One study examined 416 country-to- wrote in his essay Perpetual Peace that democracies country wars from 1816-1980 and found that only 12 are less warlike. -

Challenging the Democratic Peace Theory - the Role of US-China Relationship Toni Ann Pazienza University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 3-25-2014 Challenging the Democratic Peace Theory - The Role of US-China Relationship Toni Ann Pazienza University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Pazienza, Toni Ann, "Challenging the Democratic Peace Theory - The Role of US-China Relationship" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5098 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Challenging the Democratic Peace Theory: The Role of the U.S.-China Relationship by Toni A. Pazienza A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Government and International Affairs College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Steven C. Roach, Ph.D. Harry E. Vanden, Ph.D. Earl Conteh-Morgan, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 25, 2014 Keywords: Kant, Democratic Peace Theory, Democracy, Communism, United States, China, Liberalism, Realism, and Trade Interdependence Copyright © 2014, Toni A. Pazienza Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... -

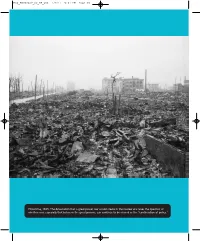

Hiroshima, 1945. the Devastation That a Great Power War Would Create In

M04_BOVA2407_00_SE_C04 1/7/11 5:01 PM Page 98 Hiroshima, 1945. The devastation that a great power war would create in the nuclear era raises the question of whether war, especially that between the great powers, can continue to be viewed as the “continuation of policy.” M04_BOVA2407_00_SE_C04 1/7/11 5:01 PM Page 99 CHAPTER 4 War and Violence in World Politics The Realist’s World Unlike breathing, eating, or sex, war is not something that is somehow required by the human condition or the forces of history. Conflicts of interest are inevitable and continue to exist within the developed world. But the notion that war should be used to resolve them has increasingly been discredited and abandoned.1 —John Mueller, 1989 The optimists’ claim that security competition and war among the great powers have been burned out of the system is wrong. In fact, all of the major states around the globe still care deeply about the balance of power and are destined to compete for power among themselves for the foreseeable future. In short, the real world remains a realist world.2 —John Mearsheimer, 2001 hroughout human history, war and the threat of war have been a constant part of international life and central to understanding how the world works. Though Tall of the international relations paradigms provide explanations for the existence and frequency of war, the structural realist view that war is rooted in international anarchy provides least cause to expect that war can ever be substantially eliminated. In a world with no effective and reliable higher authority to impose order, realists insist that states will from time to time need to protect their vital interests through the use of force and violence. -

The Democratic Peace Theory and Its Problems

The Democratic Peace Theory and Its Problems Munafrizal Manan Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Universitas Al Azhar Indonesia, Jakarta E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This essay discusses the democratic peace theory from the perspective of both its proponents and opponents. The puzzle of the democratic peace theory has long been debated methodologically and empirically. Both have a strong argument to support their views, however. This essay highlights the debate by focusing on the three problems of the democratic peace theory. First, the differences of the definitions of democracy, war, and peace that demonstrates the lack of robustness in the democratic peace theory. Second, democracy by force has often failed to establish peace whether international or domestic peace and therefore the promotion of democracy around the world have been seen as a justification of democratic intervention to other sovereign states. Third, the democratic peace theory does not always apply in new emerging democratic countries. As a result, it raises a question whether the democratic peace theory is an academic theory or an ideology. Keywords: Democracy, Peace, War, Democratic Peace, Kant. Abstrak: Esai ini mendiskusikan teori perdamaian demokratik dari perspektif pendukung dan penentang teori ini. Teka-teki teori ini telah lama diperdebatkan secara metodologis dan empiris. Pendukung dan penentang teori ini sama-sama memiliki argumen kuat untuk mendukung pandangan mereka. Esai ini menyoroti perdebatan tersebut melalui fokus pada tiga masalah yang melekat pada teori perdamaian demokratik. Pertama, menyoroti perbedaan definisi demokrasi, perang, dan perdamaian yang menunjukkan kurang kuatnya teori ini. Kedua, menyoroti aspek demokrasi melalui paksaan yang ternyata sering gagal menegakkan perdamaian dalam lingkup domestik maupun internasional, dan karena itu promosi demokrasi ke seluruh dunia dipandang sebagai sekadar justifikasi untuk mengintervensi negara-negara berdaulat. -

Neo-Conservatism and Foreign Policy

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2009 Neo-conservatism and foreign policy Ted Boettner University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Boettner, Ted, "Neo-conservatism and foreign policy" (2009). Master's Theses and Capstones. 116. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neo-Conservatism and Foreign Policy BY TED BOETTNER BS, West Virginia University, 2002 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science September, 2009 UMI Number: 1472051 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI" UMI Microform 1472051 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

The Power of Perception: Securitization, Democratic Peace, and Enduring Rivalries

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 The Power of Perception: Securitization, Democratic Peace, and Enduring Rivalries Derrick Charles Seaver Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Seaver, Derrick Charles, "The Power of Perception: Securitization, Democratic Peace, and Enduring Rivalries" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 700. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/700 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF PERCEPTION: SECURITIZATION, DEMOCRATIC PEACE, AND ENDURING RIVALRIES A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By Derrick Charles Seaver B.A., Wright State University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL February 19, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Derrick Seaver ENTITLED The Power of Perception: Securitization, Democratic Peace, and Enduring Rivalries BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. ______________________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. Thesis Director ______________________________ Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: ___________________________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Liam Anderson, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. ______________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate School ABSTRACT Seaver, Derrick. -

The Democratic Peace Theory and Biopolitics

The Democratic Peace Theory and Biopolitics Michael Lewis Nagy Thesis submitted to the faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Masters of Arts In Political Science Scott Nelson, Chair Priya Dixit Yannis Stivachtis May 2, 2017 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: biopolitics, democratic peace theory, terrorism The Democratic Peace Theory and Biopolitics Michael Lewis Nagy Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to inquire into the hard decisions that democracies are making in the 21st century in the context of working to spreading democracy and maintaining peace through foreign policy. Ever since the American-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq after the 9/11 terror attacks, democratic peace theorists have been pushed further to the sidelines as their theory has been put to the test and struggled to stand up to the challenges of political realities in contemporary world politics. The idea that the diffusion of democracy would help build a Kantian world peace would seem to have taken a severe blow with the rise of populist candidates and policies in the West in recent years. The democratic peace theory (DPT) is in crucial respects about the mechanisms to indirectly control other countries’ economies and politics through forcibly installing democratic regimes. Though done in the name of safety and security for western nations, this foreign policy looks an awful lot like an attempt at biopolitical engineering. Has DPT morphed into a form of biopolitics? The goal of this thesis is to delve into this question and to learn what the implications are if this is the case, and what it means for the West, democracies, terrorism, and societies.