Bothrops Lanceolatus Snakebite Surgical Management—Relevance of Fasciotomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetic Diversity, Habitat Loss and Conservation in South

Diversity and Distributions, (Diversity Distrib.) (2014) 20, 1108–1119 BIODIVERSITY Phylogenetic diversity, habitat loss and RESEARCH conservation in South American pitvipers (Crotalinae: Bothrops and Bothrocophias) Jessica Fenker1, Leonardo G. Tedeschi1, Robert Alexander Pyron2 and Cristiano de C. Nogueira1*,† 1Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade de ABSTRACT Brasılia, 70910-9004 Brasılia, Distrito Aim To analyze impacts of habitat loss on evolutionary diversity and to test Federal, Brazil, 2Department of Biological widely used biodiversity metrics as surrogates for phylogenetic diversity, we Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G. St. NW, Washington, DC 20052, study spatial and taxonomic patterns of phylogenetic diversity in a wide-rang- USA ing endemic Neotropical snake lineage. Location South America and the Antilles. Methods We updated distribution maps for 41 taxa, using species distribution A Journal of Conservation Biogeography models and a revised presence-records database. We estimated evolutionary dis- tinctiveness (ED) for each taxon using recent molecular and morphological phylogenies and weighted these values with two measures of extinction risk: percentages of habitat loss and IUCN threat status. We mapped phylogenetic diversity and richness levels and compared phylogenetic distances in pitviper subsets selected via endemism, richness, threat, habitat loss, biome type and the presence in biodiversity hotspots to values obtained in randomized assemblages. Results Evolutionary distinctiveness differed according to the phylogeny used, and conservation assessment ranks varied according to the chosen proxy of extinction risk. Two of the three main areas of high phylogenetic diversity were coincident with areas of high species richness. A third area was identified only by one phylogeny and was not a richness hotspot. Faunal assemblages identified by level of endemism, habitat loss, biome type or the presence in biodiversity hotspots captured phylogenetic diversity levels no better than random assem- blages. -

Third-Generation Antivenomics Analysis of the Preclinical Efficacy Of

Toxicon: X 1 (2019) 100004 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Toxicon: X journal homepage: www.journals.elsevier.com/toxicon-x Third-generation antivenomics analysis of the preclinical efficacy of ® T Bothrofav antivenom towards Bothrops lanceolatus venom ∗ Davinia Plaa, Yania Rodrígueza, Dabor Resiereb, Hossein Mehdaouib, José María Gutiérrezc, , ∗∗ Juan J. Calvetea, a Laboratorio de Venómica Evolutiva y Traslacional, Instituto de Biomedicina de Valencia, CSIC, Jaime Roig 11, 46010 Valencia, Spain b Service des Urgences et de Reanimation Polyvalente, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Fort-de-France, Martinique, France c Instituto Clodomiro Picado, Facultad de Microbiología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT ® Keywords: Bothrops lanceolatus inflicts severe envenomings in the Lesser Caribbean island of Martinique. Bothrofav , a Bothrops lanceolatus monospecific antivenom against B. lanceolatus venom, has proven highly effective at the preclinical and clinical ® Antivenom levels. Here, we report a detailed third-generation antivenomics quantitative analysis of Bothrofav . With the Snake venom ® ® exception of poorly-immunogenic peptides, Bothrofav immunocaptured all the major protein components. Bothrofav These results, along with previous preclinical and clinical observations, underscore the high neutralizing efficacy Third-generation antivenomics of the antivenom against B. lanceolatus venom. Martinique Bothrops lanceolatus is an endemic viperid snake in the French and therapeutic antibody molecules present in an antivenom. Thus, overseas Department of Martinique, in the Lesser Caribbean, where it neutralization assays and antivenomics complement each other in the represents the only venomous snake (Campbell and Lamar, 2004). En- characterization of the preclinical efficacy of antivenoms (Gutiérrez venomings by this species are similar to those inflicted by other Bo- et al., 2017). -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

Coagulotoxicity of Bothrops (Lancehead Pit-Vipers) Venoms from Brazil: Differential Biochemistry and Antivenom Efficacy Resulting from Prey-Driven Venom Variation

toxins Article Coagulotoxicity of Bothrops (Lancehead Pit-Vipers) Venoms from Brazil: Differential Biochemistry and Antivenom Efficacy Resulting from Prey-Driven Venom Variation Leijiane F. Sousa 1,2, Christina N. Zdenek 2 , James S. Dobson 2, Bianca op den Brouw 2 , Francisco Coimbra 2, Amber Gillett 3, Tiago H. M. Del-Rei 1, Hipócrates de M. Chalkidis 4, Sávio Sant’Anna 5, Marisa M. Teixeira-da-Rocha 5, Kathleen Grego 5, Silvia R. Travaglia Cardoso 6 , Ana M. Moura da Silva 1 and Bryan G. Fry 2,* 1 Laboratório de Imunopatologia, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo 05503-900, Brazil; [email protected] (L.F.S.); [email protected] (T.H.M.D.-R.); [email protected] (A.M.M.d.S.) 2 Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (C.N.Z.); [email protected] (J.S.D.); [email protected] (B.o.d.B.); [email protected] (F.C.) 3 Fauna Vet Wildlife Consultancy, Glass House Mountains, QLD 4518, Australia; [email protected] 4 Laboratório de Pesquisas Zoológicas, Unama Centro Universitário da Amazônia, Pará 68035-110, Brazil; [email protected] 5 Laboratório de Herpetologia, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo 05503-900, Brazil; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (M.M.T.-d.-R.); [email protected] (K.G.) 6 Museu Biológico, Insituto Butantan, São Paulo 05503-900, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 September 2018; Accepted: 8 October 2018; Published: 11 October 2018 Abstract: Lancehead pit-vipers (Bothrops genus) are an extremely diverse and medically important group responsible for the greatest number of snakebite envenomations and deaths in South America. -

SHIS 089.Pdf

L HO CHECKLIST AND BIBLIOGRAPHY (1960-85) OF THE VENEZUELAN HERPETOFAUNA JAIME E. PEFAUR Ecologia Animal Facultad de Ciencias Universidad de Los Andes SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 89 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are. distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research- laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and*Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The Venezuelan herpetofauna is fairly large compared to any other belonging to a tropical country of similar area. The diversity is due to both a complex physiography and an active speciation process. The present checklist includes, to the best of my knowledge, all species recorded for Venezuela and described through December 1990. Of the 490 recorded taxa, 15% have been described in the last two decades. The process of description could be stronger if a checklist were available; however, there is no such list. Because many additional species are known but not described and many additional ones awaiting discovery, I offer this checklist as a base line reference tool, realizing that it will require continuing modifications to keep it current with new research discoveries and systematic rearrangements. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: VIPERIDAE Bothro S

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: VIPERIDAE Catalogue of American Amphbians and Reptiles. Powell, R, and R.D. Wittenberg. 1998. Bothrops caribbaeus. Bothro s caribbaeus (Garman) gint Lucia Laneeherd Bothrops subscutatus Gray 1842:47. Type locality, "Demerara." Holotype not designated, but is (G. Underwood, in litt., 8.V111.92, to J.D. Lazell, Jr.: P.J. Stafford, in litt., 26.V11.98), British Museum (Natural History) (BMNH) 1946.1.19.59, an adult female, collected by E. Sabine, date of collection un- known, but likely early 1930s (not examined by authors). Itlcertae sedis (see Nomenclatural History). Bothrops Sabinii Gray 1842:47. Type locality, "Demerara." . - . Syntypes not designated, but are (G. Underwood, in litt., 25 krn 8.VIII.92, to J.D. Lazell, Jr.; P.J. Stafford, in litt.. 26.VII.98). BMNH 1946.1.18.65, a subadult female, 1946.1.19.65. an adult female, 1946.1.19.66, a subadult male, all collected by E. Sabine, dates of collection utiknown (not examined by au- Map. Range of Borhrops caribbaeus (modified from Lazell 1964 and thors). Incertae sedis (see Nomenclatural History). Schwm. and Henderson 1991): the restricted type locality is niarked Bothrops cinereus Gray 1842:47. Type locality, "America," al- with a circle. dots indicate s. though Gray ( 1849) indicated "South America." Holotype not designated, but is (P.J. Stafford, in litt., 26.V11.98), BMNH 1946.1.18.77, a subadult female, collected by E. MacLeay, date of collection unknown, but likely before 1937; the origi- nal label is missing from this bottle (not examined by au- thors). Incertae seclis (see Nomenclatural History). -

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

WWW.IRCF.ORG TABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES &IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 27(2):147–153 • AUG 2020 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES . Chasing NotesBullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer on sayi) in Wisconsin:the Feeding Habits On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Sharedof History the of Treeboas (CaribbeanCorallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: Watersnake, A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 RESEARCHTretanorhinus ARTICLES variabilis (Dipsadidae) . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 Yaira López-Hurtado. The Knight1, L. Anole Yusnaviel (Anolis equestris García-Padrón) in Florida 2, Adonis González1, Luis M. Díaz3, and Tomás M. Rodríguez-Cabrera4 .............................................Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 1Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, La Habana 11900, Cuba ([email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]) CONSERVATION2Museo de Historia Natural ALERT “Tranquilino Sandalio de Noda,” Martí 202, Pinar del Río, Cuba ([email protected]) . World’s Mammals3Museo in Nacional Crisis .............................................................................................................................. -

Bonn Zoological Bulletin - Früher Bonner Zoologische Beiträge

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Bonn zoological Bulletin - früher Bonner Zoologische Beiträge. Jahr/Year: 2012 Band/Volume: 61 Autor(en)/Author(s): Wagner Philipp, Bauer Aaron M., Böhme Wolfgang Artikel/Article: Amphibians and reptiles collected by Moritz Wagner, with a focus on the ZFMK collection 216-240 © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zoologicalbulletin.de; www.biologiezentrum.at Bonn zoological Bulletin 61 (2): 216-240 December 2012 Amphibians and reptiles collected by Moritz Wagner, with a focus on the ZFMK collection ^ Philipp Wagner , Aaron M. Bauer' & Wolfgang Bohme^ Department ofBiology, Villanova University, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, Pennsylvania 19085, USA. Zoologisches Forschungsmiiseum A. Koenig, Adenaiierallee 160, D-53113 Bonn, Germany. 'Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract. Moritz Wagner (1813-1887) is one of the least poorly-known German explorers, geographers and biologists of the 19"' century. Between 1836 and 1860, expeditions led him to Algeria, the Caucasus Region, as well as to North-, Central- and South-America. Beside his important scientific contributions to biology, geography and ethnogra- phy he also collected large numbers of plant and animal specimens. The collected material is scattered among several European museums and university collections because Wagner only obtained a permanent position after his last voyage. Prior to this he donated his material to experts, flinding societies or the institutions where he was a student or in whose collections he worked. The present article is a first contribution towards a review of the herpetological collections made by Moritz Wagner, which includes type material of several amphibians and reptiles. -

Enzymatic and Pro-Inflammatory Activities of Bothrops Lanceolatus

Enzymatic and Pro-Inflammatory Activities of Bothrops lanceolatus Venom: Relevance for Envenomation Marie Delafontaine, Isadora Maria Villas-Boas, Laurence Mathieu, Patrice Josset, Joël Blomet, Denise V. Tambourgi To cite this version: Marie Delafontaine, Isadora Maria Villas-Boas, Laurence Mathieu, Patrice Josset, Joël Blomet, et al.. Enzymatic and Pro-Inflammatory Activities of Bothrops lanceolatus Venom: Relevance for Enveno- mation. Toxins, MDPI, 2017, 9 (8), pp.244. 10.3390/toxins9080244. hal-01590607 HAL Id: hal-01590607 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01590607 Submitted on 19 Sep 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License toxins Article Enzymatic and Pro-Inflammatory Activities of Bothrops lanceolatus Venom: Relevance for Envenomation Marie Delafontaine 1, Isadora Maria Villas-Boas 2, Laurence Mathieu 1, Patrice Josset 3, Joël Blomet 1 and Denise V. Tambourgi 2,* ID 1 Prevor Laboratory, Moulin de Verville, Valmondois 95760, France; [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (J.B.) 2 Immunochemistry Laboratory, Butantan Institute, São Paulo 05503-900, Brazil; [email protected] 3 Trousseau Hospital, Paris 75012, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-11-2627-9722 Academic Editor: Syed A. -

Iguana 12.2 B&W Text

VOLUME 12, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2005 ONSERVATION AUANATURAL ISTORY AND USBANDRY OF EPTILES IC G, N H , H R International Reptile Conservation Foundation www.IRCF.org GLENN MITCHELL Anegada or Stout Iguana (Cyclura pinguis) (see article on p. 78). JOHN BINNS RICHARD SAJDAK A subadult Stout Iguana (Cyclura pinguis) awaiting release at the head- Timber Rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) reach the northernmost extent starting facility on Anegada (see article on p. 78). of their range on the bluff prairies in Wisconsin (see article on p. 90). This cross-stitch was created by Anne Fraser of Calgary, Alberta from a photograph of Carley, a Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi) at the Captive Breeding Facility on Grand Cayman. The piece, which measures 6.8 x 4.2 inches, uses 6,100 stitches in 52 colors and took 180 hours to complete. It will be auctioned by the IRCF at the Daytona International Reptile Breeder’s Expo on 20 August 2005. Profits from the auction will benefit conser- vation projects for West Indian Rock Iguanas in the genus Cyclura. ROBERT POWELL ROBERT POWELL Red-bellied or Black Racers (Alsophis rufiventris) remain abundant on Spiny-tailed Iguanas (Ctenosaura similis) are abundant in archaeologi- mongoose-free Saba and St. Eustatius, but have been extirpated on St. cal zones on the Yucatán Peninsula. This individual is on the wall Christopher and Nevis (see article on p. 62). around the Mayan city of Tulúm (see article on p. 112). TABLE OF CONTENTS IGUANA • VOLUME 12, NUMBER 2 • JUNE 2005 61 IRCFInternational Reptile Conservation Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS RESEARCH ARTICLES Conservation Status of Lesser Antillean Reptiles . -

Is the Martinique Ground Snake Erythrolamprus Cursor Extinct?

Is the Martinique ground snake Erythrolamprus cursor extinct? S TEPHANE C AUT and M ICHAEL J. JOWERS Abstract The Caribbean Islands are a biodiversity hotspot throughout Martinique during the th and th centuries where anthropogenic disturbances have had a significant (Moreau de Jonnès, ). It was last observed on the impact, causing population declines and extinction of en- Martinique mainland in , when a single individual demic species. The ground snake Erythrolamprus cursor is was caught near Fort-de-France. There are two potential a dipsadid endemic to Martinique; it is categorized as reasons for its decline: people may have mistaken it for Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List and is known the venomous lancehead Bothrops lanceolatus, which may only from museum specimens. The snake was common on have led to its eradication, and the small Indian mongoose Martinique during the th and th centuries but there Herpestes javanicus auropunctatus, an invasive predator, have been no reliable sightings since , suggesting it was introduced to the West Indies at the end of the th cen- may have gone extinct, probably as a result of the introduc- tury, resulting in declines and extirpations of reptile species tion of the small Indian mongoose Herpestes javanicus aur- (Henderson, ). opunctatus. However, the islet known as Diamond Rock, To the south-west of Martinique, c. km from the coast, south-west of Martinique, is mongoose-free and the last re- lies a volcanic islet (spanning . ha, with a maximum ele- ported sighting of E. cursor there was in . The islet was vation of m; Fig. a; Plate ) known as Diamond Rock. -

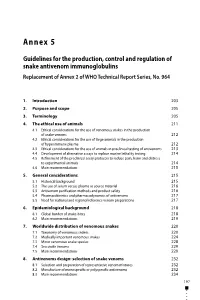

Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No

Annex 5 Guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 964 1. Introduction 203 2. Purpose and scope 205 3. Terminology 205 4. The ethical use of animals 211 4.1 Ethical considerations for the use of venomous snakes in the production of snake venoms 212 4.2 Ethical considerations for the use of large animals in the production of hyperimmune plasma 212 4.3 Ethical considerations for the use of animals in preclinical testing of antivenoms 213 4.4 Development of alternative assays to replace murine lethality testing 214 4.5 Refinement of the preclinical assay protocols to reduce pain, harm and distress to experimental animals 214 4.6 Main recommendations 215 5. General considerations 215 5.1 Historical background 215 5.2 The use of serum versus plasma as source material 216 5.3 Antivenom purification methods and product safety 216 5.4 Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antivenoms 217 5.5 Need for national and regional reference venom preparations 217 6. Epidemiological background 218 6.1 Global burden of snake-bites 218 6.2 Main recommendations 219 7. Worldwide distribution of venomous snakes 220 7.1 Taxonomy of venomous snakes 220 7.2 Medically important venomous snakes 224 7.3 Minor venomous snake species 228 7.4 Sea snake venoms 229 7.5 Main recommendations 229 8. Antivenoms design: selection of snake venoms 232 8.1 Selection and preparation of representative venom mixtures 232 8.2 Manufacture of monospecific or polyspecific antivenoms 232 8.3 Main recommendations 234 197 WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization Sixty-seventh report 9.