An Outbreak of Fall Armyworm in Indian Subcontinent : a New Invasive Pest on Maize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P2252 Corn Insect Identification

Corn Insect Identification Guide Photo Credits 4,6,8,10,17,18,19,29,33,34,36,38,39,41,42,44,45- Angus Catchot, Mississippi State University 12,20,21,22,23,26,27,28,35,37,43,47– Scott Stewart, The University of Tennessee 1,27,9,11,13,14,15,24,31-Chris Daves, Mississippi State University 16, 32- Blake Layton, Mississippi State University 48, 49-Fangneng Huang, Louisiana State University 30-Marlin Rice, Iowa State University 25- Jeff Gore, Mississippi State University 5- Ric Bessin, University of Kentucky Entomology Figures 1-13. Wire Worms (1), White Grubs (2), Seedcorn Maggot (3), Corn Root Aphid (4), Corn Leaf Aphids (5), Greenbugs (6), Southern Corn Rootworm Damage (7), Southern Corn Rootworm Immature (8), Southern Corn Rootworm Adult (9), Dead Heart Plant From Southern Corn Rootworm Feeding (10), Slug (11), Thrips Injury (12), Black Cutworm and Damage (13). Figures 14-25. Cutworm Climbing Young Plant (14), Chinch Bug Immatures (15), Chinch Bug Adult (16), Sugarcane Beetle (17), Sugarcane Beetle Damage (18), Stunted Plants from Sugarcane Beetle (19), Bill- bug (20), Southwestern Corn Borer Eggs (21), Southwestern Corn Borer Leaf Etching (22), Southwestern Corn Borer Larva (23), Southwestern Corn Borer Stalk Damage (24), Overwintering Southwestern Corn Borer Larva (25). Figures 26-37. Girdled Stalk by Southwestern Corn Borer (26), Southwestern Corn Borer Moth (27), Eu- ropean Corn Borer Larva (28), Ear Shank Tunneling by European Corn Borer (29), Female and Male Eu- ropean Corn Borer Moths (30), Sugarcane Borer Tunneling Stalk (31), Lesser Cornstalk Borer Larva (32), True Armyworm Larva (33), Fall Armyworm Larva (34), Fall Armyworm Damaged Whorl (35), Fall Army- worm Larvae in Ear Showing Inverted Y on Head Capsule (36), Corn Earworm Egg on Silks (37). -

Relationship Between Corn Stalk Strength and Southwestern Corn Borer Penetration

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2009 Relationship between corn stalk strength and southwestern corn borer penetration Bradley Kyle Gibson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Gibson, Bradley Kyle, "Relationship between corn stalk strength and southwestern corn borer penetration" (2009). Theses and Dissertations. 3766. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/3766 This Graduate Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CORN STALK STRENGTH AND SOUTHWESTERN CORN BORER PENETRATION By Bradley Kyle Gibson A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Agricultural Life Sciences in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Mississippi State, Mississippi May 2009 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CORN STALK STRENGTH AND SOUTHWESTERN CORN BORER PENETRATION By Bradley Kyle Gibson Approved: _________________________________ _________________________________ Fred R. Musser W. Paul Williams Assistant Professor of Entomology Supervisory Research Geneticist (Plants) (Director of Thesis) United States Department of Agriculture (Committee Member) _________________________________ -

Bt Corn (Lepidoptera) Resistance Monitoring Studies

Bt Corn (Lepidoptera) Resistance Monitoring Studies Bt corn registrants are required to submit annual resistance monitoring reports for the following lepidopteran target pests: • European corn borer (ECB); • corn earworm (CEW); and • southwestern corn borer (SWCB). These reports have generally addressed two objectives: • bioassay results of pest populations sampled from random locations in the Corn Belt; and • the results of investigations into unexpected pest damage to Bt corn fields. The table below lists the resistance monitoring reports received by EPA. Individual studies are generally identified by MRID numbers, though not all reports have assigned MRID numbers. Notes: ECB = European corn borer (Ostrinia nubilalis) CEW = corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea) SWCB = southwestern corn borer (Diatraea grandiosella) FAW = fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) Public Summary Available in IRM docket? Year Insect(s) Toxin(s) MRID# [information to be added when available] 1996 ECB Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac 443437-02, 444756-01 ECB, CEW, 1997 Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac 444754-01, 444756-01 SWCB ECB, CEW, 1998 Cry1Ab 447753-01 SWCB 1999 ECB, SWCB Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac 450369-02 1999 CEW Cry1Ab 450568-01 1999 FAW Cry1Ab 454381-01 2000 ECB, SWCB Cry1Ab 453205-02 Public Summary Available in IRM docket? Year Insect(s) Toxin(s) MRID# [information to be added when available] 2000 CEW Cry1Ab No report submitted 2000 FAW Cry1Ab 456663-01 No MRID assigned 2001 ECB Cry1Ab (Siegfried and Spencer 2001a) No MRID assigned 2001 ECB Cry1F (Siegfried and Spencer 2001b) No MRID assigned 2001 SWCB Cry1Ab (Song et al. 2001a) No MRID assigned 2001 SWCB Cry1F (Song et al. 2001b) No MRID assigned 2001 CEW Cry1Ab (Custom Bio-Products 2002a) No MRID assigned 2001 CEW Cry1F (Custom Bio-Products 2002b) No MRID assigned 2002 ECB Cry1Ab (Siegfried and Spencer 2002a) No MRID assigned 2002 ECB Cry1F (Siegfried and Spencer 2002b) No MRID assigned 2002 SWCB Cry1Ab (Song et al. -

Southwestern Corn Borer Damage and Aflatoxin Accumulation in a Diallel Cross of Maize

J. Genet. & Breed. 56: 165-169 (2002) Southwestern corn borer damage and aflatoxin accumulation in a diallel cross of maize W.P. Williams, F.M. Davis, -G.L. Windham and P.M. Buckley USDA-ARS Corn Horst Plant Resistance Research Unit, Box 9555, • Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA. Fax: (662) 325-8441. • Received September 18, 2001 ABSTRACT Southwestern corn borer, Diatraea grandiosella Dyar, is a serious pest of maize, Zea mays L., in the southern USA. When plants are infested during and after anthesis, larvae feed on the husks and developing cars before tunneling into the stalk. Larval feeding also provides potential sites for fungi to enter developing ears. Aflatoxin, produced by the fungus Aspergillus flavus Link: Fr, is a potent carcinogen, and its presence at levels exceeding 20 ng g restricts maize from interstate commerce. Aflatoxin contamination is a chronic problem in maize produced in the southern USA. Little is cur- rently known about the value of resistance to southwestern corn borer in reducing aflatoxin accu- mulation. This investigation was undertaken to compare aflatoxin accumulation in crosses among in- bred crosses with different levels of southwestern corn borer resistance and to study the importance of general and specific combining ability in the inheritance of resistance to southwestern corn bor- er and aflatoxin accumulation in an eight-parent diallel cross. Our results indicated that general com- bining ability was a highly significant source of variation in the inheritance of resistance to stalk tun- neling and ear damage by southwestern corn borer and resistance to aflatoxin accumulation. Stalk tunneling, ear damage, and aflatoxin accumulation were lowest in hybrids with the inbred line MP496 as a parent. -

THE SOUTHWESTERN CORN BORER in ARKANSAS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor

THE SOUTHWESTERN CORN BORER IN ARKANSAS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By LAWRENCE HUBERT ROLSTON, A.B., M.S. The Ohio State University 1955 Approved by: Department of Zoology and Entomology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is particularly indebted to; Dr. Ralph H. Davidson, of The Ohio State University, and the staff of the Department of Entomology at the University of Arkansas for suggestions during the course of this investigation and critical reading of the manuscript; to student assist ants Messrs. Philip Callahan, James Hawkins and Ralph Mayes; to Mr. Henry Vose, Manager of the substation at Van Buren for his cooperation; and to Dr. Lloyd 0. Warren for the photography. A special expression of gratitude is due the many farmers who tolerated trespassing, mutilation of their corn and other nuisances. ii TABLE OP CONTENTS Introduction ......................................... 1 Review of Literature Dlatraea species In the United States ............ 2 History and distribution ........................ 3 Life and Seasonal History Life history .................................... 8 Seasonal history ................... 8 Description of Injury ................................ 13 Adult Description ..................................... 17 B e h a v i o r ........................................ l8 Emergence ....................................... 20 Longevity ....................................... 20 Proportion of sexes ............................ -

Post-Embryonic Development of the Reproductive System of the European Corn Borer, Ostrinia Nubilalis (Hübner) John Ackland Jones Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1973 Post-embryonic development of the reproductive system of the European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner) John Ackland Jones Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Jones, John Ackland, "Post-embryonic development of the reproductive system of the European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner) " (1973). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 4947. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/4947 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

The Southwestern Corn Borer and Its Control

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Bulletins Experiment Station (MAFES) 5-1-1969 The Southwestern corn borer and its control C. A. Henderson Frank M. Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/mafes-bulletins Recommended Citation Henderson, C. A. and Davis, Frank M., "The Southwestern corn borer and its control" (1969). Bulletins. 140. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/mafes-bulletins/140 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station (MAFES) at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -) ^ BULLETIN 773 MAY 1969 The Southwestern Corn Borer And fts Control By C. A. HENDERSON and FRANK M DAVIS Figure 1. Known distribution of the southwestern corn borer in the United States. Mississippi State University AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION JAMES MMvritci. MfcMORlAL j UBRARY STATE COLLEGE t MISSISSIPPI In Cooperation With The Entomology Research Division Agr. Res. Ser. U.S.D.A: MISSISSIPPI STATE UNIVERSITY . ) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Page List of common and scientific Natural enemies 13 names of insects discussed 2 Larvae mistaken for the south- Description and habits 3 western corn borer 14 Damage __ 7 Corn earworm 14 Control -- 10 Fall armyworm 15 Adjusting planting dates 10 Southearn cornstalk borer 15 Chemical control on corn . 10 European corn borer 16 Equipment for applying insecticide/; 12 Sugarcane borer 16 Cultural practices for control 13 Summary 16 COMMON AND SCIENTIFIC NAMES OF INSECTS DISCUSSED Common Name Scientific Name A mite Caloglyphus sji. -

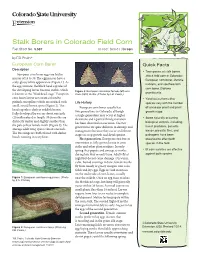

Stalk Borers in Colorado Field Corn Fact Sheet No

Stalk Borers in Colorado Field Corn Fact Sheet No. 5.537 Insect Series|Crops by F.B. Peairs* European Corn Borer Quick Facts Description • Two species of stalk borers European corn borer eggs are laid in attack field corn in Colorado: masses of 15 to 30. The egg masses have a European corn borer, Ostrinia scaly, glossy white appearance (Figure 1). As nubilalis; and southwestern the eggs mature, the black head capsules of corn borer, Diatraea the developing larvae become visible, which Figure 3: European corn borer female (left) and grandiosella. is known as the “blackhead stage.” European male (right) moths. (Photos by F.B. Peairs.) corn borer larvae are cream colored to • Yield losses from either pinkish caterpillars which are marked with Life History species vary with the number small, round brown spots (Figure 2). The European corn borer usually has of larvae per plant and plant head capsule is dark or reddish brown. two generations in Colorado, although growth stage. Fully developed larvae are about one inch a single generation may occur at higher (25 millimeters) in length. Male moths are • Some naturally occurring elevations and a partial third generation distinctly darker and slightly smaller than has been observed on occasion. The two biological controls, including the pale yellow female moth (Figure 3). The generations are quite different in damage and insect predators, parasitic average adult wing span is about one inch. management because they occur at different wasps, parasitic flies, and The forewings are buff colored with darker stages in crop growth and development. pathogens have been bands running in wavy lines. -

The Southwestern Corn Borer

TECHNICAL BULLETIN NO. 388 DECEMBER 1933 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE WASHINGTON, D.C. THE SOUTHWESTERN CORN BORER By E. G. DAVIS, aasistant entomologist \ J. R. IIORTON, etUomologist \ and C. H. GABLE,* E. V. WALTER, and R. A. BLANCHARD, associate entomologists, Division of Cereal and Forage Insects ; with technical descriptions by CARL. HEINRICH, entomologist. Division of Identification and Vlasmfication of Insects^ Bureau of Entomology^ CONTENTS Page Seasonal history—Continued Page Introduction I Effect of elevation and latitude on sea- History of the species 2 sonal history __. __ 24 Species of Diatraea in the United States 3 Life history and habits 25 Géographie distribution 3 The egg 25 Dissemination- 5 The larva 28 Artificial spread 5 The pupa... 35 Natural spread _- 5 Theaduit 37 Food plants _. fi Seasonal degree of infestation _ 40 Injury to the plant 7 Associated insects _ _ 40 Leaf injury _ 7 The corn ear worm 40 Bud injury 8 The fall army worm 41 Ear injury _ 8 The curlew bug 42 Stalk injury_ 10 Natural control 42 General damage 11 Physical and climatic deterrents. 42 Investigational methods _. 12 Natural enemies 44 Descriptions of the stages _ 13 Artificial control 49 The egg--_ 13 Delayed planting of corn to avoid borers. 49 The larva 14 Destruction of hibernating borers in The pupa... __ 16 stubble 52 Theaduit 18 Clean farming 67 Seasonal history 20 Ovicides and larvicides 57 First generation 22 Control recommendations 59 Second generation _ _ 23 Summary 69 Partial third generation 24 Literature cited 61 INTRODUCTION Severe damage to corn by the southwestern corn borer, Diatraea graruIioseUa Dyar,^ is more or less periodic in occurrence, but con- tinual yearly damage is greater than is generally realized, as the feeding in the stalk is hidden. -

Bt Corn and European Corn Borer K

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: Department of Entomology Entomology, Department of 1997 Bt corn and European corn borer K. R. Ostlie University of Minnesota - Twin Cities, [email protected] W. D. Hutchison R. L. Hellmich Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologyfacpub Part of the Entomology Commons Ostlie, K. R.; Hutchison, W. D.; and Hellmich, R. L., "Bt corn and European corn borer" (1997). Faculty Publications: Department of Entomology. 597. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologyfacpub/597 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: Department of Entomology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. http://www.extension.umn.edu/agriculture/corn/pest-management/bt-corn-and-european-corn-borer/ North Central Regional Publication 602, 1997 Bt corn and European corn borer Long-term success through resistance management Editors: K.R. Ostlie, W.D. Hutchison, & R. L. Hellmich. Authors and Contributors: J.F. Witkowski, J.L. Wedberg, K.L. Steffey, P.E. Sloderbeck, B.D. Siegfried, M.E. Rice, C.D. Pilcher, D.W. Onstad, C.E. Mason, L.C. Lewis, D.A. Landis, A.J. Keaster, F. Huang, R.A. Higgins, M.J. Haas, M.E. Gray, K.L. Giles, J.E. Foster, P.M. Davis, D.D. Calvin, L.L. Buschman, P.C. Bolin, B.D. Barry, D.A. Andow & D.N. Alstad. The editors express their appreciation to J.F. Witkowski for hosting key discussions on publication content. -

Weather Conditions and Maturity Group Impacts on the Infestation of First Generation European Corn Borers in Maize Hybrids in Croatia

plants Article Weather Conditions and Maturity Group Impacts on the Infestation of First Generation European Corn Borers in Maize Hybrids in Croatia Renata Bažok 1 , Ivan Peji´c 2, Maja Caˇcijaˇ 1,* , Helena Viri´cGašpari´c 1 , Darija Lemi´c 1 , Zrinka Drmi´c 3 and Martina Kadoi´cBalaško 1 1 Department of Agricultural Zoology, University of Zagreb Faculty of Agriculture, Svetošimunska Cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (H.V.G.); [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (M.K.B.) 2 Department of Plant Breeding, Genetics and Biometrics, University of Zagreb Faculty of Agriculture, Svetošimunska Cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] 3 Croatian Agency for Agriculture and Food, Plant Protection Center, VinkovaˇckaCesta 63c, 31000 Osijek, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +385-1-2393621 Received: 9 September 2020; Accepted: 16 October 2020; Published: 18 October 2020 Abstract: Overwintering success and weather conditions are the key factors determining the abundance and intensity of the attack of the first generation of European corn borers (ECB). The tolerance of maize to the 1st generation of ECB infestation is often considered to be connected with the maize maturity time. The aims of this research were (I) to examine the reactions of different maize FAO maturity groups in term of the damage caused by ECB larvae, (II) to analyze the influence of four climatic regions of Croatia regarding the damage caused by ECB larvae, and (III) to correlate observed damage between FAO maturity groups and weather conditions. First ECB generation damage has been studied in the two-year field trial with 32 different hybrids divided into four FAO maturity groups (eight per group) located at four locations with different climatic conditions. -

Southwestern Corn Borer

W196 Corn Insects Southwestern Corn Borer Scott Stewart, Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology Angela Thompson McClure, Associate Professor, Plant Sciences and Russ Patrick, Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology Classification and initially translucent white or yellowish with black Description: The spots on the body. Older larvae are creamy white southwestern corn and have more distinctive black spots. Larvae reach borer (Diatraea a maximum length of 1¼ inches. Pupae are dark grandiosella, brown, about ¾ inch long and located in the stalk Lepidoptera: or occasionally in ears or ear shanks. Overwintering Crambidae) is a well- larvae are light yellow-white and do not pupate until known caterpillar pest the following spring. Only faded spots are present on of corn. Its biology is overwintering larvae. similar to European corn borer. The moths Hosts, Life History and Distribution: Southwestern are dull white or buff- corn borer has relatively few hosts. Corn is the colored and about 1 primary host, but larvae are occasionally found on inch long, although sorghum and Johnsongrass. The SWCB is primarily their size can vary. distributed in the southern United States and Mexico. Southwestern corn borers (SWCB) lay flattened eggs Cold winter temperatures in most of the Midwestern in an overlapping mass reminiscent of fish scales. Corn Belt limit the northern range of this insect. Egg masses typically range from 2-6 eggs (whereas European corn borer egg masses normally have 8-40 A female moth only lives 5-7 days but may lay 250 eggs). Eggs are white when initially laid. They then eggs during her life span. Eggs take about five days develop red stripes within about 36 hours.