'Gleaning the Grain from the Threshing-Floor in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NZ Top 40 9 May 2006.Qxd 5/9/06 4:17 PM Page 1

NZ Top 40 9 May 2006.qxd 5/9/06 4:17 PM Page 1 CHART 1511 9 May 2006 www.nztop40.com TOP 40 SINGLES TOP 10 COMPILATIONS TOP 40 ALBUMS CATALOGUE No. CATALOGUE No. CATALOGUE No. LABEL LABEL LABEL TITLE/ARTIST DISTRIBUTOR TITLE/ARTIST DISTRIBUTOR TITLE/ARTIST DISTRIBUTOR THIS WEEK LAST WEEK WEEKS ON CHART THIS WEEK LAST WEEK WEEKS ON CHART THIS WEEK LAST WEEK WEEKS ON CHART 9852802 3595692 1 82876819912 1 18BEEP THE PUSSYCAT DOLLS FEAT. WILL.I.AM UNIVERSAL 1 18NOW THAT'S WHAT I CALL MUSIC 20 VARIOUS 4 EMI 1 NEW 1 10,000 DAYS TOOL SBME 3572140 9837828 82876714672 2 410BATHE IN THE RIVER MT RASKIL PS FEAT. HOLLIE SMITH EMI 2 27WAITING FOR THE WEEKEND VARIOUS 1 UNIVERSAL 2 NEW 1 PEARL JAM PEARL JAM 1 SBME 82876827172 3466222 RR80882 3 26I'M IN LUV (WIT A STRIPPER) T-PAIN FEAT. MIKE JONES SBME 3 44MEMORIES ARE MADE OF THIS VOL 3 VARIOUS 1 EMI 3 131ALL THE RIGHT REASONS NICKELBACK 3 ROADRUNNER/UNIVERSAL 3648400 5101139972 82876812762 4 NEW 1 DROWN BLINDSPOTT CAPITOL/EMI 4 NEW 1 ACOUSTIC LOVE SONGS VARIOUS 1 WEA/WARNER 4 13 2 THE VERY BEST OF ROY ORBISON 1 SBME 99729 5101139952 9871823 5 73IF IT'S COOL NESIAN MYSTIK BOUNCE/UNIVERSAL 5 34BROKEN DREAMS II VARIOUS 1 WEA/WARNER 5 NEW 1 THE ITALIAN PATRIZIO BUANNE UNIVERSAL 9850564 3641662 7567837525 6 59PUMP IT BLACK EYED PEAS UNIVERSAL 6 72I LOVE MUM VARIOUS 1 EMI 6 241BACK TO BEDLAM JAMES BLUNT 7 WEA/WARNER 3567882 9837819 8602472 7 610PUT YOUR RECORDS ON CORINNE BAILEY RAE CAPITOL/EMI 7 52HIP HOP IV: THE COLLECTION VARIOUS UNIVERSAL 7 313EYE TO THE TELESCOPE KT TUNSTALL 1 VIRGIN/EMI 9852863 828768742012 -

Breath 2013 April 164 曲、11.4 時間、1.20 GB

1 / 6 ページ breath_2013_April 164 曲、11.4 時間、1.20 GB 名前 時間 アルバム アーティスト 1 You Go to My Head 7:07 After Hours Jeanne Lee & マル・ウォルドロン 2 I Could Write a Book 4:03 After Hours Jeanne Lee & マル・ウォルドロン 3 Every Time We Say Goodbye 5:10 After Hours Jeanne Lee & マル・ウォルドロン 4 We're In This Love Together 3:46 Breakin' Away アル・ジャロウ 5 Breakin' Away 4:14 Breakin' Away アル・ジャロウ 6 (Everybody) Get Up 4:38 Bridging the Gap Roger 7 You Should Be Mine 6:02 Bridging the Gap Roger 8 The Woman In You 5:41 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 9 Less 4:06 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 10 Two Hands of a Prayer 7:50 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 11 Please Bleed 4:38 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 12 Suzie Blue 4:29 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 13 Steal My Kisses 4:05 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 14 Burn to Shine 3:35 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 15 Show Me a Little Shame 3:44 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 16 Forgiven 5:17 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 17 Beloved One 4:04 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 18 In the Lord's Arms 3:06 Burn to Shine Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals 19 Contort Yourself 4:26 Buy James Chance & the Contortions 20 Tin Tin Deo 2:56 Calypso Blues The Kenny Clarke - Francy Boland Sextet 21 Please Don't Leave 4:11 Calypso Blues The Kenny Clarke - Francy Boland Sextet 22 Lush Life 4:30 Calypso Blues The Kenny Clarke - Francy Boland Sextet 23 The Man From Potter's -

Country Rednex

Country Rednex Cotton eye joe La musique country, ou simplement country, est un mélange de musiques traditionnelles développé principalement dans le Sud-est des États-Unis et dans les provinces maritimes du Canada dans les années 19201. Elle a des millions d'amateurs dans le monde et notamment aux États-Unis, au Canada et en Australie, mais reste assez peu connue en France . Le siège de la country se trouve à Nashville, dans le Tennessee, ville qui doit son surnom "Music-City" au grand nombre de studios d'enregistrement et à la qualité de ses musiciens Blues Ben Harper Walk away Le blues est un style musical vocal et instrumental, dérivé des chants de travail des populations afro-américaines apparues aux États-Unis courant XIXe siècle. C'est un style où le (la) chanteur(euse) exprime sa tristesse et ses déboires. Le blues a eu une influence majeure sur la musique populaire américaine, puisqu'il est à la source du jazz, du rhythm and blues, du rock and roll entre autres. Gospel Whitney houston Oh happy day Le gospel est un chant religieux chrétien, protestant d'origine, qui prend la suite des negro spirituals. Le gospel est incontestablement une révolte musicale contre une Amérique raciste. C'est une expression de la souffrance des noirs récemment émancipés, mais encore sous l'autorité blanche, particulièrement dans les États du Sud. Le gospel comporte des quartets vocaux et des chanteurs de renom. Funk Kool and the gang Celebration Le funk est une forme de musique afro-américaine apparue aux États-Unis à la fin des années 1950, et qui s'est développée au cours des années 1960 et années 1970. -

Robbie Williams Another Saturday Night

Classic Pop / Dance A little less conversation - Elvis Angels - Robbie Williams Let's dance - Chris Rea Another Saturday night - Sam Cook Let's groove tonight - Earth wind n fire Baby did a bad bad thing - Chris Isaac Let's stick together - Bryan Ferry Better be home soon - Crowded House Life is a rollercoaster - Ronan Keating Big Yellow Taxi - Counting Crows Lips of an Angel - Hinder Billy Jean - Michael Jackson Love foolosophy - Jamiroquai Black fingernails - Eskimo Joe love is in the air - John Paul Young Blame it the Boogie - Jacksons Love really hurts without you - Billy Ocean Born to be Alive - Patrick Hernandez Love shack - B52's Boys of Summer - The Ataris Love the one you're with - Luther Vandross Brandy - Looking Glass Make Luv - Room 5 Bright side of the road - Van Morrison Makes me wonder - Maroon 5 Breakfast at Tiffanys - Deep blue something Man I feel like a woman - Shania Twain Cable Car - The Fray New York - Eskimo Joe Can't get enough of you baby - smashmouth No such thing - John Mayer Catch my disease - Ben Lee Not in Love - Enrique Iglesius Celebration - Kool and the Gang On the Beach - Chris rea Chain Reaction - John Farnham One more time - Britney Spears Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol Play that funky music - Average white band Cheap Wine - Cold Chisel Pretty Vegas - INXS Cherry cherry - Neil Diamond Rehab - Amy Winehouse Choir Girl - Cold Chisel Save the last dance for me - Michael Buble Clocks - Coldplay Second Chance - Shinedown NEW Closing time - Semisonic September - Earth wind and fire Come undone - Robbie Williams -

Ben Harper & the Innocent Criminals

BEN HARPER & THE INNOCENT CRIMINALS AUSTRALIAN TOUR DATES RESCHEDULED TO NOVEMBER 2016 WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 3, 2016 – Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals and Live Nation today announce that the Call It What It Is Tour dates for Australia and New Zealand have been rescheduled for later this year. The band have released the following statement: To our great fans in Australia and New Zealand: Unfortunately we need to postpone our upcoming tour so that we can put the finishing touches on our new album. We can’t wait to see you in November/December. Until then, Much love, BHIC The rescheduled Australian tour dates are as follows: ‘ON THE STEPS’, OPERA HOUSE FORECOURT, SYDNEY TUESDAY NOVEMBER 22 (previously Wednesday March 2) THE RIVERSTAGE, BRISBANE THURSDAY NOVEMBER 24 (previously Saturday March 5) SIDNEY MYER MUSIC BOWL, MELBOURNE SATURDAY NOVEMBER 26 (previously Saturday March 12) AEC THEATRE, ADELAIDE SUNDAY NOVEMBER 27 (previously at Adelaide Entertainment Centre on Friday March 11) KINGS PARK & BOTANIC GARDEN, PERTH TUESDAY NOVEMBER 29* (previously Tuesday March 8) Tickets for all shows - except Adelaide - will be valid for the rescheduled show date without the need to exchange. Adelaide ticket holders: Ticketek will be in contact directly with details of the exchange. Patrons who are unable to attend the rescheduled dates may obtain a refund from the point of purchase. The relevant ticketing agent will be in contact to provide details of how to obtain refunds if required. New tickets for all shows are on sale now. For further information please visit: www.livenation.com.au Call It What It Is will be the band’s first new album in eight years. -

Ben Harper and Relentless7 White Lies for Dark Times Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ben Harper And Relentless7 White Lies For Dark Times mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Blues Album: White Lies For Dark Times Country: US Released: 2009 Style: Folk Rock, Alternative Rock, Hard Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1738 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1362 mb WMA version RAR size: 1626 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 245 Other Formats: AIFF TTA APE MP4 AAC RA TTA Tracklist Hide Credits Number With No Name 1 Bass – Jesse IngallsDrums, Tambourine – Jordan RichardsonGuitar – Jason MozerskySlide 3:05 Guitar, Vocals – Ben HarperWritten-By – B. Harper*, J. Mozersky* Up To You Now Bass, Electric Piano [Wurlitzer] – Jesse IngallsDrums, Shaker, Tambourine – Jordan 2 5:01 RichardsonGuitar, Organ [B-3] – Jason MozerskyGuitar, Vocals – Ben HarperWritten-By – B. Harper*, J. Mozersky* Shimmer & Shine Backing Vocals – C.C. White Bass – Jesse IngallsBass [Additional] – Juan NelsonDrums 3 3:06 [Additional] – Oliver CharlesDrums, Tambourine – Jordan RichardsonGuitar – Jason MozerskySlide Guitar, Vocals – Ben HarperWritten-By – Ben Harper Lay There & Hate Me Bass, Piano, Electric Piano [Wurlitzer], Backing Vocals, Synthesizer [Arp], Backing Vocals – Jesse IngallsDrums, Percussion, Vibraphone [Vibes], Backing Vocals – Jordan 4 4:14 RichardsonGuitar, Backing Vocals – Jason MozerskySlide Guitar, Vocals, Drums [Additional], Piano, Electric Piano [Wurlitzer], Backing Vocals – Ben HarperWritten-By – B. Harper*, J. Ingalls* Why Must You Always Dress In Black 5 Bass – Jesse IngallsDrums, Tambourine – Jordan RichardsonGuitar – Jason MozerskySlide 4:41 Guitar, Vocals – Ben HarperWritten-By – Ben Harper Skin Thin Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar, Piano – Jason MozerskyBass, Piano – Jesse IngallsDrums – 6 4:32 Jordan RichardsonSlide Guitar, Guitar [12-string Baritone], Vocals, Backing Vocals – Ben HarperWritten-By – Ben Harper Fly One Time Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar, Baritone Guitar [12-string], Mandolin [Electric] – Jason 7 4:12 MozerskyBass – Jesse IngallsDrums, Shaker, Tambourine – Jordan RichardsonGuitar, Vocals, Piano – Ben HarperWritten-By – B. -

Ben Harper and Charlie Musselwhite Nightclub

Ben Harper And Charlie Musselwhite Nightclub Posts about Carole King written by thedailyrecord. Mostrando entradas con la etiqueta Ben Harper. “It was heartwarming, because there’s a genuine affection for the Belly Up and the artists are able to support the club with these albums. Bobby Johnson - Get Up and Dance (2013) Funk, R&B, Soul | 320 kbps | MP3 | 148. We were so pleased to recieve the message that […] Do you like it? 16. Their first album, 2012’s Get Up! , spurred, at least in my mind at the time, comparisons to other blues and jazz artists such as John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters. It’s the coolest makeover on the record, enigmatic and slinky as its originator. El llegendari músic va pensar que tots dos havien de tocar junts. Su destino Hamburgo, donde todavía vive con ochentaytantos años. Protoje, 9 p. 15 Dec 2019 - New at #TopMusic 7 days (15 Dec): 'The Way It Used To Be' by Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross; 'Nightclub' by Ben Harper & Charlie Musselwhite;. Download Ben Harper With Charlie Musselwhite "Get Up!" Now:iTunes: http://smarturl. Ben Harper & Charlie Musselwhite "When I Go": When I leave here I'll have no place to go And it's much too late to change my name I'm gonna take y. 08/03/2018 - Ben Harper & Charlie Musselwhite @ The Gothic Theatre - Englewood, CO Ben Harper & Charlie Musselwhite played the Gothic Theatre off Broadway to a sold out crowd last night. Get Up! is an album by the American musicians Charlie Musselwhite and Ben Harper , their twenty-ninth and eleventh album, respectively. -

Using Popular Song Lyrics to Teach Character and Peace Education

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2007 Using popular song lyrics to teach character and peace education Stacy Shayne Corbett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Humane Education Commons, Music Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Corbett, Stacy Shayne, "Using popular song lyrics to teach character and peace education" (2007). Theses Digitization Project. 3246. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3246 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING POPULAR SONG LYRICS TO TEACH CHARACTER AND PEACE EDUCATION A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Education: Holistic and Integrative Education by Stacy Shayne Corbett March 2007 USING POPULAR SONG LYRICS TO TEACH CHARACTER AND PEACE EDUCATION A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Stacy Shayne Corbett March 2007 Approved by: Dr. Robert London, First Reader ____ Dr. Samuel Crowell,'Second Reader © 2007 Stacy Shayne Corbett ABSTRACT With an increasing emphasis on standardized test scores and more and more exposure to adult issues and violence, there is a growing need for peace education. As an adult, I have discovered the profound messages songwriters can convey to their audience. -

Grammy Award Winner Ben Harper to Present Will Botwin with Visionary Leadership Award at the T.J

For Immediate Release: GRAMMY AWARD WINNER BEN HARPER TO PRESENT WILL BOTWIN WITH VISIONARY LEADERSHIP AWARD AT THE T.J. MARTELL FOUNDATION 39TH NEW YORK HONORS GALA LATIN POP SINGER CHAYANNE TO PRESENT AFO VERDE WITH LIFETIME MUSIC INDUSTRY ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Tuesday, October 21, 2014 – Cipriani New York New York, New York – (October 6, 2014) – The T.J. Martell Foundation for Leukemia, Cancer and AIDS Research has announced Ben Harper as presenter For Will Botwin who will receive the Visionary Leadership Award at this year’s highly anticipated T.J. Martell Foundation 39th New York Honors Gala to be held at Cipriani in New York on Tuesday, October 21, 2014. The foundation has also announced that Chayanne will present the LiFetime Music Industry Achievement Award to AFo Verde. Singer/Songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Ben Harper plays an eclectic mix oF blues, Folk, soul, reggae and rock music. His guitar playing is legendary amidst the music industry and his Fan base spans several continents. Harper is a three-time Grammy Award winner including his wins for Best Pop Instrumental Performance (2005), Best Traditional Soul Gospel Album (2005) and Best Blues Album in 2014. Latin pop singer Chayanne is not only a singer but also a composer and actor. As a solo artist, Chayanne has released 21 solo albums and sold over 30 million albums worldwide. He has acted in several soap operas and starred in the comedy series Generaciones. He also starred as a Cuban dancer along with Vanessa L. Williams in Dance with Me and made a guest appearance in the popular hit series Ally McBeal. -

Rock in Roma – Auditorium Parco Della Musica, Cavea

PRESS RELEASE N.6 BEH HARPER & The Innocent Criminals, IL 13 LUGLIO ROCK IN ROMA – AUDITORIUM PARCO DELLA MUSICA, CAVEA BEN HARPER & The Innocent Criminals 13 LUGLIO 2019 ROCK IN ROMA – AUDITORIUM PARCO DELLA MUSICA, CAVEA Prezzi biglietti PARTERRE STANDING € 50,00 + € 7,50 TRIBUNA CENTRALE € 60,00 + € 9,00 TRIBUNA MEDIANA € 55,00 + € 8,25 TRIBUNA LATERALE € 50,00 + € 7,50 TRIBUNA ALTA € 40,00 + € 6,00 Apertura porte: h 19.00 Inizio concerto: h 21:00 Prevendite: Rockinroma.com, Ticketone, Ticketmaster.it BEN HARPER torna in Italia con cinque nuovi grandi concerti: si esibirà al ROCK IN ROMA il prossimo 13 luglio, nella splendida cornice della Cavea dell’Auditorium Parco della Musica. I biglietti saranno disponibili a partire dalle ore 10.00 di venerdì 21 dicembre su rockinroma.com, www.ticketone.it e www.ticketmaster.it, e in tutti i punti vendita Ticketone dalle ore 10.00 di lunedì 24 dicembre. Dopo il suo album di debutto nel 1994, Welcome to the Cruel World, BEN HARPER ha pubblicato diversi album in studio di grande successo tra cui Fight For Your Mind, The Will to Live, Burn to Shine, Diamonds on the Inside, Lifeline (nominato ai GRAMMY) e Call It What It Is nel 2016. Tutti questi progetti hanno visto la collaborazione con The Innocent Criminals, band formata da Leon Mobley (percussioni), Juan Nelson (basso), Oliver Charles (batteria) e Jason Mozersky (chitarra). Il gruppo, che si è sempre esibito live assieme a Ben in giro per il mondo, si distingue per la diversità di generi musicali cui i vari componenti appartengono e che in una qualche maniera rende ciascun musicista complementare all’altro. -

Cena: 82.680,00 Rsd

Firma: Player Plus doo logoImage not found or type unknown Adresa: Svetogorska 9 Telefon: +381 11 3347 442 Fax: +381 11 3347 615 PIB: 106966344 E-mail: [email protected] PRO-JECTImage not found LP Georgeor type unknown Harrison Vinl Box PRO-JECT LP George Harrison Vinl Box Šifra: 12155 Kategorija prozivoda: Gramofoni Proizvođač: Pro-Ject Cena: 82.680,00 rsd. Presenting the magnificent George Harrison 16LP box set, Paul Rigby undertakes a detailed sound test and talks to the mastering engineers behind it, Lurssen Mastering’s Gavin Lurssen and Reuben Cohen George Harrison’s two CD/SACD box sets, covering his solo discography, have been on the shelf for some time (they were released in 2004 and 2014, respectively). I wondered if we’d ever see a vinyl box set of the same and, if it did appear, whether it would follow a similar two part template. Just the one, it appears because UMC has now released a single 16LP vinyl box set, The George Harrison Vinyl Collection. With the albums also being made available as standalone releases, the collection has been pressed on 180gm vinyl mastered from the original analogue tapes and cut at Capitol studios. Buyers will notice immediately that the slipcase box features…movement. Via the lenticular cover, showing two faces of Harrison as he matured during his solo years. The full contents list for the set includes: Wonderwall Music (1968), Electronic Sound (1969), All Things Must Pass (1970), Living In The Material World (1973), Dark Horse (1974), Extra Texture (1975), Thirty Three & 1/3 (1976), George Harrison (1979), Somewhere In England (1981), Gone Troppo (1982), Cloud Nine (1987), Live In Japan (1992) and Brainwashed (2002). -

Got Me Wrong

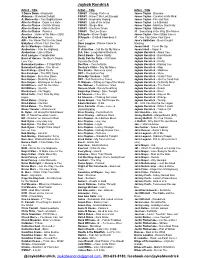

Jaykob Kendrick Artist - Title Artist - Title Artist - Title 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite CSN&Y - Change Partners James Taylor - Blossom Alabama – Dixieland Delight CSN&Y - Haven't We Lost Enough James Taylor - Carolina in My Mind A. Morissette – You Oughta Know CSN&Y - Helplessly Hoping James Taylor - Fire and Rain Alice in Chains - Down in a Hole CSN&Y - Lady of the Island James Taylor - Lo & Behold Alice in Chains - Got Me Wrong CSN&Y - Simple Man James Taylor - Machine Gun Kelly Alice in Chains - Man in the Box CSN&Y - Southern Cross James Taylor - Millworker Alice in Chains - Rooster CSN&Y - The Lee Shore JT - Something in the Way She Moves America – Horse w/ No Name ($20) D’Angelo – Brown Sugar James Taylor - Sweet Baby James Amy Winehouse – Valerie D’Angelo – Untitled (How does it JT - You Can Close Your Eyes AW – You Know That I’m No Good feel?) Jane's Addiction - Been Caught Babyface - When Can I See You Dave Loggins - Please Come to Stealing Arctic Monkeys - Arabella Boston Jason Isbell – Cover Me Up Audioslave - I Am the Highway D. Allan Coe - Call Me By My Name Jason Isbell – Super 8 Audioslave - Like a Stone D.A. Coe - Long-Haired Redneck Jaykob Kendrick - About You Avril Lavigne - Complicated David Bowie - Space Oddity Jaykob Kendrick - Barrelhouse Band of Horses - No One's Gonna Death Cab for Cutie – I’ll Follow Jaykob Kendrick - Fall Love You You into the Dark Jaykob Kendrick - Firefly Barenaked Ladies – If I had $1M Des’Ree – You Gotta Be Jaykob Kendrick - Kissing You Barenaked Ladies - One Week Destiny’s Child – Say My Name Jaykob Kendrick - Map Ben E King – Stand By Me Dire Straits - Romeo & Juliet Jaykob Kendrick - Medicine Ben Erickson - The BBQ Song DBT – Decoration Day Jaykob Kendrick - Muse Ben Harper - Burn One Down Drive-By Truckers - Outfit Jaykob Kendrick - Nuckin' Futs Ben Harper - Steal My Kisses DBT - Self-Destructive Zones Jaykob Kendrick – On the Good Foot Ben Harper - Waiting on an Angel D.