Firewood Utilisation and Its Implication on Trees Around Mopipi Village in Boteti Sub-District of Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating Land Use and Land Cover Change in the Gaborone Dam Catchment, Botswana, from 1984–2015 Using GIS and Remote Sensing

sustainability Article Evaluating Land Use and Land Cover Change in the Gaborone Dam Catchment, Botswana, from 1984–2015 Using GIS and Remote Sensing Botlhe Matlhodi 1,* , Piet K. Kenabatho 1 , Bhagabat P. Parida 2 and Joyce G. Maphanyane 1 1 Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Science, University of Botswana, P/Bag UB 00704 Gaborone, Botswana; [email protected] (P.K.K.); [email protected] (J.G.M.) 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, University of Botswana, P/Bag UB 0061 Gaborone, Botswana; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +267-355-5475 Received: 31 May 2019; Accepted: 7 August 2019; Published: 20 September 2019 Abstract: Land use land cover (LULC) change is one of the major driving forces of global environmental change in many developing countries. In this study, LULC changes were evaluated in the Gaborone dam catchment in Botswana between 1984 and 2015. The catchment is a major source of water supply to Gaborone city and its surrounding areas. The study employed Remote Sensing and Geographical Information System (GIS) using Landsat imagery of 1984, 1995, 2005 and 2015. Image classification for each of these imageries was done through supervised classification using the Maximum Likelihood Classifier. Six major LULC categories, cropland, bare land, shrub land, built-up area, tree savanna and water bodies, were identified in the catchment. It was observed that shrub land and tree savanna were the major LULC categories between 1984 and 2005 while shrub land and cropland dominated the catchment area in 2015. The rates of change were generally faster in the 1995–2005 and 2005–2015 periods. -

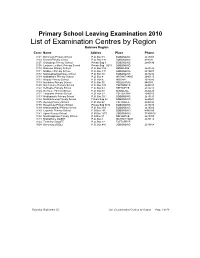

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

New List of Archaeologists 2019.Pdf

P Department of National Museum Monument and Art Gallery 331 Independence Avenue Gaborone, Botswana Private Bag 00114 Tel: (267) 3974616 (267) 3610400 Fax: (267) 3902797 Email: [email protected] Website: www.national- museum.gov.bw A LIST OF APPROVED ARCHAEOLOGISTS 2019 Our reference Dr Alfred Tsheboeng Dr Alinah Segobye P.O. Box 2789 University of Botswana Gaborone International Finance Park P/Bag 0022, Gaborone Plot 128,Kgale Court, Unit 8, Gaborone Tel: 3162036 Cel: 71374291 Tel: 3552281 Cel: 71625018 e-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Catrien Van Waarden Dr Nick Walker Marope Research Achilles Investments Pty Ltd P.O. Box 910, Francistown Gaborone Tel: 2414257 Cell: 71378415 Email: [email protected] [email protected] P. Sekgarametso-Modikwa Pena Monageng Archaeological Resources Management Services Ditso Archaeological Surveys P.O. Box 601271 P/Bag 0029, suit no 285 Gaborone Postnet Mogoditshane Tel: 3922289 cell: 71653378 Tel: 3552267 Cell: 71728860 Fax: 3922289 Fax: 3938757 Email: [email protected] Mr. O.J. NOKO Mr. Donald Mookodi Crystal Touch (Pty) Ltd Geoarch Investment Pty Ltd Postnet Kgale View P.O. Box 10111 P/Bag 351 suite 418 Gaborone Gaborone, Botswana Tel: (5442552 Cell: 71710397 Cell: 72202884 Fax: 3975566 Email: [email protected]/ 1 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Mr. Oscar Motsumi Nyatsego L. Baeletsi Watershed (Pty) Ltd Kgato-Go-Ya-Pele (Pty) Ltd P.O. Box 3347 P.O. Box 202850 Gaborone, Botswana Gaborone Tel: (09267) 316400/3699840 Tel/Fax: 3185133 Cel: 71676356 Cel: (09267) 71313089/74222285 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] motsumio@botsnet-bw Dr Susan O. -

Haina-Kalahari-Lodge-Directions.Pdf

DIRECTIONS GPS CO-ORDINATES Main Gate: Lodge: S 21° 00.006’ S 20° 56.966’ E 023° 41.085’ E 023° 40.684’ Campsite: Airfield: S 20° 59.310’ S 20° 57.081’ E 023° 41.905’ E 023° 40.209’ CONTACT DETAILS Lodge Phone: +267 683 0238 Email: [email protected] Reservations Phone: +27 21 421 8433 Website: www.haina.co.za HAINA KALAHARI LODGE From Maun towards Mopipi. The road passes Mopipi and carries Take the main road to Nata – turn right at about on towards Rakops. 23km past the police station at 50km out of Maun towards Makalamabedi. Drive on Rakops turn left on a dirt road, here you will find a sign for 18km (mind the sharp right crossing the Boteti board Haina Kalahari Lodge (please don’t turn left at river!) to the Vet fence gate. Go through the fence the signboard for the Central Kalahari Game Reserve and turn directly right (90 deg.) onto the cut line which is only about 5km past the police station). running South (mind the curb – take a wide turn). Carry on with this dirt road, after +/- 45km you will Continue on the cut line for 70 odd km and turn right find a gate this is Pfefodiafoka (some people refer again entering the gate at Kuke corner. #Take the to this gate as the Kuke Corner). Sign the register small loop around and drive west along the Northern and pass through the Pfefodiafoka Corner Veterinary border on CKGR for 20km. There is a sign for Haina Gate almost 20km, with the veterinary fence on you on the right. -

List of Schools Visited for Monitoring Visits

LIST OF SCHOOLS VISITED FOR MONITORING VISITS CENTRAL INSPECTORAL AREA LOCATION NAME OF SCHOOL MMADINARE Diloro Diloro MMADINARE Mmadinare Kelele MMADINARE Kgagodi Kgagodi MMADINARE Mmadinare Mmadinare MMADINARE Mmadinare Phethu Mphoeng MMADINARE Robelela Robelela MMADINARE Gojwane Sedibe MMADINARE Serule Serule MMADINARE Mmadinare Tlapalakoma BOTETI Rakops Etsile BOTETI Khumaga Khumaga BOTETI Khwee Khwee BOTETI Mopipi Manthabakwe BOTETI Mmadikola Mmadikola BOTETI Letlhakane Mokane BOTETI Mokoboxane Mokoboxane BOTETI Mokubilo Mokubilo BOTETI Moreomaoto Moreomaoto BOTETI Mosu Mosu BOTETI Motlopi Motlopi BOTETI Letlhakane Retlhatloleng Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boitshoko Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boswelakgomo Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Tebogo BOBIRWA Bobonong Bobonong BOBIRWA Gobojango Gobojango BOBIRWA Bobonong Mabumahibidu BOBIRWA Bobonong Madikwe BOBIRWA Mogapi Mogapi BOBIRWA Molalatau Molalatau BOBIRWA Bobonong Rasetimela BOBIRWA Semolale Semolale BOBIRWA Tsetsebye Tsetsebye 1 | P a g e MAHALAPYE WEST Bonwapitse Bonwapitse MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Leetile MAHALAPYE WEST Mokgenene Mokgenene MAHALAPYE WEST Moralane Moralane MAHALAPYE WEST Mosolotshane Mosolotshane MAHALAPYE WEST Otse Setlhamo MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye St James MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Tshikinyega MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Flowertown MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Mahalapye MHALAPYE EAST Matlhako Matlhako MHALAPYE EAST Mmaphashalala Mmaphashalala MHALAPYE EAST Sefhare Mmutle PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Sekgweng Goo-Sekgweng PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Tau Goo-Tau -

SABONET Report No 18

ii Quick Guide This book is divided into two sections: the first part provides descriptions of some common trees and shrubs of Botswana, and the second is the complete checklist. The scientific names of the families, genera, and species are arranged alphabetically. Vernacular names are also arranged alphabetically, starting with Setswana and followed by English. Setswana names are separated by a semi-colon from English names. A glossary at the end of the book defines botanical terms used in the text. Species that are listed in the Red Data List for Botswana are indicated by an ® preceding the name. The letters N, SW, and SE indicate the distribution of the species within Botswana according to the Flora zambesiaca geographical regions. Flora zambesiaca regions used in the checklist. Administrative District FZ geographical region Central District SE & N Chobe District N Ghanzi District SW Kgalagadi District SW Kgatleng District SE Kweneng District SW & SE Ngamiland District N North East District N South East District SE Southern District SW & SE N CHOBE DISTRICT NGAMILAND DISTRICT ZIMBABWE NAMIBIA NORTH EAST DISTRICT CENTRAL DISTRICT GHANZI DISTRICT KWENENG DISTRICT KGATLENG KGALAGADI DISTRICT DISTRICT SOUTHERN SOUTH EAST DISTRICT DISTRICT SOUTH AFRICA 0 Kilometres 400 i ii Trees of Botswana: names and distribution Moffat P. Setshogo & Fanie Venter iii Recommended citation format SETSHOGO, M.P. & VENTER, F. 2003. Trees of Botswana: names and distribution. Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 18. Pretoria. Produced by University of Botswana Herbarium Private Bag UB00704 Gaborone Tel: (267) 355 2602 Fax: (267) 318 5097 E-mail: [email protected] Published by Southern African Botanical Diversity Network (SABONET), c/o National Botanical Institute, Private Bag X101, 0001 Pretoria and University of Botswana Herbarium, Private Bag UB00704, Gaborone. -

Government Gazette

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Vol. XV, No. 66 GABORONE 4th November, 1977 CONTENTS Page Prorogation of Parliament — G.N. No. 630 of 1977............................................................................................... 892 Appointment of Session of Parliament — G.N. No. 631 of 1977........................................................................ 892 Appointment of General Registration Period — G.N. No. 632 of 1977........... 893 Establishment of Names, of Polling Stations — G.N. No. 633 ot 1977............................................................... 893 Application for Change in Establishment of School — G.N. No. 634 of 1977................................................ 894 Public Service Examinations — G.N. No. 635 of 1977.................................................. 895 Application to Register a School — G.N. No. 636 of 1977................................................................................... 896 Application for Authorization of Change of Name — G.N. No. 637 of 1977............................................................................................................................................... 896 G.N. No. 638 of 1977............................................................................................................................................... 897 Notice of Forfeiture of Land — G.N. No. 639 of 1977 (FirstPublication) ......................................................... 897 Treasury Bills — Issue of 28thOctober. 1977 — G.N.No. 640 of 1977........................................................... -

List of Cities in Botswana

List of cities in Botswana The following is a list of cities and towns in Botswana with population of over 3,000 citizens. State capitals are shown in boldface. Population Female Rank Name District Census District [1] Male Population 2001. Population 1. Gaborone South-East District Gaborone 186,007 91,823 94,184 2. Francistown North-East District Francistown 83,023 40,134 42,889 3. Molepolole Kweneng District Kweneng East 62,739 28,617 34,122 4. Serowe Central District Central Serowe/Palapye 52,831 25,400 27,431 5. Selibe Phikwe Central District Selibe Phikwe 49,849 24,334 25,515 6. Maun North-West District Ngamiland East 49,822 23,714 26,108 7. Kanye Southern District Ngwaketse 48,143 22,451 25,692 8. Mahalapye Central District Central Mahalapye 43,538 21,120 22,418 9. Mogoditshane Kweneng District Kweneng East 40,753 20,972 19,781 10. Mochudi Kgatleng District Kgatleng 39,349 18,490 20,859 11. Lobatse South-East District Lobatse 29,689 14,202 15,487 12. Palapye Central District Central Serowe/Palapye 29,565 13,995 15,570 13. Ramotswa South-East District South East 25,738 12,027 13,711 14. Moshupa Southern District Ngwaketse 22,811 10,677 12,134 15. Tlokweng South-East District South East 22,038 10,568 11,470 16. Bobonong Central District Central Bobonong 21,020 9,877 11,143 17. Thamaga Kweneng District Kweneng East 20,527 9,332 11,195 18. Letlhakane Central District Central Boteti 19,539 9,848 9,691 19. -

Public Primary Schools

PRIMARY SCHOOLS CENTRAL REGION NO SCHOOL ADDRESS LOCATION TELE PHONE REGION 1 Agosi Box 378 Bobonong 2619596 Central 2 Baipidi Box 315 Maun Makalamabedi 6868016 Central 3 Bobonong Box 48 Bobonong 2619207 Central 4 Boipuso Box 124 Palapye 4620280 Central 5 Boitshoko Bag 002B Selibe Phikwe 2600345 Central 6 Boitumelo Bag 11286 Selibe Phikwe 2600004 Central 7 Bonwapitse Box 912 Mahalapye Bonwapitse 4740037 Central 8 Borakanelo Box 168 Maunatlala 4917344 Central 9 Borolong Box 10014 Tatitown Borolong 2410060 Central 10 Borotsi Box 136 Bobonong 2619208 Central 11 Boswelakgomo Bag 0058 Selibe Phikwe 2600346 Central 12 Botshabelo Bag 001B Selibe Phikwe 2600003 Central 13 Busang I Memorial Box 47 Tsetsebye 2616144 Central 14 Chadibe Box 7 Sefhare 4640224 Central 15 Chakaloba Bag 23 Palapye 4928405 Central 16 Changate Box 77 Nkange Changate Central 17 Dagwi Box 30 Maitengwe Dagwi Central 18 Diloro Box 144 Maokatumo Diloro 4958438 Central 19 Dimajwe Box 30M Dimajwe Central 20 Dinokwane Bag RS 3 Serowe 4631473 Central 21 Dovedale Bag 5 Mahalapye Dovedale Central 22 Dukwi Box 473 Francistown Dukwi 2981258 Central 23 Etsile Majashango Box 170 Rakops Tsienyane 2975155 Central 24 Flowertown Box 14 Mahalapye 4611234 Central 25 Foley Itireleng Box 161 Tonota Foley Central 26 Frederick Maherero Box 269 Mahalapye 4610438 Central 27 Gasebalwe Box 79 Gweta 6212385 Central 28 Gobojango Box 15 Kobojango 2645346 Central 29 Gojwane Box 11 Serule Gojwane Central 30 Goo - Sekgweng Bag 29 Palapye Goo-Sekgweng 4918380 Central 31 Goo-Tau Bag 84 Palapye Goo - Tau 4950117 -

CITIES/TOWNS and VILLAGES Projections 2020

CITIES/TOWNS AND VILLAGES Projections 2020 Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Tel: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Toll Free: 0800 600 200 Private Bag F193, City of Francistown Botswana Tel. 241 5848, Fax. 241 7540 Private Bag 32 Ghanzi Tel: 371 5723 Fax: 659 7506 Private Bag 47 Maun Tel: 371 5716 Fax: 686 4327 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Cities/Towns And Villages Projections 2020 Published by Statistics Botswana Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Website: www.statsbots.org.bw E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Census and Demography Analysis Unit Tel: (267) 3671300 Fax: (267) 3952201 November, 2020 COPYRIGHT RESERVED Extracts may be published if source Is duly acknowledged Cities/Towns and Villages Projections 2020 Preface This stats brief provides population projections for the year 2020. In this stats brief, the reference point of the population projections was the 2011 Population and Housing Census, in which the total population by age and sex is available. Population projections give a picture of what the future size and structure of the population by sex and age might look like. It is based on knowledge of the past trends, and, for the future, on assumptions made for three components of population change being fertility, mortality and migration. The projections are derived from mathematical formulas that use current populations and rates of growth to estimate future populations. The population projections presented is for Cities, Towns and Villages excluding associated localities for the year 2020. Generally, population projections are more accurate for large populations than for small populations and are more accurate for the near future than the distant future. -

Prepaid Electricity Vendors

PREPAID ELECTRICITY VENDORS VENDOR NAME AREA LOCATION VENDOR NAME AREA LOCATION VENDOR NAME AREA LOCATION VENDOR NAME AREA LOCATION Tshwene Sereto General Dealer Bobonong Dinakedi Investments Lephephe LEPHEPHE Mogapi Molapowabojang MOLAPOWABOJANG CGB General Dealer Siviya SIVIYA Puma Filling Station Bobonong Tshwaragano Supermarket Bobonong BOBONONG Post Office Lerala LERALA Electric Affairs Molepolole Post Office Sojwe SOJWE Aksa Investments Borakalelo Kukie and Sons Investments Bobonong Mabego ’s Complex Letlhakane LETLHAKANE Post Office Sowa SOWA Post Office Bobonong Yash Cell Molepolole Post Office Letlhakane Nkitseng General Dealer Molepolole Tati Citi Shopping Centre Tati Siding Bodika Shop Bokaa Post Office Letlhakeng LETLHAKENG Nashimun Enterprises Lekgwapheng Super Force Tati Siding TATI SIDING Green Arrow General Dealer Pinyana Ward BOKAA Bidlop Difetlhamolelo Post Office Tati Town Post Office Bokaa Bismallah Thema Together As One Molepolole MOLEPOLOLE LM Store Peleng Dazzle Star Solutions Molepolole Bakgatla Supermarket Thamaga Savemore General Dealer Borolong (Along F/town Orapa Road) BOROLONG Western Supermarket Peleng MC Enterprises Molepolole Sego’s Shop Thamaga Post Office Charles Hill CHARLES HILL Flexi Shop Town Choppies Molepolole Changamire General Dealer Thamaga Choppies Cash & Carry Lobatse Kopa Dilalelo General Dealer Molepolole Neighbour Park General Dealer Thamaga THAMAGA Road Side General Dealer Dibete DIBETE Yash Cell Lobatse Agri Corner Molepolole Motshepi Butchery Thamaga Kilometre 4 Thamaga Post Office Digawana -

Jwaneng Water Supply

WATER UTILITIES CORPORATION TERMS OF REFERENCE FOR THE DESIGN REVIEW, TENDER DOCUMENTATION AND CONSTRUCTION SUPERVISION OF BOTETI SOUTHERN AND CENTRAL CLUSTER VILLAGES WATER SUPPLY SCHEME TENDER NO. WUC 028 (2017) Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 2. OBJECTIVES OF THE CONSULTANCY .............................................................................. 2 3. BACKGROUND ON PROJECT AREAS ............................................................................... 2 4. SCOPE OF WORK AND DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF WORKS ....................................... 4 4.1 SCOPE OF WORK ........................................................................................................... 4 4.2 DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF TASKS ............................................................................. 4 5. CONSULTING FIRM QUALIFICATION ................................................................................ 8 5.1 Consulting Firm Experience .............................................................................................. 8 5.2 Key Personnel ................................................................................................................... 8 6. DURATION AND TIME INPUT ........................................................................................... 11 7. DELIVERABLES ................................................................................................................. 12 8. REPORTING