An Embarrassment of Riches Also by Richard Grigg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociology of Religion, Lundscow, Chapter 7, Cults

Sociology of Religion , Sociology 3440-090 Summer 2014, University of Utah Dr. Frank J. Page Office Room 429 Beh. Sci., Office Hours: Thursday - Friday, Noon – 4:00-pm Office Phone: (801) 531-3075 Home Phone: (801) 278-6413 Email: [email protected] I. Goals: The primary goal of this class is to give students a sociological understanding of religion as a powerful, important, and influential social institution that is associated with many social processes and phenomena that motivate and influence how people act and see the world around them. The class will rely on a variety of methods that include comparative analysis, theoretical explanations, ethnographic studies, and empirical studies designed to help students better understand religion and its impact upon societies, global-international events, and personal well-being. This overview of the nature, functioning, and diversity of religious institutions should help students make more discerning decisions regarding cultural, political, and moral issues that are often influenced by religion. II. Topics To Be Covered: The course is laid out in two parts. The first section begins with a review of conventional and theoretical conceptions of religion and an overview of the importance and centrality of religion to human societies. It emphasizes the diversity and nature of "religious experience" in terms of different denominations, cultures, classes, and individuals. This is followed by overview of sociological assumptions and theories and their application to religion. A variety of theoretical schools including, functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory, sociology of knowledge, sociobiology, feminist theory, symbolic interactionism, postmodern and critical theory will be addressed and applied to religion. -

Golden Rules (Bill Maher)

localLEGEND Golden Rules Bill Maher may be one of the nation’s most outspoken cultural critics, but a part of him is still that innocent boy from River Vale. BY PATTI VERBANAS HE RULES FOR LIFE, according to Bill Maher, are unshakable belief in something absurd, it’s amazing how convoluted really quite simple: Treat your fellow man as you wish their minds become, how they will work backward to justify it. We to be treated. Be humane to all species. And, most make the point in the movie: Whenever you confront people about importantly, follow your internal beliefs — not those the story of Jonah and the whale — a man lived in a whale for three thrust upon you by government, religion, or conventional days — they always say, “The Bible didn’t say it was a whale. The thinking. If you question things, you cannot go too far wrong. Bible said it was a big fish.” As if that makes a difference. TMaher, the acerbic yet affable host of HBO’s Real Time, author of New Rules: Polite Musings from a Timid Observer, and a self-described What do you want viewers to take away from this film? “apatheist” (“I don’t know what happens when I die, and I don’t I want them to have a good time. It’s a comedy. Beyond that, I would care”), recently released his first feature film, Religulous, a satirical hope that the people who came into the theater who are already look at the state of world religions. Here he gets real with New Jersey sympathetic to my point of view would realize that there’s millions Life about faith, his idyllic childhood in River Vale, and why the of people like that — who I would call “rationalists” — and they best “new rule” turns out to be an old one. -

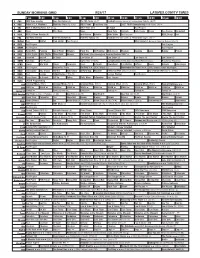

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

![<R2PX] 2^]Rtstb <XRWXVP]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2984/r2px-2-rtstb-xrwxvp-492984.webp)

<R2PX] 2^]Rtstb <XRWXVP]

M V 7>DB4>540AC7)Get a chic blueprint with no carbon footprint | 8]bXST A PUBLICATION OF | P L A N Y O U R N I G H T A T W W W. E X P R E S S N I G H T O U T. C O M | OCTOBER 3-5, 2008 | -- 5A44++ Weekend C74A>03F0AA8>AB --;Pbc]XVWc½bSTQPcTT]STSPUcTa C74A43B:8=B4G?42C0C>D675867C8=?78;;Hk ! 4g_aTbb½STPS[X]T5X]SX]ST_cW R^eTaPVTPcfPbWX]Vc^]_^bcR^\ <R2PX] 2^]RTSTb CHRIS O’MEARA/AP Evan Longoria hit two home runs in the Rays’ win. <XRWXVP] APhbA^[[)Longoria powers Losing ground, Republican Tampa to first playoff win | # writes off battleground state F0B78=6C>=k Republican presidential can- ATbRdT4UU^ac) Push to get didate John McCain conceded battleground Michigan to the Democrats on Thursday, GOP bailout passed gains steam | " officials said, a major retreat as he struggles to regain his footing in a campaign increas- 5^bbTcc2[dTb) Wreckage of ingly dominated by economic issues. These officials said McCain was pulling adventurer’s plane found | # staff and advertising out of the economically distressed Midwestern state. With 17 elec- 4=C4AC08=<4=C toral votes, Michigan voted for Democrat John Kerry in 2004, but Republicans had poured money into an effort to try to place it in their column this year. ?[PhX]V=XRT) The decision allows McCain’s resources Michael Cera acts to be sent to Ohio, Wisconsin, Florida and other more competitive states. But it also sweetly awk- means Obama can shift money to other ward .. -

JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Mono

EDITOR Daniel R. Langton ASSISTANT EDITOR Simon Mayers Title: Satire, Monotheism and Scepticism Author(s): JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Monotheism, Vol. 12 (2015), pp. 14-21 Published by: University of Manchester and Gorgias Press URL: http://www.melilahjournal.org/p/2015.html ISBN: 978-1-4632-0622-2 ISSN: 1759-1953 A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by SATIRE, MONOTHEISM AND SCEPTICISM Joshua L. Moss* ABSTRACT: The habits of mind which gave Israel’s ancestors cause to doubt the existence of the pagan deities sometimes lead their descendants to doubt the existence of any personal God, however conceived. Monotheism was and is a powerful form of Scepticism. The Hebrew Bible contains notable satires of Paganism, such as Psalm 115 and Isaiah 44 with their biting mockery of idols. Elijah challenged the worshippers of Ba’al to a demonstration of divine power, using satire. The reader knows that nothing will happen in response to the cries of Baal’s worshippers, and laughs. Yet, the worshippers of Israel’s God must also be aware that their own cries for help often go unanswered. The insight that caused Abraham to smash the idols in his father’s shop also shakes the altar erected by Elijah. Doubt, once unleashed, is not easily contained. Scepticism is a natural part of the Jewish experience. In the middle ages Jews were non-believers and dissenters as far as the dominant religions were concerned. With the advent of modernity, those sceptical habits of mind could be applied to religion generally, including Judaism. -

MDM Book Layout 12.14.18.Indd

CHRISTIANS MIGHT BE CRAZY ANSWERING THE TOP 7 OBJECTIONS TO CHRISTIANITY Mark Driscoll Christians Might Be Crazy © 2018 by Mark Driscoll ISBN: Unless otherwise indicated, scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright 2001 by Crossway Bibles a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All right reserved. All emphases in Scripture quotations have added by the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, Mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law. CONTENTS PREFACE: A PROJECT FOR SUCH A TIME AS THIS . 1 OBJECTION #1: INTOLERANCE . 25 “Jesus Freaks are intolerant bigots.” OBJECTION #2: ABORTION & GAY MARRIAGE . 47 “I have different views on social issues like abortion or gay marriage.” OBJECTION #3: POLITICS . 65 “I don’t like how some Christian groups meddle in politics.” OBJECTION #4: HYPOCRISY . 83 “Most Christians are hypocrites.” OBJECTION #5: EXCLUSIVITY . 101 “There are lots of religions, and I’m not sure only ONE has to be the right way.” OBJECTION #6: INEQUALITY. 119 “All people are not created equal in the Christian faith.” OBJECTION #7: SCRIPTURE . 135 “I don’t share the same beliefs that the Christian faith tells me I should.” CONCLUSION: REDEMPTION FROM RELIGION AND REBELLION . 155 NOTES . 173 PREFACE A PROJECT FOR SUCH A TIME AS THIS was hoping to release the findings of the massive project this book is based I upon some years ago, but a complicated season kept that from happening. -

The Last Laugh

THE LAST LAUGH A Tangerine Entertainment Production A film by Ferne Pearlstein Featuring: Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, Sarah Silverman, Robert Clary, Rob Reiner, Susie Essman, Harry Shearer, Jeffrey Ross, Alan Zweibel, Gilbert Gottfried, Judy Gold, Larry Charles, David Steinberg, Abraham Foxman, Lisa Lampanelli, David Cross, Roz Weinman, Klara Firestone, Elly Gross, Deb Filler, Etgar Keret, Shalom Auslander, Jake Ehrenreich, Hanala Sagal and Renee Firestone Directed, Photographed and Edited by: Ferne Pearlstein Written by: Ferne Pearlstein and Robert Edwards Produced by: Ferne Pearlstein and Robert Edwards, Amy Hobby and Anne Hubbell, Jan Warner 2016 / USA / Color / Documentary / 85 minutes / English For clips, images, and press materials, please visit our DropBox: http://bit.ly/1V7DYcq U.S. Sales Contacts Publicity Contacts [email protected] / 212 625-1410 [email protected] Dan Braun / Submarine Janice Roland / Falco Ink Int’l Sales Contacts [email protected] [email protected] / 212 625-1410 Shannon Treusch / Falco Ink Amy Hobby / Tangerine Entertainment THE LAST LAUGH “The Holocaust itself is not funny. There's nothing funny about it. But survival, and what it takes to survive, there can be humor in that.” -Rob Reiner, Director “I am…privy to many of the films that are released on a yearly basis about the Holocaust. I cannot think of one project that has taken the approach of THE LAST LAUGH. THE LAST LAUGH dispels the notion that there is nothing new to say or to reveal on the subject because this aspect of survival is one that very few have explored in print and no one that I know of has examined in a feature documentary.” -Richard Tank, Executive Director at the Simon Wiesenthal Center SHORT SYNOPSIS THE LAST LAUGH is a feature documentary about what is taboo for humor, seen through the lens of the Holocaust and other seemingly off-limits topics, in a society that prizes free speech. -

57Th Socal Journalism Awards

FIFTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL5 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA7 JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB th 57 ANNUAL SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 48 NOMINATIONS JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB 57TH SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS WELCOME Dear Friends of L.A. Press Club, Well, you’ve done it this time. Yes, you really have! The Los Angeles Press Club’s 57th annual Southern California Journalism Awards are marked by a jaw-dropping, record-breaking number of submissions. They kept our sister Press Clubs across the country, who judge our annual competition, very busy and, no doubt, very impressed. So, as we welcome you this evening, know that even to arrive as a finalist is quite an accomplishment. Tonight in this very Biltmore ballroom, where Senator (and future President) John F. Kennedy held his first news conference after securing his party’s nomination, we honor the contributions of our colleagues. Some are no longer with Robert Kovacik us and we will dedicate this ceremony to three of the best among them: Al Martinez, Rick Orlov and Stan Chambers. The Los Angeles Press Club is where journalists and student journalists, working on all platforms, share their ideas and their concerns in our ever changing industry. If you are not a member, we invite you to join the oldest organization of its kind in Southern California. On behalf of our Board, we hope you have an opportunity this evening to reconnect with colleagues or to make some new connections. Together we will recognize our esteemed honorees: Willow Bay, Shane Smith and Vice News, the “CBS This Morning” team and representatives from Charlie Hebdo. -

Reviewers' Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher's Religulous

Boise State University ScholarWorks Communication Faculty Publications and Department of Communication Presentations 4-1-2011 Bombing at the Box Office: Reviewers’ Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher’s Religulous Rick Clifton Moore Boise State University This is an electronic version of an article published in Journal of Media and Religion, Volume 10, Issue 2, 91-112. Journal of Media and Religion is available online at: http://www.informaworld.com. DOI: 10.1080/15348423.2011.572440 This is an electronic version of an article published in Journal of Media & Religion, Volume 10, Issue 2, 91-112. Journal of Media & Religion is available online at: http://www.informaworld.com. DOI: 10.1080/15348423.2011.572440 Bombing at the Box Office: Reviewers’ Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher’s Religulous Rick Clifton Moore Boise State University Abstract This paper examines reviewers’ reactions to Bill Maher’s documentary film Religulous as a way of beginning a discussion of media and religious hegemony. Hegemony theory posits that dominant ideology typically trumps contesting views, even when the latter do manage to leak through the system. Given this, one might expect that film reviewers serve as a second line of defense for entrenched worldviews. Here, however, a thematic analysis of reviews from major national newspapers reveals that critics provided only slight support to traditional religious views Maher challenges in his filmic plea for agnosticism. There is in the world of comedy a plot structure that has traditionally been referred to with the non-inclusive label, “Character gets hoisted with his own petard.” Most of us can envision this element by remembering the classic Warner Brothers Roadrunner and Coyote cartoons. -

Getting Beyond Religion As Science: "Unstifling" Worldview Formation in American Public Education

Getting Beyond Religion as Science: "Unstifling" Worldview Formation in American Public Education Barry P. McDonald* Abstract Since ancient times, Western civilization has witnessed a great debate over a simple but profound question: From whence did we come? Two major worldviews have dominated that debate: a theistic worldview holding that we, and the world in which we live, are the purposeful product of a supernatural creator; and a materialistic worldview holding that we are the product of unintelligent and random natural forces. This debate rose to the fore with Darwin’s publication of his theory of evolution and the development of the modern scientific establishment. In America, it initially took its most conspicuous form in efforts by creationists to ban the teaching of evolution in American public schools, and then to have creationism taught as science. After legal setbacks based on the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, that effort morphed into the intelligent design movement of the past couple of decades. That movement’s aim to gain a place in the science curriculum recently stalled with a court ruling that it was, like the creationists before it, attempting to teach religious concepts as science. Most recently, a notable group of scientists and atheists have reversed the trend of defending science against religious attacks and launched a very public and aggressive campaign against religion itself. Prominent scientists and other believers have responded with works attempting to reconcile science and faith. * Associate Professor of Law, Pepperdine University School of Law. J.D., Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois (1988). I would like to extend my grateful thanks and appreciation to Kent Greenawalt, Kurt Lash, and Steve Smith for some very helpful comments on this Article. -

Atheism, Agnosticism, and Nonbelief

ATHEISM, AGNOSTICISM, AND NONBELIEF: A QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE STUDY OF TYPE AND NARRATIVE By Christopher Frank Silver Ralph W Hood Jr Jim Tucker Professor Professor (Co-Chair) (Co-Chair) Valerie C. Rutledge David Rausch Professor Assistant Professor (Committee Member) (Committee Member) Anthony J. Lease A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of the College of Health, Education Dean of the Graduate School and Professional Studies ATHEISM, AGNOSTICISM, AND NONBELIEF: A QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE STUDY OF TYPE AND NARRATIVE By Christopher Frank Silver A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee August 2013 ii Copyright © 2013 By Christopher Frank Silver All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Extensive research has been conducted in exploration of the American religious landscape, however recently has social science research started to explore Nonbelief in any detail. Research on Nonbelief has been limited as most research focuses on the popularity of the religious “nones” or the complexities of alternative faith expressions such as spirituality. Research has been limited in exploring the complexity of Nonbelief or how non-believers would identify themselves. Most research assumes nonbelievers are a monolithic group with no variation such as Atheism or Agnosticism. Through two studies, one qualitative and one quantitative, this study explored identity of Nonbelief. Study one (the qualitative study) discovered that individuals have shared definitional agreement but use different words to describe the different types of Nonbelief. Moreover, social tension and life narrative play a role in shaping one’s ontological worldview. -

Human Social Evolution. the Foundational Works of Richard D

Alexander, Richard D. 2013. Religion, evolution, and the quest for global harmony. In K. Summers and B. Crespi (eds.), Human Social Evolution: The Foundational Works of Richard D. Alexander (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 384-425. RELIGION, EVOLUTION, AND THE QUEST FOR GLOBAL HARMONY Richard D. Alexander (Essay original to this volume) Introduction This essay is an effort to bring together aspects of human existence that have proceeded more or less separately, and even antithetically. They are (1) religion, in its principal components, and comprising the most widespread, divergent, and tenaciously authoritative defenses of morality; (2) organic evolution, as the science of all life; and (3) by far the most important and difficult, the effort (or at least, a hope or desire!) to work toward world-wide social harmony. It seems to me that the relationships of these and several other problems need to be considered together if humans in general are to moderate their hyper- competitiveness and hyper-patriotism, their theatrical attraction to violence, murder, and destruction, and the world’s continuing scourge of deadly conflicts. On the one hand is the universal and familiar coordination of personal and collective musings, beliefs, and efforts by which humans have for centuries sought to understand themselves and their associates; and on the other hand are the results and consequences of the more recently recognized and analyzed process of organic evolution. To every indication the evolutionary process has been responsible for the nature of all life, including the scope and diversity of human sociality and the consequences of the myriads of never-ending split- second and unexpected environmental changes that continually modify our performances by relentlessly racing across our human lifetimes.