Toward Social Material Flow Analysis: on the Usefulness of Boundary Objects in Urban Mining Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Apple Inc., 19, 178 B Basel Action Network, 116, 126 Basel

Index A E Apple Inc., 19, 178 End-of-life returns, 149 End-of-use returns, 149 B Environmental legislation, 86, 133, 144, 145 Basel Action Network, 116, 126 E-waste, 8, 82–91, 107, 108, 110, 115–120, Basel Convention, 83, 86, 117, 118 125–127, 129–131, 142 Bio-fuel, 7, 30, 31, 33–35 Extended producer responsibility, 88, 117, 119, Blood supply chain, 50, 51, 57, 58, 63–65, 121, 123, 127, 144, 202 67, 68 British, 180, 182, 202 F Brominated Fire Retardants (BFRs), 116 Feedstocks, 29, 35 Footprint, 8, 14, 26, 31, 35, 36, 38, 77, 78, 92–95, 113, 123, 127, 175–180, 182, 183, C 185–191, 195 C40, 3, 14, 16, 24 Fossil hydrocarbon fuels, 35 Cap and Trade, 176, 202 Carbon-dioxide, 1, 4, 7, 9, 10, 30, 39, 81, G 115, 193 GHG emissions, 9, 10, 14, 16, 19, 23, 175–180, CDP project, 14, 190, 191 182, 185–191 Certifier, 168–170, 173 GHG Protocol, 19, 177, 180, 182, 189 Chemicals, 39, 85, 118, 119, 121, 176, 179 Green building, 81, 82, 176, 185 Clinton Climate Initiative, 14 Green building history, 101 Closed-loop supply chain, 8, 133, 149, 163 Green Electronics Council (GEC), 123 Cloud computing, 92–95 Green IT, 74–77, 80, 81, 90, 91 CO2-eq., 10, 11, 14, 16, 19, 21, 23, 175, 182, Greenpeace, 4, 117, 127 186–188 Collective producer responsibility (CPR), H 130–132, 135, 142, 143 Health care, 39, 42, 49–51, 70, 71 Construction, 54, 60, 81, 82, 120, 171, 180, Herman Miller, 179, 180, 191 185 Hewlett-Packard, 73, 76, 125 Credibility, 166, 169, 171 I D ICLEI, 16 Data center, 75, 76, 78–80, 82, 92–95, 123, 185 India, 2, 4, 7, 11, 14, 25, 74, 78, 79, 81–86, 90, Dell, 25, 76, 121, 123, 125, 143, 186, 190 91, 94, 95, 110, 117–119 Disposition decision, 150–153, 156, 158, 160, Industrial ecology, 219 161, 163 In-house manufacturing, 132 T. -

Towards a Dynamic Assessment of Raw Materials Criticality: Linking Agent-Based Demand--With Material Flow Supply Modelling Approaches

This is a repository copy of Towards a dynamic assessment of raw materials criticality: linking agent-based demand--with material flow supply modelling approaches.. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/80022/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Knoeri, C, Wäger, PA, Stamp, A et al. (2 more authors) (2013) Towards a dynamic assessment of raw materials criticality: linking agent-based demand--with material flow supply modelling approaches. Science of the Total Environment, 461-46. 808 - 812. ISSN 0048-9697 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.001 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Towards a dynamic assessment of raw materials criticality: Linking agent-based demand - with material flow supply modelling approaches Christof Knoeri1, Patrick A. -

Examples in Material Flow Analysis

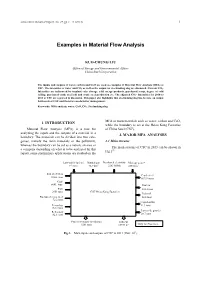

China Steel Technical Report, No. 27, pp.1-5, (2014) Kuo-Chung Liu 1 Examples in Material Flow Analysis KUO-CHUNG LIU Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs China Steel Corporation The inputs and outputs of water, carbon and CaO are used as examples of Material Flow Analysis (MFA) at CSC. The intensities of water and CO2 as well as the output for steelmaking slag are discussed. Current CO2- Intensities are influenced by in-plant coke storage, sold energy products, purchased scrap, degree of cold rolling, purchased crude steel/roll and crude steel production etc. The adjusted CO2- Intensities for 2010 to 2013 at CSC are reported in discussion. This paper also highlights that steelmaking slag has become an output bottleneck at CSC and therefore needs better management. Keywords: MFA analysis, water, CaO, CO2, Steelmaking slag MFA of main materials such as water, carbon and CaO, 1. INTRODUCTION while the boundary is set at the Hsiao Kang Factories Material Flow Analysis (MFA) is a tool for of China Steel (CSC). analyzing the inputs and the outputs of a material in a 2. MAJOR MFA ANALYSES boundary. The materials can be divided into two cate- gories, namely the main materials or the pollutants, 2.1 Main streams whereas the boundary can be set as a nation, an area or The main streams of CSC in 2013 can be shown in a company depending on what is to be analyzed. In this Fig.1(1). report, some preliminary applications are studied on the Low-sulfer fuel oil Natural gas Purchased electricity Makeup water* 9.3 tons 76.9 km3 2283 MWh 45554 m3 Iron ore/Pellets Crude steel 13066 tons 8693.6 tons Coal 6801 tons Coal tar Flux 205.2 tons 2951 tons CSC Hsiao Kang Factories Light oil Purchased scrap steel 54.8 tons 72.2 tons Liquid sulfur Ferroalloy 11.3 tons 132.1 tons Iron oxide powder Refractory 82.6 tons 28.7 tons Process residues (wet basis) Effluent 5281 tons 14953 m3 Only for Processes. -

Final Energy and Exergy Flow Portuguese Energy Sector

Primary-to-Final Energy and Exergy Flow s in the Portuguese Energy Sector 1960 to 2009 Dominique Anjo da Silva Thesis to obtain the M aster of Science Degree in Mechanical Engineering Examination Committee Chairperson: Prof. Dr. Mário Manuel Gonçalves da Costa Supervisor: Prof.ª Dr. ª Tânia Alexandra dos Santos Costa e Sousa Co-supervisor : Eng. André González Cabrera Honório Serrenho Members of the committee: Dr. Miguel Perez Neves Águas July 2013 1 Acknowledgements To Prof.ª Dr.ª Tânia Sousa for providing me the opportunity to elaborate my thesis on a topic I am passionate about. Her support and guidance throughout this thesis, as well as her openness to fruitful discussions, made this journey an enjoyable one. To Eng. André Serrenho, for his valuable knowledge and support. His expertise was proved fundamental to understand the workings of the IEA database and our discussions constituted a great learning opportunity. To the team at the EDP Foundation, in particular Eng. Pires Barbosa, Eng. Luis Cruz and Eng. Eduardo Moura for their technical expertise and valuable insight on the history of energy production in Portugal. Also to the team at the Electricity Museum in Lisbon, in particular Raquel Eleutério, for providing the opportunity to undertake a 6-month internship, which helped me develop a better technical, historical and societal understanding of the evolution of energy supply in Portugal from 1920 to the present. To Eng. Ana Pipio and Prof. Dr. José Santos-Victor, for their mentorship and support while I worked at the International Affairs team at Instituto Superior Técnico. To Prof. -

Permaculture

Permaculture What might it have to offer a green economist? Definition ‘The use of systems thinking and design principles that provide the organising framework for implementing a vision of consciously designed landscapes that mimic the relationships and patterns found in nature’ ‘Linear relationships are easy to think about: the more the merrier. Linear equations are solvable, which makes them suitable for textbooks. Linear systems have an important modular virtue: you can take them apart and put them together again—the pieces add up. Non-linear systems generally cannot be solved and cannot be added together . Non-linearity means that the act of playing the game has a way of changing the rules . That twisted changeability makes non-linearity hard to calculate, but it also creates rich kinds of behavior that never occure in linear systems’ James Gleick, Chaos: Making a New Science Traditional wisdom ‘Because of feedback delays within complex systems, by the time a problem becomes apparent it may be unnecessarily difficult to solve’ Translation: ‘A stitch in time saves nine’ ‘A diverse system with multiple pathways and redundancies is more stable and less vulnerable to external shock than a uniform system with little diversity’ Translation: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket Odum developed Howard Odum methods for tracking and measuring the flows of energy and nutrients through complex living systems Ways of understanding the links between flows of money and goods in society and the flows of energy in ecosystems ‘industrial man . eats potatoes largely made of oil’ Environment, Power and Society, 1971 ‘Odum proposed that a measurement of the amount of transformed solar energy embodied in any product of the biosphere or human society—for which he coined the term ‘emergy’—could provide a kind of ‘universal currency’ which would allow fair and accurate comparison of the human and natural contributions to any particular economic process. -

A Review of Circular Economy Development Models in China, Germany and Japan

Review A Review of Circular Economy Development Models in China, Germany and Japan Olabode Emmanuel Ogunmakinde School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, New South Wales 2308, Australia; [email protected], Tel: +61415815561 Received: 15 May 2019; Accepted: 2 July 2019; Published: 3 July 2019 Abstract: The circular economy (CE) concept is gaining traction as a sustainable strategy for reducing waste and enhancing resource efficiency. This concept has been adopted in some countries such as Denmark, Netherlands, Scotland, Sweden, Japan, China, and Germany while it is being considered by others including England, Austria, and Finland. The CE has been employed in the manufacturing, agricultural, textile, and steel industries but its implementation varies. It is against this backdrop that this study seeks to identify CE implementation in three pioneering countries (China, Japan, and Germany). A critical review and analysis of the literature was conducted. The results revealed enabling and core policies/laws for the development of the CE concept. It also identified the implementation structure of the CE in China, Germany, and Japan. In conclusion, the findings of this study are expected to serve as a guide for developing and implementing the CE concept in various sectors of the economy. Keywords: China; circular economy; Germany; implementation; Japan; resource efficiency; waste management 1. Background of the Study The linear economy is a waste-generating model. It is a system where resources become waste due to production and consumption processes [1]. The linear economy model is a “take-make-waste” approach [2,3] that extracts raw materials to manufacture products, which are disposed of by consumers after use. -

Industrial Ecology: a New Perspective on the Future of the Industrial System

Industrial Ecology: a new perspective on the future of the industrial system (President's lecture, Assemblée annuelle de la Société Suisse de Pneumologie, Genève, 30 mars 2001.) Suren Erkman Institute for Communication and Analysis of Science and Technology (ICAST), P. O. Box 474, CH-1211 Geneva 12, Switzerland Introduction Industrial ecology? A surprising, intriguing expression that immediately draws our attention. The spontaneous reaction is that «industrial ecology» is a contradiction in terms, something of an oxymoron, like «obscure clarity» or «burning ice». Why this reflex? Probably because we are used to considering the industrial system as isolated from the Biosphere, with factories and cities on one side and nature on the other, the problem consisting in trying to minimize the impact of the industrial system on what is «outside» of it: its surroundings, the «environment». As early as the 1950’s, this end-of-pipe angle was the one adopted by ecologists, whose first serious studies focused on the consequences of the various forms of pollution on nature. In this perspective on the industrial system, human industrial activity as such remained outside of the field of research. Industrial ecology explores the opposite assumption: the industrial system can be seen as a certain kind of ecosystem. After all, the industrial system, just as natural ecosystems, can be described as a particular distribution of materials, energy, and information flows. Furthermore, the entire industrial system relies on resources and services provided by the Biosphere, from which it cannot be dissociated. (It should be specified that .«industrial», in the context of industrial ecology, refers to all human activities occurring within the modern technological society. -

Achieving Energy Efficiency in Manufacturing: Organization, Procedures and Implementation

ACHIEVING ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN MANUFACTURING: ORGANIZATION, PROCEDURES AND IMPLEMENTATION _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science __________________________________________________________________ By SÂNDINA PONTE Dr. Bin Wu, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2011 © Copyright by Sândina Ponte 2011 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled ACHIEVING ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN MANUFACTURING: ORGANIZATION, PROCEDURES AND IMPLEMENTATION presented by Sândina Ponte, a candidate for the degree of master of science and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Bin Wu Professor James Noble Professor Hongbin Ma Thank you to my wonderful husband for the much needed motivation during those last few weeks. Thanks to Dr. Wu for supporting this project and being such a wonderful advisor and friend. Thanks to my managers Bernt Svens and Stefan Forsmark at ABB Inc. for believing in Energy Efficiency and the need for sustainable development. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks to my advisor, Dr. Bin Wu, for his contribution and support to my research. I also wish to thank Chatchai Pinthuprapa for his previous research on energy audits and web tool development. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................... -

Economy-Wide Material Flow Accounts Handbook – 2018 Edition

Economy-wide material flow accounts HANDBOOK 2018 edition Economy-wide material flow accounts flow material Economy-wide 2 018 edition 018 MANUALS AND GUIDELINES Economy-wide material flow accounts HANDBOOK 2018 edition Manuscript completed in June 2018 Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2018 © European Union, 2018 Reproduction is authorized for non-commercial purposes only, provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). Copyright for the photographs: Cover © Vladimir Wrangel/Shutterstock For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. For more information, please consult: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/about/policies/copyright Theme: Environment and energy Collection: Manuals and guidelines The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) only and should not be considered as representative of the official position of the European Commission Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein ISBN 978-92-79-88337-8 ISSN 2315-0815 doi: 10.2785/158567 Cat. No: KS-GQ-18-006-EN-N Preface Preface Economy-wide material flow accounts (EW-MFA) are a statistical accounting framework describing the physical interaction of the economy with the natural environment and the rest of the world economy in terms of flows of materials. -

An Overview of Istat's Environmental Accounting in the Light of Eu

An Overview of Istat’s Environmental Accounting in the Light of Eu Methodological Achievements Una visione d’insieme della contabilità ambientale dell’Istat alla luce di avanzamenti metodologici a livello europeo Cesare Costantino Istat, Direzione Centrale Contabilità Nazionale, Via Ravà 150, Roma, [email protected] Riassunto: La contabilità ambientale è una disciplina sviluppata nell’ambito degli organismi internazionali in relazione alle esigenze dello sviluppo sostenibile; essa trae origine dalla contabilità nazionale e si occupa in maniera sistematica e comprensiva del rapporto economia-ambiente. Una pluralità di conti, standardizzati in ambito europeo, consente di focalizzare aspetti specifici dell’interazione tra economia e ambiente, permettendo di confrontare i fatti economici e i fatti ambientali correlati attraverso un sistema coerente di definizioni e classificazioni. La produzione dell’Istat risponde alle esigenze conoscitive del paese e degli organismi internazionali, in particolare comunitari; in linea con la strategia europea per la contabilità ambientale, essa è a regime per quanto concerne la MFA, la NAMEA e l’EPEA, i conti a più elevata priorità. Keywords: economy-environment interaction, SEEA, DPSIR, MFA, NAMEA, EPEA. 1. Sustainable development strategy and environmental accounting Sustainable development calls for a variety of changes in the functioning of society. Innovations are needed involving different aspects such as e.g. production and consumption patterns and mechanisms for determining social choices. New statistical information is needed as well, to support decisions by institutions, enterprises and individuals, being clear that it is essential to integrate the institutional, economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. In Italy the importance of integrating economic and environmental aspects has been emphasized in the political agenda since the ’nineties. -

Industrial Ecology: Concepts and Approaches L

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 89, pp. 793-797, February 1992 Colloquium Paper This paper serves as an introduction to the following papers, which were presented at a colloquium entitled "Industrial Ecology, " organized by C. Kumar N. Patel, held May 20 and 21, 1991, at the National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC. Industrial ecology: Concepts and approaches L. W. JELINSKI*, T. E. GRAEDEL, R. A. LAUDISE, D. W. MCCALL, AND C. K. N. PATEL AT&T Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill, NJ 07974 ABSTRACT Industrial ecology is a new approach to the and gases, and produce wastes of their own. These industrial design of products and processes and the implemen- wastes are in turn food for other organisms, some of tation of sustainable manufacturing strategies. It is a concept which may convert the wastes into the minerals used in which an industrial system is viewed not in isolation from its by the primary producers, and some ofwhich consume surrounding systems but in concert with them. Industrial each other in a complex network of processes in which ecology seeks to optimize the total materials cycle from virgn everything produced is used by some organism for its material to finished material, to component, to product, to own metabolism. Similarly, in the industrial ecosys- waste product, and to ultimate disposal. To better characterize tem, each process and network of processes must be the topic, the National Academy of Sciences convened a collo- viewed as a dependent and interrelated part of a larger quium from which were derived a number of salient contribu- whole. -

Industrial Ecology: the Role of Manufactured Capital in Sustainability Helga Weisza,B,1, Sangwon Suhc, and T

SPECIAL FEATURE: INTRODUCTION Industrial Ecology: The role of manufactured capital in sustainability Helga Weisza,b,1, Sangwon Suhc, and T. E. Graedeld The lack of quantitative results over two aResearch Domain Transdisciplinary Concepts & Methods, Potsdam Institute for Climate decades ago was paralleled by a compelling Impact Research, 14473 Potsdam, Germany; bDepartment of Cultural History and Theory and c underrepresentation of methodological sug- Department of Social Sciences, Humboldt University Berlin, 10117 Berlin, Germany; Bren gestions. Among the few exceptions in those School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California, Santa Barbara, early papers were Ayres’ material flow anal- d CA 93106; and Center for Industrial Ecology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511 ysis of toxic heavy metals (17) and Duchin’s proposal to use economic input-output anal- ysis (18) to describe and analyze the meta- In 1992 PNAS presented a Special Feature with transition has increased in parallel, and the bolic connectedness among physical factors 22 contributions from a colloquium entitled technological and economic feasibility for such of production, industrial production, and “ ” Industrial Ecology, held at the National a transition has been demonstrated, especially consumptions sectors. Those two approaches Academy of Sciences of the United States in for the energy system (13, 14). have developed into core methods of Indus- Washington, DC (1). In these articles Industrial How did Industrial Ecology originally de- trial Ecology today (6, 19–25). The research Ecology was presented as an approach to un- fine its scope in what we now call sustain- articles included in the present Special Fea- derstand and ultimately optimize the total ma- ability science and what is its role today? If ture provide ample evidence for Industrial terial cycles of industrial processes (2).