The Matter of Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen Guinevere

Ingvarsdóttir 1 Hugvísindasvið Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskudeild Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir Kt.: 060389-3309 Supervisor: Ingibjörg Ágústsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 3 Abstract This essay is an attempt to recollect and analyze the character of Queen Guinevere in Arthurian literature and movies through time. The sources involved here are Welsh and other Celtic tradition, Latin texts, French romances and other works from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Malory’s and Tennyson’s representation of the Queen, and finally Guinevere in the twentieth century in Bradley’s and Miles’s novels as well as in movies. The main sources in the first three chapters are of European origins; however, there is a focus on French and British works. There is a lack of study of German sources, which could bring different insights into the character of Guinevere. The purpose of this essay is to analyze the evolution of Queen Guinevere and to point out that through the works of Malory and Tennyson, she has been misrepresented and there is more to her than her adulterous relation with Lancelot. This essay is exclusively focused on Queen Guinevere and her analysis involves other characters like Arthur, Lancelot, Merlin, Enide, and more. First the Queen is only represented as Arthur’s unfaithful wife, and her abduction is narrated. We have here the basis of her character. Chrétien de Troyes develops this basic character into a woman of important values about love and chivalry. -

Echoes of Legend: Magic As the Bridge Between a Pagan Past And

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 5-2018 Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur Josh Mangle Winthrop University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mangle, Josh, "Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur" (2018). Graduate Theses. 84. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/84 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECHOES OF LEGEND: MAGIC AS THE BRIDGE BETWEEN A PAGAN PAST AND A CHRISTIAN FUTURE IN SIR THOMAS MALORY’S LE MORTE DARTHUR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of the College of Arts and Sciences In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts In English Winthrop University May 2018 By Josh Mangle ii Abstract Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur is a text that tells the story of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Malory wrote this tale by synthesizing various Arthurian sources, the most important of which being the Post-Vulgate cycle. Malory’s work features a division between the Christian realm of Camelot and the pagan forces trying to destroy it. -

An Ethnically Cleansed Faery? Tolkien and the Matter of Britain

An Ethnically Cleased Faery? An Ethnically Cleansed Faery? Tolkien and the Matter of Britain David Doughan Aii earlier version of this article was presented at the Tolkien Society Seminar in Bournemouth, 1994. 1 was from early days grieved by the Logres” (p. 369), by which he means a poverty of my own beloved country: it had specifically Arthurian presence. It is most no stories of its own (bound up with its interesting that Lewis, following the confused or tongue and soil), not of the quality 1 sought, uninformed example of Williams, uses the name and found (as an ingredient) in legends of “Logres”, which is in fact derived from Lloegr other lands ... nothing English, save (the Welsh word for England), to identify the impoverished chap-book stuff. Of course Arthurian tradition, i.e. the Matter of Britain! No there was and is all the Arthurian world, but wonder Britain keeps on rebelling against powerful as it is, it is imperfectly Logres. And despite Tolkien's efforts, he could naturalised, associated with the soil of not stop Prydain bursting into Lloegr and Britain, but not with English; and does not transforming it. replace what I felt to be missing. (Tolkien In The Book of Lost Tales (Tolkien, 1983), 1981, Letters, p. 144) Ottor W<efre, father of Hengest and Horsa, also To a large extent, Tolkien is right. The known as Eriol, comes from Heligoland to the mediaeval jongleurs, minstrels, troubadours, island called in Qenya in Tol Eressea (the lonely trouvères and conteurs could use, for their isle), or in Gnomish Dor Faidwcn (the land of stories, their gests and their lays, the Matter of release, or the fairy land), or in Old English se Rome (which had nothing to do with Rome, and uncujm holm (the unknown island). -

Actions Héroïques

Shadows over Camelot FAQ 1.0 Oct 12, 2005 The following FAQ lists some of the most frequently asked questions surrounding the Shadows over Camelot boardgame. This list will be revised and expanded by the Authors as required. Many of the points below are simply a repetition of some easily overlooked rules, while a few others offer clarifications or provide a definitive interpretation of rules. For your convenience, they have been regrouped and classified by general subject. I. The Heroic Actions A Knight may only do multiple actions during his turn if each of these actions is of a DIFFERENT nature. For memory, the 5 possible action types are: A. Moving to a new place B. Performing a Quest-specific action C. Playing a Special White card D. Healing yourself E. Accusing another Knight of being the Traitor. Example: It is Sir Tristan's turn, and he is on the Black Knight Quest. He plays the last Fight card required to end the Quest (action of type B). He thus automatically returns to Camelot at no cost. This move does not count as an action, since it was automatically triggered by the completion of the Quest. Once in Camelot, Tristan will neither be able to draw White cards nor fight the Siege Engines, if he chooses to perform a second Heroic Action. This is because this would be a second Quest-specific (Action of type B) action! On the other hand, he could immediately move to another new Quest (because he hasn't chosen a Move action (Action of type A.) yet. -

THE NAMES of OLD-ENGLISH MINT-TOWNS: THEIR ORIGINAL FORM and MEANING and THEIR EPIGRAPHICAL CORRUPTION—Continued

THE NAMES OF OLD-ENGLISH MINT-TOWNS: THEIR ORIGINAL FORM AND MEANING AND THEIR EPIGRAPHICAL CORRUPTION—Continued. BY ALFRED ANSCOMBE, F.R.HIST.SOC. II. THE NAMES OF OLD-ENGLISH MINT-TOWNS WHICH OCCUR IN THE SAXON CHRONICLES. CHAPTER II (L—Z). 45. Leicester. of Ligera ceastre " 917, K. The peace is broken by Danes — -ere- D ; -ra- B ; -re- C. " set Ligra ceastre' 918, C. The Lady Ethelfleda gets peaceful possession of the burg Legra-, B ; Ligran-, D. " Ligora ceaster " 942, ft. One of the Five Burghs of the Danes. -era-, B, C ; -ere- D. " jet Legra ceastre 943, D. Siege laid by King Edmund. The syllables -ora, -era, are worn fragments of wara, the gen. pi. of warn. This word has been explained already; v. 26, Canterbury, Part II, vol. ix, pp. 107, 108. Ligora.-then equals Ligwara-ceaster, i.e., the city of the Lig-waru. For the falling out of w Worcester (<Wiog- ora-ceaster) Canterbury (< Cant wara burh) and Nidarium (gen. pi. ; < Niduarium) may be compared. The distinction between the Old-English forms of Leicester and Chester lies in the presence or absence of the letter r. The meaning of #Ligwaru, the Ligfolk, has not yet been deter- mined owing- to the fact that Old-English scholars have not consulted o o their Welsh fellow-workers. In old romance the name for the central Naes of Old-English Mint-towns in the Saxon Chronicles. parts of England south of the Humber and Mersey is " Logres." This is Logre with the addition of the Norman-French 5 of the nominative case. -

Excalibur Avalon Restaurant Menu

Excalibur Avalon Restaurant Menu Transforming medieval recipes into products to tickle twenty-first century taste buds is an exciting challenge, and this is where the fusion between past and present really happens. The Avalon Restaurant combines modern technology with medieval flavours to create a surprisingly happy pairing. Medieval food was seasonal, sustainable, and often dairy-free. What’s not to love! Recreating medieval dishes is an adventure. Medieval cookbooks only detail the food of the elite, and it’s unlikely that any were written by the cooks themselves! Like incomplete puzzles, the recipes rarely mention quantities, or temperatures, and give few instructions. We have sensitively reconstructed, with a dose of creative license, truly unique and tantalizing dishes to transport your culinary senses on a true journey of discovery. NOTES Kindly inform the hotel staff of any allergies prior to placing an order (All food may contain traces of nuts) Consuming raw or undercooked meat, seafood or egg products can increase your risk of food borne illness. Please allow 35 minutes for your order, 45 minutes if “Well Done” to be served, tables with large number of guests please allow a longer waiting time A 10% Service charge will be added to tables of 10 and more. PLEASE NOTE NO PERSON IS ALLOWED TO PLAY ON THE FOUNTAIN OR IN THE WATER FOR THEIR OWN SAFETY BREAKFAST SERVED FROM 08H00 – 11H00 All our Breakfast items are served with a glass of fruit juice or a cup of coffee/tea. Squires Breakfast R49 Two eggs (fried, poached, boiled or scrambled), grilled bacon, grilled tomato and one slice of white or brown toast. -

Monty Python's SPAMALOT

Monty Python’s Spamalot CHARACTERS Please note that the ages listed just serve as a guide. All roles are available and casting is open, and newcomers are welcome and encouraged. Also, character doublings are only suggested here and may be changed based on audition results and production needs. KING ARTHUR (Baritone, Late 30s-60s) – The King of England, who sets out on a quest to form the Knights of the Round Table and find the Holy Grail. Great humor. Good singer. THE LADY OF THE LAKE (Alto with large range, 20s-40s) – A Diva. Strong, beautiful, possesses mystical powers. The leading lady of the show. Great singing voice is essential, as she must be able to sing effortlessly in many styles and vocal registers. Sings everything from opera to pop to scatting. Gets angry easily. SIR ROBIN (Tenor/Baritone, 30s-40s) – A Knight of the Round Table. Ironically called "Sir Robin the Brave," though he couldn't be more cowardly. Joins the Knights for the singing and dancing. Also plays GUARD 1 and BROTHER MAYNARD, a long-winded monk. A good mover. SIR LANCELOT (Tenor/Baritone, 30s-40s) – A Knight of the Round Table. He is fearless to a bloody fault but through a twist of fate discovers his "softer side." This actor MUST be great with character voices and accents, as he also plays THE FRENCH TAUNTER, an arrogant, condescending, over-the-top Frenchman; the KNIGHT OF NI, an absurd, cartoonish leader of a peculiar group of Knights; and TIM THE ENCHANTER, a ghostly being with a Scottish accent. -

The Height of Its Womanhood': Women and Genderin Welsh Nationalism, 1847-1945

'The height of its womanhood': Women and genderin Welsh nationalism, 1847-1945 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kreider, Jodie Alysa Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 04:59:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280621 'THE HEIGHT OF ITS WOMANHOOD': WOMEN AND GENDER IN WELSH NATIONALISM, 1847-1945 by Jodie Alysa Kreider Copyright © Jodie Alysa Kreider 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partia' Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2004 UMI Number: 3145085 Copyright 2004 by Kreider, Jodie Alysa All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3145085 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

The Case of Michael Du Val's the Spanish English Rose

SEDERI Yearbook ISSN: 1135-7789 [email protected] Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies España Álvarez Recio, Leticia Pro-match literature and royal supremacy: The case of Michael Du Val’s The Spanish English Rose (1622) SEDERI Yearbook, núm. 22, 2012, pp. 7-27 Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies Valladolid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=333528766001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Pro-match literature and royal supremacy: The case of Michael Du Val’s The Spanish English Rose (1622) Leticia Álvarez Recio Universidad de Sevilla ABSTRACT In the years 1622-1623, at the climax of the negotiations for the Spanish-Match, King James enforced censorship on any works critical of his diplomatic policy and promoted the publication of texts that sided with his views on international relations, even though such writings may have sometimes gone beyond the propagandistic aims expected by the monarch. This is the case of Michael Du Val’s The Spanish-English Rose (1622), a political tract elaborated within court circles to promote the Anglo-Spanish alliance. This article analyzes its role in producing an alternative to the religious and imperial discourse inherited from the Elizabethan age. It also considers the intertextual relations between Du Val’s tract and other contemporary works in order to determine its part within the discursive network of the Anglican faith and political absolutism. -

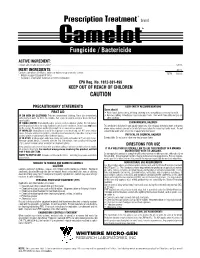

Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide

® Prescription Treatment brand Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide ACTIVE INGREDIENT: Copper salts of fatty and rosin acids† . 58.0% INERT INGREDIENTS: . 42.0% Contains petroleum distillates, xylene or xylene range aromatic solvent. TOTAL 100.0% † Metallic Copper Equivalent 5.14%) * Camelot is a registered Trademark of Griffin Corporation. EPA Reg. No. 1812-381-499 KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN CAUTION PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS USER SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS Users should: FIRST AID • Wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco or using the toilet. IF ON SKIN OR CLOTHING: Take off contaminated clothing. Rinse skin immediately • Remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on with plenty of water for 15 to 20 minutes. Call a poison control center or doctor for treat- clean clothing. ment advice. IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a poison control center or doctor. Do not induce ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. Do not give any liquid This pesticide is toxic to fish and aquatic organisms. Do not apply directly to water, or to areas to the person. Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. where surface water is present or to intertidal areas below the mean high water mark. Do not IF INHALED: Move person to fresh air. If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambu- contaminate water when disposing of equipment washwaters. lance, then give artificial respiration, preferably mouth-to-mouth, if possible. Call a poison control center or doctor for further treatment advice. PHYSICAL OR CHEMICAL HAZARDS IF IN EYES: Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15 to 20 minutes. -

The Duke: Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack

™ Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack The politics of the high courts are elegant, shadowy, and subtle. Fort Tile: Players can use the Fort Tile as shown on pages 7-8 of Not so in the outlying duchies. Rival dukes contend for unclaimed the rulebook for any game with these tiles. However, they can also lands far from the king’s reach, and possession is the law in these play with the reverse side of the Fort, Camelot. Camelot is an Ex- lands. Use your forces to adapt to your opponent’s strategies, cap- panded Play tile (see p. 6 of the rulebook) and so both players should turing enemy troops, before you lose your opportunity to seize these agree to its use before play begins. lands for your good. Randomly place Camelot in any square in one of the two middle In The Duke, players move their troops (tiles) around the board rows of the board. and flip them over after each move. Each tile’s side shows a different For the Arthur player, if one of his Arthurian Legends’ tiles is in- movement pattern. If you end your movement in a square occupied side Camelot (King Arthur, Lancelot, Guinevere, Percival, or Merlin), by an opponent’s tile, you capture that tile. Capture your opponent’s then the Camelot Tile gains Command ability in all eight squares Duke to win! surrounding Camelot. On his turn, any time those conditions are met, the player may use the Command ability of Camelot; the Troop ARTHurIan leGenDS EXPanSIon PacK RULES Tile on Camelot does not flip, but the Camelot Tile DOES flip over to Arthur, Guineviere, Merlin, Lancelot and Perceval replace the light the Fort side; as long as it’s on the Fort side, the Command ability no stained Duke, Duchess, Wizard, Champion and Assassin Tiles. -

Bristol: a City Divided? Ethnic Minority Disadvantage in Education and Employment

Intelligence for a multi-ethnic Britain January 2017 Bristol: a city divided? Ethnic Minority disadvantage in Education and Employment Summary This Briefing draws on data from the 2001 and 2011 Figure 1. Population 2001 and 2011. Censuses and workshop discussions of academic researchers, community representatives and service providers, to identify 2011 patterns and drivers of ethnic inequalities in Bristol, and potential solutions. The main findings are: 2001 • Ethnic minorities in Bristol experience greater disadvantage than in England and Wales as a whole in 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% education and employment and this is particularly so for White British Indian Black African Black African people. White Irish Pakistani Black Caribbean Gypsy or Irish Traveller Bangladeshi Other Black • There was a decrease in the proportion of young people White other Chinese Arab with no educational qualifications in Bristol, for all ethnic Mixed Other Asian Any other groups, between 2001 and 2011. • Black African young people are persistently disadvantaged Source: Census 2001 & 2011 in education compared to their White peers. • Addressing educational inequalities requires attention Ethnic minorities in Bristol experience greater disadvantage to: the unrepresentativeness of the curriculum, lack of than the national average in education and employment, diversity in teaching staff and school leadership and poor as shown in Tables 1 and 2. In Education, ethnic minorities engagement with parents. in England and Wales on average have higher proportions • Bristol was ranked 55th for employment inequality with qualifications than White British people but this is between White British and ethnic minorities. not the case in Bristol, and inequality for the Black African • People from Black African (19%), Other (15%) and Black Caribbean (12.7%) groups had persistently high levels of Measuring Local Ethnic Inequalities unemployment.