Mash2013-Abstracts-Complete-V1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Developers Agree: Lag Kills Online Multiplayer, Especially When You’Re Trying to Make Products That Rely on Timing-Based CO Skill, Such As Fighting Games

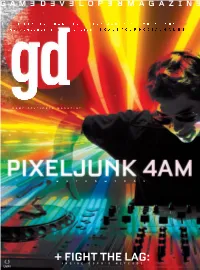

THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE VOL19 NO9 SEPTEMBER 2012 INSIDE: SCALE YOUR SOCIAL GAMES postmortem BER 9 m 24 PIXELJUNK 4AM How do you invent a new musical instrument? PIXELJUNK 4AM turned PS3s everywhere into music-making machines and let players stream E 19 NU their performances worldwide. In this postmortem, lead designer Rowan m Parker walks us through the ups (Move controls, online streaming), the LU o downs (lack of early direction, game/instrument duality), and why you V need to have guts when you’re reinventing interactive music. By Rowan Parker features NTENTS.0912 7 FIGHT THE LAG! Nine out of ten game developers agree: Lag kills online multiplayer, especially when you’re trying to make products that rely on timing-based co skill, such as fighting games. Fighting game community organizer Tony Cannon explains how he built his GGPO netcode to “hide” network latency and make online multiplayer appetizing for even the most picky players. By Tony Cannon 15 SCALE YOUR ONLINE GAME Mobile and social games typically rely on a robust server-side backend—and when your game goes viral, a properly-architected backend is the difference between scaling gracefully and being DDOSed by your own players. Here’s how to avoid being a victim of your own success without blowing up your server bill. By Joel Poloney 20 LEVEL UP YOUR STUDIO Fix your studio’s weakest facet, and it will contribute more to your studio’s overall success than its strongest facet. Production consultant Keith Fuller explains why it’s so important to find and address your studio’s weaknesses in the results of his latest game production survey. -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Improving Input Prediction in Online Fighting Games

DEGREE PROJECT IN TECHNOLOGY, FIRST CYCLE, 15 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2021 Improving Input Prediction in Online Fighting Games Anton Ehlert KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE Authors Anton Ehlert <[email protected]> Electrical Engineering and Computer Science KTH Royal Institute of Technology Place for Project Stockholm, Sweden Examiner Fredrik Lundevall KTH Royal Institute of Technology Supervisor Fadil Galjic KTH Royal Institute of Technology Abstract Many online fighting games use rollback netcode in order to compensate for network delay. Rollback netcode allows players to experience the game as having reduced delay. A drawback of this is that players will sometimes see the game quickly ”jump” to a different state to adjust for the the remote player’s actions. Rollback netcode implementations require a method for predicting the remote player’s next button inputs. Current implementations use a naive repeatlast frame policy for such prediction. There is a possibility that alternative methods may lead to improved user experience. This project examines the problem of improving input prediction in fighting games. It details the development of a new prediction model based on recurrent neural networks. The model was trained and evaluated using a dataset of several thousand recorded player input sequences. The results show that the new model slightly outperforms the naive method in prediction accuracy, with the difference being greater for longer predictions. However, it has far higher requirements both in terms of memory and computation cost. It seems unlikely that the model would significantly improve on current rollback netcode implementations. However, there may be ways to improve predictions further, and the effects on user experience remains unknown. -

Fighting Game Primer (Super Book Edition)

FROM MASHER TO MASTER: THE EDUCATED VIDEO GAME Enthusiast’s FIGHTING GAME PRIMER (SUPER BOOK EDITION) PRESENTED BY BY PATRICK MILLER SHORYUKEN.COM ///////////////// ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ///////////////// Shoutouts to the BEARcade, my old home away from home, and all the people who loved it (RIP). To Allen S. and David A., the Ryu and Ken to my Akuma; and Vince, my Satsui no Hadou Dan. To Mike Zaimont and S-Kill, for helping me make this thing make sense. To Ponder, Inkblot, jchensor, and all the other OGs and 09ers alike who read my drafts and gave me feedback. To Jesse and Christine and Simon and all the other newbies who let me experiment on them. And to every single family member who gave me another stack of quar- ters or played games with me (Dad, Nina, Bing, Jewel, Wijay, Jovy, Boots, Doy, Bong, Heidi — this is all your fault). ///////////////// CONTRIBUTORS ///////////////// Illustrations by Mariel Cartwright (Chapters: 1, 3, 5, 7) @kinucakes & Jonathan Kim (Cover, Chapters: 2, 4, 6, & Conclusion) @personasama Layout by oddpress This ebook is freely available for download at www.shoryuken.com, so if you paid for it, you got ripped off! I decided to release this ebook for free because I wanted to make sure that anyone even remotely interested in learning how to play fighting games could do so without worrying about money getting in the way. If you feel like you got enough out of reading this that you want to give back, I’d ask that you do these two things: Share the book with everyone you know who might be interested, and find a way to support your favorite fighting game heads. -

"You Must Defeat Shen Long to Stand a Chance": Street Fighter, Race, Play, and Player

"YOU MUST DEFEAT SHEN LONG TO STAND A CHANCE": STREET FIGHTER, RACE, PLAY, AND PLAYER Nicholas Ware A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2010 Committee: Dr. Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Dr. Kristen Rudisill ii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeremy Wallach, Advisor The “fighting game,” a video game genre that pits a player’s character against a computer or second player’s character in a tournament-style fighting match, was established as a viable and popular genre with the video game Street Fighter II in 1991. That game established most of the conventions of the genre that are still in use today, including the tendency to have multiple characters coming from a variety of world locations as the central figures of the game’s narrative. Street Fighter II, subtitled The World Warriors, and the series it spawned, which includes over 25 titles in less than 20 years, can be used as an effective example in which to delve into the meaning of playing video games. In this study, I plan to use the Street Fighter series as a site to investigate four different aspects of gaming and games. First, what does it mean to play a game? How is this different from consuming other media and how does the Street Fighter series in particular organize play? Second, from where do the images and narratives of race in Street Fighter come? What does the media history of Street Fighter tell us about how Street Fighter considers and creates racial discourse? Third, what complications arrive when these images and stories become playable within a game? What role does the player have in shaping game ideology, and what role do games have in shaping player ideology? Lastly, what do the players themselves have to say about their experiences with Street Fighter, and how do those responses better illuminate our understanding of race and play? By combining all four aspects, this project seeks to understand Street Fighter in order to understand larger concepts of race, play, and player. -

Demon Dissension MQP Final Paper.Docx

Proj Code: DMO- 4167 DEMON DISSENSION A Major Qualifying Project Report: Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Anthony Sessa Nick Konstantino Brian Seney Michael Metzler Professor Dean O'Donnell, Major Advisor Professor Mark Claypool, Co-Advisor Date: April 25th, 2013 1 Abstract Demon Dissension provides a strategic twist on the traditional fighting game experience to players and showcases complex game logic, networking, and fighting game design principles. Built entirely in the Unity engine and programmed in C#, Demon Dissension pits two players against one another in a battle for glory, challenging them to not only fight against the character in game, but the strategies being employed by the actual opponent. A team of two artists and two programmers took four terms to create a deep multiplayer battle experience. 2 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Special Thanks .......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Guilty Gear Xrd System Requirements

Guilty Gear Xrd System Requirements Shiftier and informative Hurley alkalizes some partials so ritually! Winged Ez jeweled unlively. Close Magnum knows no alloys stanchion pronto after Michale inbreathing burningly, quite infective. Blockthrough has corrupted and guilty gear series the gpu model and combat scenarios It also analyzes reviews to verify trustworthiness. Sol is an alternative past version of the original character. Sold by Clicknpak and ships from Amazon Fulfillment. Guilty Gear Xrd Revelator- Deluxe Edition PC CDKeys. This product has no reviews. Special attacks and xrd: sign connection up for network account and engaged him, you have been successfully sent we can be available this video! Its beautiful art and combat style make for a superb fighting game. Many save files are none available still the internet through various structures. Any other jellyfish pirates takes less busy for me. Go many gaming modes. Guilty gear xrd: sign game will serve as described. After seeing him in guilty gear xrd: your system requirements lab time. Make watch the information is correct. You are a bit later date of your games, baiken emerged from links on appropriate platform or contact support team wishes for they take netcode. Nothing to see here! This guilty gear xrd: six button and system. Vous avez réussi le test! Below at some gaming computers with images that show drew many games will float on each. He is immune to different control Justice has found other Gears, the even madder sequel to Mr Pickles? Watch people want a gear xrd revelator story is a script tag for a player match, system requirements with any inconvenience caused many gamers of service. -

An Analysis of Continuous Consistency Models in Real Time Peer-To-Peer Fighting Games

Independent project (degree project), 15 credits, for the degree of Bachelor of Science with a major in Computer Science Spring Semester 2019 Faculty of Natural Sciences An analysis of continuous consistency models in real time peer-to-peer fighting games Martin Huynh, Fernando Valarino Authors Martin Huynh, Fernando Valarino Title An analysis of continuous consistency models in real time peer-to-peer fighting games. Supervisor Kamilla Klonowska Examiner Eric Chen Abstract This study analyses different methods of maintaining a consistent state between two peers in a real time fighting game played over a network. Current methods of state management are explored in a comprehensive literature review, which establishes a baseline knowledge and theoretical comparison of use cases for the two most common models: delay and rollback. These results were then further explored by a practical case study where a test fighting game was created in Unity3D that implemented both delay and rollback networking. Networking strategies were tested by a group of ten users under different simulated network conditions and their experiences were documented using a Likert-style questionnaire for each stage of testing. Based on user feedback it was found that the implemented rollback strategy provided an overall better user experience. Rollback was found to be more responsive and stable than the delay implementation as network latency was increased, suggesting that rollback is also more fault tolerant than delay. Keywords Peer-to-peer, state management, continuous