Women's Legal Landmarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ship 2014/2015

A more unusual focus in your magazine this College St Anne’s year: architecture and the engineering skills that make our modern buildings possible. The start of our new building made this an obvious choice, but from there we go on to look at engineering as a career and at the failures and University of Oxford follies of megaprojects around the world. Not that we are without the usual literary content, this year even wider in range and more honoured by awards than ever. And, as always, thanks to the generosity and skills of our contributors, St Anne’s College Record a variety of content and experience that we hope will entertain, inspire – and at times maybe shock you. My thanks to the many people who made this issue possible, in particular Kate Davy, without whose support it could not happen. Hope you enjoy it – and keep the ideas coming; we need 2014 – 2015 them! - Number 104 - The Ship Annual Publication of the St Anne’s Society 2014 – 2015 The Ship St Anne’s College 2014 – 2015 Woodstock Road Oxford OX2 6HS UK The Ship +44 (0) 1865 274800 [email protected] 2014 – 2015 www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk St Anne’s College St Anne’s College Alumnae log-in area Development Office Contacts: Lost alumnae Register for the log-in area of our website Over the years the College has lost touch (available at https://www.alumniweb.ox.ac. Jules Foster with some of our alumnae. We would very uk/st-annes) to connect with other alumnae, Director of Development much like to re-establish contact, and receive our latest news and updates, and +44 (0)1865 284536 invite them back to our events and send send in your latest news and updates. -

Item Captions Teachers Guide

SUFFRAGE IN A BOX: ITEM CAPTIONS TEACHERS GUIDE 1 1 The Polling Station. (Publisher: Suffrage Atelier). 1 Suffrage campaigners were experts in creating powerful propaganda images which expressed their sense of injustice. This image shows the whole range of women being kept out of the polling station by the law and authority represented by the policeman. These include musicians, clerical workers, mothers, university graduates, nurses, mayors, and artists. The men include gentlemen, manual workers, and agricultural labourers. This hints at the class hierarchies and tensions which were so important in British society at this time, and which also influenced the suffrage movement. All the women are represented as gracious and dignified, in contrast to the men, who are slouching and casual. This image was produced by the Suffrage Atelier, which brought together artists to create pictures which could be quickly and easily reproduced. ©Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection; Postcards 12 (385) Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford John Johnson Collection; Postcards 12 (385) 2 The late Miss E.W. Davison (1913). Emily Wilding Davison is best known as the suffragette who 2 died after being trampled by the King’s horse on Derby Day, but as this photo shows, there was much more to her story. She studied at Royal Holloway College in London and St Hugh’s College Oxford, but left her job as a teacher to become a full- time suffragette. She was one of the most committed militants, who famously hid in a cupboard in the House of Commons on census night, 1911, so that she could give this as her address, and was the first woman to begin setting fire to post boxes. -

The Ohio State University

MAKING COMMON CAUSE?: WESTERN AND MIDDLE EASTERN FEMINISTS IN THE INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MOVEMENT, 1911-1948 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charlotte E. Weber, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Leila J. Rupp, Adviser Professor Susan M. Hartmann _________________________ Adviser Professor Ellen Fleischmann Department of History ABSTRACT This dissertation exposes important junctures between feminism, imperialism, and orientalism by investigating the encounter between Western and Middle Eastern feminists in the first-wave international women’s movement. I focus primarily on the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship, and to a lesser extent, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. By examining the interaction and exchanges among Western and Middle Eastern women (at conferences and through international visits, newsletters and other correspondence), as well as their representations of “East” and “West,” this study reveals the conditions of and constraints on the potential for feminist solidarity across national, cultural, and religious boundaries. In addition to challenging the notion that feminism in the Middle East was “imposed” from outside, it also complicates conventional wisdom about the failure of the first-wave international women’s movement to accommodate difference. Influenced by growing ethos of cultural internationalism -

Chrystal Macmillan from Edinburgh Woman to Global Citizen

Chrystal Macmillan From Edinburgh Woman to Global Citizen di Helen Kay * Abstract : What inspired a rich well-educated Edinburgh woman to become a suffragist and peace activist? This paper explores the connection between feminism and pacifism through the private and published writings of Chrystal Macmillan during the first half of the 20 th century. Throughout her life, Chrystal Macmillan was conscious of a necessary connection between the gendered nature of the struggle for full citizenship and women’s work for the peaceful resolution of international disputes. In 1915, during World War One, she joined a small group of women to organise an International Congress of Women at The Hague to talk about the sufferings caused by war, to analyse the causes of war and to suggest how war could be avoided in future. Drawing on the archives of women’s international organisations, the article assesses the implications and relevance of her work for women today. Do we know what inspired a rich well-educated Edinburgh woman to become a suffragist and peace activist in the early part of the 20 th century? Miss Chrystal Macmillan was a passionate campaigner for women’s suffrage, initially in her native land of Scotland but gradually her work reached out to women at European and international levels. She wrote, she campaigned, she took part in public debates, she lobbied, she organised conferences in Great Britain and in Europe: in all, she spent her life working for political and economic liberty for women. In all her work and writing, she was opposed to the use of force and was committed, almost to the point of obsession, to pursuing the legal means to achieve political ends. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 Marie Corelli, or Mary Mackay (1855–1924) was a successful romantic novelist. The quotation is from her pamphlet, Woman or – Suffragette? A Question of National Choice (London: C. Arthur Pearson, 1907). 2 Sally Ledger and Roger Luckhurst, eds, The Fin de Siècle: A Reader in Cultural History c.1880–1900 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. xii. 3 A central text is Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer, Leviathan and the Air- pump: Hobbes, Boyle and the Experimental Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985). 4 Otto Mayr, ‘The science-technology relationship’, in Science in Context: Readings in the Sociology of Science, ed. by Barry Barnes and David Edge (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1982), pp. 155–163. 5 Nature, November 8 1900, News, p. 28. 6 For example Alison Winter, ‘A calculus of suffering: Ada Lovelace and the bodily constraints on women’s knowledge in early Victorian England’, in Science Incarnate: Historical Embodiments of Natural Knowledge, ed. by Christopher Lawrence and Steven Shapin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), pp. 202–239 and Margaret Wertheim, Pythagoras’ Trousers: God, Physics and the Gender Wars (London: Fourth Estate, 1997). 7 Carl B. Boyer, A History of Mathematics (New York: Wiley, 1968), pp. 649–650. 8 For the social construction of mathematics see David Bloor, ‘Formal and informal thought’, in Science in Context: Readings in the Sociology of Science, ed. by Barry Barnes and David Edge (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1982), pp. 117–124; Math Worlds: Philosophical and Social Studies of Mathematics and Mathematics Education, ed. by Sal Restivo, Jean Paul Bendegem and Roland Fisher (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993). -

Cat 178 Email

WOMAN AND HER SPHERE Catalogue 176 Elizabeth Crawford 5 OWEN’S ROW LONDON ECIV 4NP TEL 020 7278 9479 Email [email protected] Visit my website: womanandhersphere.com Prices are net, postage is extra at cost. Orders will be sent at the cheapest rate, consistent with safety, unless I am instructed otherwise. Payment is due immediately on receipt of my invoice. In some cases orders will only be sent against a proforma invoice. If paying in a currency other than sterling, please add the equivalent of £9.00 to cover bank conversion charges. This is the amount my bank charges. Or you may pay me at www.Paypal.com, using my email address as the payee account If the book you order is already sold, I will, if you wish, attempt to find a replacement copy. I would be pleased to receive your ‘wants’ lists. Orders may be sent by telephone, post, or email. Image taken from item 346 The Women’s Suffrage Movement 1866-1928: A reference guide Elizabeth Crawford ‘It is no exaggeration to describe Elizabeth Crawford’s Guide as a landmark in the history of the women’s movement...’ History Today Routledge, 2000 785pp paperback £65 The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain and Ireland: a regional survey Elizabeth Crawford ‘Crawford provides meticulous accounts of the activists, petitions, organisations, and major events pertaining to each county.’ Victorian Studies Routledge, 2008 320pp paperback £26 Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle ‘Crawford’s scholarship is admirable and Enterprising Women offers increasingly compelling reading’ Journal of William Morris Studies Francis Boutle, 2002 338pp 75 illus paperback £25 Non-fiction 1. -

Directory 2016/17 the Royal Society of Edinburgh

cover_cover2013 19/04/2016 16:52 Page 1 The Royal Society of Edinburgh T h e R o Directory 2016/17 y a l S o c i e t y o f E d i n b u r g h D i r e c t o r y 2 0 1 6 / 1 7 Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling Limited, Dorchester, DT1 1HD ISSN 1476-4334 THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH DIRECTORY 2016/2017 PUBLISHED BY THE RSE SCOTLAND FOUNDATION ISSN 1476-4334 The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street Edinburgh EH2 2PQ Telephone : 0131 240 5000 Fax : 0131 240 5024 email: [email protected] web: www.royalsoced.org.uk Scottish Charity No. SC 000470 Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling Limited CONTENTS THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH .....................................................3 COUNCIL OF THE SOCIETY ..............................................................5 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE ..................................................................6 THE RSE SCOTLAND FOUNDATION ..................................................7 THE RSE SCOTLAND SCIO ................................................................8 RSE STAFF ........................................................................................9 LAWS OF THE SOCIETY (revised October 2014) ..............................13 STANDING COMMITTEES OF COUNCIL ..........................................27 SECTIONAL COMMITTEES AND THE ELECTORAL PROCESS ............37 DEATHS REPORTED 26 March 2014 - 06 April 2016 .....................................................43 FELLOWS ELECTED March 2015 ...................................................................................45 -

Remembering Chrystal Macmillan: Women's Equality and Nationality in International Law

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 22 Issue 4 2001 Remembering Chrystal MacMillan: Women's Equality and Nationality in International Law Karen Knop University of Toronto Christine Chinkin London School of Economics and Political Science Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Immigration Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Karen Knop & Christine Chinkin, Remembering Chrystal MacMillan: Women's Equality and Nationality in International Law, 22 MICH. J. INT'L L. 523 (2001). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol22/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMEMBERING CHRYSTAL MACMILLAN: WOMEN'S EQUALITY AND NATIONALITY IN INTERNATIONAL LAW Karen Knop* Christine Chinkin** I. CONTEMPORARY RELEVANCE ....................................................... 532 II. NATIONALITY UNDER INTERNATIONAL AND DOMESTIC LAW ..... 536 A. The Concept of Nationality.................................................. 536 B. Bases for Nationality ........................................................... 542 III. ANALYZING WOMEN'S EQUALITY IN NATIONALITY -

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Special Collections Libraries University of Georgia Index 1. Legal Treatises. Ca. 1575-2007 (29). Age of Enlightenment. An Awareness of Social Justice for Women. Women in History and Law. 2. American First Wave. 1849-1949 (35). American Pamphlets timeline with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. American Pamphlets: 1849-1970. 3. American Pamphlets (44) American pamphlets time-line with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. 4. American Pamphlets. 1849-1970 (47). 5. U.K. First Wave: 1871-1908 (18). 6. U.K. Pamphlets. 1852-1921 (15). 7. Letter, autographs, notes, etc. U.S. & U.K. 1807-1985 (116). 8. Individual Collections: 1873-1980 (165). Myra Bradwell - Susan B. Anthony Correspondence. The Emily Duval Collection - British Suffragette. Ablerta Martie Hill Collection - American Suffragist. N.O.W. Collection - West Point ‘8’. Photographs. Lucy Hargrett Draper Personal Papers (not yet received) 9. Postcards, Woman’s Suffrage, U.S. (235). 10. Postcards, Women’s Suffrage, U.K. (92). 11. Women’s Suffrage Advocacy Campaigns (300). Leaflets. Broadsides. Extracts Fliers, handbills, handouts, circulars, etc. Off-Prints. 12. Suffrage Iconography (115). Posters. Drawings. Cartoons. Original Art. 13. Suffrage Artifacts: U.S. & U.K. (81). 14. Photographs, U.S. & U.K. Women of Achievement (83). 15. Artifacts, Political Pins, Badges, Ribbons, Lapel Pins (460). First Wave: 1840-1960. Second Wave: Feminist Movement - 1960-1990s. Third Wave: Liberation Movement - 1990-to present. 16. Ephemera, Printed material, etc (114). 17. U.S. & U.K. -

1 Primary Source Extracts Marion Reid

PRIMARY SOURCE EXTRACTS MARION REID (1815-1902) Reid published her ‘Plea for Women’ shortly after attending the World Anti- Slavery Convention in London in 1840. It was probably the first work in Britain or the USA to give priority to achieving civil and political rights for women. Mrs Hugo [Marion] Reid, A Plea for Woman: being a vindication of the importance and extent of her natural sphere of action; with remarks on recent works on the subject (Edinburgh: William Tait; London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co; Dublin: John Cumming, 1843) Chapter V. Woman’s Claim to Equal Rights “To see one half of the human race excluded by the other from all participation of government, is a political phenomenon which, according to abstract principles, it is impossible to explain” – Talleyrand ... The ground on which equality is claimed for all men is of equal force for all women; for women share the common nature of humanity, and are possessed of all those noble faculties which constitute man a responsible being, and give him a claim to be his own ruler, so far as is consistent with order, and the possession of the like degree of sovereignty over himself by every other human being. It is the possession of the noble faculties of reason and conscience which elevates man above the brutes, and invests him with this right of exercising supreme authority over himself. It is more especially the possession of an inward rule of rectitude, a law written on the heart in indelible characters, which raises him to this high dignity, and renders him an accountable being, by impressing him with the conviction that there are certain duties which he owes to his fellow-creatures. -

The Inter-American Commission of Women: a New International Venture

The Inter-American Commission of Women: A New International Venture By MUNA LEE Few international questions present such conflicting and perplexing aspects as that of the nationality of women. It is a modern question, because only within the last generation or so have women, generally speaking, begun to travel widely and carry on diverse activities in a complex and ever-changing world. Women might lose their nationality fifty years ago, as indeed they did often, without ever becoming aware of the fact. Not only were they less likely to leave their own country, but they were less likely to marry foreigners. Now they have been forced into a rude awareness of the completely chaotic conditions of existing nationality laws. A woman may find herself possessing several nationalities or none! In some countries, a married woman takes the nationality of her husband in all cases. Sometimes, she loses her nationality on marrying a foreigner, providing that her husband’s country gives her her nationality. Again, she loses it only if she goes to her husband’s country to live, and if that country gives her his nationality. In other countries, the law works both ways: a native woman who marries a foreigner takes his nationality; a foreign woman who marries a native man takes his nationality. But in still others the law works only one way. In other cases, which give rise to lamentable and even tragic situations, a woman has no nationality. An Englishwoman, for example, married to an Argentine, ceases to enjoy British nationality according to British law, but does not become Argentine by Argentine law; she is cast off by her own country and not accepted by her husband’s. -

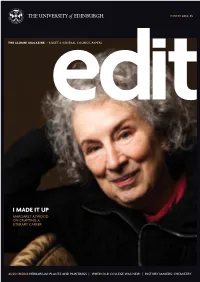

I Made It up Margaret Atwood on Crafting a Literary Career

WINTER 2014 | 15 THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE + BILLET & GENERAL COUNCIL PAPERS I MADE IT UP MARGARET ATWOOD ON CRAFTING A LITERARY CAREER ALSO INSIDE HERBARIUM: PLANTS AND PAINTINGS | WHEN OLD COLLEGE WAS NEW | HISTORY MAKERS: CHEMISTRY WINTER 2014 | 15 CONTENTS FOREWORD CONTENTS elcome to the winter edition of Edit. Edinburgh 08 16 W and Scotland have a place in the hearts of countless people throughout the world, and the leading poet and author Margaret Atwood is no exception. She Inspiration can be your legacy spoke to Edit as she received an honorary degree from the University of Edinburgh, and her interview on pages “A university and a gallery have much in common. 6-7 is a characteristic blend of humour and insight, taking in the power of access to higher education to bring 10 12 Challenging. Beautiful. Visionary. about social change, and including a mention of Irn-Bru. Designed to inspire the hearts and minds Anniversaries crop up throughout this edition of your magazine. A ceremony launching a major refurbishment of of the leaders and creators of tomorrow.” Old College also celebrated the laying of the foundation Pat Fisher, Principal Curator, stone 225 years ago. We open the cabinet doors of one of 18 Talbot Rice Gallery www.ed.ac.uk/talbot-rice the world's leading herbariums, which, jointly founded by the University in the 19th century, has been in its current home for 50 years. We also examine the University's unique relationship with China as the Confucius Institute for Scotland passes its 10th birthday. Edit itself moves with the times, and as we publish our latest printed magazine, 04 Digital Edit tu18 Wha Yo Did Next we have a new suite of digital offerings, all of which include additional multimedia content.