Designing Place Topologies of Maker Labs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workshop East

Co-Making: Research into London’s Open access Makerspaces and Shared Workshops Workshop East January 2015 Co-Making Spaces Study © Workshop East 1 Contents Executive summary 4 Introduction 8 A full report prepared for the London Legacy Development Corporation Key Definitions 9 and the Greater London Authority Methodology 10 Disciplines 12 Background 14 1: Initial findings and overview 17 Map of co-making spaces 18 Summary 38 Research 2014 Published January 2015 2: Workshop Profiles 39 Profiled organisations 40 Chart of profiled organisations 44 3: Themes & Case Studies 47 3.1: Setup & Management 51 Themes & Trends 74 by Workshop East 3.2: Supporting Enterprise & Business Growth 91 Themes & Trends 96 3.3: Community & Placemaking 103 with Themes & Trends 108 Engel Hadley Kirk & Rhianon Morgan-Hatch 4. Conclusions & Recommendations 110 4.1 Setup, management and space requirements 110 4.2 Supporting Enterprise & Business Growth 111 4.3 Community & Placemaking 113 4.4 Planning Strategy 114 4.5 Public Sector Collaboration 116 Glossary 119 Co-making spaces - data table 120 List of Supplementary Data 124 2 Co-Making Spaces Study © Workshop East Co-Making Spaces Study © Workshop East 3 Executive summary Workshop East was commissioned by the The second section profiles 22 spaces located London Legacy Development Corporation across London. It illustrates a variety of (LLDC) and the Greater London Authority operational models within the sector. This (GLA) to undertake research into ‘co-making’ section of information provides a greater level within London. of detail from a selection of representative spaces. Co-making as a sector and as a type of workplace was highlighted in the Local Gathered through visits and interviews, this Economy Study1 and the Artist’s Workspace information is presented in photographic and Study2 produced in 2014 by We Made That, chart form to invite constructive comparisons and in the 2014 GLA commissioned report between spaces. -

Land Movements in India Farmers Struggle Against Land Grab in PUNE DISTRICT

Land Movements in India an online resource for land rights activists Farmers Struggle against Land Grab in PUNE DISTRICT OCT 27 Posted by jansatyagraha In Pune district, the government has approved 54 SEZs for private sector industries such as Syntel International, Serum Institute, Mahindra Realty, Bharat Forge, City Parks, InfoTech Parks, Raheja Coroporation, Videocon and Xansa India. All SEZs are located around Pune, in areas like Pune Nashik National Highway, Pune-Bangalore National Highway, Pune Hyderabad National Highway and Pune Mumbai Highway. The MIDC has identified 7,500 hectares of agricultural land for procurement in the name of SEZ creation in Pune. Opposition to SEZs has become apparent in many areas, including Karla near Lonavala, Khed- Rajgurunagar, Wagholi at Pune-Aurangabd highway and Karegaon near the Ranjangaon MIDC. It is particularly strong in the Khed taluka district of Pune, where farmers from Gulani, Wafgaon, Wakalwadi, Warude, Gadakwadi, Chaudharwadi, Chinchbaigaon, Jaulake Budruk, Jarewadi, Kanesar, Pur, Gosasi, Nimgaon, Retwadi, Jaulake Khurd, Dhore Bhamburwadi and Pabal face loss of their only source of livelihood from the creation of the Bharat Forge SEZ. These communities, primarily Maratha, OBC and adivasi, are chiefly engaged in agricultural activities. Their major crops are potato, onion, sorghum, jowar, rice, flowers and pulses. Many village youth have also initiated small-scale businesses like poultry, milk collection and pig raring. Although these villages are near the Bhima River basin and surrounded by a small watershed, the government’s lack of investment in infrastructure has left local farmers dependent on unreliable tanker water. Instead of meeting demands for sustainable irrigation schemes to improve the conditions of local farmers, the government seeks to reduce the land of local citizens in order to create an SEZ. -

Pune (Maharashtra) Pin – 412 403

Track ID : MHCOGN26417 Shikshan Prasarak Mandal’s SHRI PADMAMANI JAIN COLLEGE OF ARTS & COMMERCE Pabal Tal-Shirur, Dist- Pune (Maharashtra) Pin – 412 403 Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune (ID/NO/PU/PN/AC/148/2000) SELF STUDY REPORT 2015 CYCLE 1 Submitted for Accreditation To NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL, BANGALURU Shri Padmamani Jain Arts & Commerce College, Pabal 1 | Page Shri Padmamani Jain Arts & Commerce College, Pabal 2 | Page Shri Padmamani Jain Arts & Commerce College, Pabal 3 | Page CONTENT Sr. No. Details Page No. 1. Preface 5 2. NAAC Steering committee 6 3. Executive Summary & SWOC Analysis 6-13 4. Self Study Report Institutional Data A. Profile of the Institution 14-24 B. Criteria wise analytical report 25-129 1. Criterion I Curricular Aspects 25-38 2. Criterion II Teaching, Learning and Evaluation 39-58 3. Criterion III Research, Consultancy and Extension 59-81 4. Criterion IV Infrastructure and Learning Resources 82-94 5. Criterion V Student Support and Progression 95-106 6. Criterion VI Governance , Leadership and Management 107-120 7. Criterion VII Innovations and Best Practices 121-129 C. Inputs from the Departments Department of Marathi 130-136 Department of English 137-143 Department of Hindi 144-149 Department of Economics 150-159 Department of Political Science 160-167 Department of History 168-175 Department of Geography 176-181 Department of Commerce 182-191 5 IEQA submitted to NAAC 192-194 6 Declaration by the Head of Institution 195 7 Certificate of Compliance 196 Annexure I-VIII : 197-212 Annexure-I : Master Plan of the College 197 Annexure-II : Certificate of Recognition by Govt. -

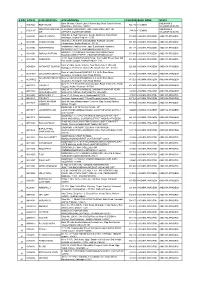

S No Atm Id Atm Location Atm Address Pincode Bank

S NO ATM ID ATM LOCATION ATM ADDRESS PINCODE BANK ZONE STATE Bank Of India, Church Lane, Phoenix Bay, Near Carmel School, ANDAMAN & ACE9022 PORT BLAIR 744 101 CHENNAI 1 Ward No.6, Port Blair - 744101 NICOBAR ISLANDS DOLYGUNJ,PORTBL ATR ROAD, PHARGOAN, DOLYGUNJ POST,OPP TO ANDAMAN & CCE8137 744103 CHENNAI 2 AIR AIRPORT, SOUTH ANDAMAN NICOBAR ISLANDS Shop No :2, Near Sai Xerox, Beside Medinova, Rajiv Road, AAX8001 ANANTHAPURA 515 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 3 Anathapur, Andhra Pradesh - 5155 Shop No 2, Ammanna Setty Building, Kothavur Junction, ACV8001 CHODAVARAM 531 036 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 4 Chodavaram, Andhra Pradesh - 53136 kiranashop 5 road junction ,opp. Sudarshana mandiram, ACV8002 NARSIPATNAM 531 116 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 5 Narsipatnam 531116 visakhapatnam (dist)-531116 DO.NO 11-183,GOPALA PATNAM, MAIN ROAD NEAR ACV8003 GOPALA PATNAM 530 047 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 6 NOOKALAMMA TEMPLE, VISAKHAPATNAM-530047 4-493, Near Bharat Petroliam Pump, Koti Reddy Street, Near Old ACY8001 CUDDAPPA 516 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 7 Bus stand Cudappa, Andhra Pradesh- 5161 Bank of India, Guntur Branch, Door No.5-25-521, Main Rd, AGN9001 KOTHAPET GUNTUR 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta, P.B.No.66, Guntur (P), Dist.Guntur, AP - 522001. 8 Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW8001 GAJUWAKA BRANCH 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 9 Gajuwaka, Anakapalle Main Road-530026 GAJUWAKA BRANCH Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW9002 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH -

MSEDCL Authority Padalkar Engineer Mail.Com Baramati Rural Circle, Urja Bhavan, II Floor, Public Information Keshav Vajanathrao Executive Sebaramati@G 1 7875768027

Baramati Zone Office,Baramati Sr. Office Name & First Appeallate Name of Assistant RTI Designation Mobile Number Email-Id No. Address officer / Public officer information officer/ Assistant Public information officer 1 Baramati Zone First Appeallate Sou. Poonam Ashish Superintending 7875768222 office officer Rokade Engineer baramati,Urjabh avan bhigwan road baramati Public information Uday Madhukar Kulkarni Executive 7875768028 officer Engineer sesatara@gmai l.com Assistant Public Dilipkumar Bajarang Deputy 7875768519 information officer Karvekar Executive Engineer Baramati Rural Circle Sr Office Name & First Appellate Name of Officer Designation in Mobile Number E-mail No Address Authority / Nodal Office Address Officer, Public Information Officer / System Administrator and Assistant Information Officer First Appellate Dattatraya Vishnu Superintending sebaramati@g 7875768111 MSEDCL Authority Padalkar Engineer mail.com Baramati Rural Circle, Urja Bhavan, II Floor, Public Information Keshav Vajanathrao Executive sebaramati@g 1 7875768027 Bhigwan road, Officer Kalumali Engineer mail.com Baramati, Pune- 413102 Assistant Information Dy Executive sebaramati@g Nilesh Ramling Borate 7875768081 Officer Engineer mail.com Baramati Division First Appellate Executive eebaramati@g Ganesh Manikrao Latpate 7875768005 Authority Engineer mail.com Baramati Division, Urjabhavan, I Public Information Dy Executive eebaramati@g 2 Floor, Bhigwan Savita Rahul Khatavkar 7875768096 Officer Engineer mail.com Road Baramati Tal : Baramati Dist : Pune Assistant Information -

Research Paper Commerce

Volume-4, Issue-4, April-2015 • ISSN No 2277 - 8160 Commerce Research Paper Geography Geographical Analysis of Shirurtahsil’s Literacy, Pune District, Ms Dr. Ratnaprabha Assist. Prof., C. T. Bora College, Shirur, Dist. Pune Santosh Jadhav ABSTRACT Literacy is one of the demographic characteristics which determines the rate of fertility, size of family, attitude about the female child, level of human resource development, socio-economic condition etc. It is the one of the determinants of eradicating poverty reduction, achieving gender equality and ensuring sustainable development. By taking into consideration the importance of literacy and its characteristics, an attempt has been made to analyze the circle-wise effective literacy,sex-wise literacy and literacy pattern in Shirur Tahsil of Pune District.The circle has been taken as a unit for analysis.For the detail analysis of literacy, 117 villages and 6 circles of this tahsil have been studiedby applying the 1991, 2001 and 2011census data from Town and Village Directory of Pune District. MS-Excel was applied to process and represent the data. ArcGIS was employed to prepare the base map and thematic maps of the study area. The study has observed that in Shirurtahsil, the effective literacy was recorded only 68.15 percent in 1991and it reached upto 82.37 percent in 2011. It showed 26 percent remarkable positive growth during the last two decades due to the development of educational facilities, transportation, agricultural and economic development etc. KEYWORDS : Literacy, literacy pattern, Effective Literacy and Sex-wise literacy. Introduction: six circles, namely Pabal, Shirur, Takali-Haji, TalegaonDhamdhere, Nha- Any person above the age of seven years, who can read and write in vara and Vadgaon-Rasai and covering 117 villages. -

Growth Sectors and SME Workspace Study

Tower Hamlets Growth Sectors and SME Workspace Study A Final Report by Regeneris Consulting, We Made That, AspinallVerdi and the Business Centre Specialist London Borough of Tower Hamlets Tower Hamlets Growth Sectors and SME Workspace Study April 2016 Regeneris Consulting Ltd www.regeneris.co.uk Tower Hamlets Growth Sectors and SME Workspace Study Contents Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Study Background and Focus 2 3. Economy and Growth Sectors 9 4. Workspace Supply and Demand 42 5. Economic and Workspace Trajectory 84 6. Moving Forward: Maintaining and Enhancing Workspace Supply 97 All Photography Courtesy of We Made That Tower Hamlets Growth Sectors and SME Workspace Study 1. Introduction Report Contents 1.6 The report is presented in the following chapters: 1.1 Regeneris Consulting, We Made That, AspinallVerdi and the Business Chapter 2: Study Background and Focus Centre Specialist were commissioned to undertake a mapping of Tower Hamlets’ small business and enterprise economy, with a Chapter 2: Economy and Growth Sectors specific focus on economic growth sectors and on demand for and Chapter 3: Workspace Supply and Demand supply of SME workspace. Chapter 4: Economic Trajectory Work Undertaken Chapter 5: Summary and Recommendations. 1.2 The research has comprised a mix of both secondary and primary research. 1.3 To understand the characteristics and trajectory of the Tower Hamlets economy, we have drawn on a range of statistical sources, including the Inter-Departmental Business Register, UK Business Count, ONS Business Demography, Business Register and Employment Survey, the Annual Population Survey and the ONS Census. 1.4 Our mapping of workspace supply in the Borough draws on a mix of desk based research, observational research / site visits and consultation with workspace providers. -

Efficacy of B12 Fortified Nutrient Bar and Yogurt in Improving Plasma B12 Concentrations

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.01.21249112; this version posted January 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Efficacy of B12 fortified nutrient bar and yogurt in improving plasma B12 concentrations – results from two double blind randomised placebo controlled trials Chittaranjan Yajnik1*, Sonal Kasture1, Vaishali Kantikar1, Himangi Lubree1, Dattatray Bhat1, Deepa Raut1, Nilam Memane1, Aboli Bhalerao1, Rasika Ladkat1, Pallavi Yajnik1, Sudhir Tomar2, Tejas Limaye1, Sanat Phatak1 Affiliations: 1. King Edward Memorial Hospital Research Center, Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2. ICAR-National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, Haryana, India. *Corresponding Author: Prof. Chittaranjan Yajnik, Diabetes Unit, King Edward Memorial Hospital Research Center, Sardar Moodiar Road, Rasta Peth, Pune – 411011. Maharashtra, India. [email protected] NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.01.21249112; this version posted January 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Background: Dietary vitamin B12 (B12) deficiency is common in Indians. It may affect hematologic and neurocognitive systems and maternal deficiency predisposes offspring to neural tube defects and non-communicable disease. Long-term tablet supplementation is not sustainable. -

Annual Report Annual Report

Annual Report 2011-12 Vigyan Ashram At.Post.Pabal Dist.Pune 412403 (A center of Indian Institute Of Education) 128/2, J.P Naik Path, Karve Road, Kothrud Pune 411038, Ph : 020-25424580 www.vigyanashram.com 1 Vigyan Ashram Annual Report 2011-12 Vigyan Ashram Annual Report 20112011----12121212 Financial year 2011-12 is marked with many landmarks for Vigyan Ashram. Most importantly Vigyan Ashram got new workshop facility with the financial support of M/S GKN Plc. and up gradation of food lab with the support of M/S Praj foundation. Important achievements and highlights of different projects of Vigyan Ashram are presented here. Vigyan Ashram is working on the philosophy of ‘Rural Development through Education System (RDES)’. Fig. 1 shows the model of RDES program. To achieve objective of rural development, VA has program, as shown in the fig. 2. Figure 1: RDES philosophy Figure 2: RDES Program 2 Vigyan Ashram Annual Report 2011-12 Following are the main program of Vigyan Ashram and major financial partners in the project (Table1). VIGYAN ASHRAM’S PROGRAM Technology Non formal Education Replication Program Infrastructural Development (DBRT & short term (Introduction to Basic Development at Pabal courses Program at Technology (IBT)) center Pabal) Program Supported by Dept of science and Asha for Education, E- Asha for education, GKN Sinter Metal, M/S Technology, INDUSA Boss, Honeywell, Lend-a-hand-India, Praj foundation, individual donor Suzlon foundation, Govt of Maharashtra, E- Hemendra Kothari BOSS (Mr.Meghaji) foundation, Govt of Chattisgarh, AID, We want to take this opportunity to thanks our donors, parents, students, villagers in Pabal and community for their continuous support and faith in Vigyan Ashram’s team. -

Vigyan Ashram Status Report

Vigyan Ashram Status Report Volume 38 Issue 08 August 2020 In this issue # Vigyan Ashram in Action # Under Lockdown • Independence Day & Ganesha Festival Celebration • Praj Foundation’s support to Rural Entrepreneurship Program • Fab School @ Mukhai School • DIC : Technology development updates • DBRT and IBT : Learn ‘Virtually’ and ‘Practice’ locally A] Independence Day & Ganesh festival celebration: 15 August Independence Day was celebrated with all Josh of celebration. Though we are missing students on campus due to pandemic. Participation by all Staff and DIC fellows made it a memorable day. There were cultural programs and sports activities. We had sport competition of relay race and underarm cricket matches. Cycle racing, limbu-chamcha (lemon spoon), Gunny sack racing were all fun. We also celebrated Ganesh festival during 21st to 26th August. VA team prepared Ganesh idol, made a small decoration & traditional ‘prasad’ during the festival. Staff also performed Barchhi dance with traditional Dhol and Tasha. It was full of fun & stress busters for team members. B] Entrepreneurship Development Program (EDP) : During past 5 months, more than 500 + rural youth, SHG members reached us through social media campaign, webinars & online training support. Presently we are providing incubation & handholding support to selected youth. Though pandemic & economic slowdown is negatively impacting rural community, many youth are willing to stay back in their villages. We are guiding them in selecting right opportunity & prepare business plan. Vishal & Ganesh visited Ahupe village (Tal-Ambegaon) on 7th Aug to survey skill training and livelihood needs of local youth. Ahupe is very remote village located at back water of Dhimbe dam. They are many reverse migrated youth in this village. -

Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father

Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father/Husband First Name Father/Husband Middle Name Father/Husband Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio No. DP.ID-CL.ID. Account No. Invest Type Amount Transferred Proposed Date of Transfer to IEPF PAN Number Aadhar Number 74/153 GANDHI NAGAR A ARULMOZHI NA INDIA Tamil Nadu 636102 IN301774-10480786-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 160.00 15-Sep-2019 ATTUR 1/26, VALLAL SEETHAKATHI SALAI A CHELLAPPA NA KILAKARAI (PO), INDIA Tamil Nadu 623517 12010900-00960311-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 60.00 15-Sep-2019 RAMANATHAPURAM KILAKARAI OLD NO E 109 NEW NO D A IRUDAYAM NA 6 DALMIA COLONY INDIA Tamil Nadu 621651 IN301637-40636357-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 20.00 15-Sep-2019 KALAKUDI VIA LALGUDI OPP ANANDA PRINTERS I A J RAMACHANDRA JAYARAMACHAR STAGE DEVRAJ URS INDIA Karnataka 577201 IN300360-10245686-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 8.00 15-Sep-2019 ACNPR4902M NAGAR SHIMOGA NEW NO.12 3RD CROSS STREET VADIVEL NAGAR A J VIJAYAKUMAR NA INDIA Tamil Nadu 632001 12010600-01683966-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 100.00 15-Sep-2019 SANKARAN PALAYAM VELLORE THIRUMANGALAM A M NIZAR NA OZHUKUPARAKKAL P O INDIA Kerala 691533 12023900-00295421-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 20.00 15-Sep-2019 AYUR AYUR FLAT - 503 SAI DATTA A MALLIKARJUNAPPA ANAGABHUSHANAPPA TOWERS RAMNAGAR INDIA Andhra Pradesh 515001 IN302863-10200863-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 80.00 15-Sep-2019 AGYPA3274E -

Aquaponics (RAS) Trial 2.0 – Experience from Vigyan Ashram , Pabal (Pune, India)

Aquaponics (RAS) Trial 2.0 – Experience from Vigyan ashram , Pabal (Pune, India) Vigyan Ashram is working on aquaponics farming system from past 3 years. Aim is to standardize this system as per Indian agro-climatic conditions and market potentials. We conducted a fresh trial @ Vigyan ashram, Pabal, Tal- Shirur, Dist- Pune during September 2016 to May2017. This report covers details of trial with some of challenges faced during this period. Following were the tested aquaponics system components & trial details as - System components - A. Bio-Bed - Plastic paper (HDPE 250 GSM) lined bio-bed was constructed with approximate volume of 10000 lit (0.7 M depth , 2.5 width & 3.5 M length ) .Total of 5 grow beds constructed with cumulative volume of 6 M2. Elevation difference of 0.25 M was maintained in each bed so as to achieve siphon based water circulation. Beds were field with red mud bricks as growing media. Coco-pit filed grow beds were also placed in each bed as vegetable planting beds while Colocasia esculenta (Alu) , Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme (Cherry tomato) , Brassica oleracea (Cauliflower), Capsicum annuum (Chilli) and Cucumis spp. (Cucumber) during trial period. B. Fish tank – Fish tank of with approximate 10000 lit capacity constructed with HDPE plastic paper linings. A drainage line was fixed at bottom of tank for removing fish / food waste. This drainage pipe was connected to sludge tank with floating valve for maintains of water level in tank. Water from fish tank is pumped to bio-bed & taken back to fish tank by with siphon based system. C.