Rapid Remittance Assessment in Bamyan and Wardak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations No

TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY OF UNIVERSITY OF TURKU MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOS DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations Patterns Migration in Iran: Afghans No. 14 TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS FROM THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF TURKU No. 1. Jukka Käyhkö and Tim Horstkotte (Eds.): Reindeer husbandry under global change in the tundra region of Northern Fennoscandia. 2017. No. 2. Jukka Käyhkö och Tim Horstkotte (Red.): Den globala förändringens inverkan på rennäringen på norra Fennoskandiens tundra. 2017. No. 3. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (doaimm.): Boazodoallu globála rievdadusaid siste Davvi-Fennoskandia duottarguovlluin. 2017. AFGHANS IN IRAN: No. 4. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (Toim.): Globaalimuutoksen vaikutus porotalouteen Pohjois-Fennoskandian tundra-alueilla. 2017. MIGRATION PATTERNS No. 5. Jussi S. Jauhiainen (Toim.): Turvapaikka Suomesta? Vuoden 2015 turvapaikanhakijat ja turvapaikkaprosessit Suomessa. 2017. AND ASPIRATIONS No. 6. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers in Lesvos, Greece, 2016-2017. 2017 No. 7. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers and irregular migrants in Lampedusa, Italy, 2017. 2017 Nro 172 No. 8. Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Katri Gadd & Justus Jokela: Paperittomat Suomessa 2017. 2018. Salavati Sarcheshmeh & Bahram Eyvazlu Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Davood No. 9. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Davood Eyvazlu: Urbanization, Refugees and Irregular Migrants in Iran, 2017. 2018. No. 10. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Ekaterina Vorobeva: Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Jordan, 2017. 2018. (Eds.) No. 11. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Refugees and Migrants in Turkey, 2018. 2018. TURKU 2008 ΕήΟΎϬϣΕϼϳΎϤΗϭΎϫϮ̴ϟϥήϳέΩ̶ϧΎΘδϧΎϐϓϥήΟΎϬϣ ISBN No. -

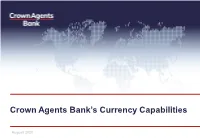

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities August 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

The Shifting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2019 The hiS fting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies Robert Righi Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the International Economics Commons Recommended Citation Righi, Robert, "The hiS fting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies" (2019). Honors Theses. 2342. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/2342 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Shifting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies by Robert Righi * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Departments of Economics and Mathematics UNION COLLEGE June 2019 Acknowledgement Thank you to both Professor Wang and Professor Motahar for their incredible support throughout the process of this work. The dedication to their students will forever be appreciated. This study would not have been at all possible without their guidance and thoughtful contributions. ii Abstract RIGHI, ROBERT J. - The Shifting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies ADVISORS - Eshragh Motahar and Jue Wang Throughout most of post World War II period, the United States dollar has been globally accepted as the dominant reserve currency. This dominance comes with “exorbitant privilege” or special benefits such as not having a balance of payments problem. Therefore, with the shifting of global geopolitical balance of power in the age of Trump, along with the recognition by the IMF of the Chinese renminbi as an international reserve currency in 2015, it is important to understand the modern influence of reserve currencies. -

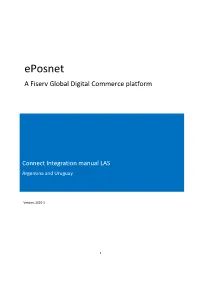

Connect Integration Manual LAS Argentina and Uruguay

ePosnet A Fiserv Global Digital Commerce platform Connect Integration manual LAS Argentina and Uruguay Version: 2020-3 1 Connect Integration manual LAS Connect Integration manual LAS Version 2020-3 (IPG) Contents Getting Support 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Payment process options Checkout option ‘classic’ 4 Checkout option ‘combinedpage’ 5 3. Getting Started 5 Checklist 5 ASP Example 5 PHP Example 6 Amounts for test transactions 7 4. Mandatory Fields 8 5. Optional Form Fields 9 6. Using your own forms to capture the data 13 payonly Mode 13 payplus Mode 13 fullpay Mode 14 Validity checks 15 7. Additional Custom Fields 16 8. Data Vault 17 9. Recurring Payments 18 10. Transaction Response 19 Response to your Success/Failure URLs 19 Server-to-Server Notification 21 Appendix I – How to generate a hash 232 Appendix II – ipg-util.asp 253 Appendix III – ipg-util.php 276 Appendix IV – Currency Code List 287 Appendix V – Payment Method List 321 2 Connect Integration manual LAS Getting Support There are different manuals available for Fiserv’s eCommerce solutions. This Integration Guide will be the most helpful for integrating hosted payment forms or a Direct Post. For information about settings, customization, reports and how to process transactions manually (by keying in the information) please refer to the User Guide Virtual Terminal. If you have read the documentation and cannot find the answer to your question, please contact your local support team. 3 Connect Integration manual LAS 1. Introduction The Connect solution provides a quick and easy way to add payment capabilities to your website. -

Still at Risk | Security of Tenure and the Forced Eviction of Idps And

Still at risk Security of tenure and the forced eviction of IDPs and refugee returnees in urban Afghanistan Still at risk Security of tenure and the forced eviction of IDPs and refugee returnees in urban Afghanistan February 2014 Acknowledgements This report was developed and written by Caroline Howard (Afghanistan Country Analyst, IDMC) and Jelena Madzarevic (Housing, Land and Property Advisor, NRC Afghanistan). Special thanks to NRC Afghanistan Information, Counselling and Legal Assistance (ICLA) colleagues for their invaluable assistance in the collection and analysis of case information. Thanks also to Barbara McCallin, Senior HLP Advisor at IDMC; Monica Sanchez-Bermudez, NRC Oslo ICLA Advisor; Roel Debruyne, Protection and Advocacy Manager, NRC Afghanistan; Shoba Rao and Jan Turkstra of UN-HABITAT Afghanistan and Susan Schmeidl and Peyton Cooke from The Liaison Office for their advice and review of the report at different stages. Sven Richters, Michael Simpson, Frank Smith and Wesli Turner at IDMC provided further research assistance and comments. IDMC would also like to thank all those who made time to meet and talk to IDMC researchers in the field. Finally, thanks to Tim Morris for editorial assistance. Cover photo: An internally displaced person bears the winter cold in a camp in Kabul, Afghanistan. Credit: DRC/Eric Gerstner, January . Published by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and the Norwegian Refugee Council Chemin de Balexert - PO Box ¡ St. Olavs plass CH- Châtelaine (Geneva) Oslo, Norway Switzerland Tel: + ¡ Tel: + / Fax: + Fax: + ¡ www.internal-displacement.org www.nrc.no This publication was printed on paper from sustainably managed forests. Table of contents Acronyms and Abbreviations . -

Currency Code Currency Name Units Per EUR USD US Dollar 1,114282

Currency code Currency name Units per EUR USD US Dollar 1,114282 EUR Euro 1,000000 GBP British Pound 0,891731 INR Indian Rupee 76,833664 AUD Australian Dollar 1,596830 CAD Canadian Dollar 1,463998 SGD Singapore Dollar 1,519556 CHF Swiss Franc 1,097908 MYR Malaysian Ringgit 4,585569 JPY Japanese Yen 120,445338 CNY Chinese Yuan Renminbi 7,657364 NZD New Zealand Dollar 1,660507 THB Thai Baht 34,435083 HUF Hungarian Forint 325,394724 AED Emirati Dirham 4,092202 HKD Hong Kong Dollar 8,705685 MXN Mexican Peso 21,275509 ZAR South African Rand 15,449937 PHP Philippine Peso 56,970569 SEK Swedish Krona 10,508745 IDR Indonesian Rupiah 15576,638324 SAR Saudi Arabian Riyal 4,178559 BRL Brazilian Real 4,190947 TRY Turkish Lira 6,353929 KES Kenyan Shilling 115,893733 KRW South Korean Won 1311,898493 EGP Egyptian Pound 18,508337 IQD Iraqi Dinar 1326,662413 NOK Norwegian Krone 9,632916 KWD Kuwaiti Dinar 0,339171 RUB Russian Ruble 70,335592 DKK Danish Krone 7,465851 PKR Pakistani Rupee 179,387706 ILS Israeli Shekel 3,926669 PLN Polish Zloty 4,255048 QAR Qatari Riyal 4,055988 XAU Gold Ounce 0,000784 OMR Omani Rial 0,428442 COP Colombian Peso 3560,158642 CLP Chilean Peso 770,643233 TWD Taiwan New Dollar 34,639236 ARS Argentine Peso 47,788112 CZK Czech Koruna 25,516024 VND Vietnamese Dong 25847,134851 MAD Moroccan Dirham 10,697013 JOD Jordanian Dinar 0,790026 BHD Bahraini Dinar 0,418970 XOF CFA Franc 655,957000 LKR Sri Lankan Rupee 196,347604 UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia 28,564201 NGN Nigerian Naira 403,643263 TND Tunisian Dinar 3,212774 UGX Ugandan Shilling 4118,051290 -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

2017 Afghanistan Synthetic Drugs Situation Assessment

Afghanistan Synthetic Drugs Situation Assessment UNODC Global SMART Programme January 2017 CONTENTS PREFACE 3 ABBREVIATIONS 4 EXPLANATORY NOTES 5 INTRODUCTION 7 1. THE SYNTHETIC DRUG SITUATION IN AFGHANISTAN 8 A differentiated market for synthetic drugs 8 Manufacture and trafficking of methamphetamine 9 Methamphetamine prices 17 Methamphetamine use and treatment in Afghanistan 18 Synthetic drug use patterns: polydrug use and diverse modes of administration 21 Challenges in assessing the demand for synthetic drugs in Afghanistan 24 2. SYNTHETIC DRUGS IN SOUTH-WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA 26 The methamphetamine situation in South-Western and Central Asia 27 Methamphetamine manufacture in South-Western and Central Asia 31 3. CONCLUDING REMARKS 33 ANNEX I 34 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Afghanistan Synthetic Drugs Situation Assessment was prepared by the UNODC Research and Trend Analysis Branch (RAB), Laboratory and Scientific Section (LSS) under the supervision of its Chief, Justice Tettey. Core team Research, study preparation and drafting Abdul Subor Momand (National Consultant) Natascha Eichinger (SMART Vienna) Global SMART team Martin Raithelhuber Sabrina Levissianos Susan Ifeagwu Agata Rybarska Graphic design and maps Suzanne Kunnen Kristina Kuttnig The UNODC Global Synthetics Monitoring, Analysis, Reporting and Trends (SMART) Programme would like to thank the Government of Canada which made the development of this report possible. The UNODC Global SMART Programme is also grateful for the valuable contributions provided by the experts and officials -

Valūtas Kods Valūtas Nosaukums Vienības Par EUR EUR Par Vienību

Valūtas kods Valūtas nosaukums Vienības par EUR EUR par vienību USD US Dollar 1,218395 0,820752 EUR Euro 1,000000 1,000000 GBP British Pound 0,908551 1,100653 INR Indian Rupee 89,954543 0,011117 AUD Australian Dollar 1,614145 0,619523 CAD Canadian Dollar 1,571136 0,636482 SGD Singapore Dollar 1,626847 0,614686 CHF Swiss Franc 1,082267 0,923986 MYR Malaysian Ringgit 4,950320 0,202007 JPY Japanese Yen 126,052714 0,007933 Chinese Yuan CNY 7,976967 0,125361 Renminbi NZD New Zealand Dollar 1,727849 0,578754 THB Thai Baht 36,816359 0,027162 HUF Hungarian Forint 362,258064 0,002760 AED Emirati Dirham 4,474555 0,223486 HKD Hong Kong Dollar 9,445345 0,105872 MXN Mexican Peso 24,524602 0,040775 ZAR South African Rand 17,885380 0,055912 PHP Philippine Peso 58,559277 0,017077 SEK Swedish Krona 10,146394 0,098557 IDR Indonesian Rupiah 17334,350636 0,000058 SAR Saudi Arabian Riyal 4,568980 0,218867 BRL Brazilian Real 6,287178 0,159054 TRY Turkish Lira 9,336578 0,107106 KES Kenyan Shilling 133,001022 0,007519 KRW South Korean Won 1350,926114 0,000740 EGP Egyptian Pound 19,090840 0,052381 IQD Iraqi Dinar 1450,513132 0,000689 NOK Norwegian Krone 10,640818 0,093978 KWD Kuwaiti Dinar 0,371462 2,692065 RUB Russian Ruble 92,383585 0,010824 DKK Danish Krone 7,439463 0,134418 PKR Pakistani Rupee 195,617381 0,005112 ILS Israeli Shekel 3,937380 0,253976 PLN Polish Zloty 4,507902 0,221833 QAR Qatari Riyal 4,434957 0,225481 XAU Gold Ounce 0,000653 1530,480628 OMR Omani Rial 0,468473 2,134596 COP Colombian Peso 4221,486716 0,000237 CLP Chilean Peso 880,402069 0,001136 -

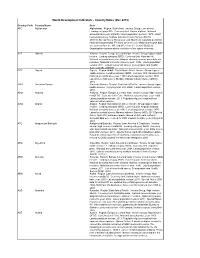

Undata WDI Metadata 2015 01 23.Xlsx

World Development Indicators - Country Notes (Dec 2014) Country Code Country Name Note AFG Afghanistan Afghanistan. Region: South Asia. Income Group: Low income. Lending category: IDA. Currency Unit: Afghan afghani. National accounts base year: 2002/03 Latest population census: 1979. Latest household survey: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2010/11.Special Notes: Fiscal year end: March 20; reporting period for national accounts data: FY (from 2013 are CY). National accounts data are sourced from the IMF and differ from the Central Statistics Organization numbers due to exclusion of the opium economy. ALB Albania Albania. Region: Europe & Central Asia. Income Group: Upper middle income. Lending category: IBRD. Currency Unit: Albanian lek. National accounts base year: Original chained constant price data are rescaled. National accounts reference year: 1996. Latest population census: 2011. Latest household survey: Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), 2008/09. DZA Algeria Algeria. Region: Middle East & North Africa. Income Group: Upper middle income. Lending category: IBRD. Currency Unit: Algerian dinar. National accounts base year: 1980 Latest population census: 2008. Latest household survey: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2012. ASM American Samoa American Samoa. Region: East Asia & Pacific. Income Group: Upper middle income. Currency Unit: U.S. dollar. Latest population census: 2010. ADO Andorra Andorra. Region: Europe & Central Asia. Income Group: High income: nonOECD. Currency Unit: Euro. National accounts base year: 1990 Latest population census: 2011. Population figures compiled from administrative registers.. AGO Angola Angola. Region: Sub-Saharan Africa. Income Group: Upper middle income. Lending category: IBRD. Currency Unit: Angolan kwanza. National accounts base year: 2002 Latest population census: 1970. Latest household survey: Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS), 2011.Special Notes: April 2013 database update: Based on IMF data, national accounts data were revised for 2000 onward; the base year changed to 2002. -

Influences of Devaluation in Foreign Currencies on the Performance Of

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 11, Issue 2, February-2020 935 ISSN 2229-5518 Influences of Devaluation in foreign currencies on the performance of local businesses in Afghanistan with reference to Pakistan’s currency (Rupee) –An empirical study of Jalalabad city. Hamayun Khan, Maneesha Ajula Abstract— The currency of Pakistan (Rupee) has been in circulation in the eastern and southeastern markets of Afghanistan. after the civil war intensified in Afghanistan in late 1992 and onwards, the Taliban militants took over control of the country’s agencies and eventually the whole government, as a result they laid off the contract with Russian firms to put out printing the Afghani notes they claimed were worthless. Besides, macro factors (e.g. political instability and foreign interference) have caused the country’s economy to steep, therefore the Afghani lost its value both in the regional and international markets. different Warlords in Afghanistan used to print their own introduced currencies without any formal approval and standard procedure of the state’s central bank (i.e. Da Afghanistan Bank). Therefore, people who were living across the Durand line were forced to start their daily transactions using Rupee which has caused Afghanistan to be financially, economically and politically relied on Pakistan. Ever since Rupee has dominated the Afghani in the eastern and south-eastern markets of Afghanistan. A survey was carried out to collect the required data in the city of Jalalabad using both primary and secondary