An Introduction to Intellectual Property Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Spirit April

The Greenfield Spirit Apr-May 2015 GREENFIELD’S COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER VOLUME 22.0 Visit the town website at http://www.greenfield-nh.gov/ for more information FREE TOWN MEETING RESULTS Please consult the green pages of your annual report for the text of the warrant articles. Article 1: Inside this issue Selectboard - Stephen Atherton Jr. 225th Anniversary ........................13 Fire Chief - David Hall Cloverly Farm CSA .......................6 Town Clerk - Dee Sleeper Emerald Ash Borer ....................9 Trustee of Trust Funds - 3 years - Kenneth Paulsen Food Pantry...................................6 Trustee of Trust Funds - 2 years - Vicki Norris Fire Chief’s Corner.........................5 Trustee of Trust Funds - 1 year - Linda Nickerson Free CPR Training .........................6 Library Trustee - 3 years - Jami Bascom Cemetery Trustee - 3 years - Margo Charig Bliss From the Recycling Center .............4 Planning Board - 3 years - Kenneth Paulsen Historical Society News..................3 Budget Committee - 3 years - Kevin Taylor Memorial Day Planning .................3 Budget Committee - 3 years - Myron Steere III Monadnock Roller Derby ...............6 Budget Committee - 2 years - Kenneth Paulsen Recreation..................................11 Budget Committee - 2 years - Norman Nickerson Roadside Round-Up .....................10 Budget Committee - 1 year - Susan Moller Spirit Deadlines......................6, back School Representative - Myron Steere III School Board Moderator - 3 years - Timothy Clark Stephenson Library -

September 1985, Vol. 8 Issue 1

THE SUNY COBLESKILL VOLUME 8 ISSUE ONE SEYf. '85 Welcome to Coby Welcome to Coby! My name is Christy Roe and I will be 'serving you as your Student Government President. I am very optimistic about the year ahead, and I hope that you are also. I would like to fake this opportunity to pass on to you a few of my thoughts. As you stepped from high school into college you learn about many new freedoms that you've never had before. Don't forget that with freedOI}1 comes responsibility, responsibilities to your school and to yourself. You paid good money to attend this school so take pride in being a part of Cobleskill College and take pride in yourself . College is the place where you further your education while at the same time meeting new people and doing new things. Respect is important in college life, not only should you respect others, but show some respect for yourself. Treat people the way in which you like to be tgreated and be sensitive to their feelings. We are a ll coming here as individuals with your own ideas and it's important to share them. As we learn from each other we also Recruitment Sta rts E arly: President Nea l Robbi ns is shown here· learn valuable lessons about ourselves. So stand up for what you receiving a welcom ing handshake fr om Orion Ha mchuk whose believe in! . mother, Linda L emback, is a m ember of the f r eshman class, Cobleskill has many opportunities in whic h you can become m ajoring in Nur se r y Managem en t . -

![Free Ratt Album Mp3 Download Weʼve Raised £0 to [(Download)] Full Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 Mp3 Album 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7842/free-ratt-album-mp3-download-we-ve-raised-%C2%A30-to-download-full-ratt-atlantic-years-1984-1990-mp3-album-2020-2557842.webp)

Free Ratt Album Mp3 Download Weʼve Raised £0 to [(Download)] Full Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 Mp3 Album 2020

free ratt album mp3 download Weʼve raised £0 to [(Download)] Full Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 Mp3 Album 2020. Crowdfunding is a new type of fundraising where you can raise funds for your own personal cause, even if you're not a registered nonprofit. The page owner is responsible for the distribution of funds raised. Story. [(Download)] Full Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 Mp3 Album 2020. Zip File! Download Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 Album 02.04,2020. [FulL.Album] Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990. Full Zip 02.04,2020. Is leak Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 Download 2020 [Zip Torrent Rar] Album #Full# Download Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 2020 Working Zip. [Mp3 @Zip@] Telecharger Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 Album Gratuit. |ZiP] Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 Album Download Full 2020. [#Download#] Ratt - Atlantic Years 1984-1990 Album Download. Zip-Torrent/Mp3 2020. Ratt Out Of The Cellar Remastered Rar. RATT's first five albums — 1984's 'Out of the Cellar'. First Five Albums Remastered For 'Original Album Series. Threads Tagged with ratt: User Name: Remember Me? DEFINATELY NOT REMASTERED. The only remastered Ratt cds are those same titles that are in the box (OOTC thru Detonator) which were released in Japan a couple of years ago. The Ratt Japanese mini-LPs from 2009 are pretty much. Just got my out of the cellar and dancing. They were remastered @ 24 and dithered to 16bit. Free download info for the Hard rock Glam metal album Ratt - Out Of The Cellar (SHM-CD Japan 2009 Remastered) (1984) compressed in.rar file format. -

A Sonoridade Das Bandas De Glam Metal Dos Anos 80 Com Foco Na Guitarra Elétrica Distorcida

VITOR ARAUJO MELLADO “CUM ON FEEL THE NOIZE”: A sonoridade das bandas de glam metal dos anos 80 com foco na guitarra elétrica distorcida São Paulo 2017 VITOR ARAUJO MELLADO “CUM ON FEEL THE NOIZE”: A sonoridade das bandas de glam metal dos anos 80 com foco na guitarra elétrica distorcida Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Bacharel em música com habilitação em composição do Instituto de Artes da Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Campus de São Paulo Orientador: Maurício Funcia de Bonis São Paulo 2017 VITOR ARAUJO MELLADO “CUM ON FEEL THE NOIZE”: A sonoridade das bandas de glam metal dos anos 80 com foco na guitarra elétrica distorcida Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso aprovado como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Bacharel em música com habilitação em composição do Instituto de Artes da Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Campus de São Paulo ________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Maurício Funcia De Bonis Instituto de Artes – Unesp - Orientador ________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Marcos José Cruz Mesquita Instituto de Artes – Unesp São Paulo,____de___________de 2017 Agradecimentos Agradeço minha família por me apoiar e incentivar. Bem como Maurício De Bonis por sua orientação. RESUMO O presente trabalho discorre acerca do surgimento do glam metal, destacando quais características foram inovadoras neste subgênero se comparado ao heavy metal contemporâneo e anterior a ele, mas também apontado suas influências, como o glam rock e o hard rock. Também contemplaremos o seu impacto na sociedade, americana a princípio, espalhando-se rapidamente pelo mundo, e a sonoridade empregada pelas principais bandas de glam metal de Los Angeles, Estados Unidos da América dos anos 80 nas linhas de guitarra elétrica de suas músicas, o que nos levará a observar a própria evolução da distorção da guitarra elétrica ao longo do tempo até aquele momento. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Royal Wood – Ghost Light • Rufus Wainwright

Royal Wood – Ghost Light Rufus Wainwright – Take All My Loves: 9 Shakespeare Sonnets André Rieu – Magic Of The Waltz Check out new releases in our Vinyl Section! New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI16-15 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 *Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Various Artists / Now! 26 Bar Code: Cat. #: 0254782454 Price Code: G Order Due: March 3, 2016 Release Date: April 1, 2016 6 02547 82454 7 File: Pop Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: 25 Key Tracks: SUPER SHORT SELL Key Points: National Major TV, Radio Online Advertising Campaign Now! Brand is consistently one of the strongest and best‐selling compilations every year The NOW! brand has generated sales of over 200 million albums worldwide Sold over 4 million copies in Canada since its debut. Includes: Justin Bieber – Sorry Selena Gomez ‐ Same Old Love Coleman Hell ‐ 2 Heads Shawn Mendes ‐ Stitches Ellie Goulding ‐ On My Mind Alessia Cara ‐ Here DNCE ‐ Cake By The Ocean Demi Lovato ‐ Confident Nathaniel Rateliff & The Night Sweats ‐ S.O.B Hedley ‐ Hello James Bay ‐ Let It Go Mike Posner ‐ I Took A Pill In Ibiza And more….. Also Available: Artist/Title: Various / Now! 25 Cat#: 0254750866 Price Code: JSP UPC#: 02547 50866 6 9 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Universal Music Canada Territory: Domestic Release Type: O For additional artist information please contact Nick at 416‐718‐4045 or [email protected] UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERS AL M USI C CA NAD A N EW RELEASE Artist/Title: THE STRUMBELLAS / HOPE (CD) Cat. -

3D in Your Face 44 Magnum 5 X 77 (Seventy Seven)

NORMALPROGRAMM, IMPORTE, usw. Eat the heat CD 12,00 District zero CD 29,00 The void unending CD 13,00 Restless and live - Blind rage Dominator CD 18,00 ANCIENT EMPIRE - live in Europe DCD 20,00 Female warrior CD & DVD 18,00 Eternal soldier CD 15,50 Russian roulette CD 12,00 Mermaid MCD 15,50 Other world CD 15,50 Stalingrad CD & DVD18,00 Other world CD & DVD 23,00 The tower CD 15,50 Stayin’ a life DCD 12,00 White crow CD 21,00 When empires fall CD 15,50 The rise of chaos CD 18,50 alle Japan imp. ANGEL DUST ACCID REIGN ALHAMBRA Into the dark past & bonustr. CD 15,50 Awaken CD 15,50 A far cry to you CD 26,00 official rerelease Richtung Within Temptation mit einem Japan imp. To dust you will decay - official guten Schuß Sentenced ALIVE 51 rerelease on NRR CD 15,50 ACCUSER Kissology - an Italian tribute to ANGEL MARTYR Dependent domination CD 15,50 the hottest band in the world CD 15,50 Black book chapter one CD 15,50 Diabolic CD 15,50 ALL SOUL´S DAY ANGELMORA The forlorn divide CD 15,50 Into the mourning CD 15,50 AIRBORN - Lizard secrets CD 15,50 Mask of treason CD 15,50 ACID ALLOY CZAR ANGEL WITCH Acid CD 18,00 Awaken the metal king CD 15,50 `82 revisited CD 15.50 3D IN YOUR FACE Engine beast CD 18,00 Moderater NWoBHM Sound zwischen Angel Witch - deluxe edition DCD 15,50 Faster and faster CD 15,50 Maniac CD 18,00 BITCHES SIN, SARACEN, DEMON, Eine tolle, packende Mischung aus SATANIC RITES gelegen. -

Internet Super-User Textbook Understanding the Internet Understanding the Internet

FOREWORD In November 2009, we spent many days at GetSmarter HQ brainstorming ideas for new online courses. During this time, we analysed our past students for clues on what courses we should be presenting next, and we realised that thousands of our past students represented some of the smartest people in the country. Was this because they had taken one of our online courses? Perhaps. But it quickly became clear to us that it was their use of the internet and its tools that set them apart from their peers. They were more effective, more efficient and smarter because they were already internet super- users. The fact that they took one of our online courses was simply because they could. So we decided to share the love by offering a course to help novice internet users become internet super-users. We quickly realised that a suitable textbook didn’t exist, and so we decided to develop one ourselves. My thanks and admiration go to Masha du Toit and Anna Malczyk, who worked many hours and completed hundreds of reviews to make this textbook the valuable resource that it is today. I’d also like to thank Jean-Paul van Belle for his guidance throughout the design of the book. If you are looking to become an internet super-user, good luck and have fun. My wish for you is that this textbook opens up a world of exciting First published January 2011 internet tools that enriches your life forever. By GetSmarter Publishing If you are a teacher and are looking to prescribe this textbook to your class, I am thrilled that you have chosen to work with us. -

Cudd Dissertation to Deposit

©2020 Michael Seth Cudd ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FUNCTIONAL AND LENGTHY: PREVAILING CHARACTERISTICS WITHIN SUCCESSFUL LONG SONGS By MICHAEL SETH CUDD A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Music Written under the direction of Christopher Doll And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Functional and Lengthy: Prevailing Characteristics within Successful Long Songs by MICHAEL SETH CUDD Dissertation Director: Christopher Doll Successful long popular songs consistently utilize formal structures and compositional techniques that are inherently particular to them. As a result, these recordings differ in more ways than simply length, because there are “long song” characteristics that distinguish this music. In order to better discuss these characteristics, it was important to develop a method for visually depicting songs in a manner that clearly outlines each groove. These “groove analyses” are used to discuss each piece of music in detail. As a result, groove is a primary point of discussion throughout this study, because most long song characteristics are directly linked to this quality within music. This type of analysis is explained in detail, and afterwards, it is utilized throughout much of the dissertation. It is also hypothetically possible that the structures and techniques in question can impact the listener’s perception of time when used outside of the context of a long song. A simple experiment was run in order to better understand how these concepts influence a person’s sense of duration, and the results were promising and demonstrated trends that merit further research. -

Suffolk County Legislature General Meeting Tenth Day

SUFFOLK COUNTY LEGISLATURE GENERAL MEETING TENTH DAY June 21, 2011 Verbatim Transcript MEETING HELD AT THE EVANS K. GRIFFING BUILDING IN THE MAXINE S. POSTAL LEGISLATIVE AUDITORIUM 300 CENTER DRIVE, RIVERHEAD, NEW YORK Verbatim Minutes Taken By: Alison Mahoney & Lucia Braaten - Court Reporters Verbatim Transcript Prepared By: Alison Mahoney & Lucia Braaten/Kim Castiglione - Legislative Secretary (*The meeting was called to order at 9:31 A.M.*) (The following testimony was taken by Alison Mahoney & Transcribed by Kim Castiglione, Legislative Secretary) D.P.O. VILORIA-FISHER: Mr. Clerk, please call the roll. (Roll called by Tim Laube, Clerk of the Legislature) LEG. ROMAINE: Present. LEG. SCHNEIDERMAN: Here. LEG. BROWNING: Here. LEG. MURATORE: Here. LEG. ANKER: Here. LEG. EDDINGTON: Here. LEG. MONTANO: (Not Present) LEG. CILMI: Here. LEG. BARRAGA: Here. LEG. KENNEDY: (Not present) LEG. NOWICK: Here. LEG. HORSLEY: Here. LEG. GREGORY: (Not present) LEG. STERN: Here. LEG. D'AMARO: Here. 2 LEG. COOPER: (Not present) D.P.O. VILORIA-FISHER: Here. P.O. LINDSAY: (Not present) MR. LAUBE: Twelve (ACTUAL VOTE: Thirteen). D.P.O. VILORIA-FISHER: Thank you, Mr. Clerk. There will be a Presentation of Colors by the Mattituck-Southold-Greenport Navy Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps recently named the most outstanding unit in the Northeast United States for the fifth successive year. Applause and Standing Ovation D.P.O. VILORIA-FISHER: The salute to the flag will be led by Legislator Jay Schneiderman. Salutation The invocation will be given by Father Edward Sheridan from Church of Saint Rosalie's Roman Catholic Church in Hampton Bays, a guest of Legislator Jay Schneiderman. -

VÖ-Datum: 1.2.2013

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] ROCK …ist eine große Schublade. In die passen hier kluger Ostküsten-Folk und Macho-Sounds aus dem Süden ebenso wie haariger Metal und sonnige Grooves von der Westküste. Und dazwischen tummeln sich auch noch drei ganz große Namen mit Legenden-Status mit jeweils fünf Alben, die in keiner Sammlung fehlen sollten… VÖ-Datum: 1.2.2013 10.000 MANIACS Die schimmernde, unmittelbar einnehmende Stimme von Natalie Merchant und die erfindungsreich gespielte Gitarre des inzwischen leider längst verstorbenen Robert Buck – das ist der magische Kern des Folk-Pop, den die 1981 in Jamestown, New York gegründete und nach einem Horror-Film (2.000 Maniacs) benannte Band auch zu einem durchaus unvermuteten kommerziellen Erfolg führte. Nachdem das Elektra-Debüt „The Wishing Chair“ 1985 den auch mal New Wave-inspirierten Rahmen mit Songs wie „Grey Victory“, „Maddox Table“ und „My Mother The War“ gleich überzeugend abgesteckt hatte, brachte „In My Tribe“ zwei Jahre später die erste US Top 40-Platzierung. Von Studioveteran Peter Asher (James Taylor, Linda Ronstadt) perfekt in Szene gesetzte Songs wie „Hey Jack Kerouac“ und der sozialkritische Impetus von „What’s The Matter Here“ oder „Gun Shy“ gehörten bald zur Grundausstattung jedes College-Campus. Mit ähnlichem Profil kletterte der Nachfolger „Blind Man’s Zoo“ 1989 sogar bis auf Platz 13 und erreichte Gold-Status. Zu ganz großer Form samt Bläsern, Streichern und Hits wie „These Are Days“ liefen die 10.000 Maniacs dann nochmal drei Jahre darauf mit „Our Time In Eden“ auf – ein prophetischer Titel, denn es sollte bereits das letzte Album der Band mit Natalie Merchant sein, die nach einer letzten, gemeinsamen Tour ihre Solo- Karriere startete. -

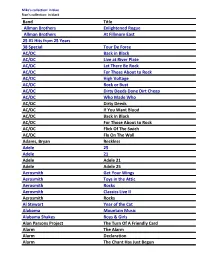

Band Title Allman Brothers Enlightened Rogue Allman

Mike's collection: in blue Stan's collection: in black Band Title Allman Brothers Enlightened Rogue Allman Brothers At Fillmore East 25 #1 Hits from 25 Years 38 Special Tour De Force AC/DC Back in Black AC/DC Live at River Plate AC/DC Let There Be Rock AC/DC For Those About to Rock AC/DC High Voltage AC/DC Rock or Bust AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC Who Made Who AC/DC Dirty Deeds AC/DC If You Want Blood AC/DC Back In Black AC/DC For Those About to Rock AC/DC Flick Of The Swich AC/DC Fly On The Wall Adams, Bryan Reckless Adele 25 Adele 21 Adele Adele 21 Adele Adele 25 Aerosmith Get Your Wings Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Rocks Aerosmith Classics Live II Aerosmith Rocks Al Stewart Year of the Cat Alabama Mountain Music Alabama Shakes Boys & Girls Alan Parsons Project The Turn Of A Friendly Card Alarm The Alarm Alarm Declaration Alarm The Chant Has Just Begun Mike's collection: in blue Stan's collection: in black Alarm The Deceiver Alarm Absolute Reality Alarm Spirit Of 76 Alarm Strength Alarm Presence Of Love Alarm Change Aldean, Jason Old Boots New Dirt Aldo Nova Subject Alice in Chains Black Gives Way to Blue Alice In Chains Black Gives Way To Blue Alice In Chains The Devil Put Dinosaurs Here Allman Brothers Live at Beacon Theatre Allman Brothers Eat a Peach Allman Brothers Beginnings Allman Brothers Brothers and Sisters Allman Brothers The Allman Brothers Band Allman Brothers Live at Fillmore East Allman Brothers Duane Allman Anthology Allman Brothers Eat A Peach Allman Brothers Beginnings Allman Brothers The Greg Allman