The Price of Obedience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 High Street, Builth Wells 01982 553004 [email protected]

14 High Street, Builth Wells 01982 553004 [email protected] www.builthcs.co.uk Builth Wells Community Services provided: Support was established in Community Car scheme 1995 and is a registered charity and Company Limited Prescription Delivery by Guarantee. The aims of Befriending Community Support are to Monthly Outings provide services, through our team of 98 Volunteers, which Lunch Club help local people to live “Drop in” information & healthy independent lives signposting within their community and Volunteer Bureau working to be a focal point for with volunteering and general information. Powys Volunteer Centre to promote Volunteering We are demand responsive. All services are accessed by In 2013 we became a Company Limited by requests from individuals, Guarantee , retaining our family members or support charitable status agencies, we can add to statutory service provision; offering the extras that are We also have our own important in people’s lives. Charity Shop at 39 High Street, Builth Wells The office is open 9.30a.m – 1p.m Monday—Friday 2 Organisations 4 Churches 12 Community Councils 14 Health & Social Care 17 Schools 20 Leisure & Social Groups 22 Community Halls 28 Other Contacts 30 Powys Councillors 34 Index 36 3 Action on Hearing Loss Cymru Address: Ground Floor, Anchor Court North, Keen Road, Cardiff, CF24 5JW Tel: 02920 333034 [Textphone: 02920 333036] Email: [email protected] Website: www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk Age Cymru Powys Address: Marlow, South Crescent, Llandrindod, LD1 5DH Tel: 01597 825908 Email: -

Ffairfach Gwynfe Road, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire, SA19 6YU Offers in the Region of £565,000

Penycae Ffairfach Gwynfe Road, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire, SA19 6YU Offers in the region of £565,000 A Superb Residential Holding of 18 acres set in glorious location within the Brecon Beacons National Park and just 3 miles from the Country Market town of Llandeilo and commanding wonderful views over the rolling landscape of the Towy Valley and surrounding hillsides. The property comprises an attractive Country residence which has been the subject of much extension and refurbishment over time to provide a character home with many lovely features and offers the following versatile accommodation: Reception Hall; Utility Room; Kitchen/Living Room with Stanley Waterford range; Sitting Room with feature fireplace; Sun Lounge; 2 Ground floor Bedrooms; Bathroom; Magnificent first floor Master Bedroom with en suite Bathroom and Dressing Room. Oil fired central heating. Upvc Double Glazing. Cloaks/Boiler Room. Sweeping driveway leading to spacious courtyard around which the buildings are arranged which provide Workshops, Garages and Implement Stores. Superb landscaped grounds. Pasture paddocks and Mature woodland. Outstanding - book an appointment to view today Ffairfach Gwynfe Road, Llandeilo, SA19 6YU KITCHEN/LIVING ROOM 7'4" x 9'10" (2.26m x 3.00m) LOUNGE 16'11" x 16'0" (5.18m x 4.88m) Stainless steel sink unit with chrome mixer tap. Granite work Multi-fuel stove in feature fireplace with back boiler for domestic surface and surround. Ceramic hob with extractor hood above. hot water on slate hearth. Exposed bresumer beam. Exposed Caple combination microwave and conventional oven. Neff ceiling beams. Wall recess. Wall lights. Cast iron column dishwasher. Fitted fridge. Attractive Stanley Waterford oil fired radiator. -

Source Pack Group 1. Monument Found on the A4069 Between

Source pack group 1. Monument found on the A4069 between Llangadog and Brynamman on the Black Mountain. Workers used horse and cart to transport heavy loads. Travellers on the A4069 journeying over the Black Mountain between Llangadog and Brynamman may have noticed a roadside monument commemorating the death of David Davies of Gwynfe. The monument stands in a fascinating and strikingly beautiful landscape of limestone quarries and lime kilns within the Brecon Beacons National Park. (Dyfed Archaeological Trust) Source pack 2 At an average of 2mph it would take a horse with a cart 30 minutes to travel one mile. A five mile journey would take 2½ hours. www.ultimatehorsesite.com Advert for Lime from the Carmarthen Journal An abandoned lime kiln on the Black Mountain Many local smallholders and cottagers would have full time employment at the quarries and this would entail walking to and from work each day. Some however who lived further away would have to walk for many miles to the quarry on a Sunday night in readiness for an early Monday morning start and return home the following Friday in the late afternoon. They would take enough food with them for the week and their provisions would include home reared ham and bacon, eggs, bread, tea and vegetables. Mr Tom Williams of Myddfai Source pack 3 Llangadock Fatal accident – As Mr D Davies, Junior, of Glynclawdd Gwynfe, was driving an empty gambo on the Black Mountain on Wednesday afternoon, the horses became startled and dashed off. The unfortunate young man was thrown out, and though assistance was at once forthcoming he expired without a word. -

Carmarthenshire Revised Local Development Plan (LDP) Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Scoping Report

Carmarthenshire Revised Local Development Plan (LDP) Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Scoping Report Appendix B: Baseline Information Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 1. Sustainable Development 1.1 The Carmarthenshire Well-being Assessment (March 2017) looked at the economic, social, environmental and cultural wellbeing in Carmarthenshire through different life stages and provides a summary of the key findings. The findings of this assessment form the basis of the objectives and actions identified in the Draft Well-being Plan for Carmarthenshire. The Assessment can be viewed via the following link: www.thecarmarthenshirewewant.wales 1.2 The Draft Carmarthenshire Well-being Plan represents an expression of the Public Service Board’s local objective for improving the economic, social, environmental and cultural well- being of the County and the steps it proposes to take to meet them. Although the first Well- being Plan is in draft and covers the period 2018-2023, the objectives and actions identified look at delivery on a longer term basis of up to 20-years. 1.3 The Draft Carmarthenshire Well-being Plan will focus on the delivery of four objectives: Healthy Habits People have a good quality of life, and make healthy choices about their lives and environment. Early Intervention To make sure that people have the right help at the right time; as and when they need it. Strong Connections Strongly connected people, places and organisations that are able to adapt to change. Prosperous People and Places To maximise opportunities for people and places in both urban and rural parts of our county. SA – SEA Scoping Report – Appendix B July 2018 P a g e | 2 Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 2. -

1 ANTIQUARY SUBJECTS: 1984 – 2019 Compiled by Jill Davies by Place

ANTIQUARY SUBJECTS: 1984 – 2019 compiled by Jill Davies By place: LOCATION AUTHOR SUBJECT Aberglasney Joyner, Paul John Dyer 1995 Abergwili Davies, J D Bishop Lord George Murray 2001 Abergwili Jones, Anthea Bishop Yorke 1774 2002 Abergwili various Merlin's Hill 1988 Abergwili, Bryn Myrddin Wells, Terry Nature diary 2012 Abermarlais Turvey, Roger Jones family 1558, 1586 2018 Abermarlais Turvey, Roger Jones family 1588, 1604 2019 Aman Valley Mathews, Ioan Trade Unions 1996 Amman Valley Walters, Huw & Jones, Bill Emigrants to Texas 2001 Ammanford Walters, Huw Amanwy 1999 Ammanford Davies, Roy Dunkirk evacuation 2003 Ammanford/Glanaman Walters, Huw Emma Goldman 2003 Black Mountain Ward, Anthony Nant Gare valley settlement 1995 Brechfa Prytherch, J & R Abergolau Prytherchs 2004 Brechfa Rees, David Brechfa Forest 2001 Brechfa Rees, David Forest of Glyncothi 1995 Brechfa Morgan-Jones, D Morgan-Jones family 2006 Broad Oak Rees, David Cistercian grange, Llanfihangel Cilfargen 1992 Brynamman Beckley, Susan Amman Iron Company 1995 Brynamman Evans, Mike Llangadog road 1985 Brynamman Jones, Peter Chapels 2015 Burry Port Davis, Paul Lletyrychen 1998 Burry Port Bowen, Ray Mynydd Mawr railway 1996 1 Capel Isaac Baker-Jones Chapel/Thomas Williams 2003 Carmarthen Dale-Jones, Edna 19C families 1990 Carmarthen Lord, Peter Artisan Painters 1991 Carmarthen Dale-Jones, Edna Assembly Rooms, Coffee pot etc 2002 Carmarthen Dale-Jones, Edna Waterloo frieze 2015 Carmarthen James, Terry Bishop Ferrar 2005 Carmarthen Davies, John Book of Ordinances 1993 Carmarthen -

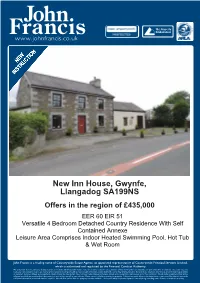

New Inn House, Gwynfe, Llangadog SA199NS

New Inn House, Gwynfe, Llangadog SA199NS Offers in the region of £435,000 • EER 60 EIR 51 • Versatile 4 Bedroom Detached Country Residence With Self Contained Annexe • Leisure Area Comprises Indoor Heated Swimming Pool, Hot Tub & Wet Room John Francis is a trading name of Countrywide Estate Agents, an appointed representative of Countrywide Principal Services Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. We endeavour to make our sales details accurate and reliable but they should not be relied on as statements or representations of fact and they do not constitute any part of an offer or contract. The seller does not make any representation to give any warranty in relation to the property and we have no authority to do so on behalf of the seller. Any information given by us in these details or otherwise is given without responsibility on our part. Services, fittings and equipment referred to in the sales details have not been tested (unless otherwise stated) and no warranty can be given as to their condition. We strongly recommend that all the information which we provide about the property is verified by yourself or your advisers. Please contact us before viewing the property. If there is any point of particular importance to you we will be pleased to provide additional information or to make further enquiries. We will also confirm that the property remains available. This is particularly important if you are contemplating travelling some distance to view the property. HC/WJ/59139/300518 Ceramic tiled floor, single panel Double glazed sliding sash window radiator, 2 double panelled to front, single panel radiator. -

Constituency – Carmarthen East and Dinefwr: Polling District Polling

Constituency – Carmarthen East and Dinefwr: Polling District Polling Place Total Electorate(those electors receiving a postal vote) A Gellimanwydd Hall, 1004 (227) Ammanford AA Abergwili Church Hall, 560 (115) Ammanford AB Peniel Community Room, 520 (106) Peniel AC Whitemill Inn, Whitemill 220 (63) AM Cenarth Church, Cenarth 346 (86) AN Capel Iwan Community 464 (106) Centre, Capel Iwan AY Cefneithin/Foelgastell 1276 (271) Welfare Hall AZ Drefach Welfare Hall, 970 (238) Drefach B Ammanford Pensioners’ 886 (289) Hall, Ammanford BA Gorslas Church Hall, 1392 (347) Gorslas BE Llanarthney Village Hall, 642 (169) Llanarthne BH Y Neuadd Fach, 774 (207) Porthyrhyd BI Mynyddcerrig 216 (48) Workingmen’s Club BM St. Anne’s Church Hall, 907 (219) Cwmffrwd BN Llandyfaelog Welfare Hall 238 (54) BO Llanfihangel Ar Arth 540 (126) School Hall BP Pencader Pavilion, 1070 (250) Pencader BQ Neuadd Yr Eglwys, 75 (18) Abergorlech BR Brechfa Church Hall, 191 (42) Brechfa BS Gwernogle Chapel Vestry 133 (49) BU Saron Chapel Vestry 720 (229) BV Pentrecwrt Village Hall 1005 (286) BW Red Dragon Hall, Felindre 971 (199) BX Yr Aelwyd, Tregynnwr 827 (281) BY Yt Aelwyd, Tregynnwr 1262 (337) BZ Carway Welfare Hall 827 (180) C The Hall, Nantlais 1036 (216) CB Llangyndeyrn Church Hall 619 (146) Polling District Polling Place Total Electorate(those electors receiving a postal vote) CC Salem Vestry, Four 228 (66) Roads CD Pontyates Welfare Hall 1148 (309) CG Llanllawddog Church Hall 580 (195) CH Nonni Chapel Vestry, 548 (123) Llanllwni CM Aberduar Chapel Vestry 970 (200) CN -

Ministry Area Brochure

The Placeholder Next Steps Forming Ministry Areas Diocese of Swansea and Brecon Summer 2014 From Bishop John … Dear Friends, In this booklet you’ll find the pattern of Ministry Areas by means of which, as they come into being, the Diocese will renew and develop its ministry. This marks the end of a lengthy period of prayerful consultation to which everybody in the Diocese had opportunities to contribute. Ministry Areas, adopted by the whole Church in Wales as the pattern for the future, offer us a fresh and exciting opportunity to renew the ways in which to minister in the communities where we are set. They offer a way of collaborative working, commended by the New Testament, with communities of disciples, lay and ordained, sharing ministry, growing in faith and into the image of Christ, witnessing to those around, and working to create new disciples. Whatever our present way of doing things might be, doing what we’ve always done is not an option however familiar or comfortable that might be. We will commit to a 'group practice' model for collaborative ministry and mission, with local churches working together in partnerships across familiar boundaries to enrich relationships and to share talents, gifts and resources. Instead of offering just one form and style across an area, we will offer a variety of worship and other opportunities, with a common aim of building a stronger, sustainable and more effective church which looks not only down the aisle but also out there into the community. It is intended that the current eleven Area Deaneries are revised to four with the designated Ministry Areas grouped into one of the new Deaneries. -

Sustainability Appraisal Report of the Deposit LDP November 2019

Carmarthenshire Revised Local Development Plan (LDP) Sustainability Appraisal Report of the Deposit LDP November 2019 1. Introduction This document is the Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Report, consisting of the joint Sustainability Appraisal (SA) and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA), of Carmarthenshire Council’s Deposit Revised Local Development Plan (rLDP).The SA/SEA is a combined process which meets both the regulatory requirements for SEA and SA. The revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan is a land use plan which outlines the location and quantity of development within Carmarthenshire for a 15 year period. The purpose of the SA is to identify any likely significant economic, environmental and social effects of the LDP, and to suggest relevant mitigation measures. This process integrates sustainability considerations into all stages of LDP preparation, and promotes sustainable development. This fosters a more inclusive and transparent process of producing a LDP, and helps to ensure that the LDP is integrated with other policies. This combined process is hereafter referred to as the SA. This Report accompanies, and should be read in conjunction with, the Deposit LDP. The geographical scope of this assessment covers the whole of the County of Carmarthenshire, however also considers cross-boundary effects with the neighbouring local authorities of Pembrokeshire, Ceredigion and Swansea. The LDP is intended to apply until 2033 following its publication. This timescale has been reflected in the SA. 1.1 Legislative Requirements The completion of an SA is a statutory requirement for Local Development Plans under Section 62(6) of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 20041, the Town and Country Planning (LDP) (Wales) Regulations 20052 and associated guidance. -

Road Number Road Description A40 C B MONMOUTHSHIRE to 30

Road Number Road Description A40 C B MONMOUTHSHIRE TO 30 MPH GLANGRWYNEY A40 START OF 30 MPH GLANGRWYNEY TO END 30MPH GLANGRWYNEY A40 END OF 30 MPH GLANGRWYNEY TO LODGE ENTRANCE CWRT-Y-GOLLEN A40 LODGE ENTRANCE CWRT-Y-GOLLEN TO 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL A40 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL TO CRICKHOWELL A4077 JUNCTION A40 CRICKHOWELL A4077 JUNCTION TO END OF 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL A40 END OF 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL TO LLANFAIR U491 JUNCTION A40 LLANFAIR U491 JUNCTION TO NANTYFFIN INN A479 JUNCTION A40 NANTYFFIN INN A479 JCT TO HOEL-DRAW COTTAGE C115 JCT TO TRETOWER A40 HOEL-DRAW COTTAGE C115 JCT TOWARD TRETOWER TO C114 JCT TO TRETOWER A40 C114 JCT TO TRETOWER TO KESTREL INN U501 JCT A40 KESTREL INN U501 JCT TO TY-PWDR C112 JCT TO CWMDU A40 TY-PWDR C112 JCT TOWARD CWMDU TO LLWYFAN U500 JCT A40 LLWYFAN U500 JCT TO PANT-Y-BEILI B4560 JCT A40 PANT-Y-BEILI B4560 JCT TO START OF BWLCH 30 MPH A40 START OF BWLCH 30 MPH TO END OF 30MPH A40 FROM BWLCH BEND TO END OF 30 MPH A40 END OF 30 MPH BWLCH TO ENTRANCE TO LLANFELLTE FARM A40 LLANFELLTE FARM TO ENTRANCE TO BUCKLAND FARM A40 BUCKLAND FARM TO LLANSANTFFRAED U530 JUNCTION A40 LLANSANTFFRAED U530 JCT TO ENTRANCE TO NEWTON FARM A40 NEWTON FARM TO SCETHROG VILLAGE C106 JUNCTION A40 SCETHROG VILLAGE C106 JCT TO MILESTONE (4 MILES BRECON) A40 MILESTONE (4 MILES BRECON) TO NEAR OLD FORD INN C107 JCT A40 OLD FORD INN C107 JCT TO START OF DUAL CARRIAGEWAY A40 START OF DUAL CARRIAGEWAY TO CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JCT A40 CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JUNCTION TO END OF DUAL CARRIAGEWAY A40 CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JUNCTION TO BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT A40 BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT TO CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JUNCTION A40 BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT SECTION A40 BRYNICH ROUNABOUT TO DINAS STREAM BRIDGE A40 DINAS STREAM BRIDGE TO BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT ENTRANCE A40 OVERBRIDGE TO DINAS STREAM BRIDGE (REVERSED DIRECTION) A40 DINAS STREAM BRIDGE TO OVERBRIDGE A40 TARELL ROUNDABOUT TO BRIDLEWAY NO. -

Bwthyn Y Bont Llanddeusant Gwynfe Llangadog Carmarthenshire Price

Bwthyn Y Bont Llanddeusant Gwynfe Llangadog Carmarthenshire SA19 9TA Price £125,000 • A Deceptively Spacious 3 Bedroom (2 Ensuite) Semi Detached Cottage Style Bungalow • LPG Central Heating & UPVC Double Glazing • Open Plan Lounge/Kitchen/Diner & Conservatory • Jack & Jill Wet Room Shower & Bathroom • Gravelled Off Road Parking Area To Side • Situated On The Edge of The Beautiful Brecon Beacons • Ideal Investment Property or Holiday Home • NO CHAIN Viewing: 01558 823 601 Website: www.ctf-uk.com Email: [email protected] General Description EPC Rating: E50 Important notice Clee, Tompkinson & Francis, (CTF) their clients and any joint agents give notice that 1: They are not authorised to make or give any representations or warranties A semi detached cottage style bungalow, situated in a rural location on the edge of the Black Mountain in the in relation to the property either here or elsewhere, either on their own behalf or on behalf of their client or otherwise. They assume no responsibility for any Brecon Beacons National Park, renowned for its coutryside walks and out door activities. statement that may be made in these particulars. These particulars do not form part of any offer or contract and must not be relied upon as statements or representations of fact. 2: Any areas, measurements or distances are approximate. The text, photographs and plans are for guidance only and are not necessarily comprehensive. It should not be assumed that the property has all necessary planning, building regulation or other consents and CTF have not tested any services, equipment or facilities. Purchasers must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise. -

Agricultural Notifications , Item ENC6 PDF 66 KB

APPLICATIONS DELEGATED TO THE NATIONAL PARK OFFICERS App No. Grid Ref. Applicant, proposal, type, address Decision Date Issued Decision Type 18/16170/AGR N: 212417 Mr David Daniel for implement shed, AGR 26 June 2018 Delegated E: 278338 steel frame (Agricultural Notification) at Permitted Decision Pensarn, Lower Cwmtwrch, Swansea Developm Powys SA9 2QL ent 18/16173/AGR N: 222605 Mr Barry Smith for Timber shed for AGR 17 July 2018 Delegated E: 266725 safe storage of tools, tea making, Permitted Decision washing facilities (Agricultural Developm Notification) at Cynthia Wood, Off ent Gwynfe Road, Ffairfach Llandeilo SA19 6YU 18/16174/AGR N: 222605 Mr Laurence Goode for Timber shed AGR 22 June 2018 Delegated E: 266725 for safe storage of tools, tea making, Permitted Decision washing facilities (Agricultural Developm Notification) at Cynthia Wood, Off ent Gwynth Road, Ffairfach Llandeilo Carmarthenshire SA19 6YU 18/16201/AGR N: 222526 Mr Rodney Dukes for Agricultural plant AGR 27 June 2018 Delegated E: 275996 and machinery building (Agricultural Permitted Decision Notification) at Pant Y Turnor, Developm Llangadog, Carmarthenshire SA19 9TN ent 18/16203/AGR N: 222040 Mr Christian Egeler for Barn/ covered AGR 29 June 2018 Delegated E: 266018 sheep run (Agricultural Notification) at Permitted Decision Land Opposite Tir Y Lan Farm , Gwynfe Developm Road, Ffairfach Llandeilo ent Carmarthenshire SA19 6YU 18/16269/AGR N: 231278 Mr Simon Mead for The proposal is for AGR 20 July 2018 Delegated E: 278348 access to allow woodland management Permitted Decision activities i.e. thinning, cleaning, other Developm forest management activities, which are ent necessary to develop the woodland.