A Case Study of Corn Sales: Harston Manor’S Corn Book 1823-42

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Cambridge.] Haslingfield](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7405/cambridge-haslingfield-17405.webp)

Cambridge.] Haslingfield

[CAMBRIDGE.] HASLINGFIELD. 60 [POST OFFICE Smith Thomas Hayden, miller & farmer Tuck Arthur, carrier Watson Lydia (Mrs.), farmer Stockbridge J onathan, grocer & linen Tuck Thomas, Waggon~ Horses Wedd Christopher, saddler & harness draper Wallis William, farmer maker Stockbridge William, wheelwright Wallman Lydia (Mrs.), butcher, land~ Wilmott William, miller Thompson Charles, brewer & cooper owner & farmer Wisby Allen, boot & shoe maker 'l'rigg William, corn merchant & farmer Watson John, farmer Wisby William, farmer HASLINGFIELD is a parish, 2 miles north from the Warr is lord of the manor and principal landowner. The Harston station, 55 from London, and 5~ south-west-by- soil is chalky and clay; subsoil, chalk and clay. 1'he chief south from Cambridge, bounded on the east by the river corps are wheat, beans and oats. The population in 1861 Cam, in the hundred of Wetherley, union of Chesterton, was 762 r the area is 2,527 acres. county court district of Cambridge, rural deanery of Bar- ton, and archdeaconry and diocese of Ely. The church of PosT 0FFICE.-James Lovett, sub-postmaster. J"etters All Saints, erected in 1352, is in the Early English style: arrive from Cambridge at 8.45 a.m.; dispatched at 5.20 it has a fine square tower containing 5 bells and clock, spire, p.m. The nearest money order office is at Cambridge chancel, nave, aisles, and porch. The living is a vicarage, ScHooLs:- yearly value £651, with residence, in the gift of John National (boys & girls), .Mitchell, Esq.; and held by the Rev. George Cowdell Infant, Clements, M.A., of Ernmanuel College, Cambridge. -

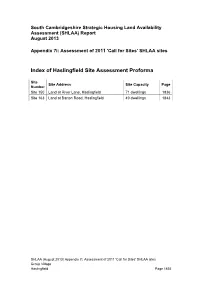

Index of Haslingfield Site Assessment Proforma

South Cambridgeshire Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) Report August 2013 Appendix 7i: Assessment of 2011 'Call for Sites' SHLAA sites Index of Haslingfield Site Assessment Proforma Site Site Address Site Capacity Page Number Site 150 Land at River Lane, Haslingfield 71 dwellings 1836 Site 163 Land at Barton Road, Haslingfield 49 dwellings 1843 SHLAA (August 2013) Appendix 7i: Assessment of 2011 'Call for Sites' SHLAA sites Group Village Haslingfield Page 1835 South Cambridgeshire Local Development Framework Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) Site Assessment Proforma Proforma July 2012 Created Proforma Last July 2012 Updated Location Haslingfield Site name / Land at River Lane address Category of A village extension i.e. a development adjoining the existing village site: development framework boundary Description of promoter’s Approximately 100 houses proposal Site area 3.15ha (hectares) Site Number 150 The site is on the eastern edge of Haslingfield. The western boundary of the site is adjacent to the rear gardens of houses in Cantelupe Road. A byway - River Lane follows part of the southern boundary from Cantelupe Road before it becomes a bridleway, which Site description continues eastward alongside the River Rhee. A track follows most & context of the eastern boundary of the site. There is open countryside to the north. The flood plain of the River Cam or Rhee is to the east and south east of the site. To the south west of the site is the Haslingfield recreation ground. The site is an arable field. Current or last Agriculture use of the site Is the site Previously No Developed Land? Allocated for a non-residential use in the No current development plan? Planning None history Source of site Site suggested through call for sites SHLAA (August 2013) Appendix 7i: Assessment of 2011 'Call for Sites' SHLAA sites Group Village Page 1836 Site 150 Land at River Lane, Haslingfield Tier 1: Strategic Considerations The site is within the Green Belt. -

Rectory Farm BARRINGTON, CAMBRIDGE

RectoRy FaRm BARRINGTON, CAMBRIDGE RectoRy FaRm 6 HASLINGFIELD ROAD, BARRINGTON, CAMBRIDGE, CB22 7RG An attractive Grade II listed village house with extensive period outbuildings in a superb position next to the church Reception hall, sitting room, family room, vaulted drawing room, kitchen/dining room, rear hall, utility room, pantry, cloaks w.c. First floor – 4 double bedrooms, family bathroom, shower room, Second floor – 2 attic rooms Extensive range of traditional outbuildings comprising double-sided open bay cart lodge, former hay barn, cow shed, brick barn. Attractive gardens and grounds, ornamental pond with “Monet” style arched bridge. In all 1.27 acres Savills Cambridge Unex House, 132-134 Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 8PA Contact: James Barnett BA (Hons) MRICS [email protected] 01223 347 147 www.savills.co.uk Situation Rectory Farm is set behind the historic All Saints Parish Church in the north-eastern corner of the popular and attractive South Cambridgeshire village of Barrington. Well known for having the largest village green in England, the village has good facilities including a shop/post office, football and cricket pitches, a popular pub/restaurant and a primary school. Secondary schooling is available at Melbourn Village College and there is also a wide selection of independent schooling available in Cambridge. Further amenities are in Melbourn (4 miles), Harston (3.3 miles) and the market town of Royston, 7 miles to the south-west. More comprehensive shopping, recreational and cultural facilities are available in the high tech university city of Cambridge which is 8 miles to the north east. For the commuter there are mainline rail links to Cambridge and London King’s Cross from local stations at either Shepreth (1.8 miles) and Foxton (2 miles) to the south and direct services from Royston into London King’s Cross (from 38 minutes). -

Index of Thriplow Site Assessment Proforma

South Cambridgeshire Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) Report August 2013 Appendix 7i: Assessment of 2011 'Call for Sites' SHLAA sites Index of Thriplow Site Assessment Proforma Site Site Address Site Capacity Page Number Site 016 The Grain Store, Lodge Road, Thriplow 50 dwellings 2148 Land west of Rectory Farm, Middle Street, Site 062 55 dwellings 2156 Thriplow Site 063 Land east of Farm Lane, Thriplow 99 dwellings 2164 SHLAA (August 2013) Appendix 7i: Assessment of 2011 'Call for Sites' SHLAA sites Group Village Thriplow Page 2147 South Cambridgeshire Local Development Framework Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) Site Assessment Proforma Proforma July 2012 Created Proforma Last July 2012 Updated Location Thriplow Site name / The Grain Store, Lodge Road address Category of A village extension i.e. a development adjoining the existing village site: development framework boundary Description of promoter’s 30 dwellings proposal Site area 1.84ha (hectares) Site Number 016 The site is located on the western edge of Thriplow south of Fowlmere Road and west of Lodge Road. There is a residential use adjoining the southern boundary. There is an area of open space Site description used as the village cricket ground to the east. To the north and west & context is open farmland. The site consists of a collection of agricultural buildings surrounded by hard standing. Current or last Grain store / Revivals (an MOT test centre) use of the site Is the site Previously Northern part of site with grain stores = No Developed MOT test centre =yes Land? Allocated for a non-residential use in the No current development plan? LDF 2006 – Objection Site 123 Planning The site was considered for residential development and no change history was recommended by the inspector. -

Project Summary List

Appendix 1: Project Summary List River Type Status Cost Detail Approach landowners and carry out walkover survey especially of reaches rarely accessed. Combine with information about the Bassingbourn stream Investigation R £5k stream and reasons to buffer (potential joint project with FWAG East) Bassingbourn stream Restoration R £15k Bank reprofiling and stabilisation, gravel placement, desilting around the springs Bassingbourn stream Restoration R £10k Lower reaches (longer term) to have gravel placement, brash ledges to enhance in-channel sinuosity and tree hinging Bassingbourn stream Daylighting R £20k Work with Bassingbourn Barracks (longer term) to improve habitat and where possible remove culverts on development site Cam Gt Chesterford-A505 Investigation R £2k Assessment of the barrier to fish movements posed by the mills and other structures Cam Gt Chesterford-A506 Restoration R £10k Dig ‘n dump in combination with levee removal and bank re-grading to push the banks down into the channel margins Cam Gt Chesterford-A507 Restoration A £2k Community-based habitat improvement work at Wellcome Trust site Cam Gt Chesterford-A508 Tree work R £2k Tree work to increase cover at, and below, water level (tree-hinging) Feasibility study for wetland creation on the Huawei site near the railway line, intercepting water from the ditch before it reaches the Cam A505 - Hauxton Investigation R £10k river Cam A505 - Hauxton Restoration R £15k Gravel placement downstream of gravel riffle on Huawei site to extend existing habitat, coupled with tree hinging/LWM placement Cam A505 - Hauxton Restoration R £10k Gravel placement elsewhere (several suitable sites exist) Cam A505 - Hauxton Tree work R £500-£2k Tree hinging and placement of LWM (many suitable sites) especially where pools and riffles are developing naturally Assess water levels at Dernford Fen, in particular whether there is a control structure. -

Land at 13 Harston Road, Newton, Cambridge CB22 7PA

Land at 13 Harston Road, Newton, Cambridge CB22 7PA A rare and exciting opportunity to acquire a secluded development site, with planning consent for a substantial detached barn style property set in grounds approaching 1.75 acres. Guide Price £825,000 Freehold LOCATION TENURE AND POSSESSION The site is for sale freehold with vacant possession on completion. Newton is a favoured South Cambridgeshire village nestling in glorious open undulating METHOD OF SALE countryside just 7 miles south of Cambridge. There is a lively social community centred around The Queens Head Public House and the village social club. Nearby Shelford and Sawston provide Redmayne Arnold & Harris have instructions to place the property on the open market with good shopping facilities. Royston is about 7 miles south and there are mainline stations to both a view to selling it at the best consideration which can be achieved as a result of a marketing London Liverpool Street and Kings Cross within a few miles. campaign. THE OPPORTUNITY The site is available on an unconditional basis by private treaty. This unique opportunity will be attractive to those looking to build an individual property in a SERVICES private setting and would be ideal for those seeking to create an equestrian facility. The site is edged on two boundaries by mature trees and established hedge line, making a perfect We are informed that currently no services are connected to the site. backdrop to the site. There may be some longer term hope value for future development of the site subject to planning permission. STATUTORY AUTHORITIES THE SITE South Cambridge District Council The site (Lot 1, edged in red on the plan) is tucked away in a secluded location, overlooking FURTHER INFORMATION fields/paddocks, behind existing properties on Town Street. -

Notice of Poll

NOTICE OF POLL South Cambridgeshire District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Little Gransden Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of Parish Councillors for Little Gransden will be held on Thursday 5 May 2016, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of Parish Councillors to be elected is five. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) BOURNE The Nook, 6 Primrose Self-Employed Maureen S Poole (+) Douglas S Poole (++) Jane Marie Hill, Little Gransden, Nr.Sandy, Beds, SG19 3DP HIPWELL Hill Farm, 8 Main Road, Jennifer L Jefferies (+) Mark A Barlow (++) Oliver Daniel Little Gransden, Sandy, Beds, SG19 3DN JEFFERIES Ash Tree Cottage, Jennifer L Jefferies (+) Laura J White (++) John Robert Fuller's Hill, Lt Gransden, SG19 3BP MURDEN 40, Primrose Hill, Little John H Gillett (+) Laura J White (++) Robert James Gransden, Nr Sandy, Beds, SG19 3DP SEABRIGHT The Old Rectory, Little Anthony R W Sargeant Jane S.K. Holland (++) Victoria Gransden, Sandy, (+) Beds, SG19 3DU WHITE 17 Primrose Hill, Little Jane S.K. Holland (+) Anthony R W Sargeant Laura Jayne Gransden, Sandy, (++) SG19 3DP 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled to vote thereat Little Gransden Village Hall, Primrose Hill, Little Gransden, 19 XG1-1 to XG1-238 Sandy 5. -

Newton Parish Council

5 NEWTON PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON 18TH SEPTEMBER 2019 IN NEWTON VILLAGE HALL AT 7.30 PM PRESENT:Councillors L Peden (Chairman)(LP), B Belson (BB), C Eggleton (CE), C Bradbury (CB), P Topping (PT) Mark Deas (Cambridgeshire ACRE) Uzma Ali (South Cambridgeshire District Council) Sally Walmesley (Clerk) Members of the public: 8 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE,DECLARATIONS UNDER THE CODE OF CONDUCT AND REQUESTS FOR DISPENSATIONS All Parish Councillors were in attendance. There were no interests declared. 2. PUBLIC QUESTIONS ON AGENDA ITEMS AND DISCUSSION AT FUTURE MEETINGS (PARISH COUNCIL) 2.1 Housing Needs Survey -Presentation Mark Dees (Cambridgeshire ACRE) The Chairman invited Mr Dees to update attendees on the recent Housing Needs Survey. He introduced himself stating that the last survey had taken place in 2013 and there were various issues at the time and a site was not agreed. A new site had now been identified in the village and Cambridgeshire Housing Society wanted to take the project forward to provide affordable housing for local people. Mr Dees advised on other sites in the District where 350 affordable homes had been built in the past seven years. Newton was a relatively small village with around 170 homes. It was designated a rural area, and infill only village, so any affordable homes would be protected in perpetuity. He added that priority would be given to people from the community. Mr Dees then reported on the process for the survey adding that there had been a 35% return rate which he felt was good. -

Office Address Details.Pdf

Area Name Identifier Office Name Enquiry office no. Office Type Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Address Line 4 Postcode Midlands 2244 ABBERLEY SPDO 01299 896000 SPDO Abberley Delivery Office The Common Worcester WR6 6AY London 1116 ABBEY WOOD SDO 08456 112439 PDO Abbey Wood & Thamesmead Delivery Office Nathan Way London SE28 0AW Wales 871 ABERCARN DO 01495 245025 PDO Abercarn Delivery Office Prince Of Wales Industrial Estate Newport NP11 4AA Wales 236 ABERDARE DO 01685 872007 PDO Aberdare Delivery Office Aberaman Industrial Estate Aberdare CF446ZZ Scotland 985 ABERFELDY SPDO 01887 822835 SPDO Aberfeldy Delivery Office Dunkeld Street Aberfeldy PH152AA Scotland 1785 ABERFOYLE SPDO 01877 382231 SPDO Aberfoyle Delivery Office Main Street Stirling FK8 3UG Wales 880 ABERGAVENNY DO 01873 303500 PDO Abergavenny Delivery Office 1 St. Johns Square Abergavenny NP7 5AZ Scotland 12 ABERLOUR SPDO Wayside Aberlour Delivery Office Elchies Road Aberlour AB38 9AA Wales 874 ABERTILLERY DO 01495 212546 PDO Abertillery Delivery Office Unit 5 Cwmtillery Industrial Estate Abertillery NP131XE Wales 1257 ABERYSTWYTH DO 01970 632600 PDO Glanyrafon Industrial Estate Llanbadarn Fawr Aberystwyth SY23 3GX Thames Valley 934 ABINGDON DO 08456-113-218 PDO Abingdon Delivery Office Ock Street Abingdon OX14 5AD Scotland 8 ABOYNE SPDO 08457740740 SPDO Aboyne Delivery Office Charlestown Road Aboyne AB345EJ North West England 71 ACCRINGTON DO 08456-113-070 PDO Accrington Delivery Office Infant Street Accrington BB5 1ED Scotland 995 ACHARACLE SPDO 01967 431220 SPDO Acharacle -

1 High Meadow, Harston, Cambridge, CB22 7TR Guide

1 High Meadow, Harston, Cambridge, CB22 7TR Guide Price £950,000 Freehold rah.co.uk 01223 800860 A SPACIOUS, FIVE BEDROOM DETACHED FAMILY HOME, OF ABOUT 2800 SQ FT, SITUATED IN THIS PEACEFUL CUL-DE-SAC, WITHIN EASY REACH OF CAMBRIDGE CITY, ADDENBROOKE’S HOSPITAL AND THE M11 5 bedrooms • 2 en suites • family bathroom • ground floor shower room • kitchen/breakfast room • utility room • sitting room • dining room • living room • conservatory • study • reception hall • double glazing • gas fired central heating • rear garden • driveway parking • garage • no upward chain LOCATION Harston is an attractive village about 4 miles south of Cambridge within 1 mile of junction 11 of the M11. A primary school, village hall, post office and village store serve the area which is surrounded by open countryside over which there are many interesting walks. Good rail links are available from nearby Foxton (2 miles away), Great Shelford (5 miles) and Royston (9 miles) which has a fast service to London Kings Cross in only 39 minutes. THE PROPERTY This exceptionally well proportioned family home has been very well maintained and has practical accommodation with a good degree of natural light throughout. The reception hall has attractive Travertine stone flooring and leads to the principal reception rooms. The sitting room is bay fronted, with a dual aspect, including patio doors opening to the rear garden and of particular note is the recessed remote- controlled gas fire surrounded by attractive marble tiling. A living room with Travertine Stone flooring provides further reception space and in turn leads to the purpose-built study. -

South Cambridgeshire District Council – Harston & Comberton Ward

South Cambridgeshire District Council – Harston & Comberton Ward Report to Hauxton Parish Council November 2020 Covid 19 The council will soon be working with other councils to operate a local system of test and trace. Details are still being worked up but it should go 'live' later this month and Environmental Health officers will be working within a rota with officers from the other authorities in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. The decision by the government not to extend free school meals outside of term to eligible children has prompted a number of initiatives in the district, both raising money and donating meals. In case the government’s position on this remain unchanged, SCDC is in talks with the County Council and other District Councils with a view to providing more support for hungry children during the Christmas break. During the lockdown earlier in the year, people were less inclined to contact their GP with non-Covid matters and hospitals prepared for the expected rise in Covid patients by emptying their wards to make space. A side-effect of this has been a rise is the number of people needing treatment now for acute illnesses. Local hospitals report that, as a result, they are nearly at capacity treating patients who are too ill to be discharged as well as having to treat a rising number of severe cases of Covid-19. Since they will be unable to empty their wards as they did in the spring, if Covid case numbers rise significantly as expected. This has been a major driver for the second lockdown. -

18 Button End, Harston, Cambridge, Guide Price £335,000 Freehold 18 Button End, Harston, Cambridge, CB22 7NX

18 Button End, Harston, Cambridge, Guide Price £335,000 Freehold 18 Button End, Harston, Cambridge, CB22 7NX Key Features Guide Price £335,000 - £350,000 170ft rear garden (approx.) Sought after South Cambridgeshire village Potential for extension (STPP) Three bedroom home Guide Price £335,000 - £350,000. A three bedroom semi detached home offering fantastic potential for extension (STPP). The accommodation comprises, entrance hall, lounge, conservatory, kitchen, side entrance, shower room, landing and three bedrooms. Situated in a highly sought after South Cambridgeshire village offering easy access to the surrounding amenities. Harston benefits from a local primary school, a restaurant, doctors surgery with dispensary, an excellent local shop with Post Office counter, village hall and a large recreation ground with a recently improved children's playground. Located within 2 miles is Foxton's mainline railway station to Cambridge (c. 13 minutes) and London Kings Cross (less than 1 hour). Council tax band C. The front of the property has a lawn area with a pathway leading to the entrance door and gated side access. The 170ft rear garden is mainly laid to lawn with a range of mature shrubs and a greenhouse. Ground Floor Kitchen Shower Room 11' 7" x 7' 7" (3.53m Window to the Entrance Hall x 2.31m) side aspect, suite Entrance door, under Window to the rear comprising: walk stairs cupboard, aspect, matching in shower, low open to. eye and base level level wc, vanity Lounge units, inset stainless unit, part tiled 15' 6" x 10' 9" (4.72m steel sink and walls, tiled floor.