Red Band Needle Blight of Pine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinus Nigra V

Technical guidelines for genetic conservation and use European black pine Pinus nigra V. Isajev1, B. Fady2, H. Semerci3 and V. Andonovski4 1 Forestry Faculty of Belgrade University, Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro EUFORGEN 2 INRA, Mediterranean Forest Research Unit, Avignon, France 3 Forest Tree Seeds&Tree Breeding Research Directorate, Ankara,Turkey 4 Faculty of Forestry, Skopje, Macedonia FYR These Technical Guidelines are intended to assist those who cherish the valuable European black pine genepool and its inheritance, through conserving valuable seed sources or use in practical forestry. The focus is on conserving the genetic diversity of the species at the European scale. The recommendations provided in this module should be regarded as a commonly agreed basis to be complemented and further developed in local, national or regional conditions. The Guidelines are based on the available knowledge of the species and on widely accepted methods for the conservation of forest genetic resources. Biology and ecology although seed yield is abundant only every 2–4 years. Trees reach sexual maturity at 15–20 years in The European black pine (Pinus their natural habitat. Flowers nigra Arnold) grows up to 30 appear in May. Female inflores- (rarely 40–50) m tall, with a trunk cences are reddish, and male that is usually straight. The bark catkins are yellow. Fecundation is light grey to dark grey-brown, occurs 13 months after pollina- deeply furrowed longitudinally on tion. Cones are sessile and hori- older trees. The crown is broadly zontally spreading, 4–8 cm long, conical on young trees, umbrel- 2–4 cm wide, yellow-brown or la-shaped on older trees, light yellow and glossy. -

EVERGREEN TREES for NEBRASKA Justin Evertson & Bob Henrickson

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS EVERGREEN TREES FOR NEBRASKA Justin Evertson & Bob Henrickson. For more plant information, visit plantnebraska.org or retreenbraska.unl.edu Throughout much of the Great Plains, just a handful of species make up the majority of evergreens being planted. This makes them extremely vulnerable to challenges brought on by insects, extremes of weather, and diseases. Utilizing a variety of evergreen species results in a more diverse and resilient landscape that is more likely to survive whatever challenges come along. Geographic Adaptability: An E indicates plants suitable primarily to the Eastern half of the state while a W indicates plants that prefer the more arid environment of western Nebraska. All others are considered to be adaptable to most of Nebraska. Size Range: Expected average mature height x spread for Nebraska. Common & Proven Evergreen Trees 1. Arborvitae, Eastern ‐ Thuja occidentalis (E; narrow habit; vertically layered foliage; can be prone to ice storm damage; 20‐25’x 5‐15’; cultivars include ‘Techny’ and ‘Hetz Wintergreen’) 2. Arborvitae, Western ‐ Thuja plicata (E; similar to eastern Arborvitae but not as hardy; 25‐40’x 10‐20; ‘Green Giant’ is a common, fast growing hybrid growing to 60’ tall) 3. Douglasfir (Rocky Mountain) ‐ Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca (soft blue‐green needles; cones have distinctive turkey‐foot bract; graceful habit; avoid open sites; 50’x 30’) 4. Fir, Balsam ‐ Abies balsamea (E; narrow habit; balsam fragrance; avoid open, windswept sites; 45’x 20’) 5. Fir, Canaan ‐ Abies balsamea var. phanerolepis (E; similar to balsam fir; common Christmas tree; becoming popular as a landscape tree; very graceful; 45’x 20’) 6. -

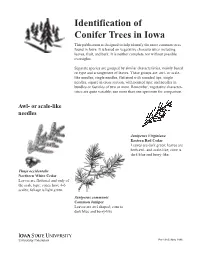

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Thetford Area Hereward Way P 2 Santon House Little Ouse River

Norfolk health, heritage and biodiversity walks Blood Hill 3 Tumulus Walks in and around the Thetford area Hereward Way P 2 Santon House Little Ouse River Norfolk County Council at your service Contents folk or W N N a o r f o l l k k C o u s n t y C o u n c y i it l – rs H ve e di alth io Introduction page 2 • Heritage • B Walk 1 Thetford Castle Hill page 6 Walk 2 Thetford Haling Path page 10 Walk 3 Thetford Abbeygate page 14 Walk 4 Thetford Spring Walk page 18 Walk 5 Thetford BTO Nunnery Lakes Walk page 22 Walks 6 and 7 Great Hockham Woods page 28 Walks 8, 9 and 10 Santon Downham page 32 Walks 11 and 12 Lynford Stag Walks page 38 Walk 13 Rishbeth Wood page 42 Walks locations page 46 Useful contacts page 47 Project information page 48 •Song thrush Photograph by John Harding 1 Introduction ontact with natural surroundings offers a restorative enhance and restore the County’s biological diversity. On these walks you C environment which enables you to relax, unwind and recharge your will be able to see many aspects of the rich and varied biodiversity Norfolk batteries, helping to enhance your mood and reduce your stress levels. has to offer. More details can be found at www.norfolkbiodiversity.org To discover more about the Brecks, visit the website www.brecks.org Regular exercise can help to prevent major conditions, such as coronary heart disease, type II diabetes, high blood pressure, strokes, obesity, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, bowel cancer and back pain. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

The Genetic Structure of the European Black Pine (Pinus Nigra Arnold) Is Shaped by Its Recent Holocene Demographic History

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/535591; this version posted January 30, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The genetic structure of the European black pine (Pinus nigra Arnold) is shaped by its recent Holocene demographic history. Authors: Guia Giovannelli1,2*, Caroline Scotti-Saintagne1*, Ivan Scotti1, Anne Roig1, Ilaria Spanu3, 5 Giovanni Giuseppe Vendramin3, Frédéric Guibal2, Bruno Fady1** 1: INRA, UR629, Ecologie des Forêts Méditerranéennes (URFM), Domaine Saint Paul, 84914 Avignon, France 10 2: Aix-Marseille Université, IMBE, Avenue Louis Philibert, Aix-en-Provence, France 3: Institute of Biosciences and BioResources, National Research Council (CNR), Via Madonna del Piano 10, 50019 Sesto Fiorentino (FI), Italy *: Guia Giovannelli and Caroline Scotti-Saintagne contributed equally to this work 15 **: author for correspondence: bruno.fady(at)inra.fr Highlights • The European black pine, Pinus nigra (Arnold), has a weak spatial genetic structure. • Gene flow among populations is frequent and populations are often of admixed origin. 20 • Current genealogies result from recent, late Pleistocene or Holocene events. • Seven modern genetic lineages emerged from divergence and demographic contractions. • These seven lineages warrant a revision of subspecies taxonomic nomenclature. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/535591; this version posted January 30, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 25 Abstract Fragmentation acting over geological times confers wide, biogeographical scale, genetic diversity patterns to species, through demographic and natural selection processes. -

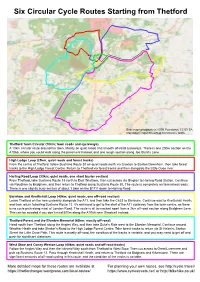

Six Circular Cycle Routes Starting from Thetford

Six Circular Cycle Routes Starting from Thetford Base map cartography (c) OSM Foundation, CC BY-SA. Map data (c) OpenStreetMap Contributors, ODbL. Thetford Town Circular (10km; town roads and cycleways) A 10km circular route around the town. Mostly on quiet roads and smooth off-road cycleways. There is one 200m section on the A1066, where you could walk along the pavement instead, and one rough section along Joe Blunt’s Lane. High Lodge Loop (25km; quiet roads and forest tracks) From the centre of Thetford, follow Sustrans Route 30 on quiet roads north via Croxton to Santon Downham, then take forest tracks to the High Lodge Forest Centre. Return to Thetford via forest tracks and then alongside the Little Ouse river. Harling Road Loop (33km; quiet roads, one short busier section) From Thetford, take Sustrans Route 13 north to East Wrethem, then cut across via Illington to Harling Road Station. Continue via Roudham to Bridgham, and then return to Thetford along Sustrans Route 30. The route is completely on tarmacked roads. There is one slightly busy section of about 1.5km on the B1111 down to Harling Road. Barnham and Knettishall Loop (40km; quiet roads, one off-road section) Leave Thetford on the new cycleway alongside the A11, and then take the C633 to Barnham. Continue east to Knettishall Heath, and then return following Sustrans Route 13. It’s awkward to get to the start of the A11 cycleway from the town centre, as there is no cycle path along most of London Road. The route is all tarmacked apart from a 2km off-road section along Bridgham Lane. -

Breckland Warrens

The INTERNAL ARCHAEOLOGY of the BRECKLAND WARRENS A Report by The Breckland Society © Text, layout and use of all images in this publication: The Breckland Society 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder. Text written by Anne Mason with James Parry. Editing by Liz Dittner. Front cover: Drawing of Thetford Warren Lodge by Thomas Martin, 1740 © Thetford Ancient House Museum, Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service. Dr William Stukeley had travelled through the Brecks earlier that century and in his Itinerarium Curiosum of 1724 wrote of “An ocean of sand, scarce a tree to be seen for miles or a house, except a warrener’s here and there.” Designed by Duncan McLintock. Printed by SPC Printers Ltd, Thetford. The INTERNAL ARCHAEOLOGY of the BRECKLAND WARRENS A Report by The Breckland Society 2017 1842 map of Beachamwell Warren. © Norfolk Record Office. THE INTERNAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE BRECKLAND WARRENS Contents Introduction . 4 1. Context and Background . 7 2. Warren Banks and Enclosures . 10 3. Sites of the Warren Lodges . 24 4. The Social History of the Warrens and Warreners . 29 Appendix: Reed Fen Lodge, a ‘new’ lodge site . 35 Bibliography and credits . 39 There is none who deeme their houses well-seated who have nott to the same belonging a commonwalth of coneys, nor can he be deemed a good housekeeper that hath nott a plenty of these at all times to furnish his table. -

Kings Forest Design Plan

EaEastEEastastst EnglandEngland KinKingsgsKings Thetford Forest Forest Plan 20162016 ——— 202620262026 KKingsings Forest Plan Page 2 Contents Contents ........................................................................... 2 1. What are Forest Plans? ................................................... 3 2. Standard Practices and Guidance ..................................... 4 3. Introduction .................................................................... 5 4. Design Brief and analysis map .......................................... 6 5. Nature ............................................................................. 8 6. People ........................................................................ .. 11 7. Economy ........................................................................ 12 8. Plan Maps & Appraisal .................................................... 13 9. Summary of Proposals ................................................... 17 10. Glossary of Terms .......................................................... 18 11. Management Prescriptions………………………………………...20 12. Tolerance Table………………………………………………………..21 13. Appendices……………………………………………………………...22 Protecting And Expanding England’s forests And woodlands, and increasing their value to society and the environment. Page 3 KKingsings Forest Plan 1. What are Forest Plans? Forest Plans are produced by us, the Forestry Commission (FC), as a means of communi- cating our management intentions to a range of stakeholders. They aim to fulfil a number of objectives: • -

High Lodge and Elveden FP 2015.Pdf

~ Forestry Commission EAST ENGLAND England HIGH LODGE THETFORD FOREST FOREST PLAN 2015-2025 . HIGH LODGE FOREST PLAN PAGE 2. Contents Contents 2 1. What are Forest Plans? 3 2. Standard Practices and Guidance 4 3. Introduction 5 4. Design Brief.I 1. I •• I •• 11.1 ••••• 1 ••••••••••• 1 ••••••• 1••••• 1 •• 1 •• 1 •••• 6 S. Natural and Historic Environment 8 6. Communities and Places ........................•....................... 10 7. Working Woodlands 11 8. Maps It Plan Appraisal ..........................•......................... 12 Forestry Commission 9. Summary of Proposals 17 England 10. Glossary of Terms 18 11. Management Prescriptions 20 12. Tolerance Table 21 13. Appendix A Scheduled Monument Plans 22 PROTECTING AND EXPANDING ENGLAND'S FORESTS AND WOODLANDS, AND INCREASING THEIR VALUE TO SOCIETY Forestry Commission AND THE ENVIRONMENT. woodlands have been certified in IJFSC accordance with the www.fsc.org rules of the Forest PeFC/1S·4(HOOI FSC' C011771 Stewardship Council. Promoting Sustainable Forest ~anagem8nt The mark of responsible forestry www.pefc.org PAaE3 HIGH LODGE FOREST PLAN 1. What are Forest Plans? Forest Plansare produced by us, the Forestry Commission (FC), as a means of communicating our management intentions to a range of stakeholders. They aim to fulfil a number of objectives: To provide descriptions of our woodlands to show what they are like now. To explain the process we go through in deciding what is best for the wood• lands' long term future. To show what we intend the woodlands to look like in the future. To outline our management proposals, in detail, for the first ten years so we can seek approval from the statutory regulators. -

9530 (Sub-) Mediterranean Pine Forests with Endemic Black Pines

Technical Report 2008 24/24 MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 habitats * (Sub-) Mediterranean pine forests with endemic black pines 9530 Directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora The European Commission (DG ENV B2) commissioned the Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 9530 *(Sub)-Mediterranean pine forests with endemic black pines This document was completed in March 2008 by Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente Comments, data or general information were generously provided by: Barbara Calaciura, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Oliviero Spinelli, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Miren del Río, CIFOR-INIA, Spain David García Calvo, Atecma, Spain Piero Susmel, Università di Udine, Italy Stefano Filacorda, Università di Udine, Italy Coordination: Concha Olmeda, ATECMA & Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente ©2008 European Communities ISBN 978-92-79-08333-4 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Zaghi D. 2008. Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 9530 *(Sub)-Mediterranean pine forests with endemic black pines. European Commission This document, which has been prepared in the framework of a service contract (7030302/2006/453813/MAR/B2 "Natura 2000 preparatory actions: Management Models for Natura 2000 Sites”), is not legally binding. Contract realized by: ATECMA S.L. (Spain), COMUNITÀ AMBIENTE (Italy), DAPHNE (Slovakia), ECOSYSTEMS (Belgium), ECOSPHÈRE (France) and MK NATUR- OCH MILJÖKONSULT HB (Sweden). Contents Summary..................................................................................................................................................... -

Thetford Forest Thetford Forest

EEastEastast EnglandEngland HOCKHAM Thetford Forest Forest Plan 2016 ——— 202620262026 Hockham Forest Plan Page 2 Contents Contents ........................................................................... 2 1. What are Forest Plans? ................................................... 3 2. Standard Practices and Guidance ..................................... 4 3. Introduction .................................................................... 5 4. Design Brief and analysis map .......................................... 6 5. Nature ............................................................................. 8 6. People ........................................................................ .. 11 7. Economy ........................................................................ 12 8. Plan Maps & Appraisal .................................................... 13 9. Summary of Proposals ................................................... 18 10. Glossary of Terms .......................................................... 19 11. Management Prescriptions………………………………………...21 12. Tolerance Table………………………………………………………..22 Protecting And Expanding England’s forests And woodlands, and increasing their value to society and the environment. Page 3 Hockham Forest Plan 1. What are Forest Plans? FForest Plans are produced by us, the Forestry Commission (FC), as a means of communi- cating our management intentions to a range of stakeholders. They aim to fulfil a number of objectives: • To provide descriptions of our woodlands to show what they are like