Breckland Warrens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Tax Rates 2020 - 2021

BRECKLAND COUNCIL NOTICE OF SETTING OF COUNCIL TAX Notice is hereby given that on the twenty seventh day of February 2020 Breckland Council, in accordance with Section 30 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992, approved and duly set for the financial year beginning 1st April 2020 and ending on 31st March 2021 the amounts as set out below as the amount of Council Tax for each category of dwelling in the parts of its area listed below. The amounts below for each parish will be the Council Tax payable for the forthcoming year. COUNCIL TAX RATES 2020 - 2021 A B C D E F G H A B C D E F G H NORFOLK COUNTY 944.34 1101.73 1259.12 1416.51 1731.29 2046.07 2360.85 2833.02 KENNINGHALL 1194.35 1393.40 1592.46 1791.52 2189.63 2587.75 2985.86 3583.04 NORFOLK POLICE & LEXHAM 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 175.38 204.61 233.84 263.07 321.53 379.99 438.45 526.14 CRIME COMMISSIONER BRECKLAND 62.52 72.94 83.36 93.78 114.62 135.46 156.30 187.56 LITCHAM 1214.50 1416.91 1619.33 1821.75 2226.58 2631.41 3036.25 3643.49 LONGHAM 1229.13 1433.99 1638.84 1843.70 2253.41 2663.12 3072.83 3687.40 ASHILL 1212.28 1414.33 1616.37 1818.42 2222.51 2626.61 3030.70 3636.84 LOPHAM NORTH 1192.57 1391.33 1590.09 1788.85 2186.37 2583.90 2981.42 3577.70 ATTLEBOROUGH 1284.23 1498.27 1712.31 1926.35 2354.42 2782.50 3210.58 3852.69 LOPHAM SOUTH 1197.11 1396.63 1596.15 1795.67 2194.71 2593.74 2992.78 3591.34 BANHAM 1204.41 1405.14 1605.87 1806.61 2208.08 2609.55 3011.01 3613.22 LYNFORD 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 -

Little Ouse and Waveney Project

Transnational Ecological Network (TEN3) Mott MacDonald Norfolk County Council Transnational Ecological Network (TEN3) Little Ouse and Waveney Project May 2006 214980-UA02/01/B - 12th May 2006 Transnational Ecological Network (TEN3) Mott MacDonald Norfolk County Council Transnational Ecological Network (TEN3) Little Ouse and Waveney Project Issue and Revision Record Rev Date Originator Checker Approver Description 13 th Jan J. For January TEN A E. Lunt 2006 Purseglove workshop 24 th May E. Lunt J. B Draft for Comment 2006 Purseglove This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any o ther project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Mott MacDonald being obtained. Mott MacDonald accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequence of this document being used for a pur pose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person using or relying on the document for such other purpose agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm his agreement to indemnify Mott MacDonald for all loss or damage re sulting therefrom. Mott MacDonald accepts no responsibility or liability for this document to any party other than the person by whom it was commissioned. To the extent that this report is based on information supplied by other parties, Mott MacDonald accepts no liability for any loss or damage suffered by the client, whether contractual or tortious, stemming from any conclusions based on data supplied by parties other than Mott MacDonald and used by Mott MacDonald in preparing this report. -

The Chronology and Context of Flint Mining at Grime's Graves, Norfolk

This article has been published in a revised form in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2018.14. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © The Prehistoric Society 2018. When and Why? The Chronology and Context of Flint Mining at Grime’s Graves, Norfolk, England Frances Healy, Peter Marshall, Alex Bayliss, Gordon Cook, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Johannes van der Plicht and Elaine Dunbar Abstract New radiocarbon dating and chronological modelling have refined understanding of the character and circumstances of flint mining at Grime’s Graves through time. The deepest, most complex galleried shafts were worked probably from the 3rd quarter of the 27th century cal BC and are amongst the earliest on the site. Their use ended in the decades around 2400 cal BC, although the use of simple, shallow, pits in the west of the site continued for perhaps another three centuries. The final use of galleried shafts coincides with the first evidence of Beaker pottery and copper metallurgy in Britain. After a gap of around half a millennium, flint mining at Grime’s Graves briefly resumed, probably from the middle of the 16th century cal BC to the middle of the 15th. These ‘primitive’ pits, as they were termed in the inter-war period, were worked using bone tools that can be paralleled in Early Bronze Age copper mines. Finally, the scale and intensity of Middle Bronze Age middening on the site is revealed, as it occurred over a period of probably no more than a few decades in the 14th century cal BC. -

Role Description LVNB Team Vicar 50% Fte 2019

Role description signed off by: Archdeacon of Sudbury Date: April 2019 To be reviewed 6 months after commencement of the appointment, and at each Ministerial Development Review, alongside the setting of objectives. 1 Details of post Role title Team Vicar 50% fte, held in plurality with Priest in Charge 50% fte Barrow Benefice Name of benefices Lark Valley & North Bury Team (LVNB) Deanery Thingoe Archdeaconry Sudbury Initial point of contact on terms of Archdeacon of Sudbury service 2 Role purpose General To share with the Bishop and the Team Rector both in the cure of souls and in responsibility, under God, for growing the Kingdom. To ensure that the church communities in the benefice flourish and engage positively with ‘Growing in God’ and the Diocesan Vision and Strategy. To work having regard to the calling and responsibilities of the clergy as described in the Canons, the Ordinal, the Code of Professional Conduct for the Clergy and other relevant legislation. To collaborate within the deanery both in current mission and ministry and, through the deanery plan, in such reshaping of ministry as resources and opportunities may require. To attend Deanery Chapter and Deanery Synod and to play a full part in the wider life of the deanery. To work with the ordained and lay colleagues as set out in their individual role descriptions and work agreements, and to ensure that, where relevant, they have working agreements which are reviewed. This involves discerning and developing the gifts and ministries of all members of the congregations. To work with the PCCs towards the development of the local church as described in the benefice profile, and to review those needs with them. -

Thetford Area Hereward Way P 2 Santon House Little Ouse River

Norfolk health, heritage and biodiversity walks Blood Hill 3 Tumulus Walks in and around the Thetford area Hereward Way P 2 Santon House Little Ouse River Norfolk County Council at your service Contents folk or W N N a o r f o l l k k C o u s n t y C o u n c y i it l – rs H ve e di alth io Introduction page 2 • Heritage • B Walk 1 Thetford Castle Hill page 6 Walk 2 Thetford Haling Path page 10 Walk 3 Thetford Abbeygate page 14 Walk 4 Thetford Spring Walk page 18 Walk 5 Thetford BTO Nunnery Lakes Walk page 22 Walks 6 and 7 Great Hockham Woods page 28 Walks 8, 9 and 10 Santon Downham page 32 Walks 11 and 12 Lynford Stag Walks page 38 Walk 13 Rishbeth Wood page 42 Walks locations page 46 Useful contacts page 47 Project information page 48 •Song thrush Photograph by John Harding 1 Introduction ontact with natural surroundings offers a restorative enhance and restore the County’s biological diversity. On these walks you C environment which enables you to relax, unwind and recharge your will be able to see many aspects of the rich and varied biodiversity Norfolk batteries, helping to enhance your mood and reduce your stress levels. has to offer. More details can be found at www.norfolkbiodiversity.org To discover more about the Brecks, visit the website www.brecks.org Regular exercise can help to prevent major conditions, such as coronary heart disease, type II diabetes, high blood pressure, strokes, obesity, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, bowel cancer and back pain. -

WSC Planning Decisions 43/19

PLANNING AND REGULATORY SERVICES DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 25/10/2019 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/15/2298/FUL Planning Application - (i) Extension and Village Hall DECISION: alterations to Hopton Village Hall (ii) Thelnetham Road Approve Application Doctor's surgery and associated car Hopton DECISION TYPE: parking and the modification of the existing Suffolk Committee vehicular access onto Thelnetham Road IP22 2QY ISSUED DATED: (iii) residential development of 37 24 Oct 2019 dwellings (including 11 affordable housing WARD: Barningham units) and associated public open space PARISH: Hopton Cum including a new village green, Knettishall landscaping,ancillary works and creation of new vehicular access onto Bury Road APPLICANT: Pigeon Investment Management AGENT: Evolution Town Planning LLP - Mr David Barker DC/18/0628/HYB Hybrid Planning Application - 1. Full Former White House Stud, DECISION: Planning Application - (i) Horse racing White Lodge Stables Refuse Application industry facility (including workers Warren Road DECISION TYPE: dwelling) and (ii) new access (following Herringswell Delegated demolition of existing buildings to the CB8 7QP ISSUED DATED: south of the site) 2. Outline Planning 22 Oct 2019 Application (Means of Access to be WARD: Iceni considered) (i) up to 100no. dwellings and PARISH: Herringswell (ii) new access (following demolition of existing buildings to the north of the site and the existing dwelling known as White Lodge Bungalow). APPLICANT: Hill Residential Ltd AGENT: Mrs Meghan Bonner - KWA Architects (Cambridge) Ltd Planning and Regulatory Services, West Suffolk Council, West Suffolk House, Western Way, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP33 3YU DC/19/0235/FUL Planning Application - 2no. -

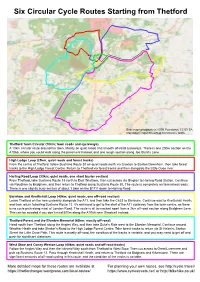

Six Circular Cycle Routes Starting from Thetford

Six Circular Cycle Routes Starting from Thetford Base map cartography (c) OSM Foundation, CC BY-SA. Map data (c) OpenStreetMap Contributors, ODbL. Thetford Town Circular (10km; town roads and cycleways) A 10km circular route around the town. Mostly on quiet roads and smooth off-road cycleways. There is one 200m section on the A1066, where you could walk along the pavement instead, and one rough section along Joe Blunt’s Lane. High Lodge Loop (25km; quiet roads and forest tracks) From the centre of Thetford, follow Sustrans Route 30 on quiet roads north via Croxton to Santon Downham, then take forest tracks to the High Lodge Forest Centre. Return to Thetford via forest tracks and then alongside the Little Ouse river. Harling Road Loop (33km; quiet roads, one short busier section) From Thetford, take Sustrans Route 13 north to East Wrethem, then cut across via Illington to Harling Road Station. Continue via Roudham to Bridgham, and then return to Thetford along Sustrans Route 30. The route is completely on tarmacked roads. There is one slightly busy section of about 1.5km on the B1111 down to Harling Road. Barnham and Knettishall Loop (40km; quiet roads, one off-road section) Leave Thetford on the new cycleway alongside the A11, and then take the C633 to Barnham. Continue east to Knettishall Heath, and then return following Sustrans Route 13. It’s awkward to get to the start of the A11 cycleway from the town centre, as there is no cycle path along most of London Road. The route is all tarmacked apart from a 2km off-road section along Bridgham Lane. -

Breckland Local Plan Consultation Statement 1

Region 1. Introduction 2 2. Issues and Options 3 3. Preferred Directions 5 4. Proposed Sites and Settlement 7 Boundaries 5. General and Specific Consultees 9 6. Conformity with the Statement of 16 Community Involvement Breckland Local Plan Consultation Statement 1 1 Introduction 1.1 This statement of consultation will be submitted to the Secretary of State as part of the examination of the Breckland Local Plan. The statement sets out the information required under Regulation 22 (c) of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012. This statement shows: Who was consulted; How they have been consulted; A summary of the issues raised How issues have been addressed within the Local Plan. 1.2 The 2012 Local Planning Regulations sets out the stages of consultation that a Local Plan is required to go through prior to its submission to the Secretary of State. These are: Regulation 18: a consultation whereby the local authority notifies of their intention to prepare a Local Plan and representations are invited about what the Local Plan should contain Regulation 19: prior to submitting the Local Plan to the Secretary of State, the proposed submission document is made available to the general consultation bodies and the specific consultation bodies. 1.3 In accordance with the regulations and Breckland's Statement of Community Involvement, the Local Plan has been subjected to a number of consultation periods. These are summarised below: Regulation 18: Issues and Options consultation Regulation 18: Preferred Directions consultation Regulation 18: Preferred Sites and Settlement Boundaries consultation 1.4 Full details of each of these consultations is included within this statement. -

Breckland Leaflet

Breckland Full or In Underground Empty? LAND Pink, buff and cream coloured CK with bricks seen in many Breckland B buildings were made from Gault Clay RE from outside the district. This 105 million year old geological deposit also occurs deep under Breckland - this specimen, with a fossil ammonite, came from a water transfer tunnel near Mildenhall. The Devil’s Punchbowl is a large circular basin south of the ‘Drove Road’ in Croxton and has been explained as a solution feature in the Chalk bed-rock. Exploring Breckland Changes of ground water level in the underlying Chalk cause water to rise to give a small lake in the Punchbowl or fall to give dry bed (illustrated). Breckland lies across the western borderlands of Suffolk and Norfolk. Its unique character is defined by its geology as shown by this GeoSuffolk trench on Knettishall Heath Suffolk Wildlife Trust Reserve. The white chalk-rich area in the foreground contrasts with the brown sand in the far end of the trench. These separate soils form large-scale patterned ground, evidence of our periglacial heritage – permanently frozen Discover Answer a sub-soil during the Ice Age. The exact nature of such processes in chalk land continues to Scientific exercise inquisitive minds. Chalk as a Clarke’s Breckland Question Breck district became Breckland in the Naturalists Journal in 1894. Its author was Wm. George Clarke (1877-1925), born in Yorkshire, but of Thetford parents. He married Building Stone Miss Holden of Thetford and he is said to have shaved with a flint implement found near Brandon. -

Kings Forest Design Plan

EaEastEEastastst EnglandEngland KinKingsgsKings Thetford Forest Forest Plan 20162016 ——— 202620262026 KKingsings Forest Plan Page 2 Contents Contents ........................................................................... 2 1. What are Forest Plans? ................................................... 3 2. Standard Practices and Guidance ..................................... 4 3. Introduction .................................................................... 5 4. Design Brief and analysis map .......................................... 6 5. Nature ............................................................................. 8 6. People ........................................................................ .. 11 7. Economy ........................................................................ 12 8. Plan Maps & Appraisal .................................................... 13 9. Summary of Proposals ................................................... 17 10. Glossary of Terms .......................................................... 18 11. Management Prescriptions………………………………………...20 12. Tolerance Table………………………………………………………..21 13. Appendices……………………………………………………………...22 Protecting And Expanding England’s forests And woodlands, and increasing their value to society and the environment. Page 3 KKingsings Forest Plan 1. What are Forest Plans? Forest Plans are produced by us, the Forestry Commission (FC), as a means of communi- cating our management intentions to a range of stakeholders. They aim to fulfil a number of objectives: • -

High Lodge and Elveden FP 2015.Pdf

~ Forestry Commission EAST ENGLAND England HIGH LODGE THETFORD FOREST FOREST PLAN 2015-2025 . HIGH LODGE FOREST PLAN PAGE 2. Contents Contents 2 1. What are Forest Plans? 3 2. Standard Practices and Guidance 4 3. Introduction 5 4. Design Brief.I 1. I •• I •• 11.1 ••••• 1 ••••••••••• 1 ••••••• 1••••• 1 •• 1 •• 1 •••• 6 S. Natural and Historic Environment 8 6. Communities and Places ........................•....................... 10 7. Working Woodlands 11 8. Maps It Plan Appraisal ..........................•......................... 12 Forestry Commission 9. Summary of Proposals 17 England 10. Glossary of Terms 18 11. Management Prescriptions 20 12. Tolerance Table 21 13. Appendix A Scheduled Monument Plans 22 PROTECTING AND EXPANDING ENGLAND'S FORESTS AND WOODLANDS, AND INCREASING THEIR VALUE TO SOCIETY Forestry Commission AND THE ENVIRONMENT. woodlands have been certified in IJFSC accordance with the www.fsc.org rules of the Forest PeFC/1S·4(HOOI FSC' C011771 Stewardship Council. Promoting Sustainable Forest ~anagem8nt The mark of responsible forestry www.pefc.org PAaE3 HIGH LODGE FOREST PLAN 1. What are Forest Plans? Forest Plansare produced by us, the Forestry Commission (FC), as a means of communicating our management intentions to a range of stakeholders. They aim to fulfil a number of objectives: To provide descriptions of our woodlands to show what they are like now. To explain the process we go through in deciding what is best for the wood• lands' long term future. To show what we intend the woodlands to look like in the future. To outline our management proposals, in detail, for the first ten years so we can seek approval from the statutory regulators. -

Thetford Forest Thetford Forest

EEastEastast EnglandEngland HOCKHAM Thetford Forest Forest Plan 2016 ——— 202620262026 Hockham Forest Plan Page 2 Contents Contents ........................................................................... 2 1. What are Forest Plans? ................................................... 3 2. Standard Practices and Guidance ..................................... 4 3. Introduction .................................................................... 5 4. Design Brief and analysis map .......................................... 6 5. Nature ............................................................................. 8 6. People ........................................................................ .. 11 7. Economy ........................................................................ 12 8. Plan Maps & Appraisal .................................................... 13 9. Summary of Proposals ................................................... 18 10. Glossary of Terms .......................................................... 19 11. Management Prescriptions………………………………………...21 12. Tolerance Table………………………………………………………..22 Protecting And Expanding England’s forests And woodlands, and increasing their value to society and the environment. Page 3 Hockham Forest Plan 1. What are Forest Plans? FForest Plans are produced by us, the Forestry Commission (FC), as a means of communi- cating our management intentions to a range of stakeholders. They aim to fulfil a number of objectives: • To provide descriptions of our woodlands to show what they are like