The Aesthetics of Hate Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

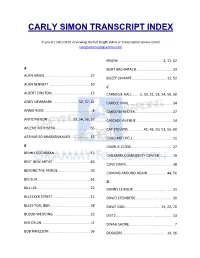

Carly Simon Transcript Index

CARLY SIMON TRANSCRIPT INDEX If you are interested in viewing the full length video or transcription please email [email protected] BRONX ............................................. 3, 11, 52 A BURT BACHARACH .................................... 33 ALAN ARKIN ............................................... 27 BUZZY LINHART ................................... 11, 52 ALAN BENNETT .......................................... 30 C ALBERT EINSTEIN ...................................... 13 CARNEGIE HALL ........ 5, 50, 51, 53, 54, 55, 60 ANDY NEWMARK .......................... 52, 57, 62 CAROLE KING............................................. 34 ANNIE ROSS ................................................. 8 CAROLYN HESTER ...................................... 27 ANTICIPATION ......................... 53, 54, 56, 57 CASCADE AVENUE ..................................... 14 ARLENE ROTHBERG ................................... 55 CAT STEVENS ................42, 43, 50, 53, 55, 60 ARTHUR SCHWARZENHAUER .................... 13 CHAD MITCHELL ........................................ 11 B CHARLIE CLOSE .......................................... 27 BENNY GOODMAN .................................... 13 CHILMARK COMMUNITY CENTER ............. 19 BEST NEW ARTIST ..................................... 60 CLIVE DAVIS ............................................... 38 BEYOND THE FRINGE ................................ 30 COMING AROUND AGAIN ................... 44, 56 BIG SUR ..................................................... 61 D BILL LEE .................................................... -

Mick Evans Song List 1

MICK EVANS SONG LIST 1. 1927 If I could 2. 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Here Without You 3. 4 Non Blondes What’s Going On 4. Abba Dancing Queen 5. AC/DC Shook Me All Night Long Highway to Hell 6. Adel Find Another You 7. Allan Jackson Little Bitty Remember When 8. America Horse with No Name Sister Golden Hair 9. Australian Crawl Boys Light Up Reckless Oh No Not You Again 10. Angels She Keeps No Secrets from You MICK EVANS SONG LIST Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again 11. Avicii Hey Brother 12. Barenaked Ladies It’s All Been Done 13. Beatles Saw Her Standing There Hey Jude 14. Ben Harper Steam My Kisses 15. Bernard Fanning Song Bird 16. Billy Idol Rebel Yell 17. Billy Joel Piano Man 18. Blink 182 Small Things 19. Bob Dylan How Does It Feel 20. Bon Jovi Living on a Prayer Wanted Dead or Alive Always Bead of Roses Blaze of Glory Saturday Night MICK EVANS SONG LIST 21. Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the dark I’m on Fire My Home town The River Streets of Philadelphia 22. Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Heaven Run to You Cuts Like A Knife When You’re Gone 23. Bush Glycerine 24. Carly Simon Your So Vein 25. Cheap Trick The Flame 26. Choir Boys Run to Paradise 27. Cold Chisel Bow River Khe Sanh When the War is Over My Baby Flame Trees MICK EVANS SONG LIST 28. Cold Play Yellow 29. Collective Soul The World I know 30. Concrete Blonde Joey 31. -

ANN HAMPTON CALLAWAY - Biography

ANN HAMPTON CALLAWAY - Biography ANN HAMPTON CALLAWAY is one of the finest singer/songwriters of our generation. The statuesque performer dazzles music lovers as a singer, pianist, composer, lyricist, arranger, actress, and educator. Her talents have made her equally at home in jazz and pop as well as on stage, in the recording studio, on TV and in film. She is best known for starring in the hit Broadway musical "SWING!" and for writing and singing the theme to the internationally successful TV series,” THE NANNY". Ann is a devoted keeper-of-the-flame of the great American songbook. She brings fresh and original interpretations to these timeless classics and works to uphold the canon by writing songs with Cole Porter, Carole King, Barbara Carroll and others. Her spontaneity, intelligence, and soulful charisma have won her a diverse fan-base including notables as Barbra Streisand, Clive Davis, Carly Simon and Wynton Marsalis. The New York Times writes, “For sheer vocal beauty, no contemporary singer matches Ms. Callaway.” Ann attributes her voice and love of music to her mother, Shirley, who throughout her childhood sang and played torch songs, Gershwin and German lieder at the piano. Of the uniquely musical household she says, “I didn’t know it at the time, but we were sort of the Von Trapp family of Chicago.” After a music teacher discovered her unusually mature soprano voice, Ann was encouraged to study classically, honing the pitch-perfect control and expressive three octave range she is known for. While her voice teachers suggested she could have a career in opera, Ann eventually realized that she would be happier singing the music she most loved. -

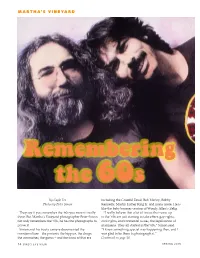

Remembering the 60S

MARTHA’S VINEYARD Remembering the 60s By Gayle Fee including the Grateful Dead, Bob Marley, Bobby Photos by Peter Simon Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. and many more. He is like the baby boomer version of Woody Allen’s Zelig. They say if you remember the ‘60s you weren’t really “I really believe that a lot of issues that came up there. But Martha’s Vineyard photographer Peter Simon not only remembers the ‘60s, he has the photographs to civil rights, environmental issues, the legalization of prove it. marijuana. They all started in the ‘60s,” Simon said. Simon and his trusty camera documented the “I knew something special was happening then, and I counterculture – the protests, the hippies, the drugs, was glad to be there to photograph it.” the communes, the gurus – and the icons of that era Continued on page 16 14 BIRD’S EYE VIEW SPRING 2015 MARTHA’S VINEYARD The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia and Mickey Hart at The Palladium, New York 1977. James Taylor posing for the cover of his 1972 album One Man Dog. “I am a golden god,” proclaims Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant in Los Angeles 1975. SPRING 2015 B I R D’S E Y E V I E W 15 MARTHA’S VINEYARD Simon’s story is a familiar one to those of his Carly Simon and Bob Weir of The Grateful Dead, in New York, 1985. (Below) John Belushi at the Hot Tin Roof on Martha’s and talented family. His father Richard co- Vineyard, 1979. founded the giant publishing house Simon & Schuster. -

1999 Prince (I've Had) the Time of My Life Dirty Dancing 3 A.M

Title 1999 Prince (I've Had) the Time of My Life Dirty Dancing 3 a.m. Matchbox 20 A Lot of Lovin' to Do Charles Strouss Bye, Bye Birdie A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton A Whole New World Aladdin Aladdin A Wonderul Guy Rodgers & Hammerstein South Pacific All I Ask of You Andrew Lloyd Webber Phantom of the Opera Duet Another Suitcase in Another Hall Andrew Lloyd Webber Evita Anthem Chess Chess Anything You Can Do Irving Berlin Annie Get Your Gun Duet Apologize One Republic Bad Michael Jackson Bali Hai Rodgers & Hammerstein South Pacific Barnum (Complete Score) Cy Coleman Barnum Beautiful Christina Aguilera Beauty and the Beast Beauty and the Beast Beauty and the Beast Beauty School Dropout Grease Grease Beethoven Day You're a Good Man Charlie Brown You're a Good Man Charlie Brown Before I Gaze at You Again Lerner & Loewe Camelot Believe Cher Bennie & the Jets Elton John Best of Beyonce (Anthology) Beyonce Better Edward Kleban A Class Act Bewtiched Ella Fitzgerald Pal Joey Beyond the Sea Bobby Darin Black Coffee Ella Fitzgerald Blackbird The Beatles Blue Christmas Elvis Presley Blue Moon Elvis Presley Bohemian Rhapsody Queen Bombshell (music from SMASH) Marc Shaiman Bombshell Born this Way Lady Gaga Bosom Buddies Jerry Herman Mame Duet Both Sides Now Joni Mitchell Brand New You Jason Robert Brown 13, the Musical Breeze Off the River The Full Monty The Full Monty Bring Him Home Boublil & Schoenberg Les Miserables Bring On the Men Leslie Bricusse Jekyll & Hyde Broadway Baby Stephen Sondheim Follies Broadway, Here I Come Smash Smash Brown-Eyed -

Frank Filipetti

JBL.Filipetti.ProSound.0808.qxd 8/1/08 3:12 PM Page 1 FRANK FILIPETTI Five-time GRAMMY® Award-winning engineer, producer whose credits include projects with: 10,000 Maniacs Barbra Streisand Billy Joel Carly Simon Courtney Love Elton John Frank Zappa James Taylor John Waite Kiss Korn Luciano Pavarotti Luther Vandross Mariah Carey Ray Charles Rod Stewart “ When working in a recording environment, I've found it critical to 1.Create an atmosphere that people find comfortable and 2. Make sure the listening environment, especially your speakers, are as good as you can get - so you don't second-guess what you're hearing. When I first used the LSR6300s, I just loved what I was hearing and I've been using them ever since. They’re smooth across the entire spectrum. I don't hear the speaker - just the music. Working in a range of rooms in LA, London, and here in Manhattan, the ability to tune the LSRs to the room is extremely useful. I'm really stoked about the new LSR4300 series especially the 6-inch model. The 4300s, with automated Room Mode Correction, go one step further. I put the supplied calibration mic in the center of the room, push a button and the speaker does all the work. It not only does it, it does it well and it does it right! The technology's amazing - I'm blown away by it. I take my LSRs wherever I go.” Hear why award-winning engineer, producer, Frank Filipetti is blown away by the LSR series studio monitors. -

The James Taylor Encyclopedia

The James Taylor Encyclopedia An unofficial compendium for JT’s biggest fans Joel Risberg GeekTV Press Copyright 2005 by Joel Risberg All rights reserved Published 2005 Printed in the United States of America James Taylor Online www.james-taylor.com [email protected] Cover photo by Joana Franca. This book is not approved or endorsed by James Taylor, his record labels, or his management. For Sandra, who brings me snacks. CONTENTS BIOGRAPHY 1 TIMELINE 16 SONG ORIGINS 27 STUDIO ALBUMS 31 SINGLES 43 WORK ON OTHER ALBUMS 44 OTHER COMPOSITIONS 51 CONCERT VIDEOS 52 SINGLE-SONG MUSIC VIDEOS 57 APPEARANCES IN OTHER VIDEOS 58 MISCELLANEOUS WORK 59 NON-U.S. ALBUMS 60 BOOTLEGS 63 CONCERTS ON TELEVISION 70 RADIO APPEARANCES 74 MAJOR LIVE PERFORMANCES 75 TV APPEARANCES 76 MAJOR ARTICLES AND INTERVIEWS 83 SHEET MUSIC AND MUSIC BOOKS 87 SAMPLE SET LISTS 89 JT’S FAMILY 92 RECORDINGS BY JT ALUMNI 96 POINTERS 100 1971 Time cover story – and nearly every piece of writing about James Taylor since then – characterized the musician Aas a troubled soul and the inevitable product of a family of means that expected quite a lot of its kids. To some extent, it was true. James did find inspiration for much of his life’s work in his emotional torment and the many years he spent fighting drug addiction and depression. And he did hail from an affluent, musically talented family that could afford to send its progeny to exclusive prep schools and expensive private mental hospitals. But now James Taylor in his fifties has the benefit of hindsight to moderate any lingering grudges against a press that persistently pigeonholed him – first as a sort of Kurt Cobain of his day, and much later as a sleepy crooner with his most creative years behind him. -

Yachtly Crue Sample Song List C/O Cleveland Music Group

Yachtly Crue Sample Song List c/o Cleveland Music Group Little River Band ~ Reminiscing Player ~ Baby Come Back Walter Egan ~ Magnet and Steel Robbie Dupree ~ Steal Away Nick Gilder ~ Hot Child in the City Seals and Crofts ~ Summer Breeze Robert John ~ Sad Eyes Ambrosia ~ How Much I Feel 10cc ~ Things We Do For Love England & Dan ~ I’d Really Love to See You Tonight Carly Simon ~ You’re So Vain Pablo Cruise ~ Whatcha Gonna Do? ELO ~ Evil Woman Steely Dan ~ Hey Nineteen Gerry Rafferty ~ Baker Street Looking Glass ~ Brandy Hall & Oates ~ Rich Girl Jay Fergusen ~ Thunder Island Elton John & Kiki Dee ~ Don’t Go Breaking My Heart Orleans ~ Still the One Maxine Nightengale ~ Right Back to Where We Started From Boz Scaggs ~ Lido Shuffle Steely Dan ~ Peg Christopher Cross ~ Ride Like the Wind Leo Sayer ~ You Make Me Feel Like Dancing Rupert Holmes ~ Escape (The Pina Colada Song) Billy Ocean ~ Caribbean Queen Michael McDonald ~ I Keep Forgettin Exile ~ Kiss You All Over Hall & Oates ~ Maneater The Doobie Brothers ~ What a Fool Believes Captain and Tennille ~ Love Will Keep Us Together Jackson Browne ~ Somebody’s Baby Rod Stewart ~ Do Ya Think I’m Sexy? Bob Welch ~ Ebony Eyes Pilot ~ Magic Toto ~ Africa Benny Mardones ~ Into the Night Crosby, Stills & Nash ~ Southern Cross Billy Joel ~ My Life Climax Blues Band ~ Couldn’t Get it Right Phil Collins ~ Easy Lover Styx ~ Come Sail Away Boz Scaggs ~ Lowdown Fleetwood Mac ~ Go Your Own Way Toto ~ Rosanna Kenny Loggins ~ I’m Alright America ~ You Can Do Magic King Harvest ~ Dancing in the Moonlight. -

They're Playing Our Song

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein 2017 Summer Theatre Productions 2011-2020 7-6-2017 They're Playing Our Song Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/summer_production_2017 Part of the Acting Commons, Dance Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department, "They're Playing Our Song" (2017). 2017 Summer Theatre. 2. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/summer_production_2017/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Productions 2011-2020 at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2017 Summer Theatre by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. y V r . EPIC IMAGINATION. INTIMATE ENCOUNTERS. omjm mSBUBS ¥f¥rw.oaklandnur8ery.com Columbus: 1156 Oakland Park Ave. 614-268-351 1 Delaware: 25 Kilbourne Rd. 740-369-5454 Dublin: 4261 W. Dublin-Granville Rd. 614-874-2400 New Albany: 5211 Johnstown Rd. 614-917-1020 mi — f .32 A€res of Gardening Pleasure" ......................... OTTERBEIN SUMMER THEATRE presents Book by NEIL SIMON Music by MARVIN HAMLISCH Lyrics by CAROLE BAYER SAGER Directed by MELISSA LUSHER Musical Direction by Choreography by DENNIS DAVENPORT STELLA HIATT KANE Scenic Design by Costume Design by ROB JOHNSON TATJANA LONGEROT Lighting Design by Sound Design by ANDY BAKER DOC DAVIS Stage Managed by ETHAN WINTGENS July 6-9,13-16, & 20-22, 2017 Riley Auditorium in the Battelle Fine Arts Center 170 W. Park St., Westerville "TheyTe Playing Our Song (Neil Simon/Marvin Hamslich)" is presented by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. -

Monterey String Quartet Classical Songlist

MONTEREY STRING QUARTET CLASSICAL SONGLIST WEDDING / CLASSICAL ROMANTIC CLASSICS "Air on the G String" (Bach) Adagio for Strings (Barber) Allelujah from “Exsultate, Jubilate” (Mozart) Adagio from "Pathétique" Sonata (Beethoven) Ave Maria (Bach/Gounod) Bachianas Brazileiras #5 (Villa-Lobos) Ave Maria (Schubert) Le Canticle de Jean Racine (Fauré) Bridal Chorus “Lohengrin” (Wagner) Clair de Lune (Debussy) Canon in D (Pachelbel) “Elvira Madigan” from Piano Concerto #21 (Mozart) Entrance of the Queen of Sheba (Handel) Etude #3 (Chopin) Hornpipe from “Watermusic” (Handel) Fritz Kreisler Selections Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring (Bach) Für Elise (Beethoven) Lord’s Prayer (Malotte) Girl with the Flaxen Hair (Debussy) Meditation from "Thaïs" (Massenet) Gymnopedies #1,2 & 3 (Satie) Ode to Joy from “9th Symphony” (Beethoven) Hungarian Dances (Brahms) Panis Angelicus (Frank) Largo from the “New World” Symphony (Dvorak) Pie Jesu from “Requiem” (Andrew Lloyd Webber) Lullaby (Gershwin) Prelude from “Te Deum” (Charpentier) Melody from “Dance of the Blessed Spirits” (Gluck) Prince of Denmark March (Clarke) Menuet from “Le Tombeau de Couperin” (Ravel) Promenade “Pictures at an Exhibition”(Moussorgsky) Morning Song from “Peer Gynt Suite” (Grieg) Rondeau from “Fanfares” (Mouret) Pavane (Fauré) Sheep May Safely Graze (Bach) Pavane pour une Infante Defunte (Ravel) Saint Anthony Chorale (Haydn) Rhapsody on Theme of Paganini (Rachmaninov) Trumpet Tune (Clarke) Romance Without Words #3 (Fauré) Trumpet Voluntary (Stanley) Romanza Andaluza (Sarasate) Wedding March -

Yacht Rock Schooner – Song List.Docx.Docx

50 Ways to Leave Your Lover - Paul Simon Africa - Toto Afternoon Delight - Starland Vocal Band All Night Long - Lionel Richie Arthur's Theme (The Best That You Can Do) – Christopher Cross Baby Come Back - Player Baker Street - Gerry Rafferty Biggest Part of Me - Ambrosia Brandy - Looking Glass Couldn't Get It Right - Climax Blues Band Dance With Me - Orleans Diamond Girl - Seals & Crofts Doctor My Eyes - Jackson Browne Escape (The Pina Colada Song) - Rupert Holmes Give Me The Night – George Benson Grease - Frankie Valli Hey Nineteen - Steely Dan Hold the Line - Toto Hot Child in the City - Nick Gilder How Long - Ace I Can't Go for That - Hall & Oates I Keep Forgetting - Michael McDonald I Wanna Kiss You All Over – Exile I'll Be Around – The Spinners I'm Alright - Kenny Loggins Jive Talkin’ - The Bee Gees Just the Two of Us - Bill Withers / Grover Washington Kid Charlemagne – Steely Dan Lido Shuffle - Boz Scaggs Little Jeannie - Elton John Lonely Boy - Andrew Gold Lonesome Loser - Little River Band Lotta Love - Nicolette Larson Love Boat Theme- Jack Jones Lovely Day - Bill Withers Lowdown - Boz Scaggs Minute by Minute - The Doobie Brothers Moonlight - Starbuck More Than a Woman - The Bee Gees My Love is Alive - Gary Wright My Old School – Steely Dan Nights On Broadway - The Bee Gees Peg - Steely Dan Private Eyes - Hall & Oates Reminiscing - Little River Band Rich Girl - Hall & Oates Ride Captain Ride - Blues Image Ride Like the Wind - Christopher Cross Right Down The Line - Gerry Rafferty Rikki Don't Lose That Number - Steely Dan Rosanna -

Who Is "You're So Vain" About? : Reference in Popular Music Lyrics

WHO IS »YOU'RE SO VAIN« ABOUT? REFERENCE IN POPULAR MUSIC LYRICS Theodore Gracyk »But you do speak of understanding music. … The way music speaks. Do not forget that a poem, even though it is composed in the language of information, is not used in the language- game of giving information.« (Ludwig Wittgenstein 1970: 27) »A song is capable of having several life spans.« (Paul Simon, quoted in Alterman 1970: 38) I. Introduction In an iconic scene in the film Say Anything (1989), Lloyd Dobler stands outside the bedroom of his former girlfriend and lofts a large boom box above his head. Inside the house, Diane Court recognizes the song blaring from the boom box: Peter Gabriel's »In Your Eyes«. Lloyd had played the song for her once before, shortly after they started to date. To understand the movie, one must understand this scene. To understand the scene, one must understand the song, »In Your Eyes«. In addition, one must understand what the charac- ter is doing with the (recorded) song. Lloyd is not inviting Diane to engage in disinterested, appreciative engagement of a piece of music. Instead, Lloyd is using the music to communicate something to Diane. There is no question of understanding a communicative action unless there is also a possibility of misunderstanding it. In this sense, »understand- ing« indicates successful interpretation. If someone thinks that Jimi Hendrix's »Purple Haze« is an early anthem of gay liberation, based on mishearing the lyric »'scuse me while I kiss the sky« as »kiss this guy«, then that interpreta- tion of the Hendrix recording is a misunderstanding.