Who Is "You're So Vain" About? : Reference in Popular Music Lyrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook Sulpalco N.32

SUL PALCO QUINDICINALE ONLINE DI ARTE MUSICA SPETTACOLO DI ROMA E NON SOLO … EDIZIONE N. 32 DEL 1 GIUGNO 2012 www.sulpalco.it - [email protected] Edizione N. 32 Del 1 Giugno 2012 ATTACK THE BLOCK – INVASIONE ALIENA ................................................................... 3 I MEN IN BLACK IN BILICO NEL TEMPO ......................................................................... 7 ICE 2020 ...................................................................................................................................... 11 LA FAVOLA DI di W.S. ........................................................................................................... 14 UN APPARTAMENTO IN CITTA’........................................................................................ 21 NEL BEL MEZZO DI UN GELIDO INVERNO .................................................................. 24 MILONGA MERINI ................................................................................................................. 28 CHI ERANO I JOLLY ROCKERS? ........................................................................................ 31 INTERVISTA A FABRIZIO ROMAGNOLI ......................................................................... 34 MARYLIN MANSON TORNA A PICCHIARE ................................................................... 44 FEEZY ......................................................................................................................................... 47 CHEMICAL BROTHERS, MAI SCONTATI ....................................................................... -

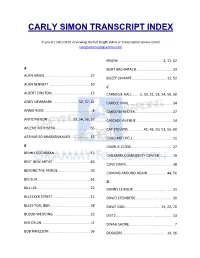

Carly Simon Transcript Index

CARLY SIMON TRANSCRIPT INDEX If you are interested in viewing the full length video or transcription please email [email protected] BRONX ............................................. 3, 11, 52 A BURT BACHARACH .................................... 33 ALAN ARKIN ............................................... 27 BUZZY LINHART ................................... 11, 52 ALAN BENNETT .......................................... 30 C ALBERT EINSTEIN ...................................... 13 CARNEGIE HALL ........ 5, 50, 51, 53, 54, 55, 60 ANDY NEWMARK .......................... 52, 57, 62 CAROLE KING............................................. 34 ANNIE ROSS ................................................. 8 CAROLYN HESTER ...................................... 27 ANTICIPATION ......................... 53, 54, 56, 57 CASCADE AVENUE ..................................... 14 ARLENE ROTHBERG ................................... 55 CAT STEVENS ................42, 43, 50, 53, 55, 60 ARTHUR SCHWARZENHAUER .................... 13 CHAD MITCHELL ........................................ 11 B CHARLIE CLOSE .......................................... 27 BENNY GOODMAN .................................... 13 CHILMARK COMMUNITY CENTER ............. 19 BEST NEW ARTIST ..................................... 60 CLIVE DAVIS ............................................... 38 BEYOND THE FRINGE ................................ 30 COMING AROUND AGAIN ................... 44, 56 BIG SUR ..................................................... 61 D BILL LEE .................................................... -

Integration Des Chaos : Marilyn Manson, Männlichkeit, Lust Und Scheitern L'amour Lalove, Patsy 2017

Repositorium für die Geschlechterforschung Integration des Chaos : Marilyn Manson, Männlichkeit, Lust und Scheitern l'Amour laLove, Patsy 2017 https://doi.org/10.25595/398 Eingereichte Version / submitted version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: l'Amour laLove, Patsy: Integration des Chaos : Marilyn Manson, Männlichkeit, Lust und Scheitern, in: Nagelschmidt, Ilse; Borrego, Britta; Majewski, Daria; König, Lisa (Hrsg.): Geschlechtersemantiken und Passing be- und hinterfragen (Frankfurt am Main: PL Academic Research, 2017), 169-194. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25595/398. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY 4.0 Lizenz (Namensnennung) This document is made available under a CC BY 4.0 License zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden (Attribution). For more information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de www.genderopen.de Integration des Chaos – Marilyn Manson, Männlichkeit, Lust und Scheitern Patsy l'Amour laLove Marilyn Manson as a public figure represents exemplarily aspects of goth subculture: Aspects of life that shall be denied as not belonging to a fulfilled and happy life from a normative point of view are being integrated in a way that is marked by pleasure. Patsy l‘Amour laLove uses psychoanalytic approaches to the integration of chaos, of pain and failure in Manson‘s recent works. „This will hurt you worse than me: I'm weak, seven days a week ...“ Marilyn Manson1 FOTO © by Max Kohr: Marilyn Manson & Rammstein bei der Echo-Verleihung 2012 Für Fabienne. Marilyn Manson verwirft in seinem Werk die Normalität, um sich im gleichen Moment schmerzlich danach zu sehnen und schließlich den Wunsch nach Anpassung wieder wütend und lustvoll zu verwerfen. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

The Aesthetics of Hate Music

The Aesthetics of �Hate Music� By Keith Kahn-Harris Introduction The expression of hatred in music is, for many people, something intrinsically worrisome. From Nazi skinhead music to homophobic reggae, hate music seems to demand close watching at least and direct censorship at most. This is perfectly understandable given contemporary concerns about �hate speech� and in many ways the desire not to let hate-filled music pass without comment is a laudable one. However, I want to argue that the terms of the debate about hate and music are all too frequently rooted in certain, very questionable, ideas about musical aesthetics and that as a consequence some of the complexities surrounding issues regarding hatred and music tend to be ignored. In particular I wish to question the tacit assumption behind much writing on music and hate that it is a prioria problem. That is, that hatred and music simply do not go together and when they do come together the consequences can only be worrying. In fact, this assumption is historically specific and open to question and contestation, with important consequences for our understanding of music and hate The legitimacy of hatred In western societies at least, the development in the nineteenth century of a particular musical aesthetic has had far-reaching consequences (Chanan 1994). That is, the resurrection of the Platonic idea that music should ideally represent a form of transcendental perfection. In an impure world of lust, conflict and hatred, music should ideally represent the world as it ought to be, a world that is whole, perfect, free of messy bodily imperfections and antagonism. -

Mick Evans Song List 1

MICK EVANS SONG LIST 1. 1927 If I could 2. 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Here Without You 3. 4 Non Blondes What’s Going On 4. Abba Dancing Queen 5. AC/DC Shook Me All Night Long Highway to Hell 6. Adel Find Another You 7. Allan Jackson Little Bitty Remember When 8. America Horse with No Name Sister Golden Hair 9. Australian Crawl Boys Light Up Reckless Oh No Not You Again 10. Angels She Keeps No Secrets from You MICK EVANS SONG LIST Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again 11. Avicii Hey Brother 12. Barenaked Ladies It’s All Been Done 13. Beatles Saw Her Standing There Hey Jude 14. Ben Harper Steam My Kisses 15. Bernard Fanning Song Bird 16. Billy Idol Rebel Yell 17. Billy Joel Piano Man 18. Blink 182 Small Things 19. Bob Dylan How Does It Feel 20. Bon Jovi Living on a Prayer Wanted Dead or Alive Always Bead of Roses Blaze of Glory Saturday Night MICK EVANS SONG LIST 21. Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the dark I’m on Fire My Home town The River Streets of Philadelphia 22. Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Heaven Run to You Cuts Like A Knife When You’re Gone 23. Bush Glycerine 24. Carly Simon Your So Vein 25. Cheap Trick The Flame 26. Choir Boys Run to Paradise 27. Cold Chisel Bow River Khe Sanh When the War is Over My Baby Flame Trees MICK EVANS SONG LIST 28. Cold Play Yellow 29. Collective Soul The World I know 30. Concrete Blonde Joey 31. -

An Examination of Halloween Literature and Its Effect on the Horror Genre

An Examination of Halloween Literature And its Effect on the Horror Genre WYLDE, Benjamin Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26103/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26103/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Sheffield Hallam University Faculty of Development and Society An Examination of Halloween Literature And its Effect on the Horror Genre By Benjamin Wylde April 2019 Supervised by: Shelley O’Brien and Dr Ana-Maria Sanchez-Arce A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Master of English by Research Acknowledgements I would like to thank Sheffield Hallam University for allowing me a place on the course and for giving me the opportunity to write about a subject that I am deeply passionate about. I would like to thank Shelley O’Brien, firstly for the care and attention to which she has paid, not only to my work, but also my well-being and for the periods in which she was, by circumstance, forced to conduct periods of supervision alone. I would like to thank my second supervisor Ana-Maria Sanchez- Arce, for her care, duty and attention in helping me to write my work. -

ESNS Confirms First Speakers for 2020 Conference

PRESS RELEASE Groningen, May 22, 2019 ESNS confirms first speakers for 2020 conference ESNS (Eurosonic Noorderslag) has confirmed the first speakers for the ESNS 2020 conference. Cooking Vinyl founder Martin Goldschmidt will be doing a keynote interview in Groningen. Mojo Concerts’ co-director Rob Trommelen is confirmed for a beer crate session, while music business family Barry, Lucy and Jonathan Dickins will share a stage for the first time. The Dickins Dynasty: Barry, Lucy & Jonathan With a family legacy that stretches back to the formation of the NME, the Dickins family are no stranger to the music business. As one of the world's most successful booking agents, Barry Dickins (Neil Young, Bob Dylan, Paul Simon) has co-steered ITB for 40 years, working alongside his daughter Lucy whose roster includes Adele, Mumford & Sons, Hot Chip, Laura Marling and James Blake. Meanwhile, as CEO of September Management, Jonathan's stable includes Adele, Jamie T, London Grammar, Rex Orange County & King Krule. The trio will be interviewed by Greg Parmley (ILMC, IQ). A truly unique session, as this is the first time they've shared the same stage. Keynote Martin Goldschmidt (Cooking Vinyl) Martin Goldschmidt is Managing Director and founder of Cooking Vinyl and Chairman of the Cooking Vinyl Group. Thirty years after its inception in a council flat in Stockwell, Cooking Vinyl remains one of the original and best indie labels in the UK. His current roster includes Nina Nesbitt, Passenger, Fantastic Negrito, Billy Bragg, Lissie, Will Young and Baby Metal. Cooking Vinyl has always been a digital pioneer, being the first UK record label to get content into eMusic. -

27Th April 2018

27th April 2018 The information contained within this announcement is deemed by the Company to constitute inside information stipulated under the Market Abuse Regulation (EU) No. 596/2014. Upon the publication of this announcement via the Regulatory Information Service, this inside information is now considered to be in the public domain. EVR Holdings plc (‘EVR’ or the ‘Company’) EVR Holdings Signs Agreements with Record Labels and Music Publishers EVR Holdings plc (AIM: EVRH), the leading creator of virtual reality music content and its subsidiary MelodyVR Ltd (‘MelodyVR’) are pleased to announce that on 26 April 2018 MelodyVR entered into the following multi-year agreements: 1. Publishing Agreement with Kobalt (Kobalt Music Publishing America, Inc.) and AMRA (American Music Rights Association). Kobalt Music publishing represents the rights of songwriters and artists such as Alt-J, Beck, Fleetwood Mac, Gwen Stefani, Jack Garratt, Lionel Richie, Moby, Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds, Nine Inch Nails, Placebo, Queens Of The Stone Age, Rudimental and many more. 2. Record Label Agreement with Cooking Vinyl (Cooking Vinyl Limited). Cooking Vinyl represents musicians such as Alison Moyet, Goldie, Groove Armada, James, Madness, Marilyn Manson, The Fratellis, The Prodigy, Underworld and many more. 3. Record Label Agreement with Red Bull Records (Red Bull Records Inc.) Red Bull Records represents artists such as AWOLNATION, The Aces, Black & Gold, Beartooth, Five Knives and Itch. 4. Publishing Agreement with AKM (AKM Autoren, Komponisten und Musikverleger) and Austro Mechana. AKM/Austro mechana administers the performance, reproduction and distribution rights in musical works from composers and music publishers in Austria. 5. Record Label agreement with Hospital Records (Hospital Records Limited) and Publishing agreement with Hospital Records (Songs In The Key Of Knife T/A Hospital Records Limited). -

On Marilyn Manson's Album Born Villain Morag Keil Quotes Model

In her text “Eye Contact” on Marilyn Manson’s album Born Villain Morag Keil quotes model and actress Rosie Huntington-Whiteley: “At some point you have to start looking at yourself as a product. You have to do business with yourself. I look at Gisele – she has the character that everyone wants. She has made herself into a brand.” It happens to all of us, maybe even the best of us. This is where this exhibition got its starting point: in the embarrassing moment when we realize that everything we thought was authentic and that we could be proud of also functions by itself as an image – autonomous and elusive, efficient, deceitful. Art, life, work, occupation becoming their own representations in the form of positions, fantasies and identities. Caught up in ambivalent desires or ambitions, this pattern of self-definition and self- awareness can be part of an empowerment process, but also unfold as a marketing strategy, filling in specific demands in terms of social exposure and personal/professional expectations. The practice of an artist is routinely seen as a definition by itself: the embodiment of a lifestyle – the essential post-romantic surplus value. Trouble, annoyance and paradoxes appear here when the conventions of ironic heroization, spleenful projection, or transgression get exhausted. Which is, after all, fine. It’s not the forms and the signs that can stand for an attitude. More so the way they are used, put together and exchanged; activating their potential for meaning and feeling. Do these problems sound too general, or too familiar? Such looming questions seem not to belong to anyone anymore. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

American Film Composer Tyler Bates Has Over 60 Films to His Name and Has Also Just Finished Writing Music for Marilyn Manson's

TAKE YOUR SEATS ‘Killing Strangers’ @YouTube Words: Robyn Morrison Photo: Matt Bishop American film composer Tyler Bates has over 60 films to his name and has also just finished writing music for Marilyn Manson’s The Pale Emperor. He talks to Robyn Morrison about what it’s like to soundtrack people’s lives for a living. yler Bates is a composer in hot demand. He recently Festival tour, Bates spoke about his involvement in the penned the score to the films Guardians Of The Galaxy writing of The Pale Emperor and how he applied his film and John Wick to go with an impressive arsenal of score techniques to this album. previous scores dating back to 1983, and has worked The partnership between Bates and Manson was born Twith Rob Zombie (Dawn Of The Dead, Halloween and when the pair met on the set of popular US TV series Halloween II), Zack Snyder (Sucker Punch and 300) and Matt Californication. Dillon (City Of Ghosts) to name just a few. “The season finale episode culminated in a concert at the More recently, Bates completed work on a soundtrack Greek Theater in Los Angeles for a fictitious rockstar played of a different nature; the ninth studio album from Marilyn by Tim Minchin,” Bates remembers. “They decided to stage Manson, entitled The Pale Emperor. During his visit to a real rock concert, I got to know him and a couple of days Australia as part of Manson’s band for the Soundwave later we played another concert – it was Manson, Steve Jones, 52 Tim Minchin and some other great artists on the bill.