Armour Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaponry & Armor

Weaponry & Armor “Imagine walking five hundred miles over the course of two weeks, carrying an arquebus, a bardiche, a stone of grain, another stone of water, ten pounds of shot, your own armor, your tent, whatever amenities you want for yourself, and your lord’s favorite dog. In the rain. In winter. With dysentery. Alright, are you imagining that? Now imagine that as soon as you’re done with that, you need to actually fight the enemy. You have a horse, but a Senator’s nephew is riding it. You’re knee-deep in mud, and you’ve just been assigned a rookie to train. He speaks four languages, none of which are yours, and has something to prove. Now he’s drunk and arguing with your superiors, you haven’t slept in thirty hours, you’ve just discovered that the fop has broken your horse’s leg in a gopher hole, and your gun’s wheellock is broken, when just then out of the dark comes the beating of war-drums. Someone screams, and a cannonball lands in your cooking fire, where you were drying your boots. “Welcome to war. Enjoy your stay.” -Mago Straddock Dacian Volkodav You’re probably going to see a lot of combat in Song of Swords, and you’re going to want to be ready for it. This section includes everything you need to know about weapons, armor, and the cost of carrying them to battle. That includes fatigue and encumbrance. When you kit up, remember that you don’t have to wear all of your armor all of the time, nor do you need to carry everything physically on your person. -

![Educational Charts. [Arms and Armor]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4584/educational-charts-arms-and-armor-264584.webp)

Educational Charts. [Arms and Armor]

u UC-NRLF 800 *B ST 1S1 CO CO Q n . OPOIIT, OF ART EDUCATIONAL G E A H I S Table of Contents: 1 Periods, of armor, 2 Suit of armor: pts. named. Evolution of 3 Helmets. 4 Breastplates. 5 Gauntlets. 6 Shields. 7 Swords. 8 Pole Arms. 9 Guns,. 10 Crossbows. 11 Spurs. 12 Photos s h ov; i ?: how a helmet is ma d e ft 4- HALF ARMOR COMPLETE ARMOR LATE XVI CENTURY COMPLETE ARMOR XVI CENTURY MAXIMILIAN TRANSITIONAL MAIL AND PLATE EUROPEAN ARMOR AND ITS DEVELOPMENT DURING A THOUSAND YEARS FROM A.D. 650 TO 165O 650 MASHIKE MURAYAMft.DCI.. 366451 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/educationalchartOOmetrrich S u BOWL or SKULL, timbre, scheitelstuck, COPPO, CALVA JUGULAR. JUCULAIRE. BACKENSTUCK. JUGULARE. YUGULAR VENTAIL, VENTAIL. SCHEMBART, VENTACL10 VENTALLE. [UPPER PART BECOMES VISOR] BEVOR, MENTONNIERE, KINREFF, BAVIERA, BARBOTE RONDEL, RONDELLE. SCHEIBE, ROTELLINO, LUNETA GORGET. GORGERIN, KRAGEN, GOLETTA, GORJAL NECK-GUARD garde-col, brech- RANDER, GUARDA-GOLETTA, BUFETA . PAULDRON, EPAULIERE, ACHSEL. I SPALL ACCIO, GUARDABRAZO / _ 11^4 LANCE -REST, faucre. rust- HAKEN, RESTA, RESTA DE MUELLE REREBRACE, arrie re- bras. OBERARMZEUG, BRACCIALE. BRAZAL BREASTPLATE, plas- tron. BRUST, PETTO, PETO /o^ - ELBOW-COP. CUBIT1ERE. ARMKACHEL. CUBITIERA, CODAL '' BACKPLATE. dossi- ERE. RUCKEN, SCHIENA, DOS VAMBRACE. avant- BRAS. UNTERARMROHR, BRACCIALE, BRAZAL GAUNTLET, gantelet, hand- SCHUH, GANTLET, MANOPLA LOIN-GUARD GARDE- ' REINS. GESASSREIFEN, FALDA FALDAR 'TACES BRACCONIERE, BAUCH- REIFEN. PANZIERA. FALDAR TASSET. TASSETTE, BEINTASCHEN, FIANCALE. ESCARCELA - ' FALD. BRAYETTE. STAHLMACHENUN TERSHUTZ. BRAGHETTA. BRAGADURA CUISHE. CUISSARD, DIECHLINGE, COS- CIALE, OUIJOTES KNEE-COP. -

Tournament Gallery - Word Search

HERALDRY Heraldry involves using patterns pictures and colours to represent a knight. Below is an example. Q: Why do you think heraldry was important to a knight? TOURNAMENT Design and GALLERY sketch your own coat of arms KEY STAGE 3 Self-Guided Visit Student Activity Handbook w w w w w w . r r o o Name: y y a a l l a a r r School: m m o o u u r r i i Class: e e s s . o o r r g g Date: © Royal Armouries The Tournament Gallery can be found on Floors 2 and 3 of the Museum. TUDOR TOURNAMENT ARMOUR DECORATION Q: In the Tudor period the tournament was highly popular. Name and describe Find the section in the gallery that describes different ways to the different games associated with the tournament? decorate armour. Q: Name the methods used to decorate these armours A B C D E Q: Why do you think knights and nobles decorated their armour? Q: Find a piece of decorated armour in the gallery sketch it in the box below and describe why you chose it. Armours were made to protect a knight in battle or in the tournament. Q: What are the main differences between armour made to wear in battle and tournament armour? 1 © Royal Armouries © Royal Armouries 2 FIELD OF CLOTH OF GOLD KING HENRY VIII Find the painting depicting the Field of Cloth of Gold tournament. Henry VIII had some of the most impressive armours of his time. To the right of the painting of the Field of Cloth of Gold is a case displaying an armour made for Henry VIII; it was considered to be one of Q: In which year did the Field of Cloth of Gold tournament take place? the greatest armours ever made, why do you think this was? Q: On the other side of the painting is an usual armour. -

World Warrior

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 4-6-2014 World Warrior Dan Farruggia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Farruggia, Dan, "World Warrior" (2014). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. world warrior dan farruggia a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of all the requrements for the degree of masters of fine arts in visual communication design school of design college of imaging arts and sciences rochester institute of technology rochester, ny april 6, 2014 acknowledgements Without the support of the following people, none of this would have been possible. committee members Chris Jackson, Shaun Foster, and David Halbstein. family and friends I could not have done this without the overwhelming support of my friends and family. They have shown so much support to me and my career over the years. One final acknowledgement to my mother and father, who have shown me the most support and faith more then words can express. Thank you! committee approval Chief Thesis Adviser:Chris Jackson, Visual Communication Design Signature of Chief Thesis Adviser Date Associate Thesis Adviser:Shaun Foster, Visual Communication Design Signature of Associate Thesis Adviser Date Associate Thesis Adviser:David Halbstein, Visual -

TOTAL Headborne System Solutions GROUND PRODUCT CATALOG

TOTAL Headborne System Solutions GROUND PRODUCT CATALOG www.gentexcorp.com/ground USA Coast Guardsmen fast-rope from an Air Force UH-60G Pave Hawk helicopter during a training exercise at Air Station Kodiak, Alaska, Feb. 22, 2019. Photo By: Coast Guard Chief Petty Officer Charly Hengen Gentex Corporation takes pride in our dedication to the mission of providing optimal protection and situational awareness to global defense forces, emergency responders, and industrial personnel operating IT’S GO TIME in high-performance environments. 2 For complete product details, go to gentexcorp.com/ground 3 OUR PROUD HISTORY OUR PEERLESS QUALITY Gentex has been at the forefront of innovation for over 125 years, from product development to Gentex Corporation ensures that our Quality Management Systems consistently provide products quality enhancement and performance. Our philosophy of continually reinvesting in our employees, to meet our customers’ requirements and enables process measurements to support continuous our customers, and our capabilities and technologies shows in the growth of our business and the improvements. We comply with an ISO 9001 certified Quality Management System that is supplemented game-changing innovations our people have created. with additional quality system requirements that meet the AS9100D standard, a standard that provides strict requirements established for the aviation, space, and defense industries. 4 For complete product details, go to gentexcorp.com/ground 5 ENGINEERED & TESTED MISSION CONFIGURABLE Whether it’s a helmet system, a respiratory protection system, leading-edge optics, or a communication headset, Gentex It’s all about Open Architecture. Our approach to product integration results in systems with components that work together Corporation takes the same all-in approach to product design and engineering. -

Ffib COSTUME of the Conquistadorss 1492-1550 Iss

The costume of the conquistadors, 1492-1550 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Coon, Robin Jacquelyn, 1932- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 08/10/2021 16:02:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/348400 ffiB COSTUME OF THE CONQUISTADORSs 1492-1550 iss ' ' " Oy _ , ' . ' Robin Goon A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPiRTMENT OF DRAMA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of ■ MASTER OF ARTS v ' . In the Graduate College THE UHIFERSITI OF ARIZONA 1962 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to bor rowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. " / /? signed i i i Q-'l ^ > i / r ^ t. -

The Handbook of Hazards and House Rules and Legendary Quest Are Trademarks of Loreweaver Games

Official Game Rules of Legendary Quest™ by John Kirk and Mark Chester The Handbook of Hazards and House Rules and Legendary Quest are trademarks of LoreWeaver Games. he Handbook of Hazards and House Rulesä is Copyright ã1996-2004 by LoreWeaver. All rights reserved. You may make unlimited electronic copies of this book and may print out individual copies for your own personal use; provided the work is copied in its entirety and you make no alterations to its content. You may T make limited numbers of hard copies at a printing service (no more than 5 copies at a time), provided said printing service does not otherwise act as a publishing house and provided said printing service charges fees for the copies that are commensurate with its general copying services. You may be reimbursed by the recipients of those copies for the copy fees, but may not otherwise charge those recipients any amount over this cost. In other words, if you try to sell this book for profit, we’ll sue the pants off of you. On the other hand, if you are a publishing house that wants to sell this book for profit, get a hold of us and we’ll talk turkey. (Note: If you’re one of those “publishing houses” that charges its writers for the privilege of having you publish their books, don’t even bother asking. Real publishers pay writers, not the other way around.) All characters are fictional; any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental. LoreWeaver intends to protect its interests in this game to the full extent of the law. -

The Classic Suit of Armor

Project Number: JLS 0048 The Classic Suit of Armor An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by _________________ Justin Mattern _________________ Gregory Labonte _________________ Christopher Parker _________________ William Aust _________________ Katrina Van de Berg Date: March 3, 2005 Approved By: ______________________ Jeffery L. Forgeng, Advisor 1 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................. 5 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 6 RESEARCH ON ARMOR: ......................................................................................................................... 9 ARMOR MANUFACTURING ......................................................................................................................... 9 Armor and the Context of Production ................................................................................................... 9 Metallurgy ........................................................................................................................................... 12 Shaping Techniques ............................................................................................................................ 15 Armor Decoration -

The Steel Pot History Design

The Steel Pot The M1 helmet is a combat helmet that was used by the United States military from World War II until 1985, when it was succeeded by the PASGT helmet. For over forty years, the M1 was standard issue for the U.S. military. The M1 helmet has become an icon of the American military, with its design inspiring other militaries around the world. The M1 helmet is extremely popular with militaria collectors, and helmets from the World War II period are generally more valuable than later models. Both World War II and Vietnam era helmets are becoming harder to find. Those with (original) rare or unusual markings or some kind of documented history tend to be more expensive. This is particularly true of paratroopers' helmets, which are variants known as the M1C Helmet and M2 Helmet. History The M1 helmet was adopted in 1941 to replace the outdated M1917 A1 "Kelly" helmet. Over 22 million U.S. M-1 steel helmets were manufactured by September 1945 at the end of World War II. A second US production run of approximately one million helmets was made in 1966–1967. These Vietnam War–era helmets were different from the World War II/Korean War version by having an improved chinstrap, and were painted a light olive green. The M1 was phased out during the 1980s in favor of the PASGT helmet, which offered increased ergonomics and ballistic protection. It should be noted that no distinction in nomenclature existed between wartime front seams and post war shells in the United States Army supply system, hence World War II shells remained in use until the M1 was retired from service. -

Codex Martialis: Weapons of the Ancient World

Cod ex Mart ial is Weapo ns o f t he An cie nt Wor ld : Par t 2 Arm or a nd M issile Weapo ns Codex Martialis : Weapons of the A ncient World Par t II : Ar mo r an d Mi ss il e We ap on s 1 188.6.65.233 Cod ex Mart ial is Weapo ns o f t he An cie nt Wor ld : Par t 2 Arm or a nd M issile Weapo ns Codex Martialis: Weapons of the Ancient World Part 2 , Ar mor an d Missile Weapo ns Versi on 1 .6 4 Codex Ma rtia lis Copyr ig ht 2 00 8, 2 0 09 , 20 1 0, 2 01 1, 20 1 2,20 13 J ean He nri Cha nd ler 0Credits Codex Ma rtia lis W eapons of th e An ci ent Wo rld : Jean He nri Chandler Art ists: Jean He nri Cha nd ler , Reyna rd R ochon , Ram on Esteve z Proofr ead ers: Mi chael Cur l Special Thanks to: Fabri ce C og not of De Tail le et d 'Esto c for ad vice , suppor t and sporad ic fa ct-che cki ng Ian P lum b for h osting th e Co de x Martia lis we bsite an d co n tinu in g to prov id e a dvice an d suppo rt wit ho ut which I nev e r w oul d have publish ed anyt hi ng i ndepe nd ent ly. -

Combat Helmets

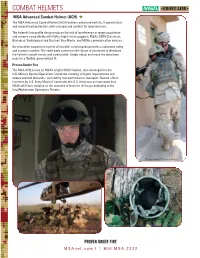

COMBAT HELMETS MSA Advanced Combat Helmet (ACH) ★ The MSA Advanced Combat Helmet (ACH) delivers advanced ballistic, fragmentation, and impact head protection, with unsurpassed comfort for long-term use. The helmet’s low-profile design reduces the risk of interference in target acquisition and ensures compatibility with NVGs (night-vision goggles), MSA’s CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear) Gas Masks, and MSA’s communication devices. An innovative suspension system of movable comfort pads provides customized sizing and superior comfort. The sized pads conform to the shape of your head to distribute the helmet’s weight evenly and comfortable. Simply adjust and move the absorbent pads for a flexible, personalized fit. Proven Under Fire The MSA ACH, based on MSA’s original MICH helmet, was developed for the U.S. Military Special Operations Command, meeting stringent requirements and unprecedented demands , and setting new performance standards. Named a Best Invention by U.S. Army Materiel Command, the U.S. Army was so impressed that MSA’s ACH was adopted as the standard of issue for all troops deploying to the Iraq/Afghanistan Operations Theatre. Department of Defense photo Department of Defense photo PROVEN UNDER FIRE MSAnet.com | 1.800.MSA.2222 4 COMBAT HELMETS Sizing Specifications— ACH - TC 2000 - MICH Series Shell Size Pad Size Head Size (U.S.) 1 Medium No. 8 (1”) 6 ⁄2 – 7 Components 3 1 • Ballistic-resistant Kevlar® shell Medium No. 6 ( ⁄4”) 7 – 7 ⁄4 • Four-point adjustable chinstrap 1 1 Large No. 8 (1”) 7 ⁄4 – 7 ⁄2 retention system 3 1 3 • Seven-pad adjustable suspension system Large No. -

Qarmor Available in the Known World

Playing the Game: Combat ARMOR AVAILABLE IN THEQ KNOWN WORLD The Armor on this list (a partial list, at that) is described by the ‘suit,’ in effect a complete outfit that is usually calledharness a . Armor is not that different from clothing (and indeed clothing is included on this list), in the sense that it not only has a function to protect the wearer but also reflects the style and fashions of the material Culture in which the wearer lives. It’s also simpler to describe armor as a suit or harness rather than having you buy and track each individual piece of armor that you are wearing, which can get very complicated with as many Hit Locations as there are in Artesia AKW. There is, however, a short list of individual pieces with which you can customize the harnesses listed here. The listings include a description of the outfit, its base weight, the protective value of the outfit, and its cost. Armor Type is listed in cases where the armor shapes damage; this is Mail, Scale, or Plate, and refers to the predominant armor type used. Guides should use discretion in applying Armor Type to individual hit locations; some common sense can be applied (a warrior wearing leather gloves should receive a leather Armor Type benefit when hit in the hands, regardless of the armor worn). The protective value is listed as Cut/Puncture/Impact protection. Each harness has an Overall Protective Value, but may also have Exposed body parts (with no protection), Weak Points, and Strong Points. The armor listed here is pre-manufactured munition armor – bought off the rack, so to speak.