The City and the Country in the 1920S: Collected Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA Departamento De-Língua E Literatura Estrangeiras SINCLAIR! LEWIS: the NOBLE BARBARIAN A

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA Departamento de-Língua e Literatura Estrangeiras SINCLAIR! LEWIS: THE NOBLE BARBARIAN A Study of the Conflict of European and American Values in the Life and Fiction of Sinclair Lewis Tese submetida à Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para a i obtençãoí do grau de Mestre em Letras Hein Leonard Bowles Novembro - 1978 Esta Tese foi julgada adequada para a obtenção do título de MESTRE EM LETRAS Especialidade Língua Inglesa e Literatura Correspondente e aprovada em sua forma final pelo Programa de PÓs-Graduação Pro John Bruce Derrick, PhD Orientador Z&L- Prof. Hilário^hacio Bohn, PhD Integrador do Curso Apresentada perante a Comissão Examinadora composta do; professores: Prof. John Bruce Derrick, PhD Para Dirce, Guilherme e Simone Agradecimentos À Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina À Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa À Fundação Faculdade Estadual de Filosofi de Guarapuava Ao Prof. Dr. John B. Derrick Ao Prof. Dr. Arnold Gordenstein ABSTRACT In Sauk Centre, a fairly new and raw midwestern American town in the first years of our century, a solitary youth reads Kipling, Scott, Tennyson and Dickens and becomes enchanted with Europe: its history, traditions and people. Seeing the monotonous and endless extensions of prairie land, the rustic farmer cottages and the haphazard design of his hometown, he imagines the superior graces of. a variegated European landscape; historical cities, old structures, castles and mansions that hint of aristocratic generations. And his people, engaged in the routine of their daily activities; their settled forms of behavior, conversation and clothing, become ; quite uninspiring for him as contrasted to his idealization of a romantic, exotic and stirring European world wherein cultured gentlemen and gracious ladies abound. -

Sinclair Lewis Society Newsletter VOLUME TWENTY, NUMBER ONE FALL 2011

The SINCLAIR LEWIS SOCIETY NEWSLETTER VOLUME TWENTY, NUMBER ONE FALL 2011 LANCELOT TODD: A CASE FOR FICTIONAL INDEPENDENCE Samuel J. Rogal Illinois Valley Community College In a neat package of a single paragraph containing a summarization of Lewis’s Lancelot Todd, Mark Schorer de- termined that Lewis’s pre-1920s version of the present-day public relations agent run wild represented a relatively simple “ANOTHER PERFECT DAY”: WEATHER, instrument of his creator’s satire and farce. Schorer labeled MOOD, AND LANDSCAPE IN SINCLAIR Todd “a suave immoralist” and “swindler” who threads his LEWIS’S MINNESOTA DIARY way through a series of short stories with plots that hold no “real interest” and whose principal fictional function focuses Frederick Betz upon Lewis’s preparations for the larger worlds of George Southern Illinois University–Carbondale Babbitt and Elmer Gantry (Schorer 239). Although few critical commentators of twenty-first-century American fiction seem- Sinclair Lewis’s Minnesota Diary, 1942–46, superbly ingly have possessed the stamina or willingness to challenge introduced and edited by George Killough, “offers an inside Schorer’s generalized characterization of Todd, there lies suf- view of a very public person,” a “strangely quiet and factual” ficient evidence in the stories themselves to allow for at least diarist, who “keeps meticulous notes on weather, writes ap- a defense of Todd as a character who might somehow stand preciative descriptions of scenery, mentions hundreds of people independent of the likes of Babbitt and Gantry. he is meeting, and chronicles exploratory trips around Min- Lancelot Todd appears in seven Lewis stories published nesota” (15). -

GUARDIANS of AMERICAN LETTERS Roster As of February 2021

GUARDIANS OF AMERICAN LETTERS roster as of February 2021 An Anonymous Gift in honor of those who have been inspired by the impassioned writings of James Baldwin James Baldwin: Collected Essays In honor of Daniel Aaron Ralph Waldo Emerson: Collected Poems & Translations Charles Ackerman Richard Wright: Early Novels Arthur F. and Alice E. Adams Foundation Reporting World War II, Part II, in memory of Pfc. Paul Cauley Clark, U.S.M.C. The Civil War: The Third Year Told By Those Who Lived It, in memory of William B. Warren J. Aron Charitable Foundation Richard Henry Dana, Jr.: Two Years Before the Mast & Other Voyages, in memory of Jack Aron Reporting Vietnam: American Journalism 1959–1975, Parts I & II, in honor of the men and women who served in the War in Vietnam Vincent Astor Foundation, in honor of Brooke Astor Henry Adams: Novels: Mont Saint Michel, The Education Matthew Bacho H. P. Lovecraft: Tales Bay Foundation and Paul Foundation, in memory of Daniel A. Demarest Henry James: Novels 1881–1886 Frederick and Candace Beinecke Edgar Allan Poe: Poetry & Tales Edgar Allan Poe: Essays & Reviews Frank A. Bennack Jr. and Mary Lake Polan James Baldwin: Early Novels & Stories The Berkley Family Foundation American Speeches: Political Oratory from the Revolution to the Civil War American Speeches: Political Oratory from Abraham Lincoln to Bill Clinton The Civil War: The First Year Told By Those Who Lived It The Civil War: The Second Year Told By Those Who Lived It The Civil War: The Final Year Told By Those Who Lived It Ralph Waldo Emerson: Selected -

SINCLAIR LEWIS' Fiction

MR, FLANAGAN, who is professoT of American literature in. the University of Illinois, here brings to a total of fifteen his mafor contributions to this magazine. The article's appearance appropriately coincides with the seventy-fifth anniversary of Lewis' birth and the fortieth of the publication of Main Street. The MINNESOTA Backgrounds of SINCLAIR LEWIS' Fiction JOHN T. FLANAGAN SINCLAIR. LEWIS 'was once questioned his picture of Gopher Prairie and Minne about the autobiographical elements in sota and the entire Middle W^est became Main Street by a friend 'whose apartment both durable and to a large extent accurate. he 'was temporarily sharing. The novelist A satirist is of course prone to exaggeration. remarked to Charles Breasted that Dr. 'Will Over-emphasis and distortion are his stock Kennicott, the appealing country physician in trade. But despite this tilting of the in his first best seller, 'was a portrait of his balance, his understanding of places and father; and he admitted that Carol, the doc events and people must be reliable, other tor's 'wife, 'was in many respects indistin wise he risks losing touch with reality com guishable from himself. Both "Red" Lewis pletely, Lewis was born in Minnesota, he and Carol Kennicott were always groping spent the first seventeen years of his life in for something beyond attainment, always the state, and he returned on frequent visits, dissatisfied, always restless, and although which sometimes involved extensive stays both were frequently scornful of their im in Minneapolis, St, Paul, or Duluth, A num mediate surroundings they nevertheless ber of his early short stories and six of his lacked any clear vision of what could or twenty-two novels are localized wholly or should be done. -

Sinclair Lewis: Social Satirist

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Master's Theses Graduate School Spring 1951 Sinclair Lewis: Social Satirist Milldred L. Bryant-Parsons Fort Hays Kansas State College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bryant-Parsons, Milldred L., "Sinclair Lewis: Social Satirist" (1951). Master's Theses. 468. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses/468 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. SINCLAIR LEWIS: SOCIAL SAT I RI ST being A thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Fort Hays Kansas State College in partial fulfillment of the r equirements f or the De gree of Master of Scien ce by ' \, Mrs . Mildred L. Bryant_!arsons , A. B. Kansas We sleyan University Date ~ /ff/f'J{ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express her sincere appreciation to Dr. Ralph V. Coder, under whose direction this thesis was prepared, for his eneour- agement and constructive criticism. Dr. F. B. Streeter has been very helpful in showing the mechanics of thesis writing. Miss Roberta Stout has ' offered many excellent suggestions. The writer also wishes to thank the library staff: Mrs. Pauline Lindner, Miss Helen Mcilrath, and Mrs. Nina McIntosh who have helped in gathering materials. c-1> TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE INTRODUCTION I • SATIRE ON PSEUDO-CULTURE Mains treet. • • 6 Dodsworth •• . 12 The Prodigal Parents .• 13 II. SATIRE ON RACE PREJUDICE Mantrap • • • • • 15 Kingsblood Royal . -

Sinclair Lewis

SATIRE OF CHARACTERIZATION IN THE FICTION OF SINCLAIR LEWIS by SUE SIMPSON PARK, B.A. , M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Technological College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairman of the Committee &l^ 1? }n^ci./A^.Q^ Accepted <^ Dean of the Gradu^e SiChool May, 196( (\^ '.-O'p go I 9U I am deeply indebted to Professor Everett A. Gillis for his direction of this dissertation and to the other members of my committee, Professors J. T. McCullen, Jr., and William E. Oden, for their helpful criticism. I would like to express my gratitude, too, to my husband and my daughter, without whose help and encouragement this work would never have been completed. LL CONTENTS I. SINCLAIR LEWIS AND DRAMATIC SATIRE 1 II. THE WORLD OF THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY 33 III. THE PHYSICIAN AND HIS TASK 68 IV. THE ARTIST IN THE AMERICAN MILIEU 99 V. THE DOMESTIC SCENE: WIVES AND MARRIAGE ... 117 VI. THE AMERICAN PRIEST 152 NOTES ^76 BIBLIOGRAPHY 131 ILL CHAPTER I SINCLAIR LEWIS AND DRAMATIC SATIRE In 1930 Sinclair Lewis was probably the most famous American novelist of the time; and that fame without doubt rested, as much as on anything else, on the devastating satire of the American scene contained in his fictional portrayal of the inhabitants of the Gopher Prairies and the Zeniths of the United States. As a satirist, Lewis perhaps ranks with the best--somewhere not far below the great masters of satire, such as Swift and Voltaire. -

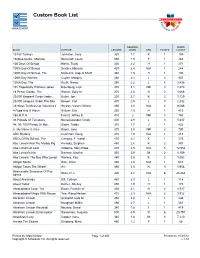

Custom Book List

Custom Book List MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT 10 Fat Turkeys Johnston, Tony 320 1.7 K 1 159 10-Step Guide...Monster Numeroff, Laura 450 1.5 F 1 263 100 Days Of School Harris, Trudy 320 2.2 H 1 271 100th Day Of School Schiller, Melissa 420 2.4 N/A 1 248 100th Day Of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 340 1.5 H 1 190 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 360 2.1 L 2 937 100th Day, The Krulik, Nancy 350 2.2 L 4 3,436 101 Hopelessly Hilarious Jokes Eisenberg, Lisa 370 3.1 NR 3 1,873 18 Penny Goose, The Walker, Sally M. 370 2.8 N 2 1,066 20,000 Baseball Cards Under... Buller, Jon 330 2.7 K 2 1,129 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea Bowen, Carl 470 2.5 L 3 2,232 23 Ways To Mess Up Valentine's Wesley, Valerie Wilson 490 2.6 N/A 4 8,085 4 Pups And A Worm Seltzer, Eric 350 1.5 H 1 413 763 M.P.H. Fuerst, Jeffrey B. 410 2 NR 3 760 88 Pounds Of Tomatoes Neuschwander, Cindy 400 2.9 L 3 1,687 98, 99, 100! Ready Or Not... Slater, Teddy 310 1.7 J 1 432 A. My Name Is Alice Bayer, Jane 370 2.4 NR 2 700 ABC Mystery Cushman, Doug 410 1.9 N/A 1 218 ABCs Of My School, The Campoy, F. Isabel 430 2.2 K 1 275 Abe Lincoln And The Muddy Pig Krensky, Stephen 480 2.6 K 2 987 Abe Lincoln At Last! Osborne, Mary Pope 470 2.5 N/A 5 12,553 Abe Lincoln's Hat Brenner, Martha 330 2.9 M 2 1,159 Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved Winters, Kay 480 3.5 K 2 1,052 Abigail Spells Alter, Anna 480 2.6 N/A 1 610 Abigail Takes The Wheel Avi 390 3.5 N 3 1,958 Abominable Snowman Of Pas- Stine, R. -

ANALYSIS Main Street

ANALYSIS Main Street (1920) Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951) “My dear Mr. Sinclair Lewis-- I am writing to tell you how glad I am that you wrote Main Street. Hope it will be read in every town in America. As a matter of fact I suppose it will find most of its readers in the cities. You’ve sure done a job. Very Truly yours,” Sherwood Anderson Letter to Lewis (1 December 1920) “[Main Street produces] a sense of unity and depth by reflecting Main Street in the consciousness of a woman who suffered from it because she had points of comparison, and was detached enough to situate it in the universe.” Edith Wharton Letter to Lewis (1922) “In Main Street he set out to tell a true story about the American village, whether anybody would read it or not, and he was surprised by the tremendous acclamation. He had not reasoned that it was time to take a new attitude toward the village or calculated that it would be prudent. He only put down, dramatically, the discontents that had been stirring in him for at least fifteen years. But there was something seismographic in his nerves, and he had recorded a ground swell of popular thinking and feeling. His occasional explicit comments on dull villages were quoted till they reverberated. Many readers thought there were more such comments than there were. The novelty was less in the arguments of the book than in the story. That violated a pattern which had been long accepted in American fiction. The heroes of Booth Tarkington, for instance, after a brief rebellion of one kind or other, came to their senses and agreed with their wiser elders. -

ANALYSIS Dodsworth

ANALYSIS Dodsworth (1929) Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951) “In Dodsworth (1929) Lewis was only incidentally satirical. Here more profoundly than in any of his novels he studied the ins and outs of a heart through a crucial chapter of a human life. Dodsworth is a Zenith magnate who retires from business. ‘He would certainly (so the observer assumed) produce excellent motor cars; but he would never love passionately, lose tragically, nor sit in contented idleness upon tropic shores.’ His story begins as if he were to be another Innocent Abroad, an American taking his humorous ease in Europe. Though Dodsworth values his own country, and often defends it against any kind of censure, he is no brash frontiersman like the Innocents of Mark Twain. That older kind of traveler had passed with the provincial republic of the mid-nineteenth century. But Dodsworth’s travels are complicated by his wife, a pampered women desperately holding on to her youth, fascinated by what seem to her the superior graces of European society, and susceptible to its men. In her bitter discontent she becomes a poisonous shrew, then deserts her husband for a lover. Long in love with her, Dodsworth cannot break off either his affection or his sense of responsibility. She is in his blood. The history of his recovery is like a convalescence of a spirit, and it is told with feeling and insight. Externally, Dodsworth is the essence of modern America on its grand tour, neither cocksure like Mark Twain’s travelers in Europe, nor quivering and colonial like Henry James’s. -

Sinclair Lewis Almanac

Sinclair Lewis Almanac January 2, 1942 On this day in history, critically acclaimed American novelist Sinclair Lewis divorced his second wife Dorothy Thompson. Their marriage became the basis of the Broadway production Strangers, which opened in 1979 after both of their deaths. Initially wed on the grounds of love, their marriage became a struggle with the strain of both of their prolific literary accomplishments and constant travel. In 1930 they had a son, Michael Lewis, who remained, along with their Vermont residence, Twin Farms, in Thompson’s custody after the divorce. The court ordered Lewis not to remarry within the next two years; Lewis immersed himself into his newfound freedom. 10, 1951 On this day in history, Nobel Prize-winning American author Sinclair Lewis died in a clinic on the outskirts of Rome of a heart attack. Bedridden at the Clinica Electra on Monte Mario since December 31, his doctor initially diagnosed Lewis with acute delirium tremens. However temporary the initial attacks were, any fully coherent moments before he was taken by ambulance to the clinic were his last. Lewis had his final heart attack on the 9th and died watching the sun rise the next day. Based upon his wishes, Lewis’s body was cremated and buried in his place of birth, Sauk Centre, Minnesota. 19, 1951 Sinclair Lewis’s ashes are buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Sauk Centre, Minnesota. His brother Claude is present; his former wife, Dorothy Thompson, is not, although she visits Sauk Centre in 1960 for a celebration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of his birth. -

Helen Marjorie Norman, B. A

3 1 t 9 SATIRE ON AMERICAN LIFE AS PORTRAYED I TItE NOVELS OF SINCIAIR LETIS THESIS p resented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State Teachers College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTERR OF ARTS By Helen Marjorie Norman, B. A. Blum, Texas August, 1940 k8837t TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . f- . - - . .- . Criticisms of Lewis's Novels as a Whole Criticism of the Individual Novels II. SATIRECTLIFE IN SMALL A TOE . , . , 17 Summary of Main Street A DescriptionofSmall Towns The Citizens The Educational Facilities Economic Conditions Social Background Religious Background The Discontent of the People III. SATIRE ON THE LIFE OF A BUIST TI AN *f . 34 The Business Man's Lack of Integrity The Hypocrisy of the Business Man Educational Background Social Background Political Background Religious Background Summary of Babbitt, Mantrap, Dodsworth and Work of A rt IV. CRITICISM OF TIT MEDICAL PROFESSION . 60 Summary of Arrowsmith Professors of Medica Institutions Fraternities of Medical Schools Students of Medical Universities Commercialism of Medical Institutions Trials of an Honest Physician V. SATIRE ON CERTAIN PHASES OF RELIGION . .76 Faults of the Church and Sunday School The Modern Gospel Social-service Organizations 111 " - ,. ._ T__,-'M .. ..... u v7. ... .. ,+. dt 7;e4y8t6b «k r. s _wr- w ,- : 6:n=N- _ _.... Chapter Impostures in the Church Hypocrisy of Evangelists Insincerity of the Ministers Differences of Religious Sects Summary of Elmer Gant VI. CRITICISM OF POLITICS, GOVERNMENT, AND SOCIAL REFOR1T . , . * * . * * . , * , * * 93 Summary of The Man Who Knew CoolieAnn Vickers, It Can'tTappen Here, and TET Lr2tgal Parer Ignorance ofPoliticians Ignorance of People Who Vote Faults in the Democratic Government Criticism of the president Criticism of the courts Unions and organized labor Failure of Social Organizations Deplorable conditions of society Deplorable conditions of prisons Capital punishment Hardships of the social workers VII. -

THE IMAGES of WOMEN in the NOVELS of SINCLAIR LEWIS By

THE IMAGES OF WOMEN IN THE NOVELS OF SINCLAIR LEWIS By ALICE LOUISE SODOWSKY II Bachelor of Arts University of Iowa Iowa City, Iowa 1952 Master of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1970 Submitted to the Faculty cf the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 1977 lhe<:,.,s \911D Slo \C\ .\_, CQ\:)· J._ THE IMAGES OF WOMEN IN THE NOVELS OF SINCLAIR LEWIS Thesis Approved: ' ~Ch"Dean of the ~----- Graduate College 997114 ii PREFACE A few years ago I read, by chance, Sinclair.Lewis's novel Ann Vickers, published in 1933, and I was surprised to find in its story the concepts and rhetoric of a feminist movement as contemporary as the cur rent ideas and expressions being espoused by the various women's libera tion and rights groups. The question of women 1 s roles occurred to me: are women's roles today different from those in the earlier part of the century? What are the changes, if any, in their roles in fiction? I was particularly interested in Lewis's fiction because he was from the Midwest, wrote about middle-class people, and remains a severe critic of our towns and cities a.s well as of our social institutions and values. A study directed towards examining the images of women in his novels, which cover a period of about thirty-seven years of our history, would, I thought, not only shed light on who the midwestern woman is, but also on who we'are all becoming.